Medicaid expansion is not just a moral imperative — it could provide a much-needed tonic for the fiscal ailments that many rural hospitals face in North Carolina.

Legislative leaders’ refusal to expand Medicaid has deprived hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians of lifesaving medical care and has left rural hospitals dangling in the fiscal winds. As has happened in many states where Medicaid expansion has been blocked by a hardened ideological agenda, rural hospitals in North Carolina are struggling to cope with a number of pressures, including high uninsured rates and uncompensated care costs.1 Seventy of North Carolina’s 80 rural counties are already designated as “medical deserts” for their lack of primary care availability2 and, if the General Assembly doesn’t pass Medicaid expansion this year, even more rural communities stand to lose their primary provider of critical health services.

This report details how full Medicaid expansion would shore up rural hospitals’ finances and why saving rural hospitals is essential to the long-term economic vitality of many communities in North Carolina.

Medicaid expansion would stabilize hospitals and improve access to health care

Medicaid expansion represents the most immediate and cost-effective way to stabilize rural hospital finances and expand coverage for North Carolinians. The effectiveness of Medicaid expansion in stabilizing rural hospitals has been dramatically borne out over the past several years, as the overwhelming majority of rural hospitals forced to close their doors were in states that have not expanded eligibility.

Across the country, more than 80 percent of the rural hospital closures since 2010 have occurred in the handful of states that have not implemented Medicaid expansion.3 North Carolina has sadly been part of this story, with five hospitals closing over that same time. Some of these hospitals could still be open today if leaders in the legislature had not stood in the way. Against this backdrop, the next section reviews current projections of how Medicaid expansion would increase coverage and bolster hospital finances.

Expansion would bolster rural hospital finances

Analysis provided by a member of the North Carolina General Assembly indicates that expanding Medicaid would benefit nearly every hospital in the state. North Carolina hospitals would collectively see hundreds of millions of dollars in net new annual revenue, and hundreds of thousands of people would gain access to affordable health coverage.

Once fully phased in, the legislative analysis projects that Medicaid expansion could provide affordable coverage for up to 650,000 people and generate more than $1.8 billion annually in hospital reimbursements. Even while covering the state’s share of the costs, hospitals would see a nearly $400 million net improvement in their financial standing. Preliminary estimates produced at the individual hospital level are provided in the Appendix.

Rural hospitals stand to see a substantial share of the financial benefits

Based on the UNC Sheps Center definition,4 rural hospitals would receive approximately $665 million in new Medicaid payments each year, which would improve rural hospitals’ net fiscal strength by nearly $140 million.

The benefits of Medicaid expansion to people’s health and well-being and, in turn, to the broader community would be thwarted by the erection of barriers to health care for those in the coverage gap. While estimates produced by a N.C. legislator suggest that hospitals could experience greater gains to their bottom lines, long-term improvements to health and the conditions under which hospitals operate would be hampered.

