Controversial Forest-Thinning Project Requests Public Comment

Los Padres Proposes 235,000-Acre Tree-Health and Fuel-Break Project

This Monday and Wednesday, August 8 and 10, a tree- and brush-removal project for Los Padres National Forest will be up for discussion in two virtual meetings. The work would remove trees and brush overcrowded from a century of fire suppression. It’s also intended to protect the “wildland-urban interface,” or WUI, as Los Padres borders thousands of homes across Carpinteria, Montecito, Santa Barbara, and Goleta. However, another school of thought argues the money would be better spent on measures such as fire-resistant roofs and closing up vents — methods known as home-hardening — to directly protect residences and buildings in the WUI.

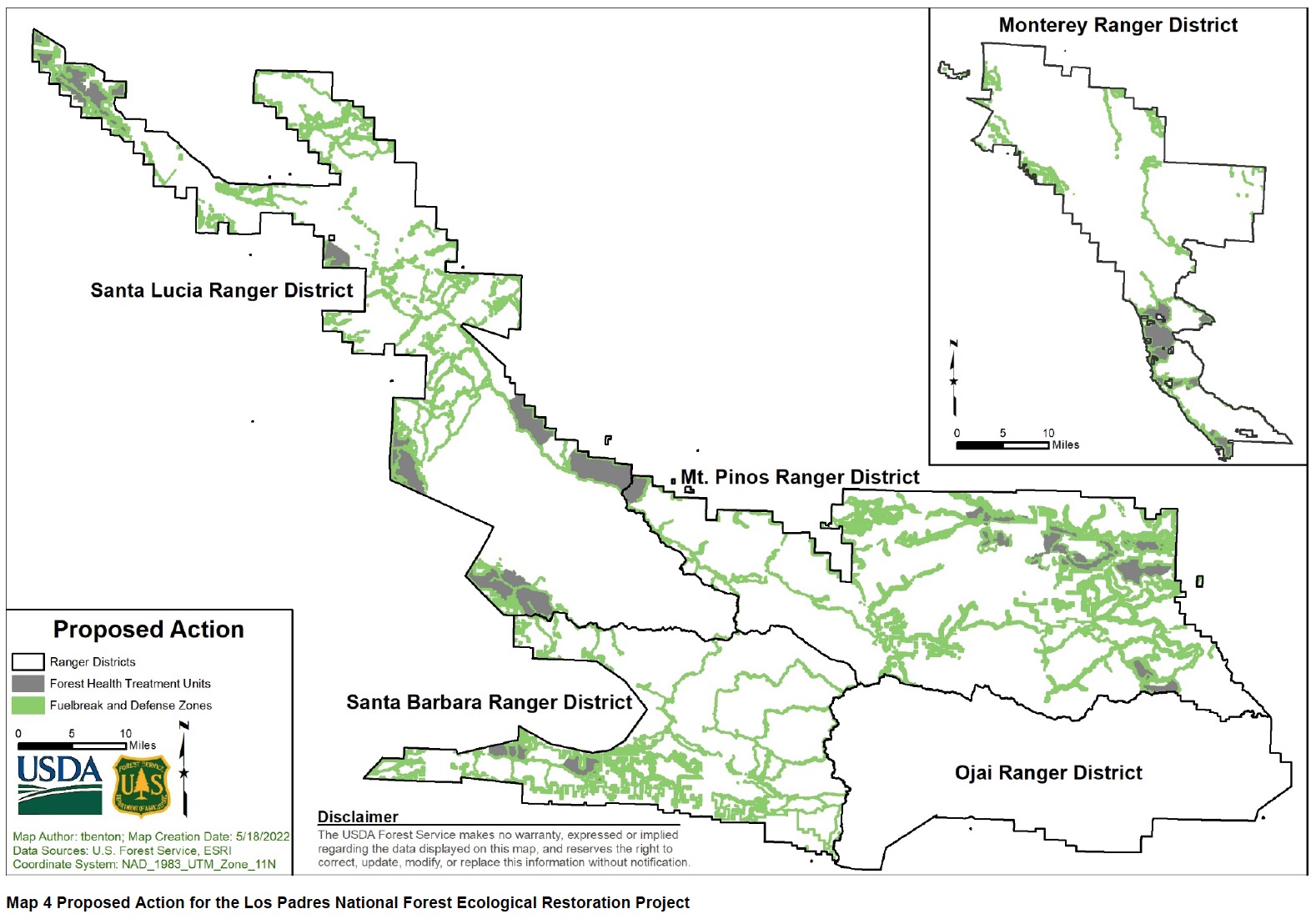

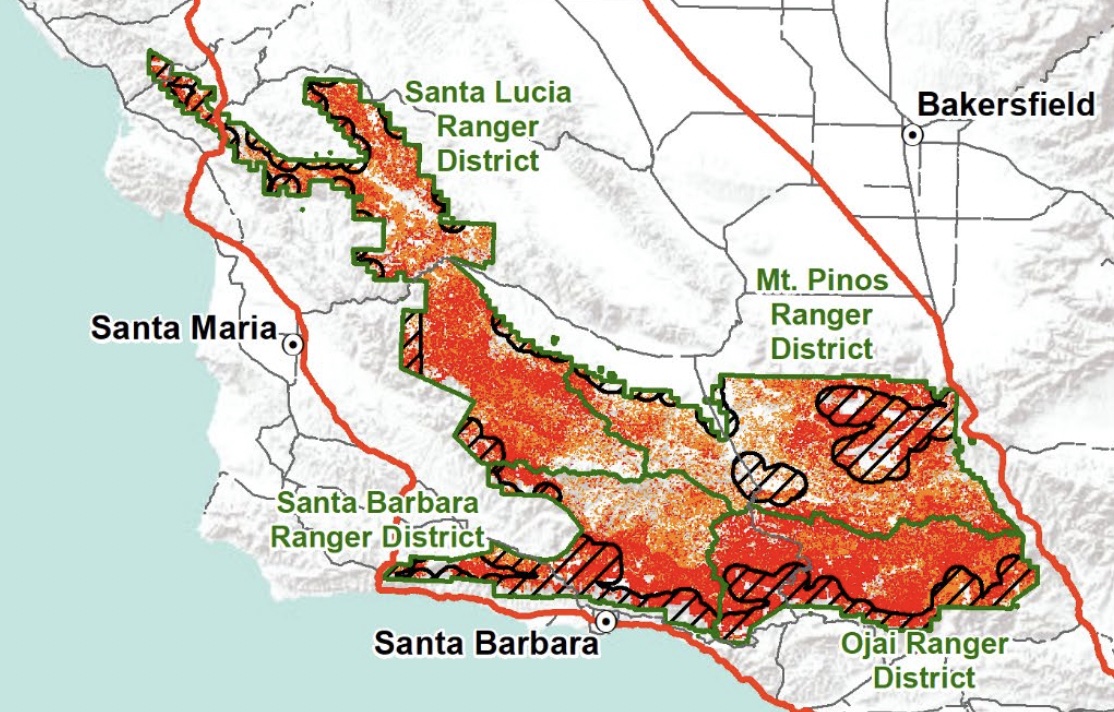

The project encompasses 235,495 acres north to Monterey County. Los Padres as a whole is 2 million acres, stretching 200 miles from Los Angeles to Monterey counties. Four of its five ranger districts are part of this project: Monterey, Santa Lucia, Santa Barbara, and Mt. Pinos.

The project has two parts: one for forest health and one for fuels reduction, summarized in a 17-page “Purpose & Need and Proposed Action” report with maps. Among other techniques, the Forest Service states it plans to use controlled burns to “restore fire-adapted ecosystems,” particularly in chaparral zones that include plants that need fire to seed and sprout. Cutting by hand or machines, chipping, masticating, and grazing are other removal methods.

The report describes how fires in Los Padres have been suppressed over the past 90 years, leading to frequent chaparral burns and less frequent burns among conifers — pines and fir trees — and hardwoods like oaks. As well, the fire frequency outlook for California is one of increased fire activity. The CO2 that causes climate change also increases plant growth. It will cause the weather to grow wetter at times, increasing plant growth, and drier with more thunder activity at others. The result is a recipe for “frequent, intense wildfire in western forests,” according to the EPA.

Opposing Viewpoints

Battle lines were drawn soon after the Forest Service sent its request for comments at the end of July. The Coalition of Labor and Agriculture (COLAB) regards the project as a “major opportunity to end never-ending forest fires” by thinning trees that are 10 times the optimal level for a healthy forest ecosystem. “[W]hen there are too many trees and too much underbrush in a forest, the trees find it very difficult to compete for sunshine, nutrients, and water. The trees then become weakened and susceptible to pests and diseases. They end up dying and becoming fuel for ravaging forest fires,” COLAB director Andy Caldwell wrote in an email.

That describes the “forest health” portion of the project, which is slated for about 48,000 acres. The “fuels reduction” portion totals 186,000 acres and includes fuel breaks, shaded fuel breaks, and reductions in surface and ladder fuels.

