Sign up here to receive The Yappie's weekly briefing on Asian American + Pacific Islander politics and support our work by making a donation.

When Paul Hoang worked as a therapist in Chicago, he was one of the few providers in Illinois at the time who spoke Vietnamese.

As he navigated the counseling space, he witnessed the consequences of not having culturally informed and language translation services available for clients—one of whom was misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and put on medication that left him severely sedated for years.

That Vietnamese man’s diagnosis was based on translations between the provider and the client’s daughter, who was only 8 years old.

“Having a minor who's not versed in medical terminology and providers who did not understand the culture or the context, [meant] they didn't know how to ask follow-up questions that were appropriate to help them inform their care,” Hoang said.

It’s just one example of what happens when people cannot access culturally informed care, said Hoang, who has now worked as a licensed clinical social worker for over 20 years.

Vietnamese people and other Southeast Asian immigrants and refugees like Lao, Hmong, and Cambodian Americans face higher rates of mental health challenges, but access mental health care at significantly lower rates than other ethnic groups due to a variety of factors including cultural stigmas, a lack of providers who speak their language, and financial accessibility.

A history of displacement

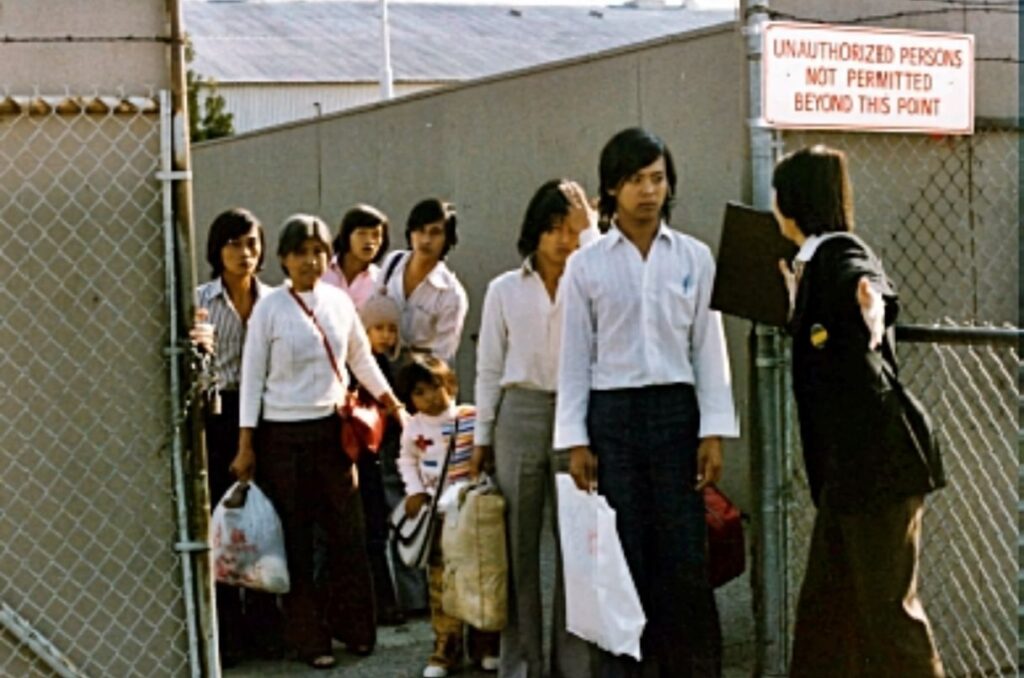

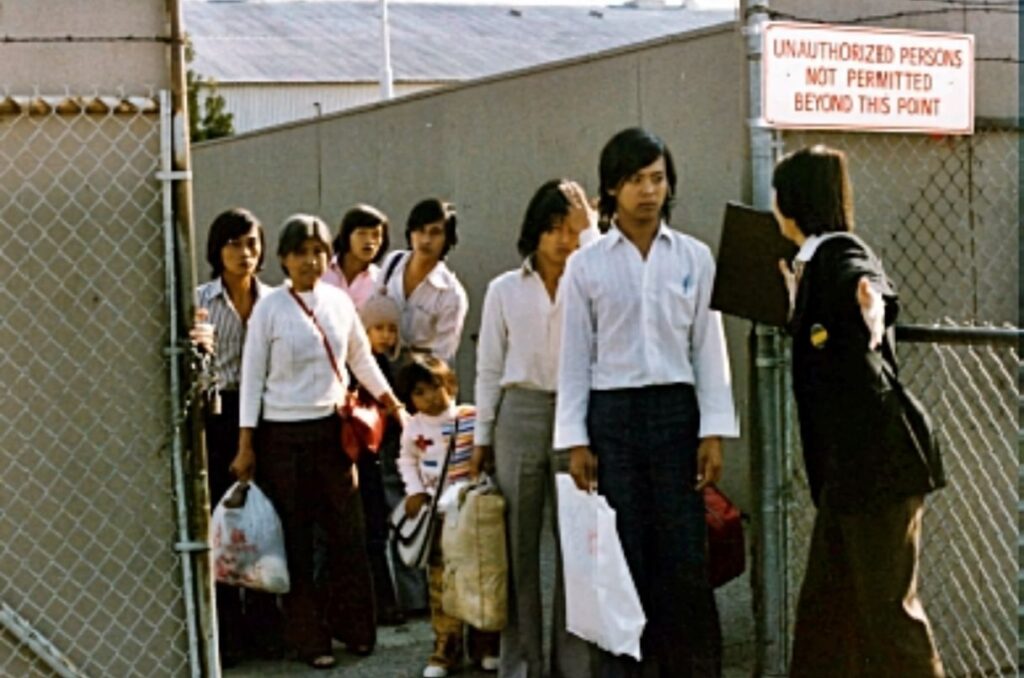

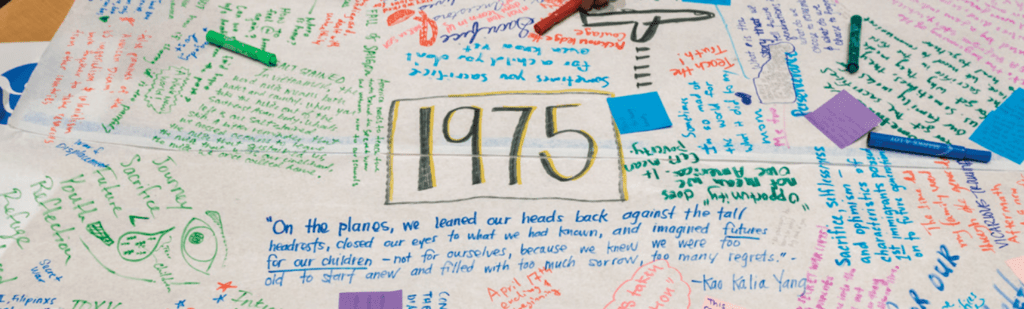

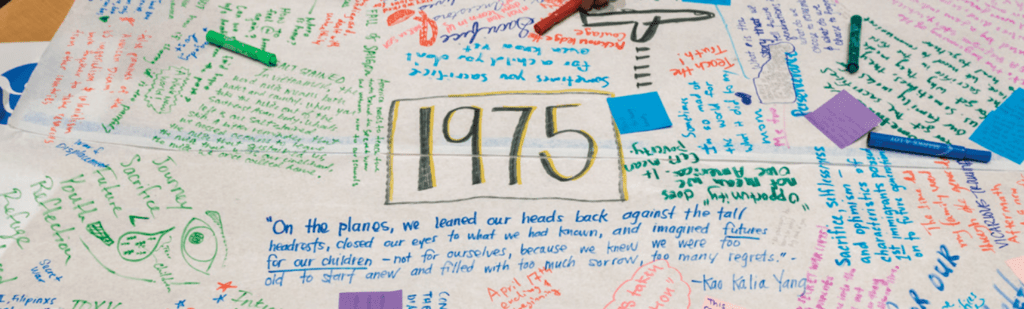

Southeast Asians began resettling in large numbers to the United States in 1975, in the fallout from the Khmer Rouge genocide, the U.S. Secret War in Laos, and the Vietnam War. Numbering over 1.1 million refugees across 30 years, Southeast Asians became the largest refugee group in America’s history.

