Out of Oakland, a number of harrowing, grainy videos have caught widespread attention in recent weeks, showing elderly people in Chinatown being attacked or robbed while working or going about their daily lives.

In one video that has been viewed millions of times, a 91-year-old man strolling along 8th and Harrison is violently shoved, headfirst, into the pavement. (Initial media reports incorrectly identified the man as Asian; he is Latino.) Chinatown merchants say robberies have increased dramatically in recent weeks.

About this report

This is part one of a series; read part two.

This article has been translated to Chinese. Read the traditional version (繁體中文版) or simplified version (简体中文版).

This report was produced in collaboration with Oakland Voices, a program led by the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education to train Oakland residents to tell the stories of their neighborhoods.

Alvina Wong is the Campaign and Organizing Director at the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, a nonprofit organization that organizes working-class Asian immigrant and refugee families to push for a clean and healthy environment. APEN has been headquartered in Oakland Chinatown since 2002.

Wong stressed that pandemic-fueled anti-Asian hate is not necessarily linked to the current rise in crimes in Chinatown, noting that robberies in Chinatown take place year-round, particularly around Lunar New Year. “These crimes and violent situations that happen in Chinatown have been happening for a while,” she said.

But Wong says it’s impossible to divorce the pressure and fear residents have been enduring for over a year from the massive outcry over what’s happening now. Chinatown, already shrinking before the pandemic, has been particularly hard-hit by shelter-in-place orders and the economic collapse. As many as a third of all Chinatown businesses are closed permanently or temporarily due to COVID, with notable restaurants closing or signaling they might have to. “How much can we take before we break? It feels like a breaking point for many people,” said Wong.

The recent physical assaults caught on camera have drawn international attention and response. National media outlets from Fox News to The Guardian have picked up various threads of the story. Actors Daniel Wu, who attended a private school in Oakland, and Daniel Dae Kim donated $25,000 toward finding one suspect. President Joe Biden’s press secretary was even asked this week about the recent footage of attacks on elderly Asian Americans and whether the president has “seen the videos.”

During a widely covered Feb. 3 press conference held at the Pacific Renaissance Plaza, in the heart of Chinatown, Mayor Libby Schaaf criticized City Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas’s unsuccessful budget proposal last summer to cut police funds that, according to Schaaf, protect Chinatown residents and businesses. Bas and councilwoman Carroll Fife pushed back, pointing out that recent cuts to Chinatown police presence were made by the mayor’s administration, and accusing Schaaf of sowing division between Black and Asian communities.

Suspects and defendants in the couple of Oakland Chinatown cases that have garnered widespread attention in recent weeks were Black. Calls for increased police presence in Chinatown have come with serious concerns about Black Oaklanders shopping or otherwise spending time in the commercial district being profiled, criminalized, and harmed.

Civilian-led foot “strolls” through Chinatown have been organized by groups like the Oakland Chinatown Coalition, Asians with Attitudes, Compassion in Oakland, and the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce. People from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds have participated in these events. Several GoFundMe campaigns have sprung up, pledging to fund victims of assaults and Asian-American advocacy organizations and raising tens of thousands of dollars.

Across social media, many have claimed that the shocking assaults and the perceived uptick in robberies represent hate crimes, lingering effects of well-documented rise in anti-Asian sentiment and attacks that swelled at the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

Is there evidence that what Chinatown has experienced in recent weeks is racially motivated? Are we really seeing a unique uptick in crime there, unlike years past, and divorced from what’s happening elsewhere and to other communities in Oakland? Why have recent crimes in Chinatown attracted searing attention locally and even internationally, while gun violence has spiked dramatically in parts of East Oakland for months with less sustained concern and civic response? What do Chinatown residents want to see happen in terms of solutions, and whose voices aren’t being heard?

In the intense swirl of national media coverage and celebrity attention, political finger-pointing, viral footage, and impassioned pleas for greater solidarity between two communities that have historically been pitted against each other, important questions have not been adequately answered, or even explored. In this two-part report, we attempt to do so.

