This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

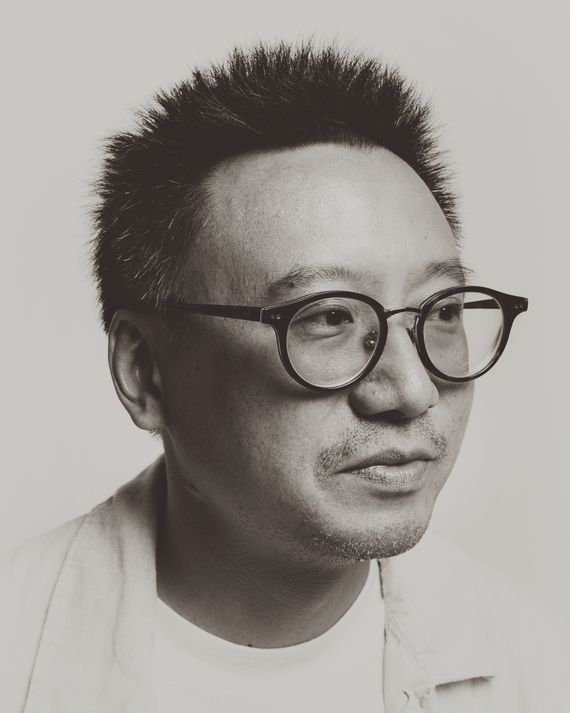

Hua Hsu entered the store with a box full of books. “I’ve reached an age where I realized I have more than I could possibly read,” he told me after dropping the titles with an appraiser at Unnameable Books in Prospect Heights, where we had agreed to meet this summer so he could make a quick sale before we began our interview in earnest. The proprietors clearly knew Hsu from previous visits, an unmistakable figure even in a KN95 mask, his hair shooting up in black needles from his high forehead like a stiff brush. He was told the haul would fetch him $70 in cash or $120 in store credit. “Store credit,” Hsu immediately responded, somehow failing to register that, in making this choice, he was just going to end up with more books.

Hsu, a staff writer at The New Yorker, is an inveterate collector — of books, yes, but also of music and movies, relics and memories. His new book, Stay True, is a memoir with a tragedy at its center: the killing of his close friend, Ken, during a robbery in the late 1990s, when they were students at UC Berkeley. But it is also a coming-of-age story that proposes an identity can be created through the careful curation of the galaxy of cultural artifacts swirling around the average American teenager. For the adolescent Hsu, this curatorial instinct found its purest expression in the zine, those xeroxed, stapled-together DIY magazines that long ago went extinct. “Making my zine was a way of sketching the outlines of a new self, writing a new personality into being,” he writes.

That may sound like standard fare for a young Gen-Xer (Hsu was born in 1977), but I’m not sure there’s ever been a book quite like Stay True. It is decidedly not an overt attempt to explain the Asian American condition, a genre popularized in recent years by Wesley Yang, Jay Caspian Kang, and Cathy Park Hong. Nor is it part of a rich tradition of immersing readers — and by this I mostly mean white readers — in an immigrant milieu like Anthony Veasna So. Its significance is so subtle that it might be lost on people who didn’t hang out with a lot of Asian kids when they were young, which, given how few Asian Americans there are in this country (we make up only 6 percent of the population), is nearly everyone. But if your friends parted their very straight black hair down the middle and shaved it around the sides, and wore baggy jeans and high-tops and listened to a lot of Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, then you will read this book and think, perhaps for the first time in your life, I know these guys.

Hsu and Ken form a kind of spectrum of Asian assimilation. The former, a child of Taiwanese immigrants, is uncomfortable with the white mainstream “at a molecular level” such that ordering pizza makes him feel as if he’s “playacting” as an American. The latter is the descendent of a Japanese family that’s been in this country for generations; he wears Abercrombie & Fitch, dates white girls, joins a fraternity, and is everywhere at home in the world. Yet their race can often feel incidental to the story. Hsu and Ken drive around in their cars. They smoke a lot of cigarettes. They argue about music and films. None of this should feel extraordinary, yet it does. They are both Asian and not, equally embodying the American side of that hyphenated ledger. “I was an American child, and I was bored, and I was searching for my people,” Hsu writes, sounding less like a marginalized minority than an everyman.

But because this is America, they can never escape their race, never fashion for themselves an identity that is truly autonomous, no matter how many underground bands and indie movies they collect. Hsu, who made his name as a pop-music critic but has increasingly devoted his attention to Asian American history and politics, trafficks in this bothness, his career evidence that, while it may not be possible or even desirable to transcend race, it doesn’t have to wholly define a person either. The voice in Stay True is not directed at “them” or “us,” whatever that might mean for a demographic composed of a myriad of ethnicities and cultures. As Hsu told me, “I don’t think it was written with any real audience in mind other than I would have liked to read this.” It is a characteristically modest claim that also feels like an evolutionary step for identity-inflected literature.

