Anthony Ocampo remembers how difficult it was to come of age as a queer, Filipino American man in the early 2000s, an era defined by rigid standards of beauty.

One of the companies that set those very standards was Abercrombie & Fitch, the subject of the new Netflix documentary “White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch.” With the heavy aroma of its cologne wafting from stores and its highly stylized wall-to-ceiling ads featuring muscular, shirtless, white male models, the brand set the bar for what was considered attractive for men at the time, said Ocampo, a 40-year-old former store employee featured in the documentary. At one point, he bought into it, too.

“There was a part of me, perhaps, that bought Abercrombie clothes to assert masculinity,” he told NBC Asian America.

But Ocampo said he was unexpectedly barred from working at the store — because, he was later told, he's Filipino — and he became one of several employees of color who joined a 2003 class-action lawsuit accusing the company of discriminatory practices. Abercrombie settled the suit in 2004, paying out $40 million, but never formally admitted guilt.

While Ocampo said he was happy to rail against the company’s racist practices two decades ago, the brand’s aesthetic affected his own sense of attractiveness for some time.

Today, Ocampo — a sociology professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona — is vocal about the toll that selling such a narrow idea of cool, sexy and masculine had on him and other Asian American men, a group that had already been portrayed as emasculated in U.S. media.

“What I realized after that Abercrombie incident is that when it comes to that version of masculinity, I’m completely ineligible to play the game,” Ocampo said. “I’m not white, no matter how hard I exercise, no matter how much I deprive myself of food — I was never able to achieve anything even in proximity.”

“I realized that as much as masculinity shaped my life, there’s nothing necessarily that we should valorize about masculinity,” Ocampo added.

Abercrombie’s current CEO, Fran Horowitz, said in a statement that the documentary is “not reflective of who we are now” but acknowledged that it had, in its past, taken “exclusionary and inappropriate” actions under former leadership that have since been overhauled.

“We’ve evolved the organization, including making changes in management, prioritizing representation, implementing new policies, re-envisioning our store experiences and updating the fit, size-range and style of our products,” Horowitz said in the statement. “We’re focused on inclusivity — and continuing that transformation is our enduring promise to you, our community.”

Featuring testimonies from former Abercrombie models, employees and executives, the documentary examines how the brand’s marketing and hiring practices in the late 1990s and early 2000s were meticulously constructed to produce an era-defining version of all-American “cool.”

But this vision of “cool” was discriminatory: Brown and Black employees accused the company of segregating them to the backrooms, and the company recruited conventionally attractive, thin, white college students from fraternities and sororities to work in the front of the store, according to the documentary. Meanwhile, workers of color, including Ocampo, were fired. The brand claimed it hired and fired on the basis of attractiveness — but the subtext was clear: People of color did not belong in Abercrombie’s exclusive culture.

Ocampo said that during his first year at Stanford University, in 1999, the clothing practically became the campus’s unofficial uniform. Surrounded by the Abercrombie aesthetic, Ocampo said he unintentionally bought into it, as well.

At the time, Ocampo was already struggling to attain Western standards of beauty. While he was proud of his Filipino background, purchasing the brand’s clothing meant purchasing a “proximity to whiteness” that was equated with attractiveness, he said. The brand’s homoerotic imagery also further inflamed his body image issues, said Ocampo, who noted he was not out at the time.

“In some ways, Abercrombie & Fitch, that white boy aesthetic, is like the pinnacle of not only for what was attractive in heterosexual environments, but also in LGBTQ environments,” Ocampo said. “That also, I think, affected me in a negative way because my perception of what the ideal gay man looks like was, even if the models weren’t gay themselves, it was that Abercrombie look.”

Ocampo acquired a few Abercrombie pieces on discount and ended up working at one of the stores during the winter season. He was promised a job if he wanted to come back in the summer, but when he returned, a brand representative told him they were unwilling to rehire him, he said.

“She didn’t give me a reason until I pressed,” Ocampo said. “She said, ‘Well, my manager says we can’t rehire you because we already have too many Filipinos working at this store,’ and that’s when I was stunned into silence.”