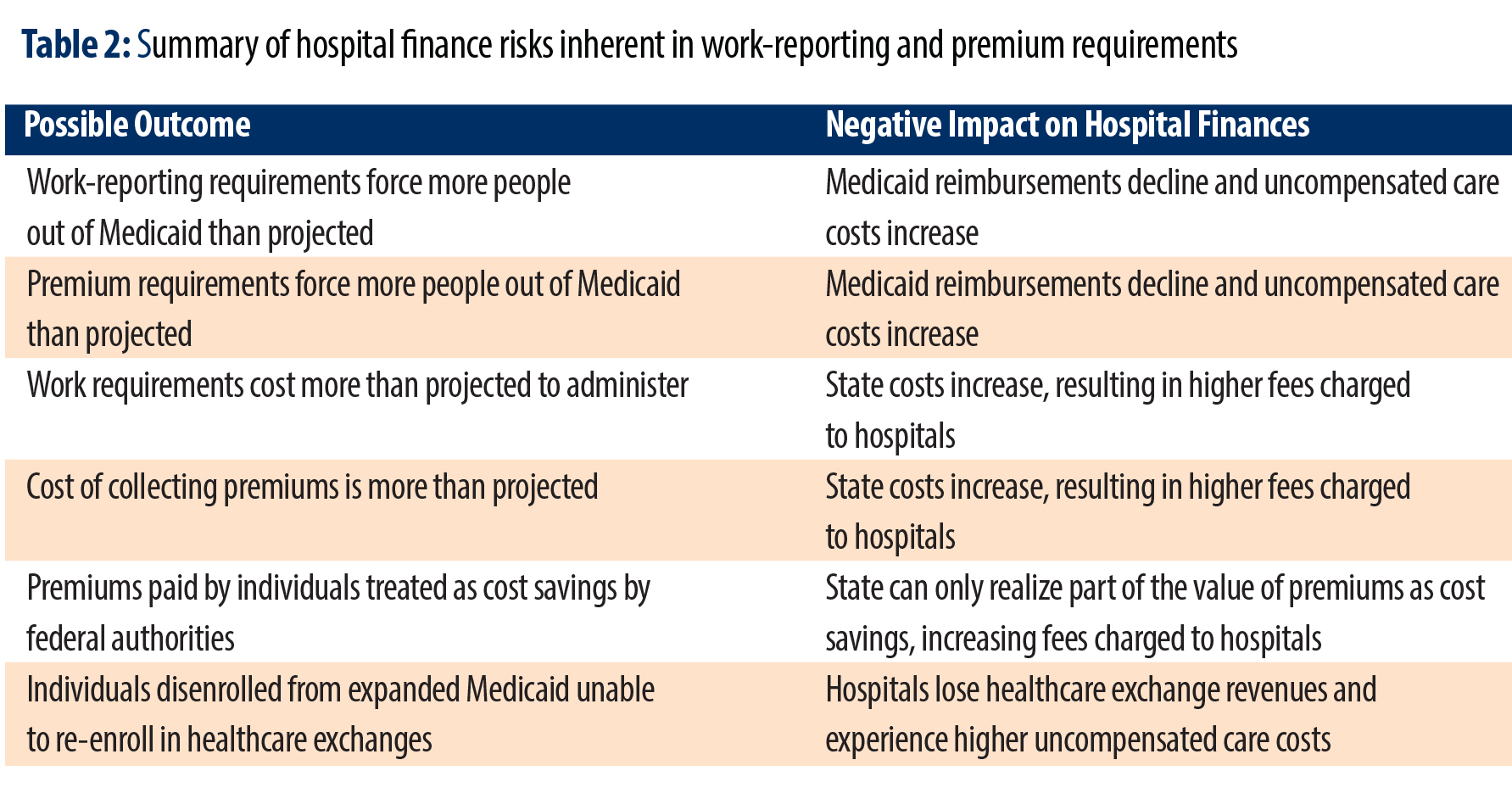

In addition, a host of challenges bedevil the process of predicting how restricting access to health care would affect those in the coverage gap and the financial impact on North Carolina’s hospitals. Analysis provided by a member of the North Carolina General Assembly of House Bill (HB) 766 — which includes two such barriers (monthly work-reporting requirements and premiums) — indicates the bill would have a larger net fiscal benefit for North Carolina’s hospitals by $52 million, 13 percent higher than the net fiscal impact of full expansion by our analysis. However, a range of uncertainty around key factors could dramatically change that modest difference. The next section outlines a variety of risks inherent in requiring work reporting and premium payments that could decrease the fiscal boost that Medicaid expansion would provide for rural hospitals in our state.

House Bill 655, NC Healthcare for Working Families

HB 655, a bill to close the coverage gap, was introduced in the 2019 Legislative Session. While the bill would expand Medicaid eligibility to several hundred thousand individuals across the state as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), it includes harmful provisions that would make it extremely difficult for many low-income and working North Carolinians to qualify for the high quality, affordable health coverage they need. Specifically, it would take coverage away from individuals living near or below poverty if they:

- Do not report at least 80 hours of work or volunteer activities in a month

- Do not pay a monthly premium of 2 percent of their income

Why work reporting and premiums could decrease health coverage and undermine hospital finances

While it is impossible to precisely predict how many North Carolinians would likely lose coverage and how the practicalities of implementation would affect hospitals’ finances, the specific provisions of HB 655 would prevent North Carolinians from getting coverage and could in turn reduce the financial benefit for the state’s hospitals. To date, the policy debate and evaluation process has not generated a consensus view of how the provisions of HB 655 could undermine the goal of Medicaid expansion or the likelihood of different risks manifesting themselves during an implementation process. National researchers and observers of variations on these provisions and other barriers have found their implementation to dramatically reduce enrollment, undermining the purpose of Medicaid and the benefits to rural hospitals.5

Work requirements could result in larger coverage losses and greater harm to hospitals

HB 655 would require many North Carolinians to meet and report a minimum number of hours worked each month or risk losing their Medicaid coverage. Legislative projections assume work requirements would decrease Medicaid participation by nearly 35,000 (7 percent), but there are reasons for concern that work requirements in HB 655 could actually result in a significantly higher rate of coverage loss.

A similar restriction implemented in Arkansas resulted in 23 percent of people subject to work-reporting requirements losing coverage, which is substantially higher than the rate of coverage loss in legislative analysis provided by a member of the North Carolina general assembly. Lack of access to stable employment and the complexities of reporting hours worked led a large number of Arkansans, many of whom actually met the minimum threshold for hours work, to lose coverage. It is impossible to precisely predict how many North Carolinians would lose coverage under HB 655 compared to full expansion because a great deal will hinge on how these limitations are implemented and enforced. However, if the level of coverage loss experienced in Arkansas were to take place here, 88,000 North Carolinians could find themselves without health coverage.6

Larger than projected coverage losses will undermine the financial benefits of Medicaid expansion as hospitals will continue to face uncompensated care costs that would otherwise be covered.