We spoke to victims, activists, elected officials, community members, and community leaders—especially those connected with the Oakland Chinatown Coalition, a network formed over 10 years ago of neighborhood nonprofits, businesses, churches, residents, and more—about the recent high profile incidents of crime in Oakland Chinatown, what’s been missing from the conversations they’ve been seeing, and where to go from here.

Were recent assaults and robberies in Chinatown racially motivated?

Over the course of one day, Jan. 31, Yahya Muslim, a 28-year old unhoused man, allegedly attacked three people in Chinatown. Surveillance video captured Muslim shoving the 91-year-old senior at 8th and Harrison. After the footage went viral and international, actors Kim and Wu teamed up to offer a $25,000 reward for what they have repeatedly described as an example of rising hate crimes targeting Asian-Americans.

The Oaklandside looked at Muslim’s court record and found that he has been arrested in several cities in Alameda County over the past nine years for various types of crimes, including vandalism, shoplifting, and a number of assaults. In August 2020, he repeatedly punched an Asian man in an unprovoked incident on 10th Street near Washington. But there is no clear indication that victims in other attacks by Muslim, which police, witnesses, and victims described as “random” and “unprovoked,” were all Asian or members of any specific community, or that he’s ever attacked anyone because of their race or identity.

In November 2019, Muslim threw a chair at an Uptown bakery employee, cutting the man’s face open. In March 2017, Muslim punched a Safeway employee in Pleasanton. In 2016, he randomly punched the back of a stranger’s head with a closed fist while walking down a street in Livermore. There were two other random attacks on strangers in 2015.

The Oaklandside reviewed police reports, court transcripts, and other publicly available information about these cases. The police reports did not list the victims’ race or ethnicity, but our review of Muslim’s entire court files, including but not limited to his victims’ names, did not indicate that Muslim was systematically targeting any racial or ethnic group. This week, we asked the district attorney’s office whether there is any evidence in Muslim’s court files that he was motivated to attack past victims because of their race or ethnicity. The DA’s office told us they’re reviewing his case.

The Alameda County Public Defender’s office has represented Muslim in the past and is also in the early stages of reviewing the most recent incidents. But Public Defender Brendon Woods said “so far there is absolutely no evidence of xenophobia against Asian Americans,” and that, “connecting this case to a rise in racist violence against Asian Americans is not appropriate and it should not influence the district attorney and the courts as Mr. Muslim’s case makes its way through the system. This case should not be used to pit minority against minority.”

In total, Muslim has been charged at least 10 times with assault, and has never been charged with a hate crime. Six years ago, an Alameda County superior court judge noted in a court hearing that Muslim has “significant mental health issues.” In 2020, he was enrolled for addiction issues at a recovery center in East Oakland.

According to a police records, a witness contacted OPD and identified Muslim as the assailant in the Jan. 31 assaults. Muslim was already in custody: he had been arrested on Feb. 1 after he assaulted several other people on Harrison Street in Chinatown and was placed on a psychiatric hold at John George Hospital in San Leandro. He was taken from John George to Santa Rita Jail on Feb. 5.

Alongside Muslim’s physical attacks, Chinatown has experienced a recent uptick in robberies and petty theft—which we’ll explore in part two of this report. Surveillance footage of some incidents has also been widely viewed and decried as more evidence of anti-Asian sentiment. But some people we spoke to who are deeply involved in Chinatown say they don’t see it that way.

Sakhone Lasaphangthong works at Family Bridges in Chinatown as director of housing services, working with unhoused residents by providing meals and helping people apply for IDs and access healthcare and other resources. He’s also a former Chinatown Clean Ambassador, a program started in 2017 by the Asian Prisoner Support Committee, Asian Health Services, and the Chinatown Improvement Initiative (which later became GoodGoodEatz), and partly funded by East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation and the Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce. The ambassadors removed graffiti and worked with several merchants to improve the district, while also keeping an eye on the neighborhood.

That program was discontinued during the pandemic, though Lasaphangthong continued to volunteer his time. He was re-hired six months ago part-time in a similar role by the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, essentially providing the same support in the community.