In person, Hsu exudes the same casual confidence that animates his work, speaking in finely constructed paragraphs. He is 45 years old yet ageless in the way that middle-aged Asian men can sometimes be. I could not detect a single wrinkle on his tawny face, and his clothes — a blue linen shirt with white stripes, gray Nike trainers with a fluorescent-yellow swoosh — were somehow both youthful and appropriate for a Brooklyn dad. Although he has lived in New York on and off for 15 years, he remains a Californian in demeanor: laid back, neither hot nor cold, navigating the video-game unpredictability of city traffic with aplomb. We drove to a record store in Red Hook, where once again everyone knew who he was. (“Your book’s coming out in September? We should have a party!”) He bought albums by Clifford Jordan and the Heptones before we set out for a place where we could talk. After wandering the neighborhood’s ragged edges on the waterfront, we settled on a table outside the old Fairway, looking out over the parking lot. He bought us a couple seltzers, then tried to explain to me what it meant, as a friend and as a writer, to stay true.

Hsu grew up in Cupertino at a time when Apple’s world-straddling dominance was but a gleam in Steve Jobs’s eye. His parents had come to the United States to pursue advanced degrees, part of the wave of so-called high-skilled Asian immigrants that followed the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, and they chose this corner of Northern California because it offered some of the comforts of home: friends, Chinese bookstores, bubble-tea cafés, Chinese food (“neck bones and chicken feet and various gelatinous things,” Hsu writes). His parents were not the relentlessly aspirational Asian immigrants of the popular imagination, those who force their children to master the cello and ace their standardized tests. “My parents are great,” Hsu tells a therapist in the book. “Unbelievably non-stereotypical.” Their home was filled with music (“They played Thriller so much that I assumed Michael Jackson was a friend”) and a tender, easygoing camaraderie. When Kurt Cobain, Hsu’s first great musical discovery, killed himself in 1994, his father wrote him a note that, in imperfect English, contains remarkable insight and foreshadows Hsu’s reckoning with the senselessness of Ken’s death: “That’s the dilemma of life: you have to find meaning, but by the same time, you have to accept the reality.”

Still, there is something sad about his relationship with his parents, a rift born out of not a lack of affection but the insurmountable fact that they come from different cultures — the ancient conundrum of the immigrant family. “My parents grew younger in Taiwan,” he writes of their regular visits to the homeland. “The humidity and food turned them into different people.” This glimpse of their true selves underscored that in Taiwan he was a stranger. At one point, his father, an engineer stuck in middle management like so many Asian white-collar workers in America, returned to Taiwan to take a job as an executive now that his country had caught up economically and boasted its own opportunities. The letter he wrote to his son about Cobain came over a fax machine, one of many period details that situate Hsu’s story firmly in the 1990s while symbolizing the distance between people whose lives have been marked by the ebb and flow of globalization.

The second-generation immigrant’s story makes explicit what we all know: that becoming oneself is a lonely journey undertaken, with any luck, with a little help from our friends. “I believed I had nothing in common with these people and their stories,” Hsu writes, referring to his mother’s efforts to acquaint him with Chinese history and other tales from the old country. Instead, he followed the path laid out by Cobain, discovering the bands Cobain had once discovered — the Raincoats, the Vaselines, Mudhoney — and credited with saving his life. “I chose to consume culture that I thought was really esoteric because I felt different, misunderstood,” Hsu told me. The effect was to compound his alienation from the white mainstream, but one of the refreshing aspects of Stay True is that the protagonist does not yearn to be accepted; rather, he develops a healthy disdain for the society that has made him feel like a foreigner, epitomizing the ’90s ethos that the white mainstream was pathetically uncool.

So it’s all the more curious that one of his best friends at Berkeley turned out to be a very white sort of Asian — what we called “Twinkies” back in the day and who now go by monikers like “San Francisco whites” (Asians with tech money who voted to recall the city’s progressive district attorney Chesa Boudin). Ken was popular and handsome. He liked Dave Matthews Band. He took up swing dancing after watching the movie Swingers, about a couple guys on an epic quest to get laid. The book has some very funny scenes of Hsu being embarrassed by his extremely basic friend, rolling up the car window so no one can hear Ken blasting “Crash Into Me” on the stereo. For whatever reason, this well-adjusted bro saw something in Hsu, a misfit who was reading Giant Robot magazine and rifling through the stacks at Amoeba Music and being militantly straight edge. “A mismatched pair moving through the world,” Hsu writes, a line that reminded me of my own mismatched friends in school, perhaps the last time in life when it is possible to bond with people who differ from you in all the ways that supposedly matter: taste, interests, politics.

