Contents

Header image above: Coils of unused concertina wire sit on the borderline at the top of the Paso del Norte bridge between El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

WOLA staff paid a field research visit to the U.S.-Mexico border cities of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez during the second week of December 2019. This memo explains what we learned in a part of the border that underwent an extremely difficult year.

It covers the reasons for a very sharp rise and fall in child and family migration, which peaked in May. It reviews the Trump administration’s implementation of “Remain in Mexico,” “Metering,” “Safe Third Country” agreements, and other measures that, taken together, all but eliminate the right to seek asylum in the United States by approaching the U.S.-Mexico border. It discusses other rights issues like the threats migrants face while waiting in Juárez, miserable asylum processing conditions, deaths while attempting to avoid apprehension, and use of force. It provides an update on border wall construction in this sector, and on the worsening security situation in Ciudad Juárez. Finally, this memo concludes with a note of praise and concern for these cities’ under-appreciated community of advocates and service providers. These are people bearing a heavy burden, and many are traumatized by the human suffering they witness, the bottomless need for their work, and the mounting obstacles they must overcome to do it.

Child and family migration from Central America has been increasing steadily since 2012. The factors driving it—insecurity and violence, lack of opportunity, climate change, desire for family re-unification—are as strong now as they were then. Smugglers and others who benefit from the status quo of migration aren’t going out of business. It’s ludicrous to expect long-lasting results from heavy-handed measures, like those that the Trump administration is now pursuing, that emphasize punishment while leaving the causes in place.

We wrote this in a hurry, posting it within five days of our return from the border, with the goal of getting our findings out before the end-of-year holidays. This memo has thus undergone a less thorough editing process than usual. It may contain minor errors, and we will add revisions as necessary.

U.S. authorities divide the U.S.-Mexico border into nine sectors. Three years ago, WOLA visited the “El Paso Sector,” which comprises the westernmost 88 miles of the Texas-Mexico border and all of the 180-mile New Mexico-Mexico border, including the large cities of El Paso, Texas (population 680,000) and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua (1,500,000).

We went there because, at the time, it seemed like the most “typical” border region. Whether measuring migration, drug seizures, violence, or human rights abuses, El Paso ranked in the middle of the nine sectors.

After visiting, we’d concluded that the area was witnessing a growing humanitarian crisis, but not a security crisis. Today, national security threats are still scarce. But we found during a December 11-13, 2019 return to El Paso and Ciudad Juárez that the humanitarian crisis has multiplied.

And now, El Paso is no longer “typical.” Far from it: in 2019 it became the border’s number-two sector for arrivals of migrants; it had been number five in 2016. In 2019, Border Patrol apprehended 182,143 migrants in the El Paso sector, 82 percent of them (149,068) children or parents, mostly from Central America. That was a 577 percent increase over 2018, and a 627 percent increase in children and families.

At its height during the spring of 2019, the migrant wave involved hundreds of parents and children arriving together in batches, often in remote desert areas of New Mexico’s western “Bootheel” region, like the tiny border-crossing town of Antelope Wells.

Since a 1997 court settlement prohibits long-term detention of children, most families received dates to appear in immigration court for their asylum claims, and were then released into El Paso. There, most spent a short time in a charity-run respite center, Annunciation House, which gave them meals, clothing, a place to stay, and contacts with relatives for travel to elsewhere in the United States. At the height of the migrant wave, Annunciation House was taking in several hundred people per day—CBP and ICE dropped off 1,050 on the heaviest day—and spending about US$100,000 per month to put migrants in local hotels.

Acronyms

In an interview, Border Patrol agents said that by mid-year the sector’s El Paso Station had only two or three agents available to patrol the entire 11 miles of border that are the station’s responsibility. The rest were filling out intake forms, taking people to hospitals, or managing holding spaces filled with children—though these cells had been designed to hold what until recently was the typical migrant population: single men.

While most migrants came from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, they represented well over a dozen countries. A growing number of Cubans and Brazilians arrived in Ciudad Juárez and El Paso and, later in the year, the number of asylum-seekers from elsewhere in Mexico began to grow. In fiscal 2019, according to Border Patrol figures obtained by El Paso’s Border Network for Human Rights, the most frequently apprehended migrants in the sector were “Guatemalans (79k), Hondurans (42k), Brazilians (16k), Salvadorans (15k), Mexicans (15k), and Cubans (12k).”

And then, starting in June 2019 and accelerating through the fall, the number of migrants plummeted. Those with whom we talked disagreed on the explanatory weight for each, but they pointed to two causes.

First, in June, Mexico began deploying its National Guard, a new force meant to be civilian but for now made up mostly of military personnel, to its northern and southern borders to help interdict migrants. (A December 2019 WOLA report discusses the National Guard at Mexico’s southern border.)

Second, Mexico agreed to a vastly increased application of so-called “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP)—also known as “Remain in Mexico.” This program, launched in January 2019, sends most non-Mexican, Spanish-speaking asylum-seekers back to Mexico border towns, for weeks or months, to await their eventual hearing dates in the U.S. immigration review system. As of December 13, Mexico’s government reported receiving over 60,000 non-Mexicans under MPP.

The inability to access the U.S. border, or to pursue asylum cases inside the United States, caused family and child border crossings to fall so much that, by September, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced an “effective end” to the practice of releasing asylum-seekers in the U.S. interior to await their hearings—though some families from Mexico and non-Spanish-speaking countries are still being released. Today, the cavernous warehouse space that Annunciation House had been renting east of El Paso is nearly empty.

In November 2019, Border Patrol apprehended 5,084 people in the El Paso sector, while Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which manages official border crossings or “ports of entry,” allowed 1,727—many of them asylum-seekers—into the country. This is an average of 227 people apprehended or admitted per day; it is most likely that nearly all were either detained, deported, or placed into “Remain in Mexico.” A handful of families were released into El Paso, and most unaccompanied children were turned over to the Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Because they cannot be returned to Mexico—the country they’re fleeing—or blocked from traveling within Mexico, this 227 per day includes a higher proportion of Mexican citizens, including many asylum seekers. This is because fewer Central Americans are attempting the journey during the crackdown, and more Mexicans are doing so amid worsening violence and greater knowledge of the possibility of seeking U.S. asylum. In Ciudad Juárez, about 3,000 Mexicans came to this border zone in September, mostly from violence-torn areas along Mexico’s drug trafficking corridors: the Pacific zone states of Guerrero and Michoacán, and the central state of Zacatecas.

The deployment of Mexican National Guardsmen and “Remain in Mexico” are only two of several obstacles that have been thrown up this year in front of people seeking asylum in the United States. Asylum-seekers who try to enter the United States properly, by entering at a land port of entry, are “metered”: prevented from accessing the U.S. side by officers refusing to accept more than a few people per day. A new rule would ban asylum for anyone who did not first seek it in a country through which he or she crossed en route to the United States. Some non-Guatemalans are being sent back to Guatemala to seek asylum there, and the same may soon happen to non-Hondurans in Honduras. U.S. authorities are subjecting others, including Mexicans, to new pilot programs that dramatically reduce adjudication time and aim to issue credible fear decisions within days, while limiting access to counsel.

These hurdles are virtually insurmountable, essentially erasing the possibility of seeking asylum in the United States. Many of them have been piloted in the El Paso sector, where the initial 2017 trial of the Trump administration’s so-called “Zero Tolerance” policy led to U.S. border officials separating thousands of children from their parents in mid-2018. Nobody whom we interviewed could explain why El Paso so often gets used for pilot tests of harsh new border measures. Perhaps it’s because El Paso is one of the larger border cities and because—unlike San Diego, California—it’s not under the purview of the U.S. federal judiciary’s 9th Circuit, which is regarded as more liberal in its jurisprudence.