Lasaphangthong doesn’t see the uptick in robberies as tied to race. “I don’t see people just targeting Asians. They’re targeting vulnerable people,” he said. “I don’t see it as Blacks against Asians. I see it as crimes of opportunity.”

Lasaphangthong said he has a unique perspective on the situation due to his own background. “I was a criminal. I was imprisoned for 20 years,” he said. “These are the things we do—if we see someone carrying a high name-brand purse, it doesn’t matter what color the skin is. We don’t know what is inside the purse, but just because we want that purse. That’s the crime that I see around here—not because of race.”

Finnie Phung, co-owner of Green Fish Seafood on 8th Street, said that elderly people she sees and interacts with in Chinatown are particularly vulnerable to robberies. The prevalence of elders out and about in Chinatown lends to the perception—and, in some cases, the reality—that the neighborhood is an easier target. “A lot of bystanders are seniors, so they can’t help. Not everyone is young and can run.”

According to U.S. census data, the commercial district of Chinatown is home to about 3,000 Oaklanders who are mostly Asian and significantly older than the rest of Oakland. Forty three percent of the population is aged 60 and older; half of all residents are over 55 years old. Over 30% of all residents live below the poverty line. Most people speak a language other than English at home.

Whether or not racial or ethnic hatred is ramping up crime in Chinatown right now, fears of xenophobia—prejudice, fear, and hatred of people from different cultures—are real and serious. Merchants, organizers, and residents referenced the lasting psychological impacts of the rise in anti-Chinese sentiment and physical and verbal attacks triggered by the start of the pandemic, fueled by the Trump administration’s dangerous rhetoric blaming China and Chinese people for the coronavirus.

Like most other major police departments in California, OPD tracks hate crimes and reports statistics each year to the state Attorney General. The AG’s office makes this data available to the public, and while numbers aren’t posted yet for 2020 and 2021, it does provide a view into which communities in Oakland have reported hate crimes in the past. It shows that LGBTQ people and Black people reported being victimized because of their identities more than any other groups. Asian people reported fewer hate crimes to the police than Black, white, and Latino victims.

The data could be skewed by some groups feeling more comfortable reporting incidents to the police than others, language barriers that prevent accurate reporting, and other problems. They probably underestimate the total number of hate crimes occurring across communities in Oakland. And until data for last year is released, we won’t know the impact of the pandemic, and associated hate and fear, on these statistics.

It’s also important to note that anti-Asian sentiments in America have existed long before COVID-19. In California and the rest of the western U.S., Chinese immigrants were massacred, burned, and killed in the 19th- and early-20th centuries, violence rooted in white supremacy. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese laborers from immigration to the United States essentially until 1965, when the Immigration and Naturalization Act was passed. Chinese people already living in the U.S. also could not gain citizenship. The act is remembered as the first piece of major federal legislation barring a specific community from immigrating to the U.S.