Premium requirements could result in larger coverage losses and greater harm to hospitals

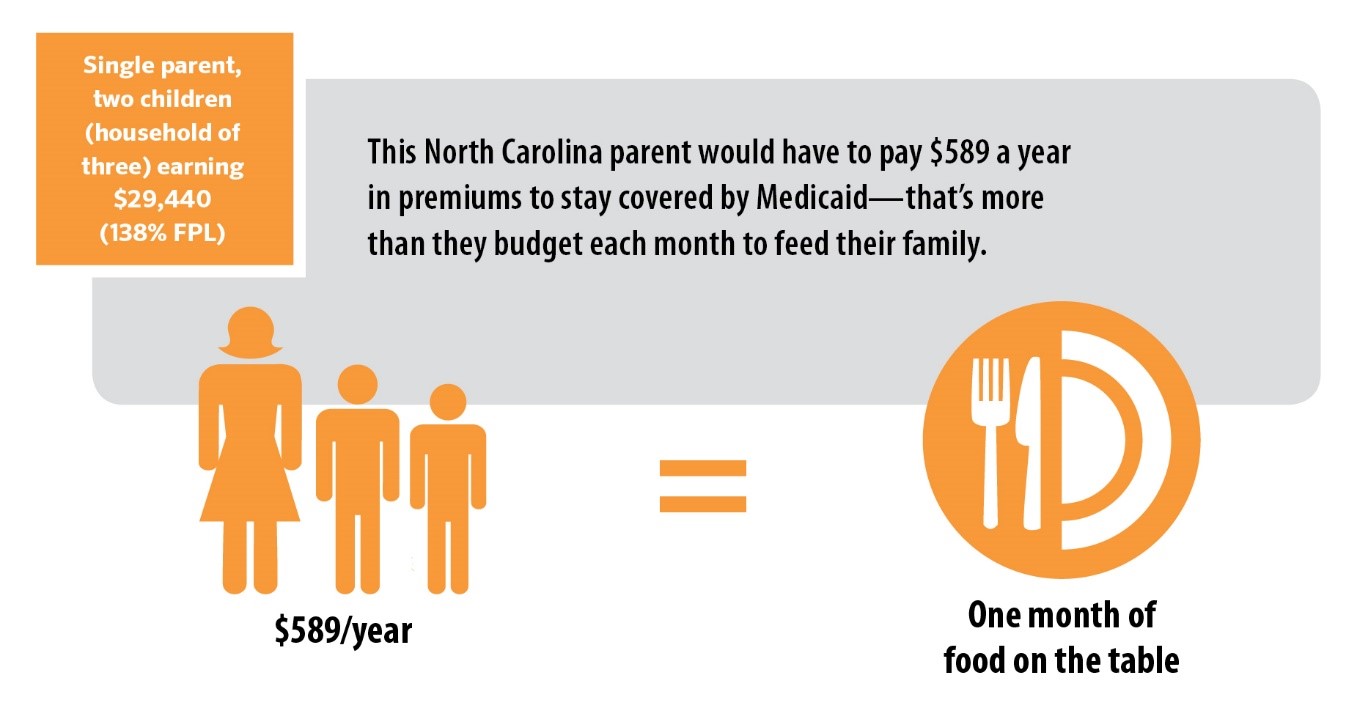

A similar risk is present with premium payment requirements. HB 655 would require many potential Medicaid enrollees to pay 2 percent of their annual income to participate in the program. For a single parent with two children earning 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level ($29,440), this would equate to paying nearly $600 over the course of a year, or roughly that family’s food budget for an entire month.7

When Indiana imposed a similar requirement as part of Medicaid expansion, it forced people out of the program or prevented them from ever enrolling in the first place. Analysis provided by a member of the North Carolina General Assembly assumes that premium requirements could push over 38,000 North Carolinians out of the program, but it’s possible that coverage losses could be substantially higher. In Indiana, premium requirements resulted in nearly 30 percent of potential Medicaid beneficiaries subject to the requirement losing coverage, which would translate into roughly 145,000 North Carolinians being pushed out of the program if the same level of coverage loss were to take place here.

Coverage losses like those experienced in Indiana would dramatically undermine the fiscal benefits of Medicaid expansion to rural hospitals. Just as with work requirements, pushing down enrollment through premium requirements would reduce the new reimbursements that hospitals receive and force them to cover more of the costs of providing care to uninsured patients.

Work-reporting requirements would increase state and county administrative costs

Work-reporting requirements would be complicated and expensive for agencies tasked with implementation. Many of the complexities of implementation have not been nailed down, so the real administrative costs could greatly exceed those assumed in projections reported here.

Current analysis at the county level can only incorporate the number of Medicaid enrollees, resulting in a lower projected cost for HB 655 than full expansion because fewer people would be able to participate in the program. However, experience from other programs that have implemented work-reporting requirements underscores just how complicated and expensive the enterprise quickly becomes. North Carolina has implemented work reporting for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) and Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) in the past, and in both cases, the change necessitated the development of costly new tracking technology and required extensive training for county employees.

Even though some administrative costs would be covered with federal Medicaid funds, state and county agencies would be forced to carry part of the burden. For county agencies with limited resources, these new costs would make implementation deeply challenging and could actually result in lower levels of services for other programs. Any state costs that exceed what has been estimated to date would likely be passed along to hospitals in the form of increased hospital assessments, reducing the net fiscal benefits of Medicaid expansion.