Ken also had depths that surprised Hsu. He inhaled the tapes Hsu made him. “I joked that he was probably the only frat boy in America to like Belle and Sebastian’s meekest tunes,” Hsu writes. Ken was also aware that Asians are a special sort of minority, falling outside the white-Black dichotomy that has defined race relations in this country. They are not victims, comparatively speaking, and only tentative members of that category “persons of color”; nor are they beneficiaries of the kind of racial privilege afforded to whites. “I am a man without a culture,” Ken tells Hsu, an on-the-nose admission for a guy whose idea of a good time was listening to Pearl Jam. Perhaps that is why he was attracted to Hsu, a kid who had a culture all his own and was entirely self-sufficient when it came to arbitrating what was cool and what was not. (Hsu rejected this characterization in his conversations with me, saying he merely took his cues from people older and cooler than him.) Hsu’s obsessions amounted to a kind of code. He was once robbed on the street, but his would-be muggers chased him down to give him his wallet back — there was little in it but a Blockbuster card and a creased photo of Björk.

They were both flourishing. Ken wanted to go to law school and tried to start a club called the Multicultural Student Alliance. Hsu got into underground rap and fell in love. He also had a political awakening, filling his course load with classes on Asian American studies, and wrote for the Asian American campus papers Slant and Hardboiled. Who knows how their lives would have turned out if a gang of petty thieves hadn’t waylaid Ken one night? They took his bank cards, put him in the trunk of his car, and shot him through the back of the head.

Hsu was already a writer, but Ken’s murder gave him a person to write for. In the years that followed, he found himself in a state of “constant occupation,” that time-honored panacea for the bereaved and the heartbroken. He went to Harvard for grad school, then got a job teaching literature at Vassar. (He will begin a new position at Bard this fall.) He wrote on the side: reviews of albums and books, sometimes for as little as $40 a pop, for magazines and websites (Urb, Knowledge, 360hiphop.com) that largely no longer exist. One day in the early aughts, he sent a blind pitch to The Village Voice, and on the other end of that email was an editor named Ed Park. Park eventually commissioned a 150-word review of a history of hip-hop culture called Yes Yes Y’all, inaugurating Hsu’s association with the Voice, then the hippest paper in town. He was part of a loosely connected group of young writers — Jon Caramanica, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jeff Chang — who are now established names. He started freelancing for The New Yorker in 2014 and became a staff writer in 2017.

When I told Hsu he had an enviable writing career — one based on his various interests in which he wasn’t expected to write about being Asian all the time — he noted that back when he first started publishing, “there was no real appetite” for the kinds of identity-based personal essays that are now so common, so it wasn’t even an option for him. He also pointed out that the Voice was the kind of place where minorities and other weirdos often got their start as writers, yet another reason to bemoan the death of the alternative press. “There were the predominantly white magazines, the classic prestige titles that were run by white people mostly,” he said. “But there were places like The Village Voice, Vibe magazine, Urb, music magazines where the staff were actually way more diverse than most staffs today even in this era of concerted efforts to diversify. So there were ways that you could write from a perspective that was clearly, if not Asian American, on the side, in the margins.”

Hsu does not consider Stay True a departure from his body of work as a critic. “I’ve written about all these different subjects, but they all kind of orbit this thing I’ve never written,” he said of the book’s origins. While he has been writing parts of Stay True since Ken’s death, it fully came together after he got a fellowship at the Cullman Center at the New York Public Library in 2019. Every day, he would sit in an office he had plastered with photos and posters from his days at Berkeley — “I needed to really return to the aesthetic,” he said — and type up the manuscript on an old Hewlett-Packard desktop. The initial responses from friends and family were not great. “This is just getting too depressing,” his wife said of his account of Ken’s death. So he started incorporating the quotidian details of his crew driving to 7-Eleven and eating donuts and watching blaxploitation kung fu flicks, giving the book its beautifully grained realism. “As I was writing it, there would be moments of intense joy,” he said, “because I would feel like I was hanging out not just with Ken but all of our friends.”

Hsu wears his politics lightly, but the book is shot through with glimpses of a person who is deeply invested in notions of community and solidarity. At Berkeley, he volunteered to tutor Southeast Asian middle schoolers. He also tutored prison inmates (one of whom, Eddy Zheng, would become the subject of a profile Hsu wrote for The New Yorker). This is not the behavior of a typical college kid, let alone a mustache-twirling aesthete, though he resists the idea he’s a political writer, saying he was more interested in forging through writing “a renewed commitment to one another, maybe a renewed commitment to a world beyond yourself.”

In Stay True, he writes, “To me, Asian-American was a messy, arbitrary category, but one that was produced by a collective struggle. It was a category capacious enough for all of our hopes and energies.” When I told him that I thought this category was too capacious, that the increased visibility of Asian American communities in recent years had revealed some perhaps intractable fissures, and that some Asians were dismayingly conservative on issues such as crime, Hsu maintained that it was still useful to think of Asians as being a group with distinct interests. He cited the Amazon teen rom-com series The Summer I Turned Pretty, about a mixed-race white-Asian family vacationing in a Cape Cod–type place called Cousins Beach, as a reason to be optimistic about what Asian American identity politics could achieve. “It isn’t really about them being Korean American at all,” he said. “They just happened to be Korean American.”

