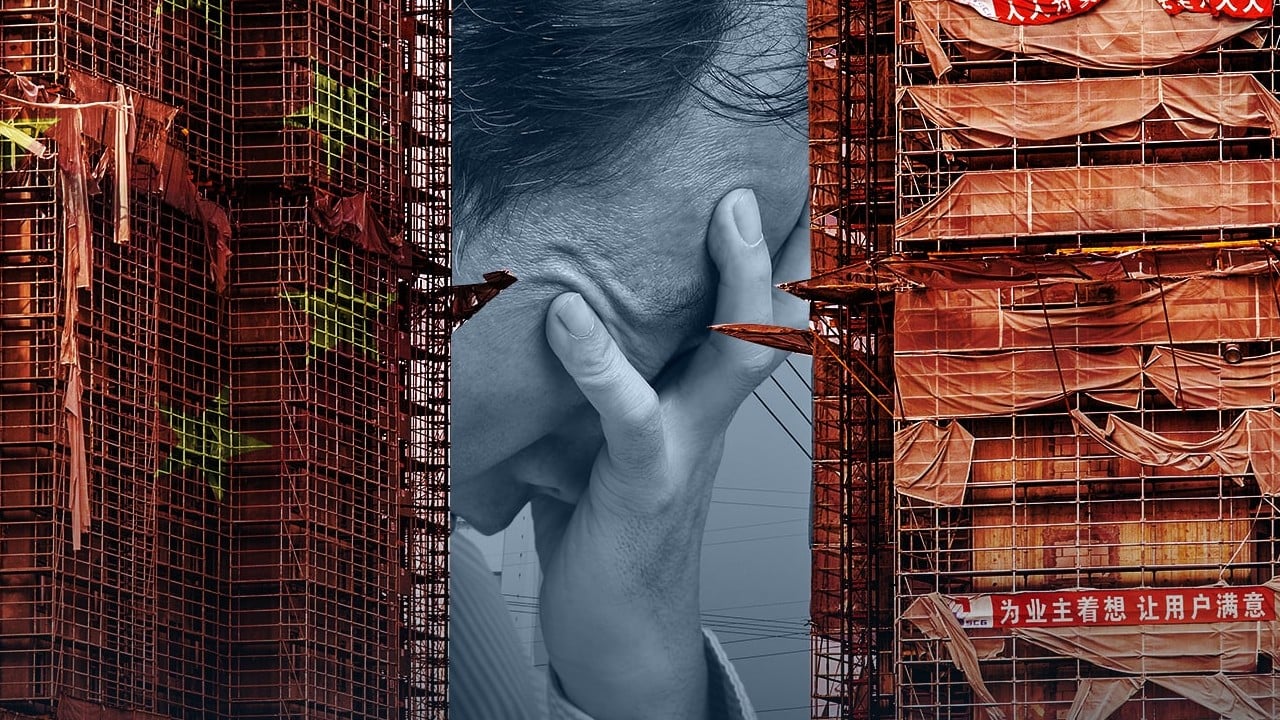

Can China’s second-gen factory owners give ‘made in China’ a second chance in crisis?

- Like young monarchs, suddenly thrust at the helm of their family’s legacy, Gen Z and millennials are returning to oversee decades of business growth in difficult times

- The generation that made China a manufacturing powerhouse is being aged off the job, heaping responsibilities on often-unprepared offspring – but their fresh ideas may just save the industry

After bouncing between multiple jobs – from furniture sales to e-commerce – for a decade, Rachel He decided to go home in 2021 and take over a 30-year-old factory founded by her father.

The major reason for her return was that her parents are in their sixties, and their waning health no longer allowed them to fully commit to the daily operation of a factory with around 50 workers.

“I’m their only child. If I don’t go back, is the factory really going to be shut down?” said the 34-year-old. “Then what about those employees who have been following my dad for over 10 or 20 years?”

Located in Foshan, Guangdong, He’s factory is part of the local industrial cluster specialising in aluminium plating – an indispensable construction material used for ceilings in office buildings and escalators in malls.

But before she officially became the new boss, she knew very little about the industry and had no idea how to operate a factory or navigate its litany of priorities, from taxes to recruitment. And now, two years into the gig, He faces the challenges that come with a significant economic slowdown, and she is trying to balance that with frequent trips to see her father at the hospital.

‘Intensified, decelerated, cooled’: 4 takeaways from China’s July activity data

“Sometimes I would get so tired, so confused, and I didn’t know what to do,” she said. “Then I would just send a message to the chat group to ask, like how to hire new people, how to manage, and even how to safely pull out in case the factory really can’t keep going any more.”

The chat group He relies on comprises hundreds of “Changerdai”, or second-generation factory owners, like herself. Based all over the country and spanning all imaginable manufacturing sectors, these millennials and even members of Gen Z have been connecting with each other via online posts since “Changerdai” started trending earlier this year.