Finding safety amid war and genocide, Southeast Asians experienced immense grief, loss, displacement, and isolation—unsure if friends and family members who were left behind were still alive.

In a 2019 survey conducted by the Southeast Asian Resource Action Center (SEARAC), over 60% of respondents related their mental health conditions to their experiences of trauma and intergenerational trauma.

But many Southeast Asian Americans lack access to mental health resources. For example, 57% of Cambodian women reported in a study of cervical cancer control that they experienced difficulty getting medical care because of obstacles to finding interpreters. Other barriers like cultural stigmas also cause Southeast Asian Americans to access mental health care at low rates.

As the number of Southeast Asian immigrants, refugees, and their children continues to grow in the United States, they’re finding their own ways to care for half a decade of wounds left from the wars and displacement in Southeast Asia.

Culturally adaptive care

After his experiences providing care in Chicago, Hoang moved to California and founded the Moving Forward Psychological Institute, a community clinic based in Fountain Valley that provides therapy and other social services for community members in English, Vietnamese, and Spanish.

Hoang said his work is rooted heavily in cultural adaptation and cultural humility. For him, that means being cognizant of the different cultural backgrounds that might inform a person’s experience and including that as a part of their mental health care.

“When we work with someone, we always ask that person to help us understand: What do you mean when you say this? Can you help me understand how you understand your experience?” Hoang said. “In that way, we don’t project any of our own assumptions onto that person.”

In his work with Vietnamese community members, Hoang said he focuses on three methods of care: solutions-focused therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and mindfulness.

Oftentimes, Vietnamese people experience multiple layers of trauma at once—touching on one layer may trigger other layers and make the healing process more difficult, Hoang said. Approaching growth by identifying ways to make improvements in a person’s everyday life can make therapy care more accessible and less daunting.

Applying acceptance and mindfulness-based psychotherapies with cultural contexts in mind may make them more effective when applied to Asian Americans because of their ideological roots in Asian philosophies, according to a study published in the National Library of Medicine.

Many East Asian and Asian cultures value the collective—but as it’s been applied in the United States mindfulness practices have been rooted in individuality and reflecting on one’s inner experience. Catering mindfulness to collective thinking rather than individual thinking can better tailor mental health care services to people’s needs, Hoang noted.

With solutions-focused therapy, Hoang said he helps clients manage the impacts of their mental health struggles in their daily lives, like practicing steps to manage anxiety. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on how a person’s mood, thoughts, and behavior are all interrelated, which Hoang says empowers people to know that they can make change in their lives.

Transcending language through art

Ha Tran, a community support group manager who works for Asian Human Services, provides art therapy for immigrants and refugees in the Chicago area, a practice she said transcends the barriers language sometimes imposes on people, particularly immigrants and refugees.

Tran came to the United States as a refugee from Vietnam when she was 7 years old. As a child, Tran did a lot of drawing and often found herself coming back to one drawing—a picture of her home in Vietnam. As she grew older, Tran said she realized that expression through drawing and writing became a form of therapy.

“The art piece [is] the vehicle for you to communicate, because a lot of things that we go through, that we think about, that we feel or experience—we can’t really verbalize it.”

— Ha Tran

For Tran, art therapy is a form of communication, one where people can connect with others and build self-esteem through visual arts, music writing, plays, and dance movement.

“It serves as a visual evidence for the person to see and feel some awareness of, ‘This is what's going on inside of me,’ without feeling directly like I'm exposing myself so much,” Tran said. “The art piece [is] the vehicle for you to communicate, because a lot of things that we go through, that we think about, that we feel or experience—we can’t really verbalize it.”