A Terrible 2019 in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez

January

The year begins with fallout from two December 2018 deaths of Guatemalan children in El Paso sector Border Patrol custody. Seven-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquín died of dehydration, shock and liver failure on December 8, and eight-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo died of influenza on December 24. Both had been apprehended with their fathers: Caal in a remote area of New Mexico, and Gómez in New Mexico after being held in El Paso.

March

As springtime brings an increase in arrivals of migrants, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) keeps hundreds in a pen under the Paso del Norte bridge for up to four days while they await processing.

May

A wave of mostly Central American migration crests, with 38,637 migrants—nearly 1,250 per day—apprehended by Border Patrol in the El Paso sector alone. Of these, 33,064 (86 percent) are parents or children.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) issues a report warning of “Dangerous Overcrowding Among Single Adults at [the] El Paso Del Norte Processing Center.”

A private “alt-right”-aligned group builds a half-mile of border wall on private property just west of El Paso, spending about $8 million of mostly online donors’ money, completing most work over Memorial Day weekend.

June

After President Trump threatens Mexico with tariffs if it does not crack down on migration, use of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, or “Remain in Mexico”) dramatically expands. By mid-December, nearly 18,000 non-Mexicans will have been sent to Ciudad Juárez to await their asylum hearings, out of more than 60,000 border-wide.

Attorneys inspecting an overcrowded Border Patrol station in Clint, east of El Paso, report on “appalling” and traumatic conditions for 250 children crammed there to await processing.

July

Aaron Hull, a much-questioned El Paso Border Patrol sector chief, is transferred away and replaced by agent Gloria Chávez.

August

A Dallas-based gunman driven by hatred of migrants opens fire in an El Paso Wal-Mart, killing 22 mostly Mexican and Mexican-American shoppers and wounding 24.

October

DHS rolls out the Prompt Asylum Claim Review (PACR) program, piloting it in El Paso. In November, it will do the same for the Humanitarian Asylum Review Process (HARP), which is applied to Mexican citizens. Both programs aim to adjudicate asylum claimants’ cases super-rapidly while they remain in CBP custody with almost no access to counsel.

A federal judge in El Paso orders a halt to some border-wall building, as part of a lawsuit against President Trump’s declaration of a “national emergency.” The decision suspends the use of $3.6 billion in Defense Department funds for construction. It is followed up in December by a nationwide injunction.

November

An organized crime rampage in Ciudad Juárez, an apparent retaliation for recent arrests of criminal leaders, kills at least 10 people and leaves burned-up buses scattered around the city.

In an effort piloted in El Paso, DHS begins sending some migrants to Guatemala to seek asylum in that country’s migration system, in compliance with a “safe third country” agreement first reached in July.

CBP expands MPP into its Tucson, Arizona sector by sending busloads of asylum-seeking migrants to El Paso, from where they are then returned to Ciudad Juárez.

U.S. law, which reflects international law commitments, states that any non-citizen may apply for asylum, regardless of how he or she enters the country, and be referred to an asylum officer. The non-citizen must demonstrate that his or her life or freedom would be threatened “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” If he or she meets this and other eligibility requirements, he or she may live and, after 6 months, obtain a permit to work in the United States, along with his or her spouse and children. (The Trump administration has proposed extending this waiting period to a full year.)

It is illegal to knowingly send people back to countries where they’re likely to be persecuted. That is called “refoulement,” and it is a bedrock precept of refugee and human rights law.

Because of a backlog of asylum claims—more than 1 million claims await just over 400 judges—asylum applicants’ cases now take years to conclude. During those years, adults who pass initial credible fear interviews are often detained in ICE facilities, but children may not be detained. Unaccompanied minors are sent to shelters run by ORR, then either transferred to relatives living in the United States or to foster homes. Because the Administration, under enormous political pressure, stopped the abusive practice of separating children and parents, parents with children are frequently given GPS location devices and released into the U.S. interior with instructions to appear later in immigration court.

The Trump administration has repeatedly referred to these interior releases as a “loophole” in U.S. immigration law, casting them as an incentive for people with weak asylum claims to seek entry in the United States. From its inception, the administration has chipped away at the right to seek asylum—and as we saw in El Paso, for now, at least, its work is nearly complete.

Even before these measures went into place, El Paso was already a very difficult place to win asylum. The city’s immigration courts raised “systemic due process concerns” because “detained immigrants are faced with near-impossible obstacles to accessing a fair day in court,” according to an April 2019 complaint filed by the American Immigration Council and the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Immigration Judges at the El Paso SPC Court granted only 31 out of 808 asylum applications (3.84 percent) between Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 and FY 2017. In FY 2016 and FY 2017 combined, judges at the El Paso SPC Court granted just seven out of 225 cases (3.11 percent).

Nationwide, by contrast, judges are granting asylum about 20 percent of the time, and many others are awarded some other form of protection because of danger in their home countries.

“Has the Department of Justice gone out of its way to select ‘hanging judges’ for this jurisdiction?” wondered a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), noting that, with many former Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) lawyers among its judges, the El Paso court has a culture that favors asylum denials.

Every day at 9:00AM and 6:00PM, U.S. authorities return a group of non-Mexican migrants to the foot of the Paso del Norte bridge in Ciudad Juárez. They are the latest asylum-seekers forced to “Remain in Mexico.” For now, the MPP program is limited to Spanish speakers, so Brazilians, Haitians, and others aren’t sent back. Nearly all MPP targets were Central Americans until June, when DHS started sending back Cubans, too. For now, the program doesn’t operate in Arizona, though some migrants are now being bused 300 miles from Nogales to El Paso.

U.S. immigration authorities assign “Remain in Mexico” migrants’ court dates according to how they were apprehended. Those who waited through months of “metering” to seek asylum at an official port of entry usually only have to wait a few weeks, perhaps a month or two, until the day when they may cross back to face an immigration judge. Those who did not wait, and were apprehended by Border Patrol between ports of entry, may have to await their court dates in Juárez for four or five months. (MPP cases get a higher priority than regular asylum cases, which routinely take years due to backlogs.) In both cases, it is routine to have to come back for two, three, or more court dates, which means many more months of waiting in Ciudad Juárez.

As of December 13, 2019, according to Mexican government data obtained by WOLA, 17,889 non-Mexicans had been sent back to Ciudad Juárez to await their court dates under MPP. Not all remain in the city; many have given up or had their claims rejected. In October, a Chihuahua state migration official, Enrique Valenzuela, told The El Paso Times that about a third of returnees have gone back to their home countries, another third are “in limbo, evaluating whether to go home, continue their process or cross illegally,” and another third, including many Cubans, “are settling into life in Juárez” by seeking asylum or another legal status.

The decision about what to do next gets more acute after a few court dates. If the likelihood of having asylum denied appears high, asylum-seekers face the choice of dropping their cases and requesting asylum or another permit to stay in Mexico, or going to court in the United States at the risk of being loaded onto a deportation aircraft back to Central America or Havana.

Mexico’s government acceded to the Trump administration’s demand for an expanded “Remain in Mexico” program after Trump took to Twitter at the end of May, threatening to slap ever-increasing tariffs on Mexican goods unless President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stemmed the flow of migrants and asylum-seekers through Mexican territory. Mexico’s government refused to sign a “safe third country” agreement with the United States, which would have compelled it indefinitely to take all non-Mexican asylum seekers who cross through its territory. Instead, it settled on expanded MPP as a compromise. In meetings described by U.S. immigration lawyers, Mexican diplomats have voiced fear that if U.S. courts strike down MPP, the Trump administration will likely use tariff or other threats to force Mexico to accept a safe third country pact.

Though Mexican diplomats insist that they still oppose the program, and are not accepting the return of especially vulnerable populations like pregnant women, the government’s position is not clear. Many pregnant women, as well as people with illnesses, have been forced to wait in Juárez, and WOLA and several other groups asked for more clarity about Mexico’s policies in a November letter. In August, Mexico’s federal government opened its first migrant shelter, in an industrial zone of Ciudad Juárez (discussed below). As of mid-December, the “Leona Vicario” facility is holding 750 people, nearly all of them Central American MPP targets, nearly half of them children.

