.

The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving

Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020:

Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque

JUNE 2, 2020 | BY DR. IHSAN BAGBY

SUMMARY

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. Reports featuring the results will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

.

Introduction

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The US Mosque Survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. This report will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

All of the US Mosque Surveys (2000, 2010, and 2020) were conducted in collaboration with a larger study of American congregations called Faith Communities Today (FACT), which is a project of the Cooperative Congregational Studies Partnership (CCSP), a multi-faith coalition of numerous denominations and faith groups, headquartered at Hartford Seminary. The strategy of FACT is to develop a common questionnaire and then have the member faith groups use that questionnaire to conduct a survey of their respective congregations. The US Mosque Surveys took the FACT common questionnaire and modified it to fit the mosque context.

The primary sponsors of the US Mosque Survey 2020 include many organizations: Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), Center on Muslim Philanthropy, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), and the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB). Other important supporters include Intuitive Solutions, International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), Islamic Circle of North America’s Council for Social Justice, Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and Hartford Institute for Religion Research (Hartford Seminary).

The lead researcher for the Mosque Survey is Dr. Ihsan Bagby. The Research Committee for the Mosque Survey includes:

-

- Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Kentucky

- Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU

- Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center

- Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Religion, Hartford Seminary

- Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University

- Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Research and Data Center

- Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Justice

Research Methodology

The first phase of the Mosque Survey was a count of all mosques, which was conducted from June to November 2019. Starting from the 2010 mosque database, an initial internet search was conducted to verify mosques, identify new mosques, and eliminate mosques that no longer exist. This internet search depended primarily on the excellent databases found on the websites of Muslim Guide and Salatomatic. Mosques were verified via the mosques’ websites, Google Maps, and a phone call. The internet search resulted in an initial count of 2948. After the internet search, a first-class (address correction) letter and a short questionnaire were sent to all the mosques. Various options for completing the questionnaire were offered, including an online version. Of the 2948 mailings, 164 responses were received—a 5.5% response rate. This low response rate is the rationale for not depending on an online version for the comprehensive survey. Returned mail was checked with Google Maps and a general internet search. The final result was a count of 2769 mosques.

The second phase was the comprehensive survey conducted via telephone interview of a mosque leader using a long questionnaire. The comprehensive survey entailed a random sampling from the list of 2769 mosques. To achieve the goal of a margin of error of +/- 5%, 337 questionnaires had to be completed. The sample of mosques was stratified by state, such that each state had a set number of mosques for which the questionnaire had to be completed. The Mosque Survey randomly sampled 700 mosques, and 470 questionnaires were completed, fulfilling the target for each state. The work of completing the questionnaires started in November 2019 and ended in October 2020. The COVID-19 crisis made the task of finding a mosque leader more difficult; thus, completion of the survey was delayed.

The results of the US Mosque Survey are all pre-COVID. Thus, interviewers asked the mosque leaders about the situation of their mosques before the outbreak of COVID-19.

For the Mosque Survey, mosques were defined as a Sunni or Shi’ite Muslim organization that organizes Jum’ah prayer, conducts other Islamic activities, and controls the space in which activities are held.* This definition would include “musallas” which have an organization that does more than just conduct Jum’ah prayers. This definition excludes those places where only Jum’ah prayer is held, like a hospital or airport. Some Shi’ite religious organizations do not hold Jum’ah prayer due the absence of a resident scholar or because they consider themselves an Imambargah or Hussainiya. These Shi’ite organizations were classified as mosques. The Mosque Survey did not include organizations outside of the Sunni and Shi’ite American Muslim community like the Nation of Islam, Moorish Science Temple, Ismailis, and Ahmadiyyah.*

*This portion of the methodology was lightly updated for clarity on June 29, 2021.

Thanks go to the numerous interviewers who were hired to conduct the mosque count and interview mosque leaders. Special thanks to Intuitive Solutions under Tayyab Yunus who supplied several excellent interviewers. Thanks also to the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California for assisting the Mosque Survey in identifying mosque leaders and supplying interviewers.