Premiums could cost more to administer than would be collected

Implementing premiums could actually cost the state more to administer than would be collected in the first place. To date, analyses of HB 655 count the revenues collected through premiums as a cost saving to the state, which translate into lower hospital assessments — but the real costs of collecting these premiums could be far higher than currently projected.

Evidence from other states indicates that premiums could actually turn out to be a net fiscal loss once the administrative costs are considered. Virginia used to require participants in the Children’s Health Insurance Program to pay a $15 monthly premium per child for families between 150 and 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. However, that policy was discontinued once it became clear the requirement led to substantial loss of coverage and cost nearly $1.40 to administer for every $1 in premiums collected.8 Analysis of a proposed premium payment requirement in Arizona indicated that it could cost the state four times as much to administer the policy than would be collected, even if the state charged the maximum level of premiums permitted.9

Particularly given that North Carolina would likely have to build an entirely new system to collect premiums and identify people who would be disenrolled for non-payment, the cost is likely to be substantial. Cost overruns would likely be passed along to hospitals in the form of increased hospital assessments, decreasing the financial benefits of HB 655 in comparison to full expansion.

State may have to share premiums collected with the federal government

Current projections assume that the full amount of premium payments made by individuals can be put toward the state’s 10 percent share of the cost of services for the program. In addition to concerns about the administrative costs of collecting premiums, there is significant risk that federal authorities will deem these premiums to be a form of cost savings to the program,10 which would severely limit the amount of premiums that can be used to pay for the North Carolina’s share of Medicaid expansion. If premiums collected are treated as cost savings, the federal government could be entitled to capture 90 percent of the value, consistent with its enhanced match for Medicaid expansion, leaving only 10 percent of the value of premiums for North Carolina to use to pay for its share of expansion costs. This would require higher hospital assessments than are incorporated into current estimates, reducing the net fiscal benefit of expansion to hospitals.

Hospitals could lose some revenue currently provided through existing insurance coverage

Participants who lose coverage under expanded Medicaid because they did not meet the work-reporting and premium cost-sharing requirements should technically become eligible once again for subsidies under the Affordable Care Act exchanges so long as they meet the requirements for subsidies. However, the complexities of re-enrolling in the exchanges make it unlikely that every qualifying North Carolinian deemed ineligible for Medicaid due to the limitations in HB 655 would successfully re-enroll in a subsidized ACA policy. Some share of these people would be unable to afford health insurance on the exchanges. As a result, hospitals that would have otherwise been reimbursed for providing care covered under Medicaid would once again shoulder the uncompensated care costs for this population.

Why Medicaid expansion is particularly critical for rural hospitals

Medicaid expansion provides a financial lifeline for many struggling rural hospitals. Many of North Carolina’s rural hospitals have either closed in recent years or are at risk of closing in the near future. By dramatically reducing uncompensated care costs for many rural hospitals in North Carolina, Medicaid expansion is likely the single fastest way to put these facilities on more solid economic ground.

Medicaid expansion will expand rural insurance rates and reduce uncompensated care costs

Medicaid expansion would go a long way toward addressing one of the chief financial challenges facing rural hospitals: the cost of providing care to patients without health insurance. When a patient arrives at a hospital’s emergency room, federal law mandates that the hospital assess and stabilize a patient’s condition, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay.11 When a patient does not have insurance, hospitals are often left with no payment for the services they provide. These services provided in the emergency department are particularly costly. One national study estimated that uncompensated care costs hospitals $900 per uninsured patient per year.12 This often happens through formal charity care programs that many nonprofit hospitals provide as a community benefit.

With North Carolina’s uninsured rate among the highest in the nation,13 rural hospitals in our state struggle more than their peers in many other states to cover the cost of uncompensated care. When hospitals have a relatively large share of uninsured patients, as most of North Carolina’s rural hospitals do, more of their services are uncompensated. The cost of providing services, paying employees, and keeping the lights on chip away at a hospital’s profits and revenues, eventually making it difficult to provide services to anyone.

Because rural hospitals have a greater burden of uncompensated care, they also stand to benefit the most from Medicaid expansion, as previously uninsured individuals will gain eligibility for Medicaid coverage, and hospitals will be compensated for more of the services they provide. Medicaid expansion has led to health insurance coverage gains,14 which have reduced hospitals’ uncompensated care costs15 and have led to fewer closures in expansion states compared to non-expansion states.16