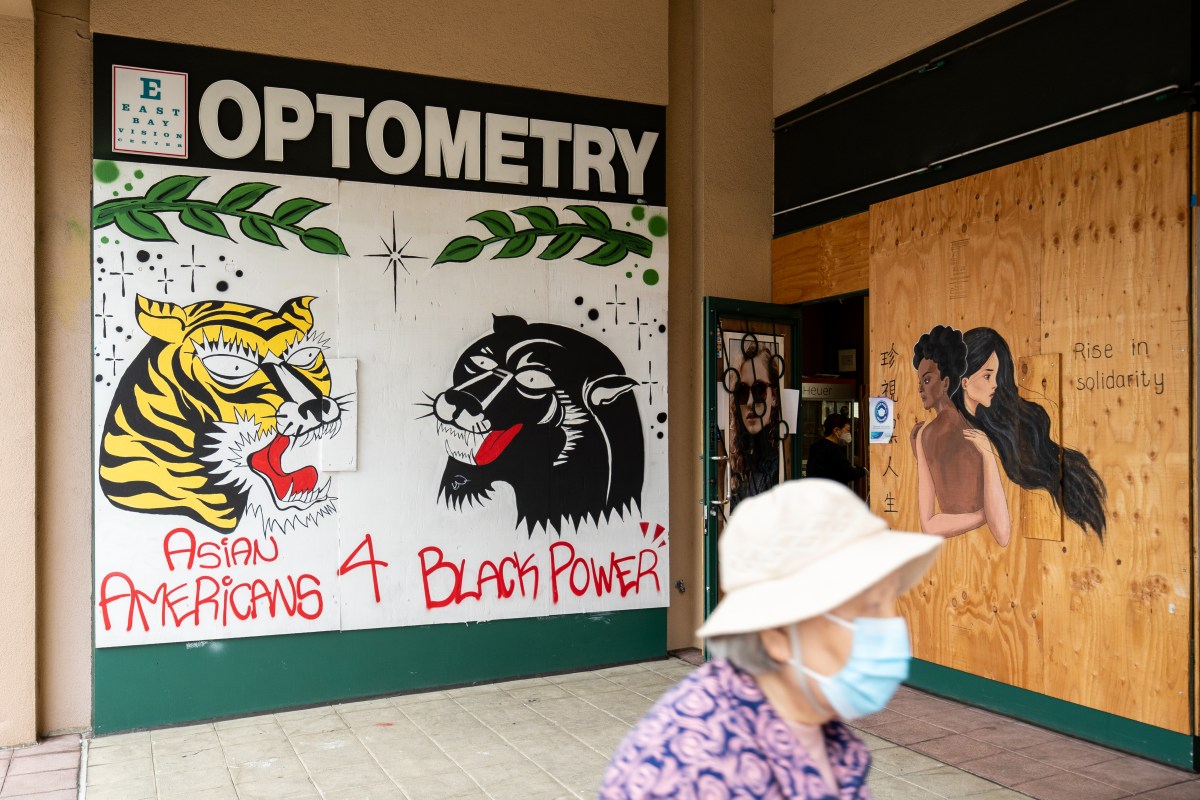

Kev Choice, an Oakland-based musician, educator, and activist, grew up in East Oakland and near Lake Merritt, and says many of his friends and classmates were Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chinese, and many other ethnicities. This past Sunday, Kev Choice, who is Black, went to Chinatown to encourage solidarity between the Asian and Black communities in Oakland. “It was important to set an example and reach out,” he said. “We need to make sure we get rid of tension between Black and Asian communities in this difficult time. We show up for people in crisis and when people are feeling pain. That goes back to Black Panthers and Occupy Oakland, which have always been multigenerational and multiracial.”

He also tied the recent attacks in Chinatown to ongoing crises of poverty in Oakland, from homelessness to lack of mental health care, and despite the suffering and struggle, that this is an opportunity to create change. “Every time there’s a challenge, there’s an opportunity to be more intentional about creating the world and unity we want to see,” he said.

Calls for more police presence and civilian patrols in Chinatown, with mixed welcome

For some people who have been working on the ground in Chinatown for years or decades, the sudden influx of attention, volunteer foot patrols, GoFundMe campaigns raising tens of thousands of dollars in a matter of days, and more has been overwhelming. Some said it felt as though outsiders were coming in without knowing what the community wanted or really needed, and without consulting people with neighborhood knowledge. “People’s care and concern for our elders is beautiful,” Wong of APEN said. “However the categorization that nothing has been done and no one is caring for our communities feels misguided. We’re all working together, trying to coordinate different efforts and it’s great to see how many people are wanting to follow our lead in this moment.”

Wong believes all of the outpouring has been well-intentioned and sparked by a genuine desire to help. But she cautioned that healing in Chinatown will take time and sustained attention, long after the current spotlight of media and civic interest fades, especially when it comes to elders who’ve been victims of assault. “They have long-term health impacts that take a long time to recover from. We check on them regularly, not just this one time because of this media hit.”