The results of the US Mosque Survey 2020 are divided into two reports. Report 1 focuses on essential statistics, mosque participants, mosque administration, and the basic characteristics of Shi’ite mosques. Report 2 focuses on Islamic approaches in understanding Islam, perspectives of mosque leaders on American society, mosque activities, women in the mosque, and the perspectives and activities of Shi’ite mosques.

The results recorded in the two reports include both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques. A separate section on Shi’ite mosques is included in both reports.

Note: Percentages throughout this report may not total 100% due to rounding.

INTRODUCTION

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The US Mosque Survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. This report will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

DOWNLOADS

Introduction

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The US Mosque Survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. This report will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

All of the US Mosque Surveys (2000, 2010, and 2020) were conducted in collaboration with a larger study of American congregations called Faith Communities Today (FACT), which is a project of the Cooperative Congregational Studies Partnership (CCSP), a multi-faith coalition of numerous denominations and faith groups, headquartered at Hartford Seminary. The strategy of FACT is to develop a common questionnaire and then have the member faith groups use that questionnaire to conduct a survey of their respective congregations. The US Mosque Surveys took the FACT common questionnaire and modified it to fit the mosque context.

The primary sponsors of the US Mosque Survey 2020 include many organizations: Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), Center on Muslim Philanthropy, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), and the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB). Other important supporters include Intuitive Solutions, International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), Islamic Circle of North America’s Council for Social Justice, Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and Hartford Institute for Religion Research (Hartford Seminary).

The lead researcher for the Mosque Survey is Dr. Ihsan Bagby. The Research Committee for the Mosque Survey includes:

-

- Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Kentucky

- Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU

- Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center

- Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Religion, Hartford Seminary

- Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University

- Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Research and Data Center

- Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Justice

Research Methodology

The first phase of the Mosque Survey was a count of all mosques, which was conducted from June to November 2019. Starting from the 2010 mosque database, an initial internet search was conducted to verify mosques, identify new mosques, and eliminate mosques that no longer exist. This internet search depended primarily on the excellent databases found on the websites of Muslim Guide and Salatomatic. Mosques were verified via the mosques’ websites, Google Maps, and a phone call. The internet search resulted in an initial count of 2948. After the internet search, a first-class (address correction) letter and a short questionnaire were sent to all the mosques. Various options for completing the questionnaire were offered, including an online version. Of the 2948 mailings, 164 responses were received—a 5.5% response rate. This low response rate is the rationale for not depending on an online version for the comprehensive survey. Returned mail was checked with Google Maps and a general internet search. The final result was a count of 2769 mosques.

The second phase was the comprehensive survey conducted via telephone interview of a mosque leader using a long questionnaire. The comprehensive survey entailed a random sampling from the list of 2769 mosques. To achieve the goal of a margin of error of +/- 5%, 337 questionnaires had to be completed. The sample of mosques was stratified by state, such that each state had a set number of mosques for which the questionnaire had to be completed. The Mosque Survey randomly sampled 700 mosques, and 470 questionnaires were completed, fulfilling the target for each state. The work of completing the questionnaires started in November 2019 and ended in October 2020. The COVID-19 crisis made the task of finding a mosque leader more difficult; thus, completion of the survey was delayed.

The results of the US Mosque Survey are all pre-COVID. Thus, interviewers asked the mosque leaders about the situation of their mosques before the outbreak of COVID-19.