In opposition to the project, Los Padres ForestWatch produced a press release that objected to a “timber harvest” of trees up to 24 inches in diameter, as well as the damage inflicted by heavy equipment rolling through the forest and the aftereffect of an invasion by non-native plants. The fuel breaks of 1,500-2,500 feet in width would be in areas relatively remote from housing and of little effectiveness in the face of embers that fly up to a mile in heavy winds. ForestWatch stated that $1.6 million in funding for the project’s environmental review comes from PG&E; Ojai is outside PG&E’s range, which is why the Ojai Ranger District is not in this project.

What would be a better use of the funding, ForestWatch argued, was to do what scientists and conservation organizations have long suggested: create defensible space next to homes, retrofit them with fire-resistant materials, and reduce development in the wildland-urban interface.

ForestWatch and other environmental organizations have challenged the Forest Service several times in similar projects, attempting to set boundaries on proposals in the Ojai backcountry in the past several years. Of those challenges, the Cuddy Valley and Tecuya Ridge projects were appealed; the Forest Service prevailed in Cuddy Valley, but the judges want more justification for the felling of 21-inch trees at Tecuya Ridge. Another called Reyes Peak is in litigation, a similar fuel-break proposal for Pine Mountain that got strong public pushback. Those projects were measured in a couple thousand acres or less.

The Question of Climate Change

What was not part of the debate was the carbon that would be released into the atmosphere from controlled burns. Steve Windhager, a fire ecologist and director of the Santa Barbara Botanic Gardens, explained that a controlled burn has a lower intensity and avoids damaging mature trees; the bulk of the carbon would stay in those species, and the burst of growth that follows sequesters the carbon again: “Where fuel reduction is needed to save communities or to reduce fuel build up from past fire suppression, then prescribed fire is typically the least CO2-emitting method to reduce that fuel load.”

Windhager commented there were a lot of “gray” areas to the debate. He said the data was strong in showing “prescribed fire use reduces the number of structures damaged by wildfires occurring later. Also, prescribed fire does not have as many unintended consequences associated with invasive species spread or negative impacts on ecological health.”

But then there are the burns that get away from the best managed controls — a pile burn in New Mexico this past January survived three snowfalls to puff to life during April winds. It joined up with a prescribed burn, and the Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire grew to a 341,000-acre conflagration that burned hundreds of structures. Windhager noted that the high-profile burns that get out of control are far from common. “But the stakes are very high — but so is doing nothing.”

Nonetheless, the fire suppression of the past created dense stands of vegetation that could arguably be removed. “All that said,” Windhager continued, “the single greatest thing that can be done to reduce home loss in the WUI as a result of wildfire is increased investment in home hardening. Most homes burn from the inside out when embers are carried by winds into their attics or find other intrusions inside the buildings. Home hardening also has no adverse effects with regard to unintended ecological impacts to our wildlands. It makes sense that this should be our first choice for how to make our communities safer.”

In a letter sent to President Biden last November, more than 200 scientists made a climate argument in favor of retaining trees. Ahead of the president’s reconciliation bill, which included forest management funding, they noted that logging in U.S. forests adds 723 million tons of CO2 into the air. Also, “commercial logging conducted under the guise of ‘thinning’ and ‘fuel reduction’ typically removes mature, fire-resistant trees that are needed for forest resilience,” the letter stated, adding that commercial logging and removing trees “can alter a forest’s microclimate, and can often increase fire intensity.” Rather than logging, it was better to store carbon in mature and older forests, and to allow regenerating forests to accumulate carbon, they averred.

How to Send Comments

To learn more about the Ecological Restoration Project for Los Padres National Forest, visit fs.usda.gov/project/?project=62369.

To participate in the two virtual meetings for Los Padres National Forest’s project:

- Monday, August 8, 2022, 6:00 – 7:30 pm, Teams Live virtual meeting, https://tinyurl.com/LPNF-ERP-Mgtn-1

- Wednesday, August 10, 2022, 6:00 – 7:30 pm, Teams Live virtual meeting, https://tinyurl.com/LPNF-ERP-Mgtn-2

Comments must be submitted by August 28, 2022, to: https://cara.fs2c.usda.gov/Public//CommentInput?Project=62369. Written comments go to: Los Padres National Forest Supervisor’s Office, Attention: Kyle Kinports, 1980 Old Mission Drive, Solvang, CA 93463. Write “LPNF Ecological Restoration Project” on the envelope and in the comment letter.

Correction: This story was corrected to state an appeal sent the Tecuya Ridge project back to the lower federal court to require the Forest Service to explain why 21-inch diameter trees were “small” for an 1,100-acre roadless area. It remains in litigation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.