Advertisement

Chinatown’s 9-man tournament takes its Labor Day showdown to Providence

Resume

More than 2,500 athletes from the U.S. and Canada will compete at the Rhode Island Convention Center this weekend in an annual “9-man” volleyball tournament, a Labor Day tradition.

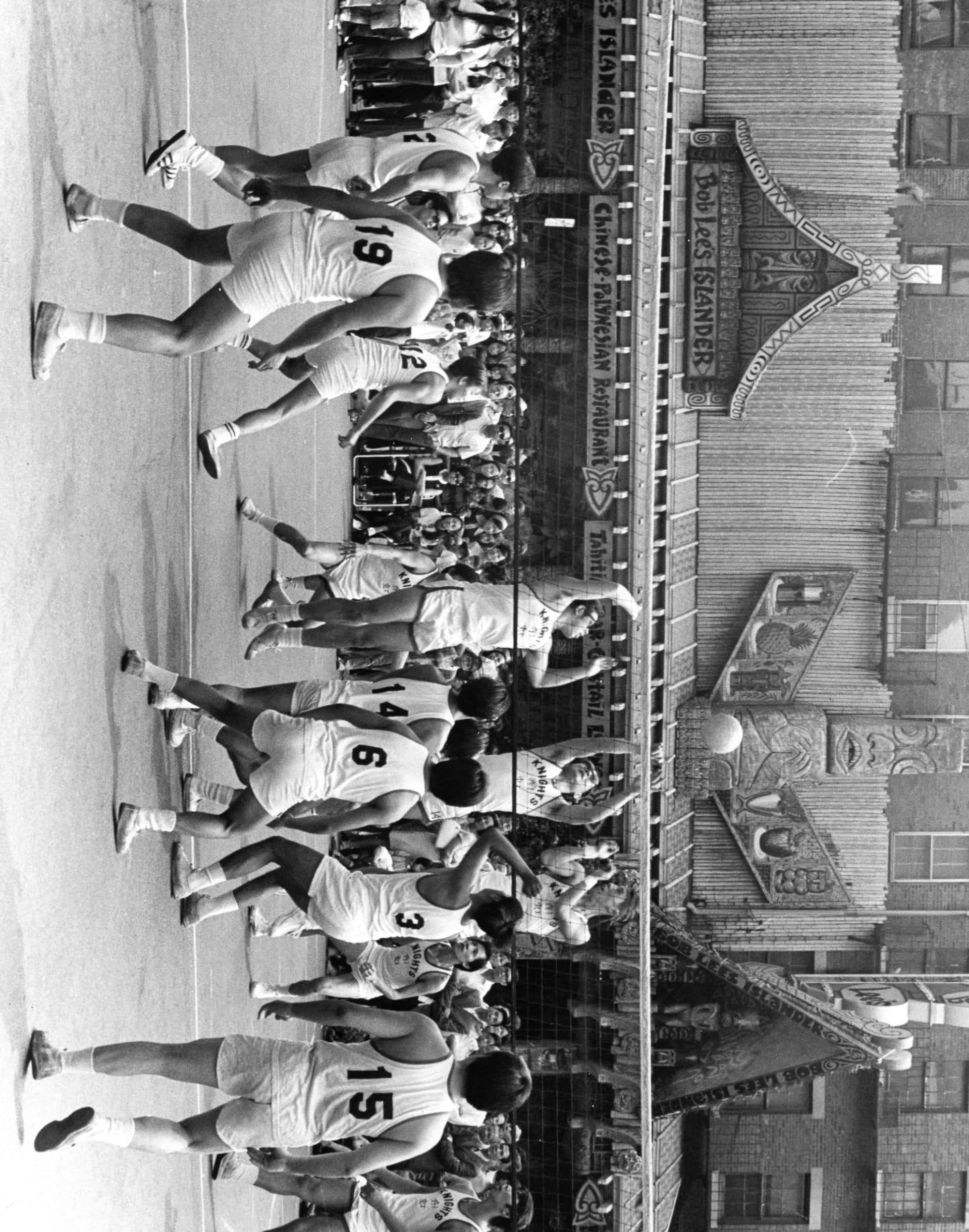

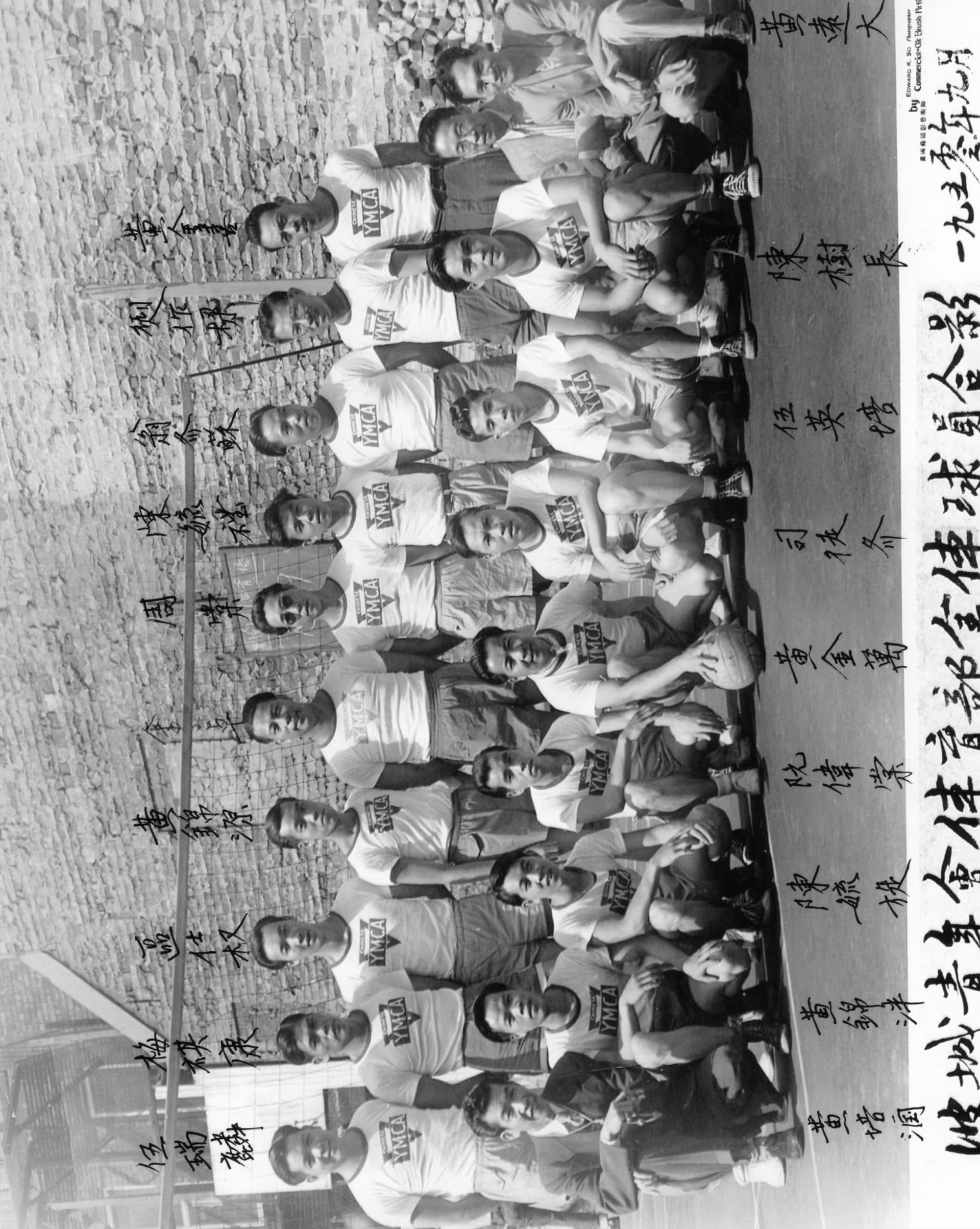

9-man is an urban adaptation of six-player or international volleyball with strong New England ties. In the 1930s, immigrants to Boston from Toisan in southern China began playing the game on streets and alleyways behind the laundries where many of them worked. They'd string rope across poles to create nets and fashion volleyballs from rolled up towels.

“It was a game that, unlike some of the organized sports of the era, could be really installed anywhere,” says filmmaker Ursula Liang, who directed the award-winning documentary “9-man” in 2014.

Because laws restricted immigration in the U.S. and Canada, the Chinese immigrant population was mostly male. They often lived in isolated communities and were limited to jobs that Liang said were considered "feminine," like cooking in restaurants or doing laundry.

Liang said the first 9-man competitions on the East Coast began as a way for players to learn about how Chinese people were faring in other cities.

The first annual tournament took place in Boston in 1944, according to the Chinese Historical Society of New England. Later, clubs in Chinatowns across the U.S. and Canada rotated hosting duties.

Almost a century after it began, the game's traditions endure. This year, however, due to rising costs and the tourney's increasing popularity, Boston organizers chose a location in another city — one without a Chinatown.

Instead of its usual spot on the asphalt courts of Reggie Wong Memorial Park in Chinatown, the North American Chinese Invitational Volleyball Tournament will be at the indoor larger exhibition center in Providence to accommodate 135 teams.

“Providence presented a good opportunity in terms of cost effectiveness. It's indoors, it's controlled. It's not as expensive a city as Boston to stay,” said Bobby Guen, one of the organizers and head coach of the Boston Knights.