Carl Chan of the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce was the organizer of last week’s widely publicized press conference in which the mayor criticized the city council president’s proposal made last summer, in the midst of massive nationwide protests over police brutality, to divert funds away from OPD and toward other kinds of responses to crime, mental illness, and poverty. (That proposal, which was not successful, did not call for reduced police presence in Chinatown, but Schaaf believes that it was such a large cut it would have necessarily led to a reduction in police patrols across the entire city.)

In December, as part of a larger package of cuts, Oakland’s city administrator, Ed Reiskin, who is managed by Mayor Libby Schaaf, did cut three beat patrol officers from Chinatown, including an Asian-American liaison officer who is bilingual in Cantonese and English.

Chan said that having an officer assigned to Chinatown who spoke Cantonese helped ensure that more residents felt comfortable reporting crimes and helped them report what happened accurately. In his request to the mayor at a press conference, Chan asked the mayor to bring back the Asian-American liaison officer if possible. The mayor has stated that there are no plans to bring removed officers back to Chinatown at this point.

Chan also asked for a number of other ways to potentially increase safety, including more parking spots located closer to shops and more surveillance cameras on the street. He added that resources should also go into crime prevention. “We are spending so much resources solving crime but if we can prevent crimes from happening, then we don’t have to spend all these resources.”

Some we spoke to noted that the Oakland Police Department’s headquarters are located just outside the border of Chinatown, and that while many of the shocking incidents that have garnered widespread attention in recent weeks took place two or three blocks away from OPD’s main building, that presence didn’t deter or interrupt these crimes.

Some pointed out that Chinatown isn’t only home to Asian residents, and that Asian residents live elsewhere in Oakland, too. “There are Latinx people that live in and around Chinatown. There are Asian and Pacific Islander folks who live in deep East Oakland,” said Oakland resident and activist Bo Chung, whose family immigrated to Chinatown in the 80s. “Enough with these narratives that are not serving us that continue to divide us. [We need to] get away from demonizing, or finding someone to blame or punish. We need transformative justice to make changes to a system that is failing all of us.”

Meanwhile, many wonder why ongoing crises of crime and violence in other parts of Oakland receive less attention from the media, politicians, and celebrities. Like other cities, Oakland has seen a disturbing rise in shootings and homicides since March 2020. Last year, the city experienced 102 murders, a 26% increase over the three-year average. Shootings spiked last year, rising from 284 in 2019 to 485. And in the first month of this year, 15 Oaklanders were killed compared to 1 person over the same timeframe last year. The majority of Oakland’s homicide victims are Black and Latino men, and most killings happen in East and West Oakland neighborhoods where Black and Latino people are the majority of the population.

“In East Oakland, where there are shootings that threaten Black lives literally every day, we can stand in solidarity and support that crisis, as we also stand in solidarity in what’s happening in Oakland Chinatown to Asian elders,” said City Council president Nikki Fortunato Bas, whose district includes Chinatown, in an interview.

More than anything, APEN’s Wong said that she’d like to see the city and all Oaklanders find ways to celebrate and support the best of what Chinatown has to offer. “Walking through Chinatown, especially when we’re not in a pandemic, is a joyful, sweet experience of pink pastry boxes shared between grandparents and grandchildren they’re picking up from school, small groups of elders laughing together as they stroll to the park or get dim sum,” she said. “I want to see more intergenerational connections and multiracial conversations that are happening in multiple languages. There’s a lot of fear, pain, and hurt in the community and it would be great to see more trust being built and elevated overtime.”

“I’d like to see shops feeling resourced enough and comfortable enough to stay open later, bring in some vibrancy in the evening times with more lighting, and more activity on the street,” said Wong. “That also means people have to keep coming to Chinatown and feeling like it’s okay to be in the neighborhood after dark.”

About this report

This is part one of a series; read part two.

This article has been translated to Chinese. Read the traditional version (繁體中文版) or simplified version (简体中文版).

This report was produced in collaboration with Oakland Voices, a program led by the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education to train Oakland residents to tell the stories of their neighborhoods.

This story was updated April 9, 2021 to clarify that the 91-year-old man attacked in Oakland Chinatown, in an incident that was recorded in a video that later went viral, was not Asian. The man was Latino.