A version of this project was originally published in Spanish by Colectivo Linea 84.

“To see what you want to see will take us a while,” Iván tells me just in front of his house. “That stone that you are looking for is already cast out into the sea.”

Iván is a tiny, thin fisherman who was born and lives in Barra del Motagua, a community in the northern Honduran municipality of Omoa, perched at the border with Guatemala. He has agreed to guide me and Marcos, a young biologist from nearby Cuyamel, to see the obelisk-shaped landmark that draws the boundary between Honduras and Guatemala. The challenge is that the obelisk—or what’s left of it—is sinking.

The fisherman looks at me with doubt. The burdens and misfortunes that he has long fought seem to now colonize his facial expressions, banishing him to some corner of himself where he waits for something or someone to call him back. Iván’s house is barely standing. His community and neighboring Barra de Cuyamel are being swallowed up by the sea.

The tide has been encroaching on these communities, as well as their houses, croplands, and water sources, for the past 10 years. The situation is increasingly driving locals to flee, leaving behind a ghostly border. The devastation brought by Hurricanes Eta and Iota, the strongest to hit the Atlantic this year, exacerbate this grim picture—haunting warnings of what climate change is set to bring to this vulnerable region.

The strange and desolate beach stretches for miles. We walk past vegetation buried in the sand, dry palm trees, dead mangroves, and lots of trash, which the rivers and tides manage to carry here from as far away as Guatemala City.

Parts of some of the houses in these two communities are already under water. Iván says many residents have already left. Some have headed further inland to rent homes in Cuyamel, but “most of them went to the United States,” he explains. There’s mostly one reason: “The sea took them out.”

Biologist Gustavo Cabrera, who has worked in the area for years, had offered a sobering assessment. “The sea keeps gaining ground,” he told me during an interview the day before I met Iván. “It has already swallowed 70-80 percent of the towns of Barra de Cuyamel and Barra del Motagua. A kilometer of coastline has been lost in less than 10 years.”

The Sea Came Here to Stay

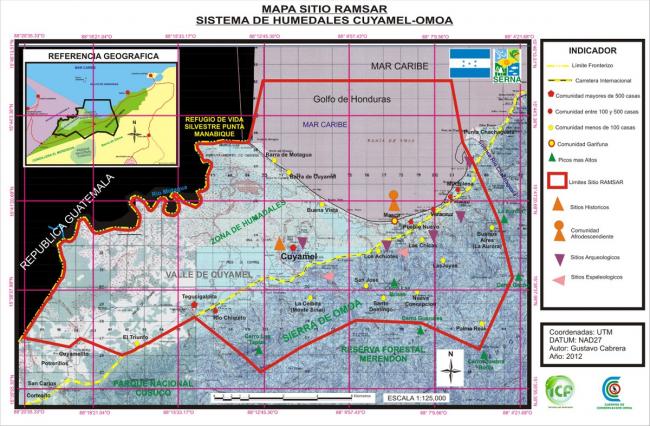

Barra del Motagua and Barra de Cuyamel are located inside the National Park Cuyamel-Omoa (PANACO), which the government officially declared a protected area in 2011. The wetland system inside PANACO’s specially protected core area is fundamental for the preservation of the second most important coral reef system in the world, known as the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (MBRS). In 2013, the international Convention on Wetlands, also known as the Ramsar Convention, declared PANACO a site of international importance.

The wetland ecosystems and water sources are also key for the daily survival of the surrounding communities.

According to the government’s Cuyamel-Omoa Biophysical Diagnosis of 2017, there are four reasons why the sea is invading the Omoa coast: Rising sea levels as a result of climate change, coastline changes due to the construction of infrastructure like embankments, the change of course of the Motagua River as a result of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, and the collapse and disfigurement of agricultural and residential lands due to a 2009 earthquake. The earthquake accelerated the sea level advancement already underway. As a result, according to the diagnosis, “it is presumed that the communities remained below sea level, facilitating the invasion of waters into continental soil and also the intrusion of seawater in extensive cultivation areas.”

Nowhere to Go

The path to the obelisk is long. The entire beach is infested with little insects that bite at the speed of a machine gun: gnats. As we walk, the gnats escorting us, Iván explains what the area looked like before the salty water took over. There was an estuary, mangrove, fish in these habitats, houses, arable land, and more people. Like the mangrove and the vegetation, the community is disappearing.

A 2017 report by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation titled Justice and Climate Change in Honduras mentions possible relocation for residents in areas like Omoa. The issue has been on the table for years. According to the study, the Omoa mayor’s office had identified a piece of land to relocate the families from these two communities at least three years ago. But the land was privately owned, and “the people of the community couldn’t afford and the municipality resisted paying” the asking price of 3 million lempiras, $119,520. Omoa mayor Ricardo Alvarado, who has now been in office for more than a decade, told Honduran media outlet Contra Corriente in 2018 that the municipality had a plot of land in a nearby town to accommodate the relocation of 80 families. However, authorities declared the areas of Barra del Motagua y la Barra de Cuyamel where these families live uninhabitable in 2012, and government responses to the emergency have been slow.

At the beginning of 2020, heavy rains hit the Gulf of Honduras in the Caribbean, which put all the communities along the Atlantic coast area on alert, including the communities in Omoa. Although authorities announced the evacuation of Barra de Cuyamel and Barra del Motagua, some families did not leave because, to date, the relocation plans remain temporary.

I ask Iván if he would consider relocating. “Relocate? Not really,” he says. Despite talk from the mayor’s office about such plans, he says, it’s unclear what relocation would look like, and where residents would go. “I think it’s going to be near Cuyamel...something like that,” Iván continues. “That’s what I’ve heard the mayor say...he says sometimes to one place, then to another place and...” Iván keeps talking, but an absurd tedium takes over.