For the Mosque Survey, mosques were defined as a Sunni or Shi’ite Muslim organization that organizes Jum’ah prayer, conducts other Islamic activities, and controls the space in which activities are held.* This definition would include “musallas” which have an organization that does more than just conduct Jum’ah prayers. This definition excludes those places where only Jum’ah prayer is held, like a hospital or airport. Some Shi’ite religious organizations do not hold Jum’ah prayer due the absence of a resident scholar or because they consider themselves an Imambargah or Hussainiya. These Shi’ite organizations were classified as mosques. The Mosque Survey did not include organizations outside of the Sunni and Shi’ite American Muslim community like the Nation of Islam, Moorish Science Temple, Ismailis, and Ahmadiyyah.*

*This portion of the methodology was lightly updated for clarity on June 29, 2021.

Thanks go to the numerous interviewers who were hired to conduct the mosque count and interview mosque leaders. Special thanks to Intuitive Solutions under Tayyab Yunus who supplied several excellent interviewers. Thanks also to the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California for assisting the Mosque Survey in identifying mosque leaders and supplying interviewers.

The results of the US Mosque Survey 2020 are divided into two reports. Report 1 focuses on essential statistics, mosque participants, mosque administration, and the basic characteristics of Shi’ite mosques. Report 2 focuses on Islamic approaches in understanding Islam, perspectives of mosque leaders on American society, mosque activities, women in the mosque, and the perspectives and activities of Shi’ite mosques.

The results recorded in the two reports include both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques. A separate section on Shi’ite mosques is included in both reports.

Note: Percentages throughout this report may not total 100% due to rounding.

.