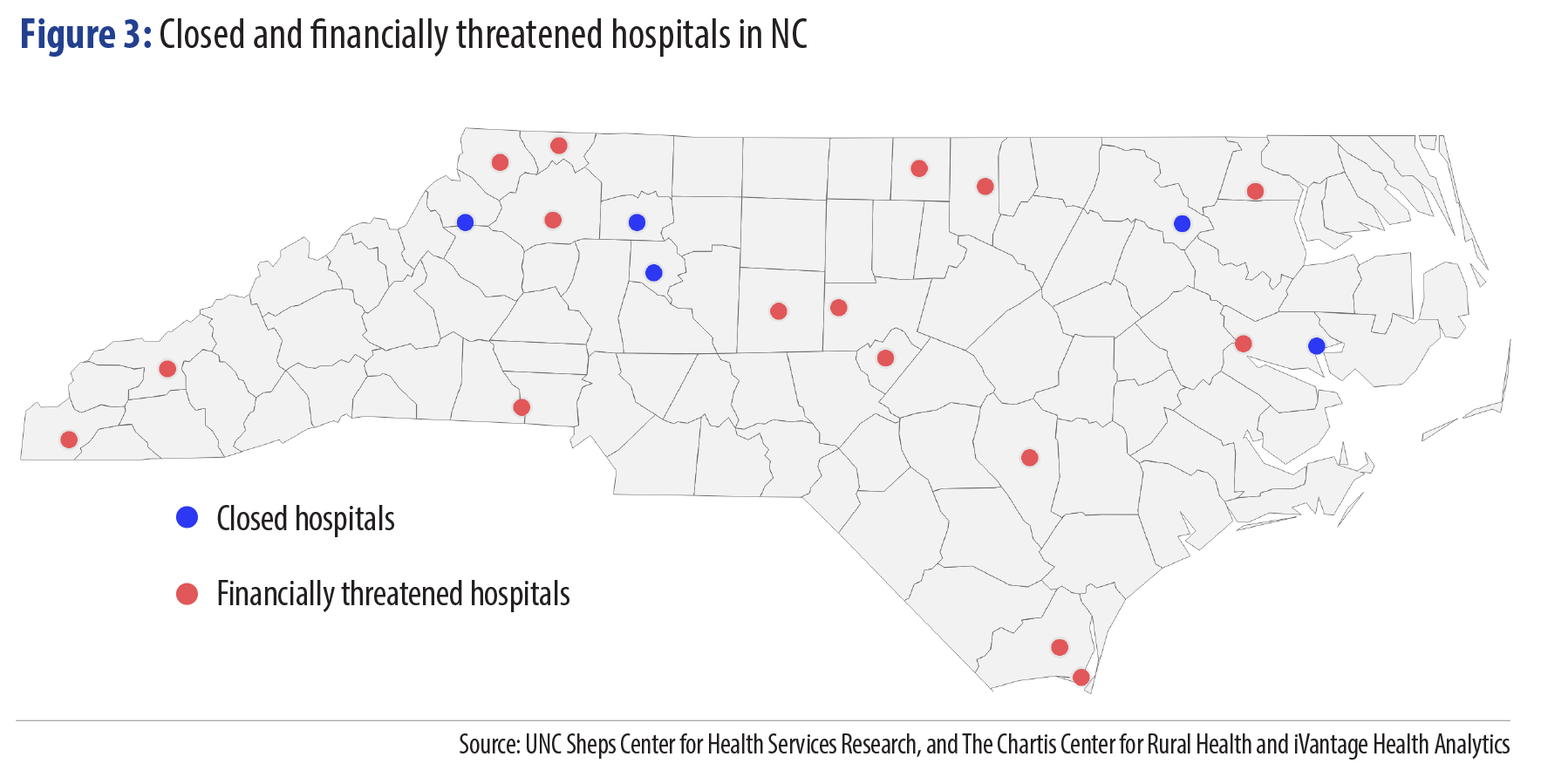

Closed and threatened hospitals concentrated in rural NC

Financial pressures, including uncompensated care costs, have already pushed several North Carolina hospitals into insolvency. Since 2013, five hospitals have closed in rural North Carolina,17 all in areas that could ill afford to lose local sources of health care and jobs. Currently, there are more non-elderly uninsured North Carolinians living in rural areas than in urban areas, a large reason that uncompensated care costs weigh so heavily on rural hospitals.

Of the hospitals that have closed nationally over the past several years, more than a third were designated Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services18 — defined generally as being small and remote hospitals where patients have no other local source of hospital care.19 In North Carolina, four of the five rural hospitals that have closed since 2013 were designated CAHs, leaving the state with only 20 CAHs remaining.20