The Mexican Army’s kitchen facility at the federal shelter.

Once MPP migrants get their days in court, they find it very difficult to argue their cases. Obstacles to due process abound. The process normally involves finding transportation from marginal Ciudad Juárez neighborhoods to the port of entry at 4:00 in the morning, then crossing the bridge just for a brief appearance.

Border-wide, according to Syracuse University’s TRAC database of hard-to-obtain official data, 9,974 MPP claims had been resolved by the end of September. Of these, only 11 cases—0.1 percent—had resulted in a judge granting asylum.

In El Paso by the end of September, TRAC data showed that hearings had occurred for 5,905 MPP targets. Of these, 3,491 (59 percent) had been willing or able to show up for the hearings; the other 2,414 had their asylum cases denied in absentia. Another 8,547 people were still awaiting their first hearings. Of these, only 32—0.3 percent—had lawyers to represent them. Lack of access to lawyers helps explain the near-impossibility of asylum for those forced to Remain in Mexico. “A dismal grant rate in MPP is plausible because there is so little due process, which is the direct result of a lack of access to counsel,” Linda Rivas, the director of El Paso’s Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, told The El Paso Times.

Representing migrants forced to remain in Mexico is frustrating for several reasons. First, attorneys who practice in the United States must be physically present in Mexico. “You can’t prepare someone for a full asylum hearing over the phone,” Rivas told WOLA. “These people are in shared spaces, like shelters. There’s no confidentiality.”

Second, attorneys can’t access MPP migrants to offer their services. Initial DHS promises to allow lawyers one hour to talk to clients have been dropped. Now, attorneys cannot even set foot in immigration courtrooms—even in a “friend of the court” status—unless they are already representing a client. “I was usually in the courthouse with MPP, but then I got blocked,” said Edith Tapia, a policy research analyst at the Hope Border Initiative. One attorney was even banned from bringing crayons and coloring books for asylum applicants’ small children to use during proceedings.

Third, being present in Juárez carries its own challenges for U.S. lawyers, who must meet with asylum-seekers in shelters that are often in marginal neighborhoods dominated by organized crime. And even then, cases can fall apart for the most frustratingly minute reasons: one attorney told WOLA of two women forced to drop their cases when, as they prepared to cross the border bridge for their hearings, they lacked the 25 cents (5 pesos) necessary to pay the bridge’s pedestrian toll.

Attorneys can savor some small victories, though. Las Americas has removed close to 90 people from MPP, usually for medical reasons. Even that, though, is hard. “Diabetes insipidus wasn’t enough” to get a client out of MPP, an attorney said. “Chronic urinary tract infections on the verge of kidney failure weren’t enough. …A child is sick. Why do we have to put in so many hours to save them, calling a million different people? It’s a level of exhausting we haven’t experienced.”

Even entering the “Remain in Mexico” program requires first that an asylum-seeking migrant set foot on U.S. soil and interact with a U.S. border official. Those who seek to do that without committing the misdemeanor of “improper entry” (Title 8 U.S. Code Section 1325) can do so by approaching one of the approximately 45 official land ports of entry, like three bridges over the Rio Grande between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez (Paso del Norte, Stanton/Friendship, and Ysleta/Zaragoza)

Since the spring of 2018, though, that has been harder to do. In the center point of the Paso del Norte bridge, right on the borderline, is an assemblage of canopies, jersey barriers, and concertina wire—what DHS calls “border-hardening measures.” There, CBP officers demand to see identification documents of all who attempt to set foot on U.S. soil, keeping those who lack them from approaching the port, where they would be legally entitled to ask for asylum. “We’re full, come back later,” asylum seekers are told. CBP is processing approximately 10 non-Mexican asylum seekers plus 2 or 3 Mexican families per day at the bridges, according to a November report from the University of Texas’s Strauss Center and the University of California at San Diego’s Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies.

This is “metering,” a border-wide practice that has forced asylum-seekers to wait, inscribed on informal first-come-first-served lists, in Mexican border towns from Matamoros to Tijuana. Metering is facing a legal challenge, a class-action suit (“Al Otro Lado vs. <name of current DHS secretary>”) moving slowly in federal courts since July 2017.

The U. Texas-UCSD report found about 21,398 asylum-seekers on waitlists in Mexican border towns in November. This is down from about 26,000 in August: a symptom of an overall decline in migration across Mexico amid Mexico’s security deployment and “Remain in Mexico.” In Ciudad Juárez, about 7,100 were on two lists: about 4,101 non-Mexicans waiting their turn, and about 3,000 Mexicans on three sub-lists, one for each bridge.

A Chihuahua state agency, the State Population Council (COESPO), manages the non-Mexican list, while migrants themselves run the Mexican lists. COESPO and Mexican migrant representatives check in with CBP daily to find out how many asylum-seekers the officers will be accepting. They apparently base their decisions on space and personnel constraints.

With Central Americans dwindling, Juárez’s non-Mexican waitlist is now heavily Cuban. “Some 80 percent of the individuals on the list are from Cuba, 12 percent are from Central America or other countries, and the remaining 8 percent are from Mexico,” according to the U. Texas-UCSD report. “However, COESPO reports that most, if not all, of the Mexicans registered on their list have switched to the Mexican-only lists at the bridges.”

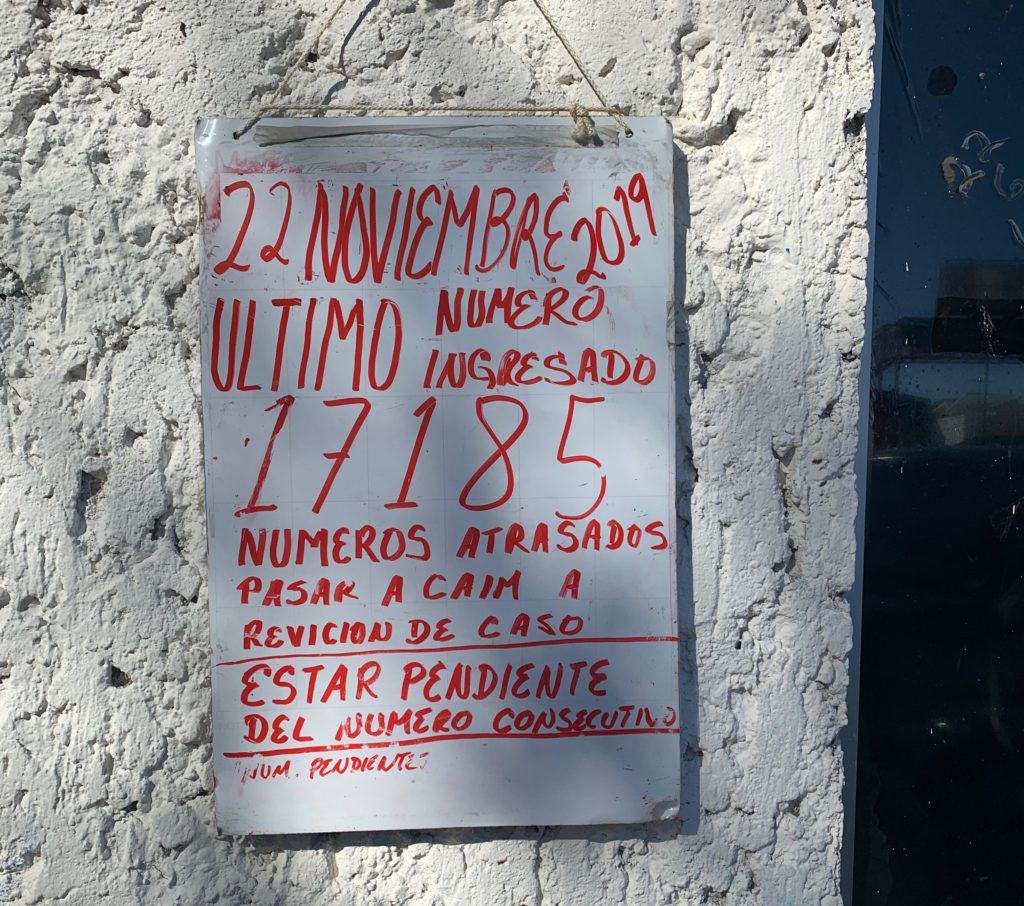

The most recent number on the non-Mexican list.

