America’s Immigration Amnesia

Despite recurrent claims of crisis at the border, the United States still does not have a coherent immigration policy.

In the early 2000s, Border Patrol agents in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas were accustomed to encountering a few hundred children attempting to cross the American border alone each month. Some hoped to sneak into the country unnoticed; others readily presented themselves to officials in order to request asylum. The agents would transport the children, who were exhausted, dehydrated, and sometimes injured, to Border Patrol stations and book them into austere concrete holding cells. The facilities are notoriously cold, so agents would hand the children Mylar blankets to keep warm until federal workers could deliver them to child-welfare authorities.

But starting in 2012, the number of children arriving at the border crept up, first to about 1,000 a month, then 2,000, then 5,000. By the summer of 2014, federal officials were processing more than 8,000 children a month in that region alone, cramming them into the same cells that had previously held only a few dozen at a time, and that were not meant to hold children at all.

As the stations filled, the Obama administration scrambled to find a solution. The law required that the children be moved away from the border within 72 hours and placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services, so they could be housed safely and comfortably until they were released to adults willing to sponsor them. But HHS facilities were also overflowing. The department signed new contracts for “emergency-influx shelters,” growing its capacity by thousands of beds within a matter of months. Government workers pulled 100-hour weeks to coordinate logistics. And then, seemingly overnight, border crossings began to drop precipitously. No one knew exactly why.

“The numbers are unpredictable,” Mark Weber, an HHS spokesperson, told me in 2016, just as another child-migration surge was beginning to crest. “We don’t know why a bunch of kids decided to come in 2014, or why they stopped coming in 2015. The thing we do know is these kids are trying to escape violence, gangs, economic instability. That’s a common theme. The numbers have changed over the years, but the themes stayed the same.”

The cycle repeated itself under President Donald Trump in 2019, and is doing so again now. And as border crossings rise and the government rushes to open new emergency-influx shelters, some lawmakers and pundits are declaring that the Biden administration is responsible for the surge. “The #BidenBorderCrisis was caused by the message sent by his campaign & by the measures taken in the early days of his new administration,” Marco Rubio tweeted last week. The administration is “luring children to the border with the promise of letting them in,” Joe Scarborough, the Republican congressman turned cable-television host, told millions of viewers during a recent segment.

But for decades, most immigration experts have viewed border crossings not in terms of surges, but in terms of cycles that are affected by an array of factors. These include the cartels’ trafficking business, weather, and religious holidays as well as American politics—but perhaps most of all by conditions in the children’s home countries. A 2014 Congressional Research Service report found that young peoples’ “motives for migrating to the United States are often multifaceted and difficult to measure analytically,” and that “while the impacts of actual and perceived U.S. immigration policies have been widely debated, it remains unclear if, and how, specific immigration policies have motivated children to migrate to the United States.”

The report pointed out that special protections for children put into place under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 may have shifted migration patterns by encouraging parents to send their children alone rather than travel as a family. But it found that blaming any one administration for a rise in border crossings ultimately made no sense—the United States has offered some form of protection to people fleeing persecution since the 1940s, and those rights were expanded more than 40 years ago under the Refugee Act of 1980.

This is not to say that President Joe Biden’s stance on immigration—which has thus far been to discourage foreigners from crossing the border while also declaring that those who do so anyway will be treated humanely—has had no effect on the current trend. Like other business owners, professional human traffickers, known as coyotes, rely on marketing—and federal intelligence suggests that perceived windows of opportunity have been responsible for some of their most profitable years.

For example, border crossings rose in the months before President Trump took office in part because coyotes encouraged people to hurry into the United States before the start of the crackdown that Trump had promised during his campaign. With Trump out of office, some prospective migrants likely feel impelled to seek refuge now, before another election could restore his policies.

But placing blame for the recent increase in border crossings entirely on the current administration’s policies ignores the reality that the federal government has held more children in custody in the past than it is holding right now, and that border crossings have soared and then dropped many times over the decades, seemingly irrespective of who is president.

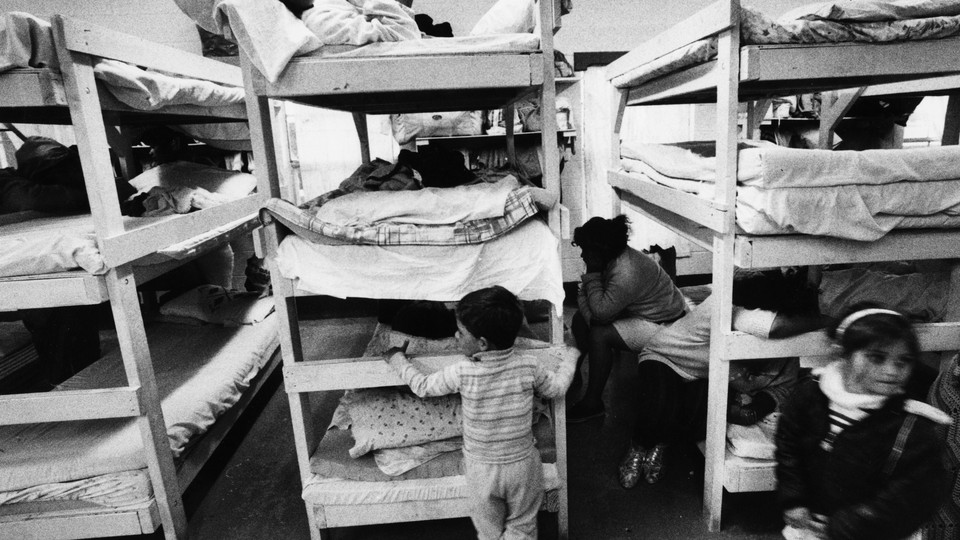

Given, then, that the movement of unaccompanied minors has long ebbed and flowed—we are now experiencing the fourth so-called surge over the course of three administrations—why do border facilities still appear overwhelmed? The answer, in part, is that the current uptick is simply getting more media attention. When Trump took office, in 2017, 13,000 children were sitting in Health and Human Services facilities, about 1,000 more than are in federal custody today; he did not receive any questions about the detention of migrants during his first press conference, and an online search did not turn up a single news story citing that statistic. The federal government, across multiple administrations, has also chosen not to meaningfully improve the conditions in border facilities: Children are still held in the same concrete cells that were used in the early 2000s, and the few larger facilities that the Department of Homeland Security has acquired since then to help expedite processing of children are just as austere as previous ones. They became infamous almost as soon as they opened, known as the places where children are held in what are effectively cages.