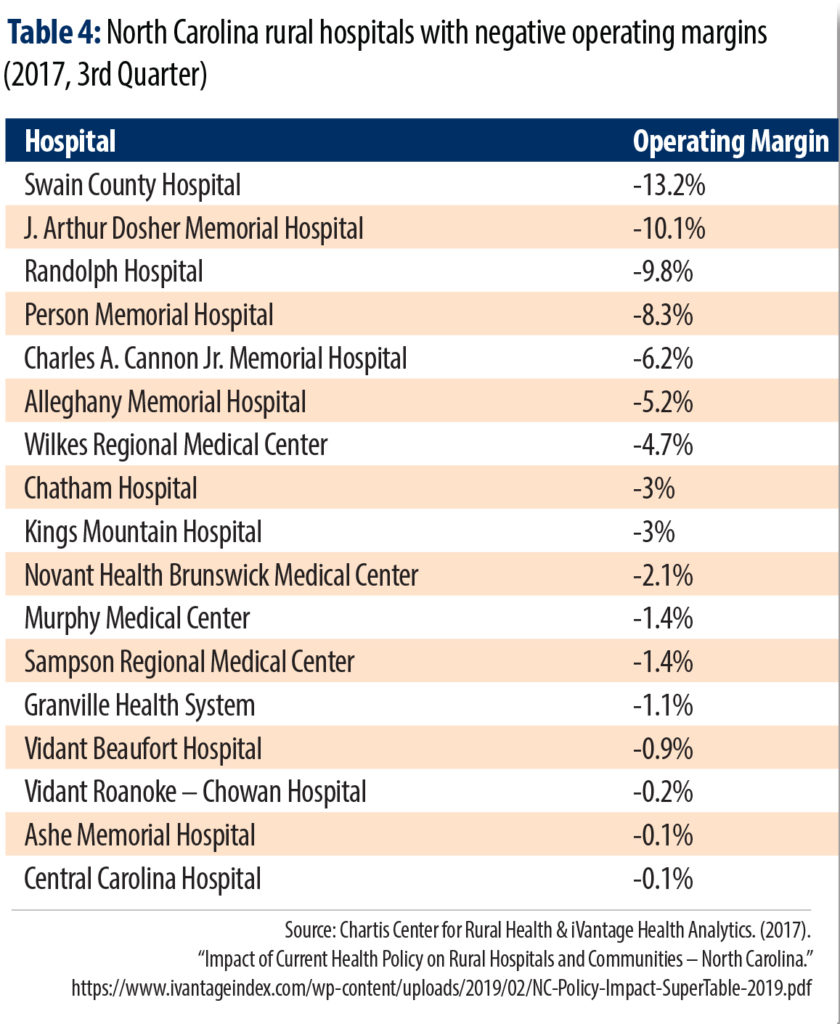

Without Medicaid expansion, more Critical Access Hospitals and other rural hospitals are likely to close. One recent snapshot of rural hospital finances showed that a distressing number of rural hospitals were losing money, and several more were just barely bringing in enough revenues to cover costs. If these rural hospitals are left to face uncompensated care costs that could be alleviated through Medicaid expansion, more of North Carolina’s communities stand to lose their only local hospital.

Hospitals are key to rural economies

Health care is foundational to economic development, but far too many of our rural communities are built on crumbling foundations.21 — Patrick Woodie, NC Rural Center

Hospital closures can have ripple effects that touch every corner of a rural community’s economic life. Hospitals are often essential to the social and economic fabric of rural communities — institutions that shape and organize how rural economies function.22 This section outlines some of the vital economic functions that hospitals serve, which underscore the broader economic benefits of stabilizing these institutions through full Medicaid expansion.

Hospitals as job creation engines

Hospitals provide direct jobs and create business for a range of other industries across the economy. In 2015, hospitals employed over 175,000 people in North Carolina alone.23 Once hospitals’ purchases of goods and services are factored in, and the impact of consumer spending is considered, more than 400,000 jobs and $52 billion in economic activity are supported by hospitals in North Carolina. Similar results were found by another report conducted in 2017.24

Hospitals’ ability to support local employment is particularly vital in rural communities. A study in Oklahoma found that rural hospitals can have the same impact on retail activity as a Wal-Mart, boosting retail activity in communities that have a Critical Access Hospital by 28 percent compared to rural communities without these facilities.25 Hospitals boost employment and generate positive employment spillovers in rural economies,26 and in 44 rural North Carolina counties, a health system (hospital, clinic, etc.) was among the top 5 employers.27

Double-whammy employment impact from lost rural hospital jobs

Unfortunately, the closure of many rural hospitals is removing these key employment drivers from many communities that already struggle to attract and retain jobs. Hospital employment has concentrated in more urban areas in recent years. Even while urban hospital employment continued to grow throughout the Great Recession, rural in-patient hospital employment peaked in 2011, and the decline has been the most dramatic in the most rural communities.

Unfortunately, the closure of many rural hospitals is removing these key employment drivers from many communities that already struggle to attract and retain jobs. Hospital employment has concentrated in more urban areas in recent years. Even while urban hospital employment continued to grow throughout the Great Recession, rural in-patient hospital employment peaked in 2011, and the decline has been the most dramatic in the most rural communities.

The direct job losses created by the loss of rural hospitals do not stop at the emergency room doors. Rural hospital closures often lead physicians and health-care providers outside of the hospital to leave as well, and sometimes even the potential closure of a local hospital will drive local physicians to depart.28 The ripple effects extend even further as the loss of local wages and salaries associated with hospitals then depresses local income that previously supported jobs in the broader economy.

All told, each lost hospital job in a rural community costs another local job, effectively doubling the economic cost of rural hospital closures.29 A study of rural hospitals in the 1990s found that hospital closures significantly increased unemployment and depressed county income.30 Rural communities with another hospital nearby did not suffer long-term economic damage, even more direct evidence that access to hospitals is essential for rural economic success.

Hospitals attract and retain companies

Beyond directly supporting local jobs, hospitals are often key assets in the fight to attract and retain employers. When companies think about where to locate operations, access to quality health facilities plays a significant role.

First, access to hospitals can reduce health-care costs that companies often underwrite through employee health insurance. As health care costs continue to escalate, health care assets like hospitals are likely to become even more enticing to employers deciding where to set up shop.31

“Two of the issues that face rural communities is not just attracting new industries, it’s attracting people to move here and live here who can work in these industries,” says Jay Doneker, mayor of Reidsville in Rockingham County, a rural community. “Medical care is very important for all stages of raising a family and afterwards. And so if we don’t have that hospital, it’s hard to attract employees. It’s also hard to attract people to come back here and spend their retirement years here.”