The most recent number on the non-Mexican list.

As of mid-December, it was not clear to what extent the non-Mexican list was still in use, given the likelihood of having to “Remain in Mexico” or being deported. Those being “metered” must each take a number to await their turn, but the latest number posted outside COESPO had not been updated since November 22.

CBP denies that it is “metering” Mexicans, which could be a form of refoulement because Mexican asylum seekers are stuck in the same country they are fleeing. “CBP does not have a policy to ‘meter’ Mexican nationals,” a CBP spokesperson told Vox in November. “We queue undocumented aliens based on operational capacity.” (It’s unclear how that is distinguishable from metering.) The U.S. government argues, Vox continues, that “Central Americans can be subject to metering because they are ‘safe’ from persecution in Mexico (though advocates have also argued that isn’t true).” WOLA is among those advocates.

Border-wide, Mexicans—mostly fleeing violence during a year in which Mexico is on track, again, to break its annual homicide record—now make up more than half of all migrants on asylum waitlists. In Ciudad Juárez, most Mexicans are insisting on staying near the border bridges, both because they feel unsafe and because they fear losing their places in line. “They insist that they don’t want to move because they need to be right there, paying attention,” Valenzuela, the state migration official, told The El Paso Times. “Basically, they don’t completely trust the mechanism they themselves created.” The largest number, about 3,000, arrived in a September wave from Guerrero, Michoacán, and Zacatecas.

Mexican asylum seekers’ tents near the Paso del Norte bridge.

Mexican asylum seekers’ tents near the Paso del Norte bridge.

Along a tiny street near the Paso del Norte border bridge are two rows of tents and plastic tarps, in which dozens of adults and children are staying—with no reliable access to water, electricity, or sanitation—even as December’s nighttime temperatures drop into the 30s Fahrenheit. Similar encampments exist along the two other bridges. A Ciudad Juárez-based attorney told us that the current count of Mexicans living in this squalor is about 598, down from over 1,000 about a month ago.

As they are Mexican citizens, the local government cannot obligate them to vacate the encampment; if they were Central Americans, security forces would have long since cleared them out, forcing them to seek shelter elsewhere. Instead, “the Mexican asylum seekers are trapped in a no-man’s land, essentially stateless,” an El Paso-based journalist told us.

El Paso is one of the United States’ most isolated metropolitan areas, with few similarly sized cities within 500 miles. Asked why asylum-seekers would choose to come to this part of the border, a Juárez-based human rights advocate noted that migrants first chose to go to Tijuana because Mexico’s northeastern state of Tamaulipas—the part of the border closest to Central America—was too dangerous. Tijuana is where migrants pioneered the first metering waitlist. After Tijuana filled up, “Word was that you could cross more quickly with less waitlist in Juárez.” The neighboring state of Coahuila even put migrants on Juárez-bound buses.

Some of the asylum-seekers on Juárez’s waitlists “have real fear, but they’re the minority,” a municipal human rights official insisted to us. The wave of Mexicans who came in September, this individual alleged, were drawn by smugglers’ false messages that those who come to the United States by December 31 would receive automatic residency. We did not hear this elsewhere, and a December 9 New York Times article disputed it.

[T]wo dozen migrants interviewed in the Ciudad Juárez encampments said their decision had nothing to do with a smuggler’s marketing appeal. All said they were fleeing violence. Some said that there had been a shift in the nature of violence in their home regions. Others said that while they had suffered violent persecution for months if not years, they only just learned about asylum and their possible eligibility.

Between Remain in Mexico (nearly 18,000) and metering (about 7,000), as many as 25,000 people who intended to seek asylum in the United States could be stranded in Ciudad Juárez. The actual number, however, is assuredly lower. The Juárez municipal human rights official estimated that perhaps 7,000 to 10,000 people remain in the city. In September, Mexican officials cited by the Associated Press estimated that there were about 13,000. “The vast majority have returned to their places of origin, many very disappointed.”

On the non-Mexican waitlist, the U. Texas-UCSD study finds, “For every ten numbers called, the list may advance 100 to 150 spots, given that many asylum seekers do not show up. COESPO believes that some of these asylum seekers may have crossed the Rio Grande and attempted to enter the United States undetected or returned to their countries of origin.” Some may have gone to Monterrey, a prosperous and relatively safer city several hours’ drive away and further from the border, a human rights advocate said, adding that others may have gone to the neighboring state of Sonora after suffering criminal aggression in Juárez. Still others have desisted their asylum claims and opted for the free bus rides back to El Salvador and Honduras offered by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), through a program funded by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

Other than the Mexicans in tents near the bridges, those who stay in Juárez are scattered around the city in apartments, cheap hotels, group houses, and a network of about 17 shelters: the large new Leona Vicario facility run by the federal government, and smaller ones run mostly by churches. When WOLA last visited Juárez in 2016, the city had just one shelter: a Catholic Church-run “Casa del Migrante” that catered mainly to single adults who were either northbound or recent U.S. deportees. Of the new facilities, four are receiving support from IOM for infrastructure improvements, a shelter director said.

“Mexican authorities counted 1,486 people in the city’s network of nonprofit shelters in late November,” The El Paso Times reported. Most of those in the shelters are asylum seekers made to remain in Mexico. In stark contrast to Annunciation House across the river in El Paso, these shelters are full, though down from their mid-year highs.

For instance, the Buen Pastor facility, run by a Methodist pastor, had 79 people on December 12, down from a high of 260 earlier in the year. Of those 79, 58 were MPP targets, 8 were on the non-Mexican waitlist, and 13 were on the Mexican waitlist. By nationality, 21 were Honduran, 18 were Guatemalan, 15 were Mexican, 14 were Salvadoran, 6 were Cuban, and 5 were Nicaraguan.

With half the city’s shelter population, the federal government facility has three gigantic rooms, for men, women, and families, with ranks and files of bunk beds stretching for tens of thousands of square feet. At first, this shelter expected to limit occupants to a three-week maximum stay while they got situated in Juárez. In practice, that has been extended to the MPP migrant’s first asylum hearing—and appears to be extending further, when necessary, for subsequent hearings. Mexico’s Army is in charge of preparing and serving meals, and representatives of the federal Labor Department offer documents and other services to help migrants find income-generating jobs. Most single parents, though, are reluctant to leave their children behind when working.

The shelters, many of them staffed by people with little prior social-work experience, are struggling with demand and lack of resources. A 57-year-old Cuban migrant, Magaly Medina Calvo, died in the federal shelter in early December after being very ill for days and receiving insufficient attention. Electricity shortages have affected shelters’ ability to operate medical devices. WOLA staff noted that shelters often kept their doors open, a potential security vulnerability.

Asylum seekers are not safe while they wait in Ciudad Juárez. A group of U.S.-based shelters and respite centers has begun using the social media hashtag #UnintendedTies, with a graphic of a shoelace, to draw attention to what happens to migrants forced to wait in Mexican border towns:

U.S. officials take shoelaces from asylum seekers so that they don’t harm themselves in detention. But then they send families with children back to dangerous and unfamiliar Mexican border towns. There, human traffickers and cartels target these families for extortion and trafficking because no shoelaces means no local connections. The “Remain in Mexico” policy delivers families into the hands of cartels and traffickers.

A migration policy expert in El Paso likened the U.S. government’s MPP returns to the 2009-11 “Fast and Furious” scandal, when U.S. agents purposely allowed firearms dealers to sell to cartel buyers, then lost track of the weapons. “Instead of guns, we’re handing human bodies to the cartels with which to make money.”