Studies have shown that art therapy and painting can be used to help people cope with depression and anxiety. Clients can express and vent their emotions by projecting them onto their art. In some Chinese group art therapy situations, the practice has promoted the recovery of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and improved social function.

Tran said group work and art therapy have worked well for her Vietnamese clients. By interacting in a group, community members can meet others who are going through similar experiences of feeling lost or displaced and isolated.

Tran said traditional one-on-one therapy services can be “sterile,” where the relationship between a client and a provider lacks a familial interaction that is valued in Vietnamese culture.

When they practice art therapy, Tran said people can be more present, leaving behind the thoughts and anxieties that can get stuck in someone’s head and instead bringing up other positive memories that allow them to reconnect with feeling joy.

“It's really about exploring and finding something new to make a person feel like, ‘I'm still worth something,’” Tran said. “That then allows them to have the energy, confidence and support to feel like, ‘Okay, I can face these challenges now.’”

The art of storytelling

Lao American healing activist Rita Phetmixay has been using storytelling as a form of healing for Lao and Lao Americans. Phetmixay created “Healing Out Lao’d” in March 2019, an online podcast that explores the stories of the Lao diaspora in English.

She describes the space as a “community practice space,” one that was inspired by her own mental health journey.

While studying for her master’s degree in Asian American studies at UCLA, Phetmixay said she started learning how to verbalize racism and recognize how it affected her in her daily life. But, while she was able to find the words for how oppressive structures impacted her, she said she lacked the tools to heal that trauma and was left with unprocessed anger.

“At that time, we were building community, we’re connecting other Lao folks,” Phetmixay said. “And the common theme was like, ‘Oh, you went through that, too? I went through the same thing.’”

With over 20 episodes so far, Phetmixay has covered topics in the Lao diaspora related to queer identity, fatherhood, processing grief, environmental justice, and more.

Using storytelling in this way, Phetmixay said, can help make healing and therapeutic practices more accessible because it only requires a device for listening. As she looks to the future of the project, Phetmixay said she hopes to make the podcast accessible in other languages as well.

“Stories that we tell [are] healing so that people know that they are not alone, because when you suffer in isolation, you continue to suffer from isolation,” Phetmixay said. “Part of this storytelling piece is making sure people know that, one, you're not alone. Two, you're seen, heard and validated. And three, you were born, out of love, and here to feel liberated—not confined.”

Solutions that last

While Southeast Asian Americans continue to find solutions for healing within their community, Hoang said individuals can initiate change in their own lives and circles by starting conversations about mental health and normalizing it.

Advocacy groups like SEARAC have also proposed potential policy responses to improving access to mental health care for Southeast Asians, including having state legislatures increase funding to the Department of Health Care Services to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate prevention and outreach materials or implementing early screening of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in public school systems to preemptively identify mental health conditions.

Other legislation has focused on addressing and limiting the detrimental impacts of inequitable health care access. Deportation disproportionately impacts Southeast Asians who carry the weight of trauma but struggle to integrate after resettling. The Southeast Asian Deportation Relief Act, which was introduced in the House in September, would ban the deportation of Cambodian, Vietnamese, and Laotian individuals who arrived in the U.S. before 2008—eliminating a key source of anxiety.

Hoang said recognizing symptoms of mental illness rather than allowing them to remain undiagnosed and untreated is crucial—especially for parents, as mental health issues most often become more noticeable and develop through the late teens and early 20s.

He related unspoken mental health issues to a water kettle, where the growing pressure inside as it heats up is like a person’s internal stress and pressures. Without a way to release that steam, the kettle bursts.

“The water kettle has both automatic off buttons when it reaches a certain temperature, and it has a spout to release the pressure,” Hoang said. “For our human body, we don't have that built in as automatic. We have to build it ourselves.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled Rita Phetmixay's name.

The Yappie is your must-read briefing on AAPI power, politics, and influence, fiscally sponsored by the Asian American Journalists Association. Make a donation, subscribe, and follow us on Twitter (@theyappie). Send tips and feedback to [email protected].