Their parents had carved out similar paths to success. Coming from humble backgrounds, they rode China’s golden times of unprecedented economic growth, profiting from the booming real estate sector, rapid urbanisation and the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization. At the same time, their facilities – usually small in size – were also the mainstay of the country’s rise to the “world’s factory” and the second-largest economy.

After three decades, when it comes to intergenerational inheritance, their children – internet savvy and often with an overseas education background – are able to stand on a higher starting point. But the preferential macro environment has long gone – replaced by a slumping property sector, a slowing domestic economy, a relocating global supply chain, fiercer competition from other developing countries, and rising geopolitical tensions.

Still, as the burden of the factories falls onto the shoulders of the second generation, that also makes them responsible for the future of “Made in China”. Whether it can continue to thrive and even survive is up to them.

As office vacancy rates have continued to rise in major Chinese cities, and new infrastructure projects have remained suppressed since the pandemic, He was not remotely optimistic for her factory’s business prospects.

Now in Guangdong, when a new construction project comes out, hundreds of factories like He’s compete for it, regardless of whether it’s even that profitable, she said.

“As my dad always says, the time when you can make a big fortune in this industry has long gone,” she lamented.

The dim future inevitably makes her think of quitting, but it’s not a really viable choice when she considers the workers – many of whom watched her grow up – and the importance of the factory.

“Now it is hard to find another job for people their age,” He said. “I can’t just simply abandon them.”

It’s easy to conquer a territory, but hard to guard it

The property downturn has hit Zheng Shijie equally hard. In 2019, he officially took over a manufacturing plant in Wuhan, Hubei province, from his uncle. Producing power-distribution equipment used in all scenarios that need electricity, the factory has an annual industrial output value of close to 20 million yuan (US$2.78 million).

But now, the accounts receivable on the factory’s balance sheet total almost 10 million yuan – accumulated from several real estate companies since the country’s widespread property-sector crisis unfolded in 2021.

“We are a sunset industry. The whole market is in decline,” the 30-year-old said.

Another major source of revenue for his business comes from municipal projects, but the money from these is also shrinking as local governments – which heavily rely on land-sale revenue – become increasingly cash-strapped.

Due to mounting cash flow pressure, several peers of Zheng have recently quit the industry – a sharp contrast with times when earlier generations rushed to enter it.

“It feels exactly like the [Chinese] saying, ‘It’s easy to conquer a territory, but hard to guard it,’” Zheng said.

China’s factory activity fell back to contraction in July: Caixin PMI

For export-oriented manufacturers, the market this year is no better than that for those in the property upper stream, as a global economic slowdown has suppressed the overseas demand for Chinese products, on top of an accelerating trend of Western countries – especially the United States – diversifying China-centric supply chains.

The trend is especially evident for the apparel industry, as US fashion companies are seriously reducing their “China exposure” and moving sourcing orders to China’s competitors in Asia, according to Sheng Lu, an associate professor with the Department of Fashion & Apparel Studies at the University of Delaware.

In the first five months of 2023, measured in value, the share of US apparel imports from China fell to 18.3 per cent, compared with nearly 30 per cent in 2019, according to figures from the Office of Textiles and Apparel under the US Department of Commerce.

Meanwhile, the share of total imports from Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, and Cambodia reached a new high of 44.3 per cent, up from 37.1 per cent in 2019.

For 27-year-old Jenny Jiao, the figures reflect an urgency for her to grow up quickly to share her family’s burden.

After obtaining a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University and briefly working in finance, Jiao decided to go back to her father’s casual-suits factory based in Liaoning province late last year, shortly before a trade company sourcing for the US market broke the contract to buy around 200,000 suits a year – for which her father had specifically built a new facility and hired 200 more workers.

“The trade company said that if they don’t shift the sourcing to Cambodia, their clients in the US would terminate the collaboration with them,” Jiao said.

With lost orders and heavy loans for the new facility, Jiao felt the pressure on her shoulders quickly piling up – if the loan can’t be repaid, it means the painstaking efforts of her dad in the past two decades would end in vain.

“Honestly, in the next five or six years, it will be a success as long as we can survive.”

Recently, Jiao and his father have settled on a clear division of labour: the father continues to focus on the daily management of the two apparel plants, so that the daughter can be given the luxury to try something new.

So far, the trials include reaching out to foreign brands directly – skipping the trade companies in between, and expanding domestic market exposure by promoting on Xiaohongshu – a lifestyle app popular with Chinese youth.

Meanwhile, through taking costume design courses, she is working on bringing in independent design – from pattern making to material procurement – as opposed to the old mode of contract manufacturing in which the factories simply follow the demand of downstream clients and process using the materials provided.

