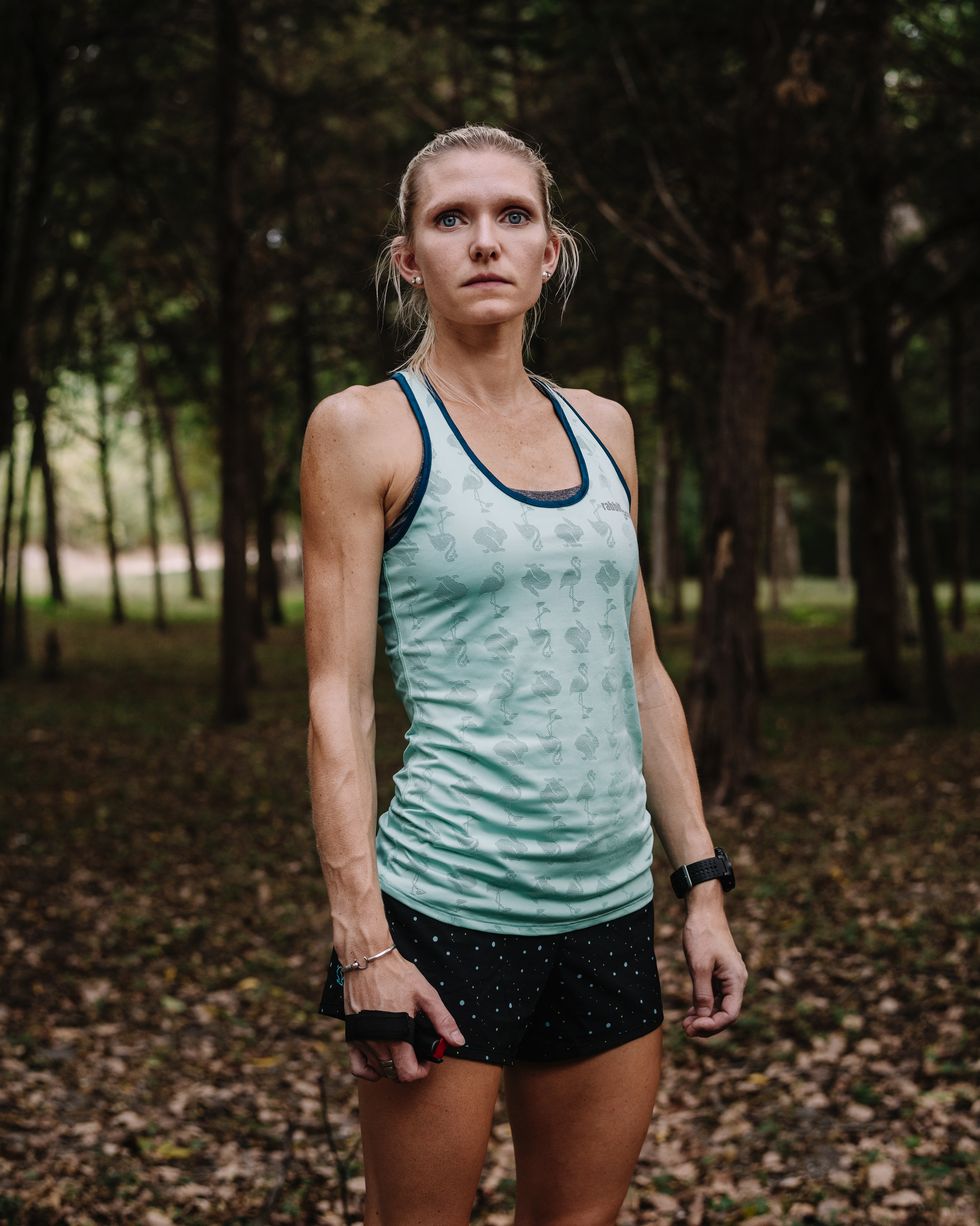

On the last Saturday of June 2019, Bryanna Gondeiro-Petrie left her in-laws’ house in eastern Washington state around 5:30 a.m. and headed down a lightly trafficked road. She needed to get out earlier than normal to squeeze in a quick shakeout run before traveling to Montana, where she would run the Missoula Marathon the next day.

As she ran against traffic, she noticed a black Toyota speeding toward her. Abruptly, the car slowed down. Then the driver rolled down the passenger-side window. Gondeiro-Petrie vividly recalls his “evil grin, as if he hit the jackpot in finding me,” she says.

The road behind Gondeiro-Petrie was empty—no houses, no cars, no side roads, and nowhere to go. A quarter mile ahead, she saw an older gentleman watering his trees, roughly 100 meters down a long driveway. She thought, “I need to get to that driveway.”

Gondeiro-Petrie sprinted. As she passed the car, the driver opened the passenger side door and yelled something unintelligible and laughed. He then hit the gas, flipped a U-turn, and intentionally drove down the wrong side of the road, coming up fast behind Gondeiro-Petrie. As the car pulled beside her, she reached the driveway and bolted down its length, shaking as she ran. The driver parked on the side of the road and watched her. When she reached the man watering the trees, he finally sped off.

That incident was the latest in a string of increasingly disturbing interactions. But Gondeiro-Petrie hadn’t always felt unsafe while running. “I would hear stories all the time, but I had this attitude that it would never happen to me,” she says. Over the past few years, her attitude has changed. Gondeiro-Petrie describes another run where she had to weave through streets to shake a car that was following her, and she says she knows countless women who have been attacked or forced to jump fences to get away from a threatening man.

Her concern escalated further last year when she moved with her family to the Dallas–Fort Worth area, where human trafficking is a growing concern. “I started running the same 1.4-mile loop around my house,” she says, which makes long run days tedious at best. During marathon training cycles, she’s logged up to 12 miles circling her home.