A local attorney highlighted the danger of the 6:00PM “Remain in Mexico” dropoff by the border bridge, especially in the winter months after the sun has set. Organized crime lookouts, called halcones (hawks), “are everywhere near the port of entry,” and some MPP returnees have been kidnapped on the street just outside the reception area. Kidnappers demand ransom from relatives in the United States; “it usually starts at US$10,000, then gets negotiated down to $3,000 to $5,000.”

Human Rights First has documented at least 52 cases of violent crimes against migrants forced to remain in Juárez, including rapes and kidnappings in addition to assaults and extortion. “One woman was raped on her way to the store” from a shelter, a Ciudad Juárez-based rights defender told us. “People don’t want to leave the shelters. Organized crime carries out rondines (patrols) around them.”

Criminal groups have even, on a few occasions, raided shelters and kidnapped migrants staying there. A migrant at the Pan de Vida shelter told us of an August incident that was also reported in The New Yorker: “a truck full of armed men in masks circled the grounds of the shelter a few times, and then left.” When kidnappings occur, shelters rarely dare to report them to authorities, for fear of further criminal retribution. Too often, local police may be linked to, or dominated by, the same criminal groups.

“MPP should be a ‘particular social group,’” said the migration expert who made the “Fast and Furious” comment, referring to the terminology used in the law to judge eligibility for asylum. In Juárez and other border towns, “you’re targeted literally because you’re in MPP.”

In addition to the ever-present threat of violence, and their uncertain housing and work situations, migrants in Juárez must face extortion and other mistreatment at the hands of authorities. The local delegation of Mexico’s migration authority, the National Migration Institute (INM), is “bad news,” said an El Paso-based lawyer, citing extensive corruption and collusion with organized crime. The delegation’s newly named chief is a retired Mexican Army colonel, and his deputy is a young member of President López Obrador’s political party. Neither has a background in migration.

Despite these challenges, a growing number of migrants in Juárez, especially Cubans, are deciding to apply for asylum in Mexico, a decision that nearly 67,000 people have made nationwide so far this year. Like many northern Mexico cities, the Juárez economy is growing, and jobs are relatively easy to obtain.

The asylum process is difficult, however, because Mexico’s overwhelmed refugee agency, COMAR, has no presence in Ciudad Juárez and very little presence along the northern border. Many applicants are waiting a year for their first interviews, said a Ciudad Juárez-based migrants rights defender, and the whole process happens over a long distance. “Everything happens through DHL [the express delivery service] to Mexico City, and files get lost.” COMAR sent three asylum officers to Tijuana in July, and plans to open new offices in Tijuana and Monterrey—both far from Juárez—in 2020.

Of asylum-seeking migrants made to wait in Ciudad Juárez, the thousands of Cubans are probably the most vulnerable. Criminal groups target those who fled the island, kidnapping them with the expectation of collecting ransoms from U.S.-based relatives. Monitors like Human Rights First note many examples of violent crimes committed against Cuban migrants subjected to MPP, particularly in Juárez and Nuevo Laredo.

Beyond a lack of shoelaces, Cubans stand out from the population because of their accents, their clothing, even “the way they carry themselves,” as a shelter director put it. “They’re learning to survive and to be safe here. They’re not obvious unless they speak. They’re learning how to blend in with Mexicans. They’re avoiding going out at night. They only communicate with relatives, not strangers.”

Though a U.S. law-enforcement official in El Paso said that Cuban migrants are “more pro-American” than others, and “want to contribute and help” in the United States, a growing number are deciding to put down roots in Mexico. Some are seeking asylum through COMAR, and a few are getting married to Mexicans to seek residence, said a Juárez-based human rights defender.

Nearly three years after the outgoing Obama administration abandoned the “wet foot dry foot” policy that automatically paroled into the country all Cubans who reached U.S. soil, their chances of winning protection in the United States have shrunk. ICE deportation flights began arriving more regularly in Havana in August and September; the agency reported repatriating 1,179 Cubans in 2019, up from 463 in 2018 and 160 in 2017.

Most are living in hotels or rented houses near Ciudad Juárez’s dilapidated downtown. There, they have started up at least three restaurants, among other businesses. “They are the most resistant, but they’ve begun to give up on the United States being helpful,” said the human rights defender.

Migrants of African origin, for instance from African countries or Haiti, come in large numbers to Tijuana, but very few currently arrive in Ciudad Juárez. The few black migrants who are present in the city, for instance Garífuna people from Honduras, are especially at risk—likely more so than Cubans—because they stand out and more easily gain criminals’ unwanted attention. “Black migrants shouldn’t be MPP’d. They’re so much more vulnerable,” an El Paso-based asylum attorney told us. Of three Afro-Latino clients this individual is representing, two have been raped in Mexico.

“Remain in Mexico” and metering are not the only asylum obstacles that the Trump administration has instituted. Effective July 16, 2019, DHS and the Department of Justice (DOJ) issued an “interim final rule” (a rule that goes into effect immediately) blocking all asylum seekers at the border who did not first apply for asylum in a country through which they crossed en route to the United States. This rule’s effect would be to ban asylum for nearly everyone arriving at the border except Mexicans, who don’t cross through another country.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and others immediately challenged the rule in federal courts. In September, the Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to implement the rule while lower courts consider it. However, in November the organizations succeeded in convincing a federal judge to block application of the ban for asylum seekers who were on the waitlists prior to July 16. Non-Mexican asylum seekers who did not access the border before July 16 risk being turned away at the U.S. border and told to seek asylum in Mexico or another country through which they passed.

Under heavy pressure from the Trump administration, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador have agreed to sign some forms of “safe third country” agreements. DHS calls them “Asylum Cooperation Agreements” (ACAs). These accords, signed between July and October, will allow the U.S. government to send asylum seekers directly to the Central American nations’ territory, where they would enter those countries’ barely existent asylum systems. Unlike “Remain in Mexico,” there would be no eventual U.S. hearing date. The returnees would have to seek asylum in those countries.

This is of course absurd: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras lack asylum infrastructure, and conditions there are so dangerous that hundreds of thousands of their citizens fled in 2019. “These agreements will only further trap families, men, women, and children in precarious conditions without any meaningful access to protection,” reads a December 5 statement from WOLA and several other organizations.

Though it may be absurd, it is happening. DHS began sending citizens of El Salvador and Honduras to Guatemala on November 19, 2019. The program is known as GACA (Guatemala Asylum Cooperation Agreement), and as is often the case, it is being piloted in the El Paso sector.

In its first week, GACA sent 14 people—11 Hondurans and 3 Salvadorans—from El Paso holding facilities back to Guatemala to seek asylum there. These were individual adults, but by December 10, the Los Angeles Times reported, DHS had begun notifying some families that they, too, would be going to Guatemala.

In November, Guatemala’s interior minister indicated that GACA targets’ planes might land in the remote, ungoverned, violent department of Petén in the country’s far north. This proposal gave U.S. officials “unease,” the Washington Post reported, and so far the returnees’ flights have taken them to Guatemala City.

Another new obstacle to asylum is a pair of programs now being rolled out in the El Paso sector: Prompt Asylum Claim Review (PACR), which DHS is applying to non-Mexicans, and the Humanitarian Asylum Review Process (HARP) for Mexicans. Both initiatives aim to adjudicate asylum seekers’ cases at a blisteringly fast pace with weak due process guarantees.

PACR and HARP operate similarly: the initial asylum process occurs while asylum-seekers are in Border Patrol custody. They are given one day to call family or a lawyer. Then they have a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer, usually within 48 hours. Those who pass this interview then begin the asylum process: single adults usually go to detention, while families are released with a hearing date. Those who fail may appeal to an immigration judge, but if turned down may not apply for asylum, and are quickly deported.