Hospital access also factors into companies’ ability to attract and retain skilled workers. Particularly in knowledge-intensive industries where employees have many options about where to live and work, companies are increasingly attuned to the importance of locating in places with a high quality of life. As such, rural communities without a local hospital are at an increasing disadvantage in many of the growing industries that rely on skilled employees.

Hospitals keep local workforce healthier and more productive

Perhaps the most profound — and often most underappreciated — economic benefits of hospitals are their contributions to healthier and more productive labor forces. Healthier workers are more energetic and robust, generate higher productivity, earn better wages, and are less likely to be absent from work because of their own illness or an ailing family member.

One long-term study found that for every year of increased life expectancy, a country’s economic output increases by 4 percent,32 and this finding has been corroborated by other findings of a strong relationship between health outcomes and economic performance.33 A more recent analysis by the United States Chamber of Commerce found that ill health is a particular challenge for the United States, where absenteeism, early retirement, and other effects of poor health decreased economic output by over 8 percent.34 The positive impacts of improved health on labor force participation have also been studied specifically in the rural South, providing even more evidence that hospitals are key to rural North Carolina’s long-term economic prospects.35

Conclusion

Medicaid expansion could, in one stroke, profoundly improve the physical and economic health of rural communities. Expansion would ensure lifesaving care for hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians, offer institution-saving support to rural hospitals currently facing financial ruin, and stave off the economic damage that follows hospital closures. It’s past time to make full expansion a reality and end the needless suffering imposed on rural hospitals and the patients they serve.

Appendix: Projected impact of full expansion on North Carolina hospitals

This Appendix reports the projected impacts of full Medicaid expansion on each hospital in North Carolina. Given the complexities in sharing out the overall benefits of expansion, it is likely that the actual impacts on each hospital could differ from the projections presented here.

Based on the forecasted impact of Medicaid expansion in the 3rd year following implementation when full enrollment is forecasted to be achieved, the following table presents an estimate of the impact that hospitals could realize if; 1) each hospital attracts the same market share of the expanded population’s hospital services that they currently enjoy and the differential in payments is the same as the state-wide average, 2) each hospital experiences lost commercial revenues from people converting to Medicaid at the same percentage as the state-wide average, 3) the incremental cost of the new services is the same as each hospital experienced in 2018 and 4) the State allocates the assessment based on payments to the hospitals and not cost. Download a PDF of the Appendix here.

Footnotes

- Wishner, J., Solleveld, P., Rudowitz, R., Paradise, J., & Antonisse, L. (2016). “A look at rural hospital closures and implications for access to care: Three case studies.” http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-a-look-at-rural-hospital-closures-and-implications-for-access-to-care

- Coggin, J. (2018). “Rural Economic Development and Health Care Access.” Presentation to Committee on Access to Healthcare in Rural North Carolina. https://www.ncleg.gov/documentsites/committees/bcci-6715/January%208,%202018/5.%20Coggin,%20Rural%20Healthcare%20and%20Economic%20Success.pdf

- Ku, L., Bruen, B., & E. Brantley. (2019). “The Economic and Employment Benefits of Expanding Medicaid in North Carolina: June 2019 Update.” George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health

- UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/

- Antonisse, L., Garfield, R., Rudowitz, R., & Artiga, S. (2018). “The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: Updated findings from a literature review.” https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/

- Sirota, A., B. Kennedy, & Khachaturyan, S. (2019). “Medicaid work requirement would create new barriers to health in North Carolina.” North Carolina Budget and Tax Center. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/medicaid-work-requirement-would-create-new-barriers-to-health-in-north-carolina/

- Sirota, A., B. Kennedy, & Khachaturyan, S. (2019). “Medicaid work requirement would create new barriers to health in North Carolina.” North Carolina Budget and Tax Center. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/medicaid-work-requirement-would-create-new-barriers-to-health-in-north-carolina/

- Brooks, T. (2013). “Handle with Care: How Premiums are Administered in Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace Matters.” Georgetown Health Policy Institute. http://pophealth.uahs.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/handle-with-care-how-premiums-are-administered.pdf

- Burroughs, M. (2015). “The High Administrative Costs of Common Medicaid Expansion Waiver Elements.” FamiliesUSA. https://familiesusa.org/blog/2015/10/high-administrative-costs-common-medicaid-expansion-waiver-elements

- Congressional Budget Office. (2006). “Additional information on CBO’s estimate for the Medicaid provisions in the Conference Agreement for S. 1932, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005.” https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/109th-congress-2005-2006/costestimate/s1932updat0.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2012). Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/emtala/

- Garthwaite, C., Gross, T., & M. Notowidigdo. (2015). “Hospitals as Insurers of Last Resort.” National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper No. 21290. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21290

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2017). “Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly 0-64.” https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-0-64/