Major Findings

The Number of Mosques Continues to Grow

-

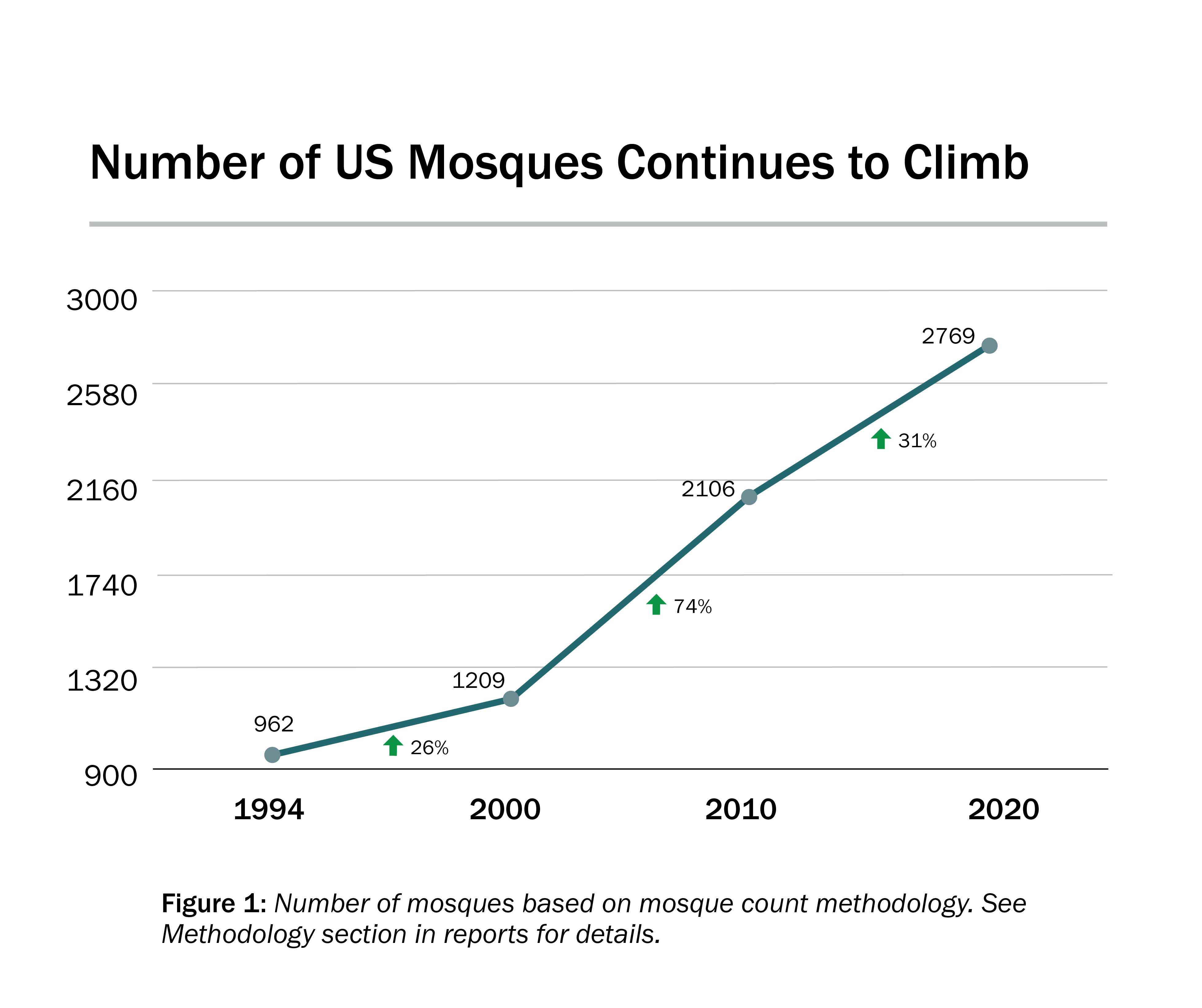

- In 2020, the US Mosque Survey counted 2769 mosques, which is a 31% increase from the 2010 count of 2106 mosques. Undoubtedly, the primary driving force for the increase of mosques is the steady expansion of the population of Muslims in America due to immigration and birth rate.