“See, I think you could do a critical read of that particular show being like, ‘Asians are just becoming white people,’” I responded.

“I mean, look, I’m not trying to die on that hill,” he said, laughing. “I think that’s definitely how I would generally feel.”

Interestingly, Stay True presents Ken’s death as a “freak occurrence” with few if any racial implications. When one editor at Hardboiled suggested looking into Ken’s death as a possible hate crime, Hsu bristled. “I was mostly upset that my colleague had tried to slot Ken’s death into a broader context — one beyond my understanding and control,” he writes. “I was unwilling to relinquish him to some greater cause.” Hsu became obsessed with a quotation a basketball player gave the school newspaper about a campaign against ethnic-studies programs — “It’s fucked up the way it is sometimes” — writing it over and over in his journal as if this offhand comment contained within it the absurdity of an indifferent universe.

I told Hsu that, if you were to just read the dust jacket of his book, you could be forgiven for presuming it’s about a fully assimilated Asian man who was nevertheless cut down in his prime because of his race — a salient idea given the number of hate crimes that were committed against Asians during the pandemic. It seemed remarkable to me that Hsu would so forcefully yank that narrative out of the running even if the evidence was thin that a hate crime had been committed. “It’s ironic,” he conceded. “I think, in that moment, I didn’t want him to turn into some symbol. But clearly he did represent certain things to us, and he does in the book too.”

In general, he seemed surprised and a little uncomfortable with the fact that I, like his former colleague at Hardboiled, was going to put him and his memoir in that broader political context. “The part that’s personally bewildering is how my book, which I began writing for somewhat intimate or deeply personal reasons, now enters into” a discussion about Asian American identity, he later wrote in an email. “It’s still strange (and humbling) to think that I have written myself and my friends into characters that other people might feel a way about.”

There were times when it felt as if Hsu, out of modesty or good manners, wasn’t being entirely straight with me, as if he were preventing a fiercer intelligence from blazing into view. When we left the record store in Red Hook, he asked me what I had gotten; I showed him that it was Destroyer’s Have We Met, the cover featuring Dan Bejar in full coked-out lounge-singer mode. It might be entirely my imagination, but I thought he hesitated a moment, and a line from Stay True flashed across my mind: “I saw a bad CD collection as evidence of moral weakness.” Was Bejar kind of basic? Yeah, he was, actually. Was I … uncool? Yes, decidedly so. Hsu said something like, “Oh, nice, I haven’t really listened to his newer stuff,” which could have meant anything.

It was comforting to remember that Hsu is a teacher by profession, accustomed to people saying and doing embarrassing things all the time. There is a forbearance in his manner that seems to come from repeated exposure to students who aren’t sure yet exactly what they think or feel and who in turn give him valuable perspective. “I’m around young people a lot,” he said, “and it’s been good because I always have to remind myself that even if I liked the time period that I grew up in, they don’t have to give a shit about it, you know?” The respect he shows them is also, I think, a way of staying true to the person he once was.

“Stay true” is how Ken used to sign his emails, an abbreviation of “Stay true to the game,” the kind of silly phrase boys bandied about in the 1990s — borrowed from hip-hop — that over time crystallizes with new meaning. In one sense, it means you should stay true to your friends, and Hsu’s book is touching evidence that he has not forgotten the people who made Berkeley the formative experience of his life. But it also means being true to yourself, and that is a trickier concept. Is the self an innate entity — your essence, your soul? Is it contained in your roots, trailing all the way back to the motherland? Or is it created the way a book is made by its author? And if you’re Asian, is it created for you by whatever people think the shape of your eyes and the color of your skin represent? Hsu’s book is about the interplay of these different versions of the self, the suggestion being that, inevitably, there are limits to self-invention. What’s admirable about this position is that he has not only accepted those limits but enjoys them — enjoys being Asian American, which is harder to do than you might think.

Finally, there is the question of whether it is possible to stay true to your friends and yourself at the same time — whether, to truly become yourself, you have to leave others behind. There is a sense that, in writing this book, Hsu has managed to both express himself more fully than he ever has before and finally let Ken go. Hsu admits that, if Ken had lived, they might have drifted apart, and it is impossible to say what Ken would think of this book that has been written in his honor. It even features him on the cover with his very straight black hair parted down the middle and short around the sides, pointing a black camera that covers his face at the viewer — an image that conveys the ghostly gaze Hsu feels is always upon him. My guess is that, behind the camera’s great eye, Ken is grinning.