Guen is a dentist in Brookline, but in volleyball circles he's better known as an “OG” of 9-man. Born and raised in Chinatown, Guen started as a Knights player 50 years ago. He said players today still embrace competing on the streets of Chinatown, because the game and its distinct court offers a drama and unpredictability that’s unlike other sports.

“We're not in a controlled indoor environment with air conditioning, no lights, no wind or whatnot," said Guen. "It goes back to the roots — to fall on the asphalt while diving for a ball and have the wind affect your service."

The rules of 9-man

At a recent regional competition in Everett, Guen looked out onto a parking lot where several courts were being drawn up.

One of the teams arrived in a truck and got stuck driving over a jersey barrier. “That’s Chinese style. Just back it up and go away. That’s 9-man culture right there,” he said, laughing.

9-man fans filed into the lot, setting up canopies and coolers on the edges of the court. Bright yellow tape on asphalt served as boundary lines.

The differences between 9-man and six-player international volleyball only start with the extra three players on each side. The courts are oversized, the net is lower and the players don’t rotate. This creates a more aggressive and chaotic game, where teams can deploy up to five or six attackers and confuse defenders at the net with quick, deceptive moves.

“It's definitely faster-paced, different positioning, different footwork. And just like, watching the game itself is completely different than sixes,” said Brandon Ho, 18, who plays for the Boston Rising Tide.

9-man also has its own rules about who is eligible to play. Half a century after the sport took hold in the U.S., the North American Chinese Volleyball Association introduced a rule in 1991 stating that two-thirds of the players on court must be “100% Chinese,” and the remaining players must be of Asian descent.

Liang, the filmmaker, says the sport did not start out with ethnic eligibility requirements, but those rules came to exist in the context of a broader discussion about the assimilation of Asian Americans in the U.S. 9-man helped create more opportunity for Asian American men in the world of sports.

"There's always been this feeling or this stereotype that Asians men's bodies are not capable of doing athletic things," said Liang. "We're bombarded with imagery and jokes about what their bodies could do. And if you're constantly facing those things, what a beautiful thing to be in a space where nobody even questions that."

For some, the strict eligibility rules carve out a protected space for Chinese and Asian Americans, and preserve a tradition passed down each generation.

Matt Mok, of Needham, is now in his sixth season playing for the Boston Hurricanes. He says, after growing up in a predominantly white school district, 9-man helps him stay connected to his cultural roots.

“Overall, I felt like an outcast, so coming here over the summer and just being able to be around people that are the same race as me is really good for me,” he said.

Mok was introduced to the sport by his father, and he hopes to pass his affection for the sport down to his future children. Until then, he comes home from UMass Amherst each summer break to play. Many 9-man devotees block off their summer calendars, often to the chagrin of family members.

"Divorces happen because of 9-man, because they never took time to take the families anywhere until after Labor Day," Guen said.

Martha Wu, of Wellesley, said the sport has been a meaningful way for her son, who is multiracial, to connect with his Chinese heritage.

“I love the history behind it, and I love the fact that it is really primarily all Asian, even though they can have the three of the nine who are not 100% [Chinese] like my son, thankfully,” said Wu.

In addition to the rules keeping non-Asians out, women historically have not played 9-man. Though, there are no rules prohibiting women from playing. Many 9-man clubs have women’s teams, but they follow international, six-player rules. The ethnicity requirements still apply.

For coaches of men's and women's teams, the eligibility rules can be onerous. When players need to be substituted onto the court, the coach has the added consideration of weighing a person's ethnicity.

“I completely understand the tradition of it. With all the segregation and discrimination that was going on in the United States, they wanted to create that safe space for Chinese Americans to play the sport that they love,” says Chelsea Hu, a player and women’s coach for the Boston Hurricanes.

But Hu supports some easing of the rules, in recognition of both the talent of individual players and the broadening of the Asian American community.

“America is a mixing pot, so it's just going to get more and more diverse," Hu said. "So I think that it would make sense in the future to open that rule up a little bit more."

While there are currently no plans to change the rules, Guen says 9-man, like other American traditions, will evolve.

“At 77 years on this tournament, we are older than the National Basketball Association," he said. "You look at the NBA, you look at 9-man. There's going to be changes."

Ahead to the big tournament in Providence, Guen is looking forward to long-awaited chances to socialize and reconnect with old friends. Beyond three days of nonstop volleyball matches, the event includes a side room for cards and mah-jong, a tile-based game. Teams gather for banquets in the evenings.

“The problem, of course, is there are no Chinese restaurants big enough there,” said Guen, “but there’s other cultures.”

The 77th annual 9-man tournament kicks off Saturday with the first serve at 8:30 a.m. and ends on Monday evening, when one team gets to bring home a year of bragging rights to their home city's Chinatown.

WBUR's Vanessa Ochavillo contributed this story.

This segment aired on September 2, 2022.