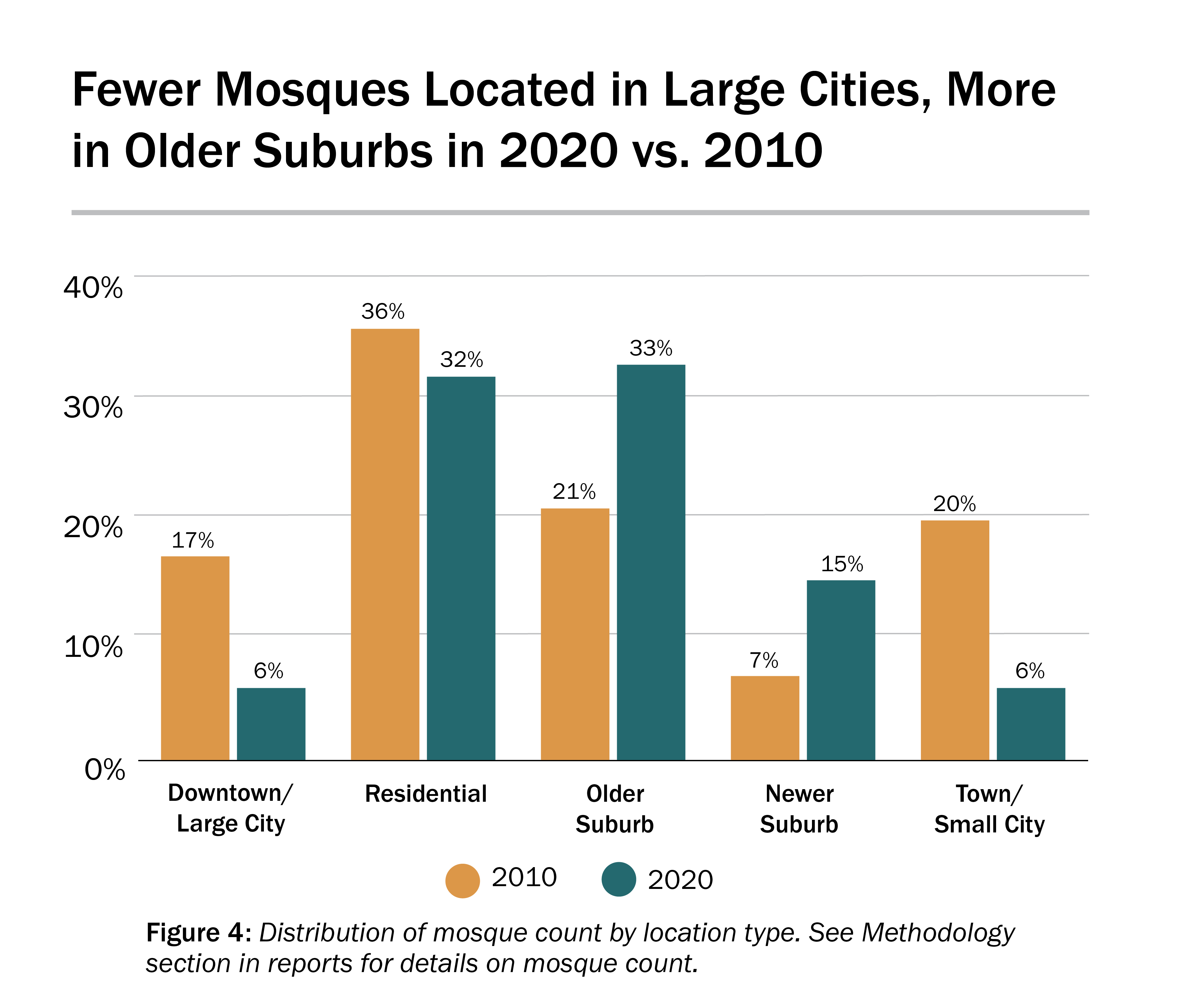

- Mosques are becoming more suburban as major declines occurred in the number of mosques located in towns/small cities and in downtown areas of large cities. Mosques in towns/small cities decreased from 20% in 2010 to 6% in 2020. The apparent cause is the dwindling population of Muslims in these towns/small cities due to the drying up of jobs in these areas and the moves of young adults, children of mosque founders, and activists to large cities for education and jobs. In 2010, 17% of mosques were found in downtown areas, but in 2020 that figure is down to 6%. This decrease is most probably tied to the decrease of African American mosques and the general move of mosques to suburban locations.

Did You Know?

Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque is the first of two reports that will comprise the complete US Mosque 2020 survey. Report 2 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Perspectives and Activities will be available in July 2021.