As I’ve covered this issue over the years, federal authorities have often vented to me during cycle peaks, complaining that facilities built for law-enforcement purposes had been hijacked to shelter children. During one of the recent surges, a Customs and Border Protection commissioner lamented to me that offices at ports of entry along the border were being converted into nurseries with TVs playing cartoons, and that the agency was hemorrhaging money to keep up with the need for diapers, feminine products, and crackers and juice. When I asked him why CBP didn’t just build additional, more family-appropriate facilities, he replied that such a project could send a message that would encourage even more people to migrate to the United States.

With his comment, the commissioner reiterated what many other officials I’ve talked with over the years have said: The issue is not that the federal government is unable to handle the large numbers of children crossing the border now—rather, that it has been unwilling to spend the money required to process children more safely and comfortably, because of a concern about optics. But if, as the Congressional Research Service report concluded, American policies are not the primary driver of migration, then the federal government may be needlessly avoiding changes that could improve how the United States treats the most vulnerable migrants.

The current backup at the border stems from more than insufficient infrastructure. Most Central Americans hoping to escape crushing poverty, gang and gender-based violence, and the increasing ravages of climate change are not eligible to apply for any existing American visa. Under current immigration law, which dates back to 1954 and was last updated in 1996, the only legal route into the United States for most of them is via obtaining asylum. This requires getting in line behind literally more than 1 million other people, and waiting on an arcane, individualized legal proceeding that requires multiple appearances before a judge and takes, on average, more than a year to complete.

American asylum protections were first established as part of an effort to atone for the rejection of Jewish migrants who’d fled Nazi Germany during World War II, only to be turned away from American shores. The program was also seen as a tool for promoting democracy abroad, offering a haven to people escaping Communist governments during the Cold War. The messaging campaign worked. The United States became known, even more than before, as a place where people could find both freedom from persecution and material opportunity. The American economy has grown more robust with the addition of foreign workers, a trend that shows no sign of changing.

But current immigration law does not, for the most part, acknowledge that many beneficiaries of humanitarian protections also become students and low-wage workers, who are a major portion of the American economy and are consistently in short supply. Because of the demand, farmers in New York and restaurateurs in Miami poach undocumented workers from one another; without new immigrants, they say, their businesses would tank. Yet the law treats people who migrate for educational or financial gain and those who seek humanitarian protections as if they are separate populations, when that is often not the case. And because the rules generally require that people who apply to migrate for work or school be relatively wealthy, the Central American migrants crossing the border today, who are not, pursue the only legal route available to them—asylum.

“The asylum system isn’t the right path for most people, but it’s the only path,” a career government official who has served in the past three administrations recently told me.

Many of these migrants are genuinely escaping harrowing circumstances. The Congressional Research Service report found that almost all unaccompanied minors have experienced some form of gang violence, much of which fits the definition of torture. And in recent years, immigration judges have declared that people fleeing attacks based on their gender or sexual orientation should also qualify for asylum status in the United States. Last summer, when I traveled to a working-class suburb of Guatemala City, the deep poverty was immediately evident in the crumbling homes I entered, where multiple generations crammed together under only partial, if any, roofing. People I interviewed shared stories of recent murders in their neighborhoods as casually as if we were chatting about the weather.

But continuing to funnel hundreds of thousands of people a year through a broken, backlogged system does not appear to be working. The asylum process creates an incentive for people to exaggerate their stories, which harms the credibility of others’, and has resulted in people who needed protection being sent home to their death. The plodding asylum system, and the failure to acknowledge that its recipients are also part of the American economy, is the primary reason facilities along the border are full today, and will continue to get overloaded every time migration has one of its cyclical increases.

The Biden administration has begun to take steps to address this problem for young people by reintroducing the Central American Minors Program, which allows parents who are lawfully present in the United States to petition for their children to join them. But that program, created by President Barack Obama in 2014 and eliminated three years later by President Trump, has resettled only about 5,000 children, slightly more than half of the number who crossed the border just in the last month. Many of the children crossing the border now may not qualify, because they don’t have a parent already living in the United States.

The current fixation on whether the Biden administration will refer to what is happening at the border as a “crisis” reflects the general lack of perspective with which migration “surges” are generally treated. Moments at the border like this should by now be considered almost routine, but our collective short-term memory—sometimes exacerbated by media hyperbole—allows elected officials to capitalize on them for their own political gain. This misleading of the public also helps Congress dodge accountability for its role in retaining a system that has been outdated for decades. Every time migration spikes, federal officials must abandon their primary work to demand billions of dollars in emergency funds, in order to respond to events that were foreseeable.

In the past decade, Americans have come to take for granted that Congress is too divided to pass any meaningful legislation—but that forgone conclusion could be revisited. Setting immigration policy is a congressional responsibility. In recent years, when Barack Obama and Donald Trump each attempted to take control of the issue from the legislative branch, they ended up in court, facing state governments accusing them of executive overreach. Such presidential efforts amount to mere stop-gap measures, which inevitably give way and allow the cycle to continue.