- Broaddus, M. (2017). “Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion Benefits Hospitals, Particularly in Rural America.” https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/affordable-care-acts-medicaid-expansion-benefits-hospitals-particularly-in-rural; Garfield, R., Orgera, K., & Damico, A. (2019). “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid.” https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2018). “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP.” https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP-March-2018.pdf; Dranove, D., Garthwaite, C., & Ody, C. (2016). “Uncompensated Care Decreased At Hospitals In Medicaid Expansion States But Not At Hospitals In Nonexpansion States.” Health Affairs, 35(8): 1471-1479. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344; Dranove, D., Garthwaite, C., & Ody, C. (2017). “The Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on Hospitals’ Uncompensated Care Burden and the Potential Effects of Repeal.” https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/may/impact-acas-medicaid-expansion-hospitals-uncompensated-care?redirect_source=/publications/issue-briefs/2017/may/aca-medicaid-expansion-hospital-uncompensated-care

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2018). “Rural Hospital Closures: Number and Characteristics of Affected Hospitals and Contributing Factors.” https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694125.pdf; Lindrooth, R. C., Perraillon, M. C., Hardy, R. Y., & Tung, G. J. (2018). “Understanding The Relationship Between Medicaid Expansions And Hospital Closures.” https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976; Blavin, F. (2016). “Association Between the 2014 Medicaid Expansion and US Hospital Finances.” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2565750; Holmes, G. M., Kaufman, B. G., & Pink, G. H. (2017). “Financial Distress and Closure of Rural Hospitals.” https://www.ruralhealthresearch.org/assets/540-1584/9212017-financial-distress-closures-of-rural-hospitals-ppt.pdf

- UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research. (2019). “113 hospital closures: 2010 to present.” https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/

- UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research. (2019). “113 hospital closures: 2010 to present.” https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2018). “Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs).” https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/critical-access-hospitals

- NC Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Rural Health. (2018). “North Carolina Rural Hospital Program.” https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/2018%20NC%20DHHS%20ORH%20Hospital%20Program%20One%20Pager_0.pdf

- Woodie, P. (2018). “What’s Economic Development Got to Do with It? The Economic Impact of Healthy Rural Communities.”North Carolina Medical Journal. Vol. 79, No. 6. http://www.ncmedicaljournal.com/content/79/6/382

- NC Budget and Tax Center. (2018). Crucial Connections: How Public Works Can Boost North Carolina’s Workforce and Connect Rural N.C. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/state-of-working-north-carolina-2018-crucial-connections/

- American Hospital Association. (2017). “Hospitals are Economic Anchors in their Communities.” https://www.aha.org/system/files/content/17/17econcontribution.pdf

- Oliver, Z., Lim, B., & J. Woolacott. (2017). “The Economic Impact of Hospitals and Health Systems in North Carolina.” RTI International. https://www.ncha.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/2017-NC-Hospitals-Economic-Impact-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Brooks, L., & B. Whitacre. (2010). “Critical Access Hospitals and Retail Activity: An Empirical Analysis in Oklahoma.” Journal of Rural Health. Vol. 27, Issue 1.

- Mandich, A. & J. Dorfman. (2017). “The Wage and Job Impacts of Hospitals on Local Labor Markets.” Economic Development Quarterly. Vol. 31, Issue 2.

- Coggin., J. (2018). “Rural Economic Development and Health Care Access.” Presentation to Committee on Access to Healthcare in Rural North Carolina.

- The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. (2016). “A Look at Rural Hospital Closures and Implications for Access to Care: Three Case Studies.” http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-a-look-at-rural-hospital-closures-and-implications-for-access-to-care

- Miller, C., Pender, J., & T. Hertz. (2017). “Employment Spillover Effects of Rural Healthcare Facilities.” United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/86254/err-241.pdf

- Holmes, G. EA. (2006). “The Effect of Rural Hospital Closures on Community Economic Health.” Health Services Research. Vol. 41, Issue 2.

- Crawford, M. (2012). “Is Healthcare Part of the Facility Location Decision?” Area Development.

- Bloom, D., Canning, D., & J. Sevilla. (2001). “The Effect of Health on Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence.” National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 8587. https://www.nber.org/papers/w8587.pdf

- Bloom, D., Canning, D., & J. Sevilla. (2004). “The Effect of Health on Economic Growth: A Production Function Approach.” World Development. Vol. 32, No. 1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X03001943; Amiri, A., & U. Gerdtham. (2013). “Impact of Maternal and Child Health on Economic Growth: New Evidence Based on Granger Causality and DEA Analysis.” Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health https://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/part_publications/201303_Econ_benefits_econometric_study.pdf; Chirikos, T., & N. Gilbert. (1985). “Further Evidence on the Economic Effects of Poor Health.” Review of Economics and Statistics. Vol: 67, No: 1.

- Rasmussen, B., Sweeny, K., & P. Sheehan. (2016). “Health and the Economy: The Impact of Wellness on Workforce Productivity in Global Markets.” US Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/documents/files/global_initiative_on_health_and_the_economy_-_report.pdf

- Scott, L., Smith, L., & B. Rungeling. (1977). “Labor Force Participation in Southern Rural Labor Markets.” American Journal of Agriculture Economics. Vol: 59, No: 2. https://ideas.repec.org/a/oup/ajagec/v59y1977i2p266-274.html

Justice Circle

Justice Circle