When Democrat Sri Kulkarni started campaigning in the deep-red Texas district once represented by Republican House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, consultants told him not to even bother trying to get the district’s Asian-American vote.

“I was told, ‘Don’t chase after Asian voters, they don’t vote,’” Kulkarni said in a recent interview with Vox, adding: “Maybe they don’t vote because we don’t bother.”

Kulkarni, a 40-year-old former foreign service official under the Bush and Obama administrations, is doing the opposite of what the consultants told him. “Why don’t we try reaching out in other languages, not just English?” Kulkarni thought. He’s running a campaign with volunteers speaking to voters in 16 languages — aggressively trying to convince the district’s Asian-American voters to cast their ballots for him.

The district sits in the Houston suburbs, a rapidly diversifying part of Texas. The non-Hispanic white population has fallen to 40 percent, while the Asian community now makes up nearly 20 percent of the district.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13341647/AP_18221832932055.jpg)

It’s a simple premise: greeting a voter in his or her native language builds a relationship with that voter and opens a door to the community. Kulkarni already proved it worked in the primary, emerging on top in a field of five candidates. His campaign’s internal numbers suggested their outreach had dramatically increased Asian-American primary turnout, from 6 percent in 2014 to 28 percent in 2018.

“This thing that was a waste of time resulted in a 12-fold increase in people coming out in the Asian community,” Kulkarni told Vox.

Winning against Republican Rep. Pete Olson on Election Day will be tough. But Kulkarni and his campaign believe he has a fighting chance, and are buoyed by the nonpartisan Cook Political Report recently shifting the race to merely “Lean Republican.”

“I’d watch this one,” Cook’s Dave Wasserman tweeted.

Asian Americans are an important Democratic bloc. But turning them out can be tough.

Though Kulkarni appears to be proving the political consultants wrong, there was a reason they advised him not to chase the Asian-American vote.

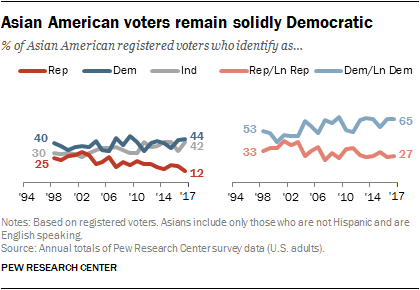

Asian-American and Pacific Islander voters are a rapidly growing demographic; nationwide, the Asian-American population grew 72 percent between 2000 and 2015. They also have a tendency to register as Democrats. But the Democratic Party has had a tough time successfully courting this bloc.

A recent Pew study found 65 percent of Asian Americans identify as Democrats or lean Democrat, compared to 27 percent who identify as Republicans or lean Republican. But they don’t turn out as often as white voters: In the 2016 election, 49 percent of eligible Asian-American voters cast ballots, compared to 64 percent of white voters.

In other words, while Asian-American voters are far more Democratic than other, similarly educated white voters, they don’t show up to the polls as reliably.

This makes outreach to Asian Americans a risky bet for candidates, especially those in conservative districts like Kulkarni’s. It’s a diverse demographic that speaks a wide array of languages and therefore demands more staff and volunteers. For a typical campaign, that can be a lot of investment for what has historically been a low return.

But if Kulkarni has figured out how to crack the code in TX-22, that could be good for Democrats’ future electoral chances, especially in rapidly diversifying suburban districts.

The Texas Democratic Party and other issues-based progressive campaigns have been reaching out to Kulkarni to learn more about his strategy.

“We think that’s exactly what other candidates and the party should be doing,” said María Urbina, the national political director for Indivisible. “They’re redefining what it means to engage with voters where they are.”

Campaigning in 16 languages

It all starts with a deep dive into voter data.

Kulkarni and others in his campaign combed the voter files of the district and separated out all the individual groups they could identify: Out of 85,000 registered voters, they broke up the list into Gujaratis, Punjabis, and Bengalis from India; Latino voters; and Vietnamese-American voters and voters from other Asian countries.

The plan was to pair a campaign volunteer from each ethnic group or country with each community — someone who could speak the language could make connections and convince people from these insular communities to vote Democratic.

“When you break it down into these smaller groups, each one is small enough to be managed,” Kulkarni said.

The campaign then follows up with campaigning in churches, temples, and community centers in the district.

“You campaign at places where immigrants gather,” he said. “They want you to talk to them, and they want you to listen to them.”

Just a simple greeting in another language can open countless doors, he added.

“That shows, ‘I see you’; that’s what we’re saying,” he added.

Kulkarni’s campaign style is very focused on something he calls “relational organizing” — volunteers put effort into getting family, friends, co-workers, or other people they know in the community to get out and vote.

“I think that by 2020, this is how all canvassing is going to be done,” he said.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61927829/AP_18221832903133.0.jpg)