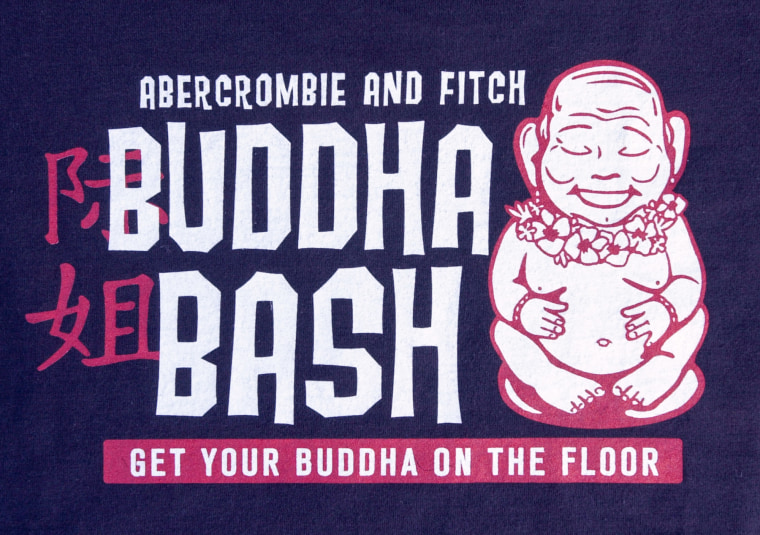

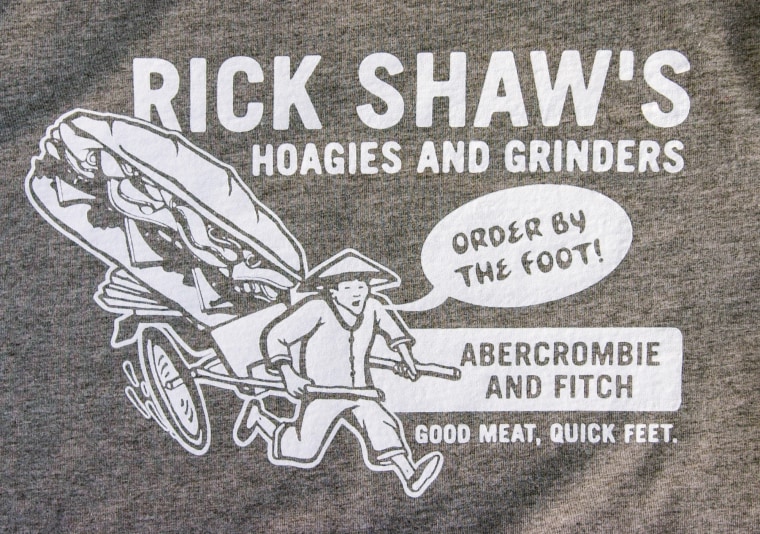

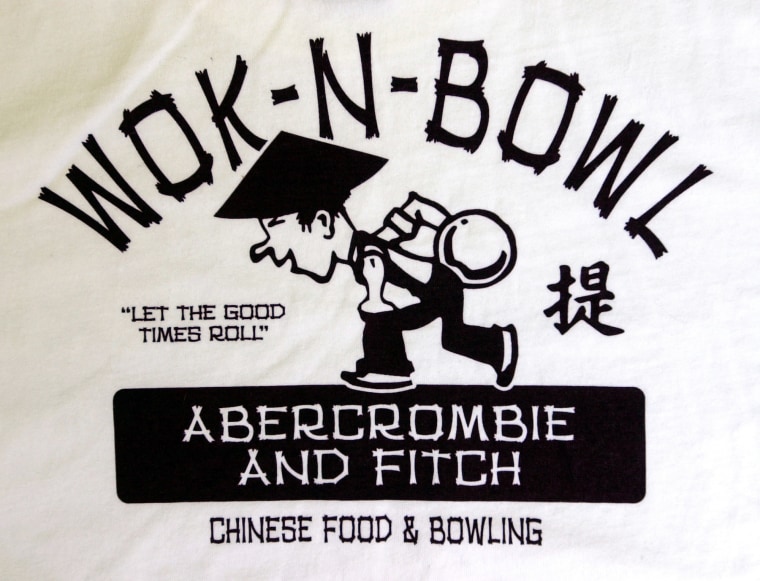

The brand’s aesthetic of exclusivity also permeated its marketing and seeped into its products. Logo tees that were wildly popular in the early 2000s featured several offensive designs. One of the most notorious was a T-shirt that featured racist caricatures of Asian men and read, “Wong Brothers laundry service — Two Wongs can make it white.” Another featured a smiling Buddha with a slogan that read, “Abercrombie and Fitch Buddha Bash — Get your Buddha on the floor.” Still another featured an Asian man in a rice-picker hat pulling a rickshaw.

“There were a lot of moments where Abercrombie as a brand hurt Asian men explicitly,” Ocampo said. “If you’re an Asian American man growing up in this time, and you don’t see any exposure to Asian men being desirable or attractive, and all you see represented in the most popular brand in America is this caricature of who Asian men are … that doesn’t really make you feel great.”

Ocampo said his experience with the brand still affects him in some ways today, saying it “dinged” his sense of self-confidence and made him feel less attractive. But it also set off a gradual, decadeslong journey in divesting from the importance of proving his masculinity.

“That was the first moment where I was like, ‘Masculinity can very much harm me,’” he said. “You can’t separate it out from whiteness and Americanness either.”

Brands like Abercrombie fed a deeply toxic culture in society that has yet to be erased, Ocampo said. He said he believes that, ultimately, masculinity remains a form of social currency. But it’s not one that people should uphold.

“I actually don’t think masculinity is something that we should strive for, because masculinity is often predicated on the oppression of women and queer people,” he said.