The Number of Mosque Participants Continues to Grow

-

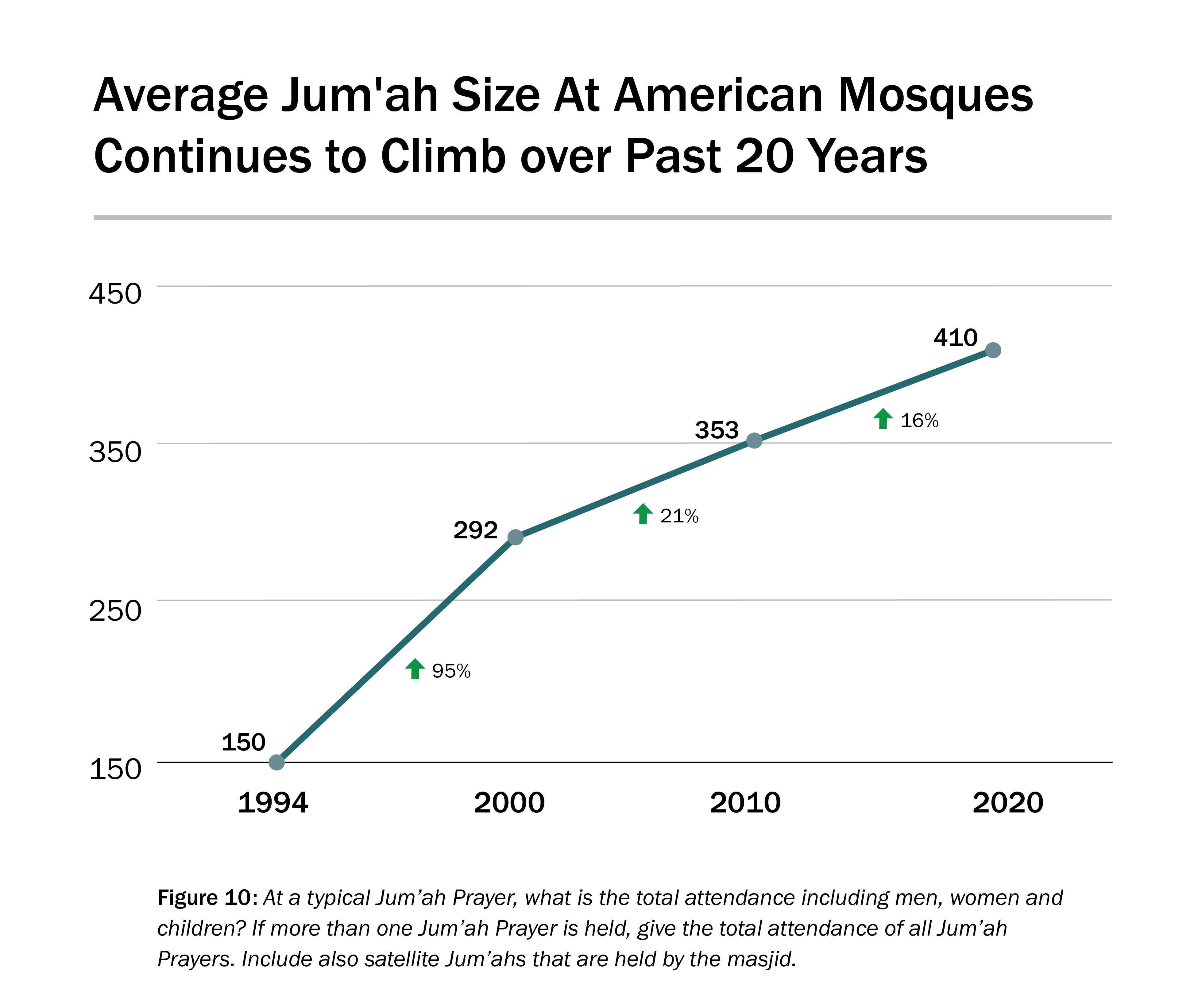

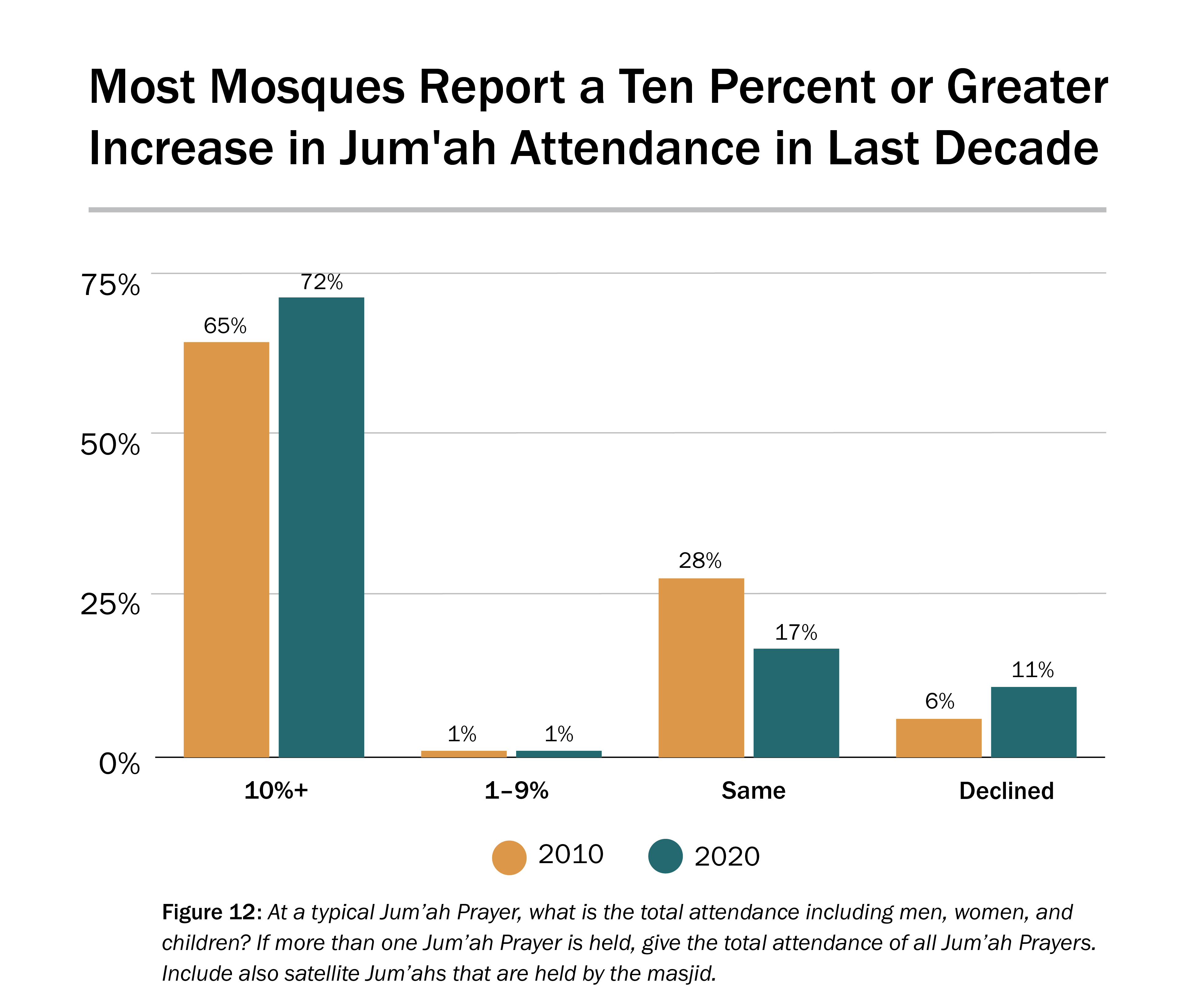

- Jum’ah prayer (the weekly Muslim congregational prayer held on Friday) averaged 410 attendees in 2020, as compared to 353 in 2010, which equals a 16% increase. Almost three-fourths (72%) of mosques recorded a 10% or more increase in Jum’ah attendance.