“Every direction has its own hurdles,” Jiao said. “Ultimately, I just want to sell more clothes and bring back more orders. I don’t want the factories to end up closing their doors on my watch.”

Aside from bringing their business out of an economic dilemma amid rising external uncertainties, most second-generation factory owners are also desperate to prove themselves, especially to their parents and more experienced long-time employees who may still regard them as children.

“In small companies like ours, whomever gets the new orders is qualified as the boss,” said He from Foshan. “Before you bring back real orders, no one respects you.”

‘It’s a tricky time’: firms adjust to new reality as China pull-out intensifies

Even though she has officially taken over the factory, old resources and clients established by the older generation cannot simply be inherited. She needs to strive to secure her own new clients.

“In fact, I don’t think we are Changerdai, but first-generation entrepreneurs,” He said.

For many traditional manufacturing sectors with scarce technological innovation involved, keeping the price down is always the silver bullet in gaining market share, but many are also looking to reform and upgrade.

Such a decision, however, is never easy to make. For smaller manufacturers, with their weaker ability to resist risks, the cost of trial and error is much higher.

Zheng, the power-distribution equipment producer in Wuhan, had thought of riding the wave of green energy and shifting to products like electric-vehicle charging piles, but in the end decided to maintain the status quo while continuing to assess a possible shift.

“Transformation means more risks and challenges. The overall economic condition is not good now, and we have a very tight cash flow,” he said. “Shifting to a new product means much more fixed expenses such as for new equipment in the very early stages. The pressure can be very high.”

Times have changed. How can we just spin our wheels?

Before Kitty Pan went back in 2019, her father’s factory producing spa-pedicure chairs and shampoo stations for salons were on the cusp of collapse: it was bleeding cash after rounds of price wars with peers in the domestic market and could barely afford to pay its employees.

“I felt that if [low-price competition] continued, there was not going to be any way out,” said the 29-year-old Foshan native. “So, I thought, why not go in the opposite direction – by focusing more on quality rather than price.”

The real turning point came when she attended a beauty trade show in South Korea that year, where she managed to settle a long-term contract with a client who was also searching for a stable supply of shampoo stations.

Thanks to the order, the factory’s operations have stabilised despite the three-year pandemic. As more new overseas clients were developed, exports now account for 80 per cent of the factory’s overall business, and the firm was recognised late last year as a “hi-tech enterprise” by the local government.

“I felt like there are always more solutions than problems,” Pan said. “Times have changed. How can we just spin our wheels?”

Skilled manpower and hi-tech: what’s the outlook when China is short of both?

Unlike Pan, who took over a teetering factory, 27-year-old Gloria Liang was luckier when she joined her father’s metal-plate-processing factory last year, as it has a stable customer base with an annual turnover in the tens of millions of yuan.

But Liang was not satisfied with the status quo, and believed she must bring new blood to the company that had inevitably been impacted by the property slump.

“Right now, regardless of products, the whole manufacturing sector can’t escape the rat race, as the information gap is closing,” Liang said.

With a master’s degree in innovation and entrepreneurship from the University of Bristol, she started out by promoting the factory and its products on social media. Within months, she has become one of the most popular influencers on Xiaohongshu representing the young factory community, thanks to which she has also expanded the company’s custom stainless-steel-furniture business by attracting customers online.

Compared with her father’s generation, which was more fixated on sales figures, Liang believed the future competitiveness of a factory relies on innovation – that is, hi-tech products and refined services that can’t be easily duplicated.

“We don’t want to do just manufacturing, but smart manufacturing,” Liang said.

Also having studied overseas, and at the age of 27, Sun Chuanzhen has been looking to promote his father’s chemical-adhesive products online to attract foreign buyers instead.

Unlike other traditional manufacturing sectors, China’s fast-growing chemical industry, which has been the largest in the world by revenue since 2011, has largely stayed intact from the ongoing global industrial chain relocation, as cost pressures for chemicals are significant and the country is the world’s biggest chemical consumer.

Still, Sun has made plans to dedicate more efforts to developing more advanced and environmentally friendly adhesive formulations since returning to the Shandong-based factory in January, as both China and the rest of the world are tightening up environmental requirements for the industry.

By copying advanced experiences and undertaking the transfer of production capacity from the West, China’s chemical industry has accumulated around three decades of technical, capital and talent reserves, but that does not mean its status is unshakeable, Sun added.

“What is the problem now? That is, some emerging countries, like those in Southeast Asia, Latin America and even Africa, also want to build their own chemical industries. So, they are like China 20 years ago,” he said. “If we don’t take a step forward, we will surely be replaced by them. And this is the crisis of China’s manufacturing sector.

“So, we should continue to develop better products based on existing advantages, making them unable to catch up.”