After clambering into Iván’s canoe, we ride as far as we can towards the border through a small river. But we get to a fence that blocks our way. It is private property, Iván says, looking at me, his words dry. It belongs to the palmeros—the owners of oil palm plantations. Before I can ask more questions, the canoe jerks as the biologist tries to stand up. Iván shouts at him to sit. As we rock, I see on the other side of the barbed wire some houses that are still standing. But they, too, will be swallowed up.

The Palm Plantations Took Root

Since 2006, Honduran agricultural export policy has focused on oil palm plantations, with plans to expand cultivation by 28,000 hectares focusing on four departments: Yoro, Atlántida, Colón, and Cortés, where PANACO is located. Palm oil is used in the production of processed foods and as biodiesel, which is part of international “clean energy” schemes. Palm blankets large swathes of land along Honduras’s north coast and has also encroached on PANACO. Beyond the relentless advancement of the sea in the area, palm monocultures are driving the destruction of natural resources, including in this protected area. Oil palm expansion also aggravates social conflicts and has been linked to human rights abuses and assassinations of social leaders in Honduras and other countries.

In the Omoa wetlands, communities are squeezed between oil palm—associated with land grabbing, ecological disaster, migration, and at times drug trafficking—and the rising sea.

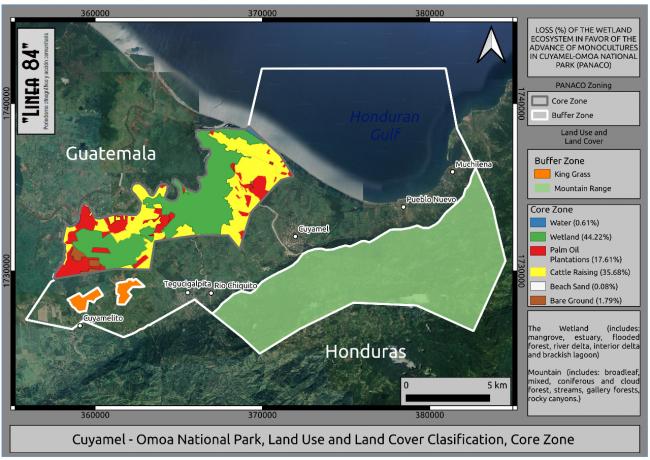

Protected areas such as PANACO are divided into a core zone and a buffer zone. In theory, according to the PANACO management plan, the core zone is destined for absolute conservation. In other words, no deforestation, no diverting the course of the rivers, no modification or alteration of the area, and definitely no palm plantations.

The wetlands are crucial to maintain the balance between saltwater, fresh water, the reproduction of edible fish, and the barrier reef that provides economic sustenance not only in Omoa, but also in other areas across Mexico and Central America.

This map, elaborated with Sentinel 2 images from the European Space Agency (ESA), shows that palm covers 17.1 percent of the wetland area in the core zone and that only 44.22 percent of the wetland remains. Cattle ranching, which occupies 35.68 percent of the core zone, is one way of introducing palm. Diverting the course of the rivers to flatten the land and deforest it is a common practice in cattle ranching, which serves as a precursor for cultivating plantations can be cultivated after grazing cattle. Thus, palm gains ground, just as the sea.

As the Friedrich Ebert Foundation’s 2017 climate justice study highlights, one of the main problems to overcome in addressing climate change is the worldview that sees natural resources and the environment as commodities, and this approach is ubiquitous in Honduran environmental and development policy. The influence of the United States and its mercantilist vision of resources and the environment is particularly present in the government’s Country Vision 2010-2038 and National Plan 2010-2022. According to the report, these documents offer “a clone” of the Sustainable Territorial Development plan prepared by the Center for Economic and Social Research of the country’s largest business lobby, the Honduran Council of Private Enterprise (COHEP), which is funded by USAID.

PANACO, its sea, its palms, and all the stories behind its destruction are part of the catastrophic consequences of climate change that are already underway. According to a 2008 study by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), refugees from climate change will number 200 million by 2050.

Haunting the Border

At the border, I finally glimpse the obelisk. Iván says it used to be inland, where its base sat in the waters of the estuary. But when the sea advanced, it dug up the marker and broke it. Now the base is uncovered, and it looks like a mangrove with its roots outside, in the open, abandoned and waiting for the sea to swallow it.

In her 2008 book Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, sociologist Avery Gordon links haunting to social violence. She writes: “Haunting is one way in which abusive systems of power make themselves known and their impacts felt in everyday life…What is distinctive about haunting is that it is an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely…[G]hosts appear when the trouble they represent and symptomize is no longer being contained or repressed or blocked from view.”

Indeed, Iván says that he only gets scared when the sea is angry, when it knocks on his door and wants to come in. He laughs nervously at a reality that seeps like the saltwater under the foundations of his house and dampens the walls.

This ghostly border offers a haunting warning. The sea was only the trigger, unleashing the consequences of a capitalism without borders. The flooding provoked by Eta and Iota in inland and coastal communities of Honduras this year and the advance of the sea, palm, and migration are the products of that system. In the end, the ghost of the border will come knocking at our doors, just as the angry sea knocks at Iván’s.

Areli Palomo Contreras is based in Mexico and is the co-founder and main writer at Linea 84 Collective, ethnographic journalism and community action. Areli has a remarkable field research background and knowledge on the topic of Central American migration crossing Mexico towards the United States. She is committed to initiatives and actions that lead towards a public critical understanding on how global political economy engenders migration flows.