As of late November, CBP statistics showed PACR applied to 392 people: 285 Guatemalans and 107 Salvadorans, both single adults and family unit members. As of December 12, an attorney told us that 90 percent of those subject to HARP had failed their initial credible fear interviews. A 10 percent success rate is well under half what was the norm before late 2017, when credible fear findings began to plummet in the U.S. asylum system.

Attorneys in El Paso don’t find this rate surprising, given the process. Migrants subjected to PACR and HARP are taken to a tent facility at the El Paso Border Patrol’s “Station One,” which opened in August. One lawyer reported hearing of 32 PACR and HARP clients being held in cells marked “capacity 11.” There, the credible fear interview takes place by telephone. Attorneys may not enter Border Patrol stations, and can only speak with clients by phone for about half an hour. They are not on hand for the credible fear procedure.

If an asylum-seeker wishes to appeal his or her credible-fear denial to one of a few New Mexico-based immigration judges, only then may an attorney be present for the review. “It is impossible for everyone to have meaningful access to counsel within 48 hours and that is the entire intent of the program,” Taylor Levy, an El Paso-based immigration attorney, told BuzzFeed. “Even if we do get calls from family members, we aren’t able to see those people or meet with those people.”

In early December, the Las Americas advocacy center and the ACLU filed suit against PACR and HARP in Washington, DC federal court, citing severe due process shortcomings. ACLU Border Rights Center lawyer Shaw Drake said he expected the case to move after the holidays.

In the meantime, an attorney in Ciudad Juárez said that HARP families tend to stay at the tent camps near the border bridges for the first few days after being returned. “They have nowhere to go. ‘My house was burned back home,’ they say.”

A migration expert in El Paso says that HARP is responsible for much of a recent reduction in Mexican asylum seekers waiting to be “metered” at the border bridges, speculating that perhaps 1,000 of those on the 3,000-person list may actually still be there. The number of Mexican asylum seekers remains relatively high, though, and may grow further when springtime brings more temperate weather, which means HARP is likely to become a bigger issue in 2020—if courts don’t block it first.

The border’s El Paso sector gained notoriety in 2019 for more than just piloting new obstacles to asylum. Much media coverage highlighted the shocking conditions of migrants being processed in overcrowded Border Patrol facilities, while local advocates called attention to migrant deaths, use of force, and community relations issues.

“Processing” refers to the first stage of what happens after a migrant ends up in Border Patrol custody. Those who wish to apply for asylum fill out forms, are fingerprinted, have their backgrounds checked against databases, and are presumably checked for communicable diseases, among other tasks. Under non-emergency circumstances, processing must happen within 72 hours, especially if children are involved. For some reason, these largely administrative tasks have been left almost entirely up to armed, uniformed agents at Border Patrol stations, instead of specially trained civilians.

Lack of processing capacity—space and personnel—is the reason that CBP gives for “metering” the number of asylum seekers who may approach ports of entry each day. Border Patrol cannot meter, though: agents apprehend migrants who have already found another way to reach U.S. soil. (That is especially easy to do in Texas where the border is a winding river, and there is always U.S. soil between the riverbank and any existing border fence.) If large numbers of asylum seekers do that, Border Patrol must process them as they apprehend them, regardless of whether they have space or manpower.

During the mid-2019 wave of child and family asylum seekers, Border Patrol’s lack of processing (and problem-solving) capacity caused the situation to devolve into horror.

The first serious signs of trouble came in December 2018, when two Guatemalan children—both apprehended with their fathers—perished in Border Patrol custody. Seven-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquín died of dehydration, shock, and liver failure, and eight-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo died of influenza. Border Patrol had apprehended both in very remote areas of New Mexico’s desert, far from hospitals. They arrived with some of the first large groups that smugglers were dropping off in that region. These groups quickly overwhelmed Border Patrol’s rustic facilities. The media record shows numerous advocates, editorialists, and members of Congress at the time blaming agents for failing to respond promptly to the children’s symptoms.

In March, as arrivals began to increase, Border Patrol held hundreds of adults and children in a chain-link pen for four days under the Paso del Norte bridge leading into downtown El Paso. In May, the DHS Inspector-General issued an urgent report about overcrowding of single adults at the Paso del Norte Processing Center next to the bridge. There, detainees wore “soiled clothing for days or weeks” and were “standing on toilets in the cells to make room and gain breathing space.” In June, a group of attorneys carrying out an inspection of the Border Patrol station in Clint, east of El Paso, found hundreds of children crammed—in some cases for weeks—into spaces originally designed for single adults’ short-term stays. Teenagers were caring for younger children, while all lacked toothbrushes and places to sleep, subsisting on microwaved burritos and ramen noodles while “wearing clothes covered in snot and tears,” as the Santa Fe New Mexican put it.

According to El Paso’s Border Network for Human Rights, the “most egregious documented abuses” included

a. Lack of adequate access to food and water in detention, including detainees being denied drinking water and being provided food that was moldy or spoiled; b. Severe overcrowding; c. Lack of access to adequate medical care—multiple reports involved migrants being told they could not see a doctor unless they fainted or were dying; d. Separation of family units by CBP; e. Lack of access to bathing or hygiene—multiple women reported that they were denied access to feminine hygiene products such as tampons while in CBP custody; and f. Verbal and physical abuses by CBP personnel.

On that last point, a Juárez municipal official told us that migrants often complain of being called “cerdos centroamericanos” (Central American pigs) and similar while in U.S. custody.

Border Patrol agents defend their actions during the migrant surge. They were spending US$60,000 per day on “supplies for family units,” cannibalizing the sector’s vehicle maintenance budget, agents told us. “We were going to Sam’s Club to get supplies,” and many were bringing DVDs, toys, and diapers, often spending their own money. Aaron Hull, the El Paso sector’s chief at the time, insisted to reporters that “children are given a toothbrush each night that is thrown away after use.” An agent told us that “conditions at Clint weren’t bad at all compared to life in Central America.”

Border Patrol agents and migrant advocates agreed that much more resources must go into fixing migrant processing bottlenecks. All agreed in principle with the idea of asylum seekers being allowed to approach ports of entry, then being immediately bused to large facilities with the capacity to process them. These short-term facilities would operate under conditions far superior to the ultra-austere warehouse-like structures that many observers have called “kids in cages.” There, processing would mostly be up to civilian personnel, perhaps contractors, trained to work with children and trauma victims. The contracting of these civilians, an El Paso-based attorney cautioned, should be a fully transparent process with opportunities for meaningful outside input.

In March, Congress passed a 2019 Homeland Security appropriations bill providing US$192 million to build such a processing center in El Paso. This facility’s construction has been delayed, though, by objections from businesses and residents near the chosen site. For now, the 1,500-capacity tents at Border Patrol’s Station One are where most processing occurs. Meanwhile, it’s not clear how much use any facility will get as long as the Trump administration is able to continue MPP, metering, the July 16th rule, GACA, PACR, HARP, and other initiatives that have all but eliminated the right to seek asylum in the United States.

Some migrants still seek to evade capture, and their numbers may grow as asylum becomes an impossibility. This will probably bring an increase in the number of migrants who die of dehydration, exposure, or drowning in New Mexico or west Texas wilderness, and elsewhere along the border.

Border Patrol had found relatively few remains of migrants in the El Paso sector lately: four in 2018, out of 283 border-wide. But a preliminary count for 2019 shows a jarring increase, as more migrants succumb in deserts or in fast-flowing irrigation canals. “This year, to date, we have 15 deaths. Nine of those have been in the waterways,” Fidel Baca, a spokesman for the El Paso sector, told a local TV station.

The Rio Grande from the Paso del Norte bridge.

The Rio Grande from the Paso del Norte bridge.

At the Border Network on Human Rights, advocates lamented a reversal of hard-fought progress on Border Patrol’s use-of-force standards and community relations. After regular community forums and work with Border Patrol on assessing past use of lethal force—what it calls a “pressure and dialogue strategy”—the BNHR had seen the agency’s responsibility for use-of-force incidents in the sector fall to “minimal” levels between 2000 and 2014. “We went entire years without complaints about Border Patrol behavior, it was like a bubble here,” said director Fernando García.