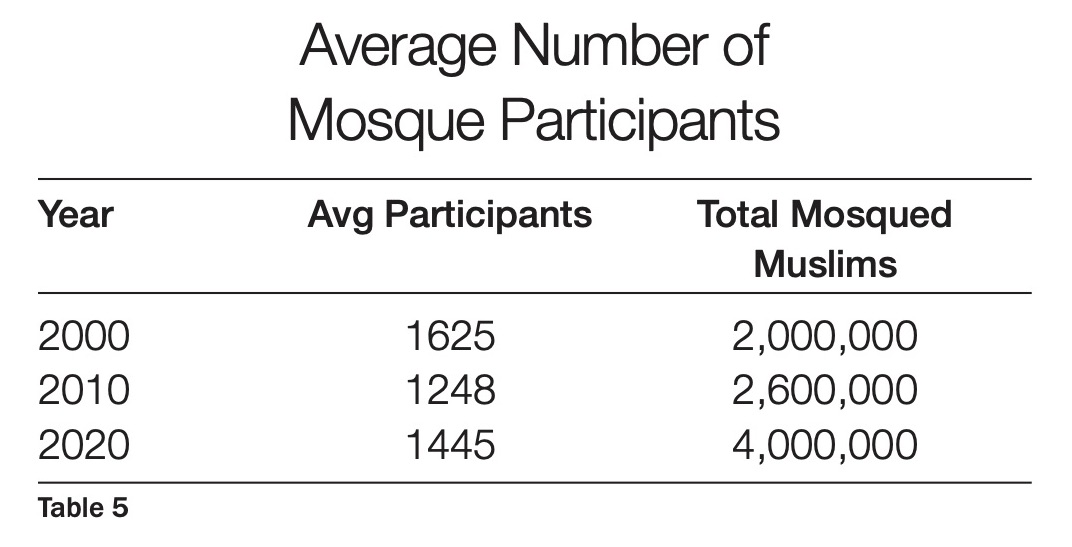

- The total number of mosque participants, which is measured by the number of Muslims who attend the high holiday Eid prayer after Ramadan, increased to 1445, which is a 16% increase from the 2010 count of 1248.

- Using the Eid prayer count, the number of “mosqued” Muslims is approximately 4 million.

Conversions Decreased

-

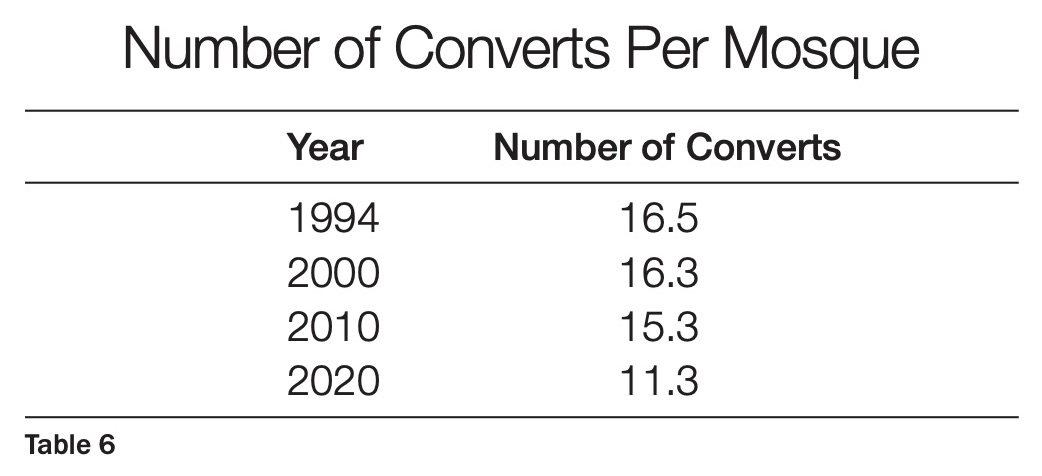

- The number of converts to Islam in mosques declined dramatically. From 15.3 converts per mosque in 2010, the average number of converts in 2020 is 11.3. The primary reason is the decline in African American converts, especially in African American mosques.

Sharp Decrease in African American Mosques and the Number of African American Attendees

-

- In 2020, African American mosques comprised 13% of all mosques, but in 2010 African American mosques accounted for 23% of all mosques—a 43% decrease (dominant ethnic groups within mosques are calculated as: any group over 55% of all mosque participants; 50%-59% of one group and all others less than 40%; 40-49% of one group and all others less than 30%; 35-39% of one group and all others less than 20%). This is especially noteworthy considering African American Muslims account for roughly 28% of all American Muslims according to ISPU.

- In 2020, African American Muslims comprised 16% of all attendees in mosques, but in 2010 that figure was 23%—a 33% decrease.

- More study is needed to understand this phenomena, but apparent causes are the decline of African American converts (which constitutes the life-blood of growth in African American mosques), the inability of mosques to attract and maintain African American young adults, and the overall aging of African American Muslims, many of whom converted in the 1960s and 1970s.

Young Adult Muslims—Good News and Bad News

-