After the incident in Washington state, her relationship to running changed even more. She stopped trail running. She became more aware of her surroundings, watching passing men and cars with a hawk’s eye. She frequently changes up her routes, sometimes even midrun if something feels “off.” She carries pepper spray. She hatches just-in-case escape plans.

“I never imagined I would live at a time when I wouldn’t feel safe running by myself,” says Gondeiro-Petrie. “There are days when I feel like I can’t even enjoy myself because I’m on edge.”

There’s a complex calculation that takes place in women’s minds before lacing up for a run. In addition to what’s on the training plan, women often consider the time of day, their route, their clothes, whether to track their workout on Strava, whether to wear headphones, and what protection to carry—Mace, Taser, or an alarm. For many women, running doesn’t resemble the blissed-out, endorphin-filled escape it should be. Instead, we’re on guard, bracing ourselves against a constant threat of harassment. It’s a task more exhausting and mentally taxing than mile repeats.

And it’s far too prevalent: In a recent Runner’s World survey, a massive 84 percent of women said they have experienced some kind of harassment while running that left them feeling unsafe. That includes physical actions like groping, or being followed or flashed, as well as subtler forms like catcalls, honks, and lewd comments.

At best, harassment is distracting and annoying. At worst, it’s terrifying and detrimental to our health, negating all the physical, emotional, and mental benefits we get from running. And while the #MeToo movement has brought more attention to issues around sexual harassment and assault, there’s still work to do, especially when it comes to the unwanted attention that women face in public spaces, which includes the places we run, says Holly Kearl, founder of the nonprofit Stop Street Harassment. According to the organization’s 2019 study in conjunction with the University of California, San Diego Center on Gender Equity and Health, 68 percent of women reported being harassed in public spaces like streets, trails, and parks.

The fear women feel is real—and profound. In our survey, 67 percent of women said they were at least sometimes concerned they would be physically assaulted while running. A full 16 percent said that they have felt threatened enough while running that they feared for their lives. That sentiment is not unfounded. Stories of women who have been killed while running—like Mollie Tibbetts, Vanessa Marcotte, Karina Vetrano, Alexandra Brueger, Wendy Karina Martinez—have spread on social media, stoking fear and anxiety among women runners.

This heightened level of anxiety exacts a mental toll that can wedge its way into our nonrunning hours. “People minimize street harassment because they don’t see it as sexual harassment [since] it’s not rape or battery,” says Joan Cook, Ph.D., associate professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. But it acts like “toxic fumes that seep into the psyche,” she says. According to the Stop Street Harassment study, of those who experienced harassment or assault, 30 percent of women reported anxiety or depression and 23 percent said they changed their regular routine. And those women may even exhibit signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, Kearl says, heightening feelings of vulnerability, affecting sleep, and making it harder to focus at work, home, or school.

Natalie Mitchell, 46, was running easy along a beach bike path in Santa Monica, California, one Saturday morning in the spring of 2019. As she overtook a male runner, he started screaming profanities at her. He sprinted past Mitchell while continuing to gesture wildly in her direction. “He was pissed I passed him,” she says. Mitchell was scared. “If this guy tried to attack me, I had nothing to protect myself,” she says. “You hear about a normal woman who goes for a run and doesn’t come back. I have three kids to think about. I can’t risk that.” She didn’t say anything and finished her run while keeping a wide berth behind him.

Mitchell’s reaction is understandable—and common. When women encounter harassment, they often stay silent, both as a protective measure and because they’re not sure what else to do. “Women aren’t socialized to speak up and fight back,” says Kearl. And many women are afraid that if they engage with a harasser or fight back, the situation might escalate.

There is one forum where women are starting to feel safe talking about harassment: the internet. Social media has become an avenue for women to reclaim their experiences and nudge the conversation forward. While it’s not entirely free from trolling (there’s no shortage of comments like “Suck it up, buttercup,” “It’s a compliment!” and worse), women who post about their experiences with harassment are often met with a chorus of similar stories from other women, as well as support from men.

When a cyclist catcalled pro distance runner Emma Bates, 27, during her run, she was frustrated that she didn’t have the nerve to say something in the moment. So Bates took to Twitter.

“To the biker who referred to me as a ‘hottie’ on my run, u ruined my entire day,” she wrote. “Not because of what u said but because I didn’t have the courage to speak up for myself and tell u how completely unacceptable it was.” Nearly 2,000 people liked her original post, and hundreds shared their own stories of harassment on the run. “I do feel more empowered to speak out. There seems to be solidarity and more space to talk about this,” Bates says.

This social media solidarity is encouraging. But it’s not enough. Women deserve a safe and supportive environment in real life, too. Right now, the standard advice for women who run is to armor up—carry Mace or a Taser—or to run exclusively with a group or a dog. But those recommendations don’t guarantee safety, and they put the onus on women to protect ourselves from dangers we shouldn’t have to worry about in the first place. They limit the places and ways in which we can run.

We think there’s a better way. A way to stand up to harassment while also giving women and communities tools and strategies to actually feel safer. That’s why Runner’s World has created the Runners Alliance, a powerful initiative that offers concrete, real-time solutions to reduce harassment and improve the safety of the places we run.

It’s an initiative designed to bring together everyone who is fired up for change. Join us—together we can reclaim the right to run without fear.

The Runners Alliance is an initiative to help make running safer for women. Read more tips, strategies, and personal stories here.

Christine Yu is an award-winning journalist and author of the book Up to Speed: The Groundbreaking Science of Women Athletes. Her work focuses on the intersection of sports science and women athletes. She's a lifelong athlete who loves running, yoga, surfing, and skiing.