“In 2016, with the election of the Trump Administration, everything changed,” the BNHR reports. In 2017 Border Patrol named a new sector chief, Allen Hull, who only met once with BNHR during his entire tenure. Hull was at the helm during all of the processing horrors described above, and also oversaw reversals on use of force. “The 2000 numbers are back,” said García, citing “Border Patrol [agents] in houses, reckless driving, crashing into homes, questioning children, throwing milk on the ground instead of giving it to kids in custody.”

An El Paso-based journalist and some UTEP professors blamed Border Patrol’s “paramilitary” culture for some of this year’s complaints. “Any military force needs an enemy,” one observed. “They don’t like asylum,” added another. “Even in 1991-92 they thought it was a ‘scam’ and resented it. Their view of immigration is ‘it’s a system of laws’ but also, ‘everybody is maneuvering illicitly to try to get into the United States.’ They’re convinced they’re the ‘thin green line’ defending against the ‘hordes.’”

The journalist and scholars placed less blame on the agents themselves, though, than on managers who put them in impossible positions, like trying to care for hundreds of children in tiny Border Patrol stations under medieval circumstances. “These guys hit their breaking point,” the journalist observed. “They’re like, ‘this isn’t what I signed up for.’ …They lost touch with their humanity in the crisis, dehumanizing migrants as a defense mechanism, referring to them as ‘aliens’ or ‘bodies’ instead of people. It was a way not to lose your mind.”

Chief Hull was abruptly transferred out of the El Paso sector in July. The new chief, Gloria Chávez, has since met with BNHR four times. But “we can’t work under the notion that one chief is going to be good and the next bad,” say BNHR staff. They are proposing the creation of a new position: an “ombudsman” carrying out community relations and overseeing a complaint process for all DHS agencies in the sector. “Someone who is above, and can keep them [DHS components] from kicking the can from agency to agency,” said Policy Director Robert Heyman. An ombudsman is a central feature of H.R. 2203, the “Homeland Security Improvement Act” sponsored by El Paso Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), which passed the House in late September but awaits consideration in the Senate.

Though it does little to deter asylum seekers, there’s another barrier in the El Paso sector: a fence. The Secure Fence Act of 2006 authorized the building of 110 miles of pedestrian barrier along the sector’s 268 miles of border with Mexico, and the Trump administration is endeavoring to upgrade or build more.

In the El Paso sector, the new construction is proceeding as follows:

President Trump had wanted much more—$5.7 billion—for wall-building in 2019, and the resulting dispute brought a 35-day partial government shutdown between December 2018 and February 2019. After settling for less money from Congress, in February Trump issued a “national emergency” proclamation leading to the transfer of about $6.7 billion from the Defense Department’s budget and from the Treasury Department’s asset forfeiture funds.

The Supreme Court has allowed most construction to go forward while courts debate the legality of this transfer against the will of Congress. Congress has voted twice to reject the emergency proclamation, but lacked the two-thirds majority necessary to override President Trump’s vetoes.

In the El Paso sector, this “emergency” money would pay for a lot of fencing in areas of very little human habitation, where smugglers took large numbers of asylum-seeking child and family migrants during late 2018 and the first half of 2019:

A February DHS document claims that the new construction is necessary because “transnational criminal organizations quickly adapted their tactics” in the New Mexico desert by “switching to foot traffic, cutting the barrier, or simply driving over it to smuggle their illegal cargo,” a situation “further complicated by the close proximity of New Mexico Highway 9 to the border.” As WOLA’s 2016 El Paso report documented, however, fences make little difference in far-off regions like New Mexico’s Bootheel, where “the five to ten minutes that a border-crosser must spend scaling a fence” means little, and where it is difficult to repair fences that get vandalized.

Arguing over the border fence’s effectiveness misses the point, a much-cited El Paso-based analyst contended, since President Trump is using the fence mainly as a rallying cry for a larger agenda. “It’s symbolic politics. It has no effect on border management.”

Some of the fence-building plan is in limbo. A federal lawsuit brought by the Border Network on Human Rights and El Paso County resulted in El Paso District Court Judge David Briones ruling that some of the “national emergency” money was granted in violation of the 2019 appropriations law. That ruling came on October 11; on December 10, Briones issued a nationwide injunction blocking $3.6 billion of the funding, an amount the White House had sought to cut from military construction projects. $2.5 billion remains available from money transferred into the Defense Department’s counter-drug account. A law passed at the height of the drug war, in 1990, allows the Pentagon to use its budget to build border barriers to block trafficking.

This isn’t, however, the only border fence to be built lately in greater El Paso. A private group called “We Build the Wall” spent about US$8 million for a half-mile of fencing, much of it built in late May 2019. The project, built on private land owned by an 85-year-old Air Force veteran, climbs up a steep hill a few miles west of El Paso. It was funded by individual donors, mainly through the website GoFundMe.com, and construction was carried out by Fisher Industries, a North Dakota-based company—headed by an outspoken supporter of President Trump—that has won some questionable border fence-building contracts. The board of “We Build the Wall” includes alt-right former Trump official Steve Bannon, Blackwater founder Erik Prince, and Kansas’s anti-immigrant former secretary of state Kris Kobach.

Construction was slowed by the organization’s failure to secure permits from the city of Sunland Park, New Mexico, which borders El Paso. “Attempts by city officials to intervene were immediately met with a barrage of angry and even threatening emails, phone calls and social media posts from supporters of We Build the Wall,” reported Yahoo News. The U.S. International Boundary and Water Commission “was also scared by the threats that they ginned up,” an El Paso-based attorney told us.

Today, the new fence sits between Sunland Park and Anapra, a marginal sector of Ciudad Juárez. It bears a banner with the private group’s logo, and includes a gate that is nearly always kept open.

On its side of the border, Mexico has also beefed up security measures to hinder irregular migration. The same White House tariff pressure that convinced Mexico to agree to an intensified “Remain in Mexico” program also led President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to deploy members of a brand-new constabulary force, the National Guard, to the country’s northern and southern borders. WOLA’s December report on Mexico’s southern border discusses the National Guard deployment in that region. In Mexico’s north, in states that border the United States, guardsmen—nearly all of them temporarily assigned soldiers and marines—total nearly 10,000, with only a small fraction posted near the borderline.

A National Guardsman buys cigarettes from a vendor near the Paso del Norte bridge.

A National Guardsman buys cigarettes from a vendor near the Paso del Norte bridge.

Though it is intended to be chiefly a public security and crimefighting force, the pressure from the Trump administration made migrant interdiction one of the National Guard’s main inaugural missions. In June and July, U.S. and Mexican media ran dramatic photos of guardsmen in Ciudad Juárez physically restraining and otherwise keeping anguished-looking migrant families from crossing.

Today, Mexican soldiers wearing “GN” (Guardia Nacional) armbands are visible along the borderline, patrolling alone. There are very few of them in central Juárez; a local human rights defender said they are more concentrated on the city’s fringes, where migrants are more likely to seek to cross the border irregularly. Most agreed that the overall National Guard presence in the Juárez border zone is sparser than it was in June or July.

At least in Ciudad Juárez, the National Guard “seems focused just on stopping migrants, not crime,” said a UTEP professor. WOLA staff observed that the guardsmen seemed more likely to stop a migrant family from crossing the border than a drug trafficker with a backpack, to which a local journalist replied, “Well yeah, they’re not stupid.” Organized crime groups are active and very powerful in Juárez, and it is risky for all, even soldiers, to interfere with their business.

That business is booming, but the groups that dominate it are becoming more violent and fragmented. At the beginning of the 2010s, Ciudad Juárez had perhaps the highest homicide rate of all large cities worldwide, as the Sinaloa cartel brutally wrested control of the cross-border drug trade away from the Juárez cartel. Several years of relative calm followed Sinaloa’s achievement of a criminal monopoly, along with some modest advances in policing and community investments. But today, Sinaloa’s dominion is eroding. New challengers are rising, including a revived Juárez cartel, and the city is becoming violent again.

Ciudad Juárez recorded 1,143 murders during the first nine months of 2019, which for a population of 1.5 million would set the city on track toward a sky-high rate near 100 homicides per 100,000 residents. Criminal groups are showing muscle, particularly a November 5 rampage, apparently triggered by a few trafficker arrests, that killed at least 10 people and left burned-out buses blocking streets around town. “A year ago, I would’ve said that violence is really high, but limited to the colonias,” said a UTEP professor, referring to Juárez’s poor, marginal neighborhoods with little police presence. “But now, it’s getting into more central spaces.” Border Patrol agents said that U.S. authorities are seizing greater quantities of harder, low-volume drugs like methamphetamine, cocaine, and opioids, especially at ports of entry and road checkpoints.

Worsening criminality of course makes conditions more dangerous for the thousands of migrants living in Mexico as a result of MPP and metering. The threat comes more from mid-level and low-level criminals, though, than from large organized crime syndicates. The big “cartels,” the UTEP professor explained, are more focused on drug trafficking. To the east, in the hyper-violent state of Tamaulipas, it is more common to see larger criminal groups like the Zetas, Northeast, and Gulf cartels (and their offshoots) preying on migrants. Despite this, the “Remain in Mexico” program is robustly returning migrants to two Tamaulipas border cities, Matamoros and Nuevo Laredo.

Though we saw none of them during our December visit to El Paso, the Trump administration has also sent soldiers to the border: deployments of the U.S. National Guard and—in a highly irregular move—active-duty military personnel. President Trump ordered both missions in 2018, as a putative response to that year’s much-hyped migrant “caravans.” Though neither deployment has ended, the soldiers are mostly out of sight, manning Border Patrol’s camera-monitoring rooms, maintaining vehicles, and scanning the line with binoculars, ready to alert Border Patrol if they see anything. The presence appears to be reduced since mid-November, an El Paso-based attorney said, though guardsmen can still be seen performing secondary vehicle inspections at ports of entry.

2019 in El Paso was a year of massive migration followed by a relentless crackdown, leading to the effective end of threatened foreign citizens’ longstanding ability to seek asylum in the United States. Since June, migration has been trending sharply downward, leveling off a bit in November. But it is impossible to predict what might happen in 2020.

We’ve seen asylum-seeking migration plummet before amid crackdowns or fears of crackdowns, in 2014 and 2017, only to recover both times in a matter of months. That will almost certainly happen again, despite the Trump administration’s draconian efforts, either in 2020 or soon afterward. The factors that are driving Central Americans to migrate haven’t gone away. Nor have the factors that are channeling profits to smugglers.

For now, though, “smugglers are waiting and seeing,” said Rubén García, the director of Annunciation House. The U.S. asylum system has become so confusing, and policies keep changing with such rapidity, that now “there are so many outcomes and moving pieces that the uncertainty still drives people to come,” said a UTEP professor.

It is quite likely that more child and family migrants may seek to avoid apprehension next year, traveling through the deadly deserts of the southwestern United States at enormous personal risk. It’s also likely that more Mexicans, fleeing record levels of violence and not subject to “Remain in Mexico,” may opt for the U.S. asylum system despite HARP and other initiatives aimed at blocking them. Still, though “there will be cracks in the system,” an El Paso-based service provider voiced certainty that migration “won’t go back to the wave of 2019”—at least not next year.

Whatever happens, little of it will play out on U.S. soil. At least as long as court challenges remain unresolved, programs like Remain in Mexico, metering, the July 16 ban, and “safe third country” agreements will push asylum seekers elsewhere. This will make their plight—falling victim to crime, illness, and “refoulement”—less visible to U.S. citizens, who were so outraged by family separations and accounts of “children in cages” when they happened on U.S. soil.

The new complexity blunts popular outrage and will to engage in activism.“So many people want to help out, but now it [the problem] is all in Juárez now,” said a service provider in El Paso. “They’re like, ‘where did they [the migrants] all go?’ Other narratives come up, and public opinion gets complicated. These programs are opaque by design. We stress that this is still the same ‘deterrence through cruelty,’ but that doesn’t leave people confident to have an opinion and share it. So you don’t have ‘ambassadors.’”

That comment’s tone of resignation was something we heard repeatedly. It was probably the most serious concern we took away from this part of the border.

The children’s television host Fred Rogers famously said that when kids see troubling or frightening things on the news, they should “look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” In El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, there are many helpers. But most of the helpers we talked to are in a deep state of exhaustion.

Among our 15 interviews, a few subjects were animatedly angry, but most spoke in monotone, many staring into the middle distance. “In 21 years, I’ve never seen a year and a half like this. So many evil things at the same time,” said an organization’s director. “I can’t believe what’s happening—what we’re becoming,” said a service provider.

“The response on both sides of the border sits on the backs of underpaid ‘border warriors,’” said an international organization representative. “But they’re falling apart. Exhausted. They have so much secondary trauma.” One group doing pro-bono asylum representation has had two attorneys hospitalized this year for stress-related injuries. “There’s no time to eat or drink, you’re on the bridge for hours trying to get back home,” said the director. Blanca Navarrete of Derechos Humanos Integrales en Acción lamented having to keep up with the demands of running virtually the only organization in Ciudad Juárez doing human rights work. “We probably do have PTSD,” added an El Paso NGO director. “Sometimes we organize something around children dying or similar, and the organizers can’t even talk, they just cry.”

Beyond just a bit of time off, organizations said that their greatest need is more personnel to share the mission: paid staff, not just volunteers. Attorneys with clients stuck in Juárez also said they need office space on the other side of the border.

Whether one regards them as “helpers” or not, Border Patrol agents, too, sounded exhausted and—though they didn’t say so explicitly—unsupported by their top management. They started the year going nearly two months without pay during the government shutdown. Then, they spent months performing childcare and administrative tasks that few were prepared for, with paltry resources and insufficient guidance. The subhuman conditions in facilities like the Clint station were stressful for most of them, too. Once that situation began getting mass news coverage, agents said they felt keenly aware of dirty looks and cold receptions when out in public spaces. Attitudes improved a bit, they said, after the response to the August mass shooting in an El Paso Wal-Mart fostered a citywide sense of unity.

From the family and child migrant influx to the Wal-Mart attack, from Juárez’s homicide spike to the severe erosion of asylum, 2019 was a very bad year for this part of the border. While 2020 is difficult to foresee, it’s hard to conclude that help is on the way.

Still, at some point in the next few years, another migrant wave is almost certain to come. When it does, what El Paso and Ciudad Juárez have endured this year should help to build a better response.

This would mean altering the framing and language: “It’s toxic,” said García of the BNHR. “We need to stop talking about ‘border security’ and talk about border management, border governance, border safety.”

It would mean looking beyond asylum to consider taking in even more people as Central America’s meltdown continues. “Some children have arrived with distended bellies and their hair coming out by the handful,” said a humanitarian worker. “It’s not just asylum, it’s ‘my kids will die.’ But there is nothing in asylum law to protect them. The 80 percent denial rate needs to be 50.”

It would mean separating immigration and border security into two separate tracks handled by different parts of the government, so that migration can be managed and any security threats can receive proper focus. “Migration muddles that up,” García noted.

In El Paso and elsewhere, the trauma that the Trump administration is fostering, and the way that the “helpers” respond, promise to resonate well beyond the U.S.-Mexico border zone. “Our southern border is the new Ellis Island of our age,” reads a document from the BNHR. In his El Paso office, García posed this as a question. “Is the border going to be a new Ellis Island, or a national security threat? This is where the character of the nation will be defined, the ideal of America, for the next 50 years.”

The outcome is uncertain.

The author thanks WOLA board member Patricia Weiss Fagen for accompanying and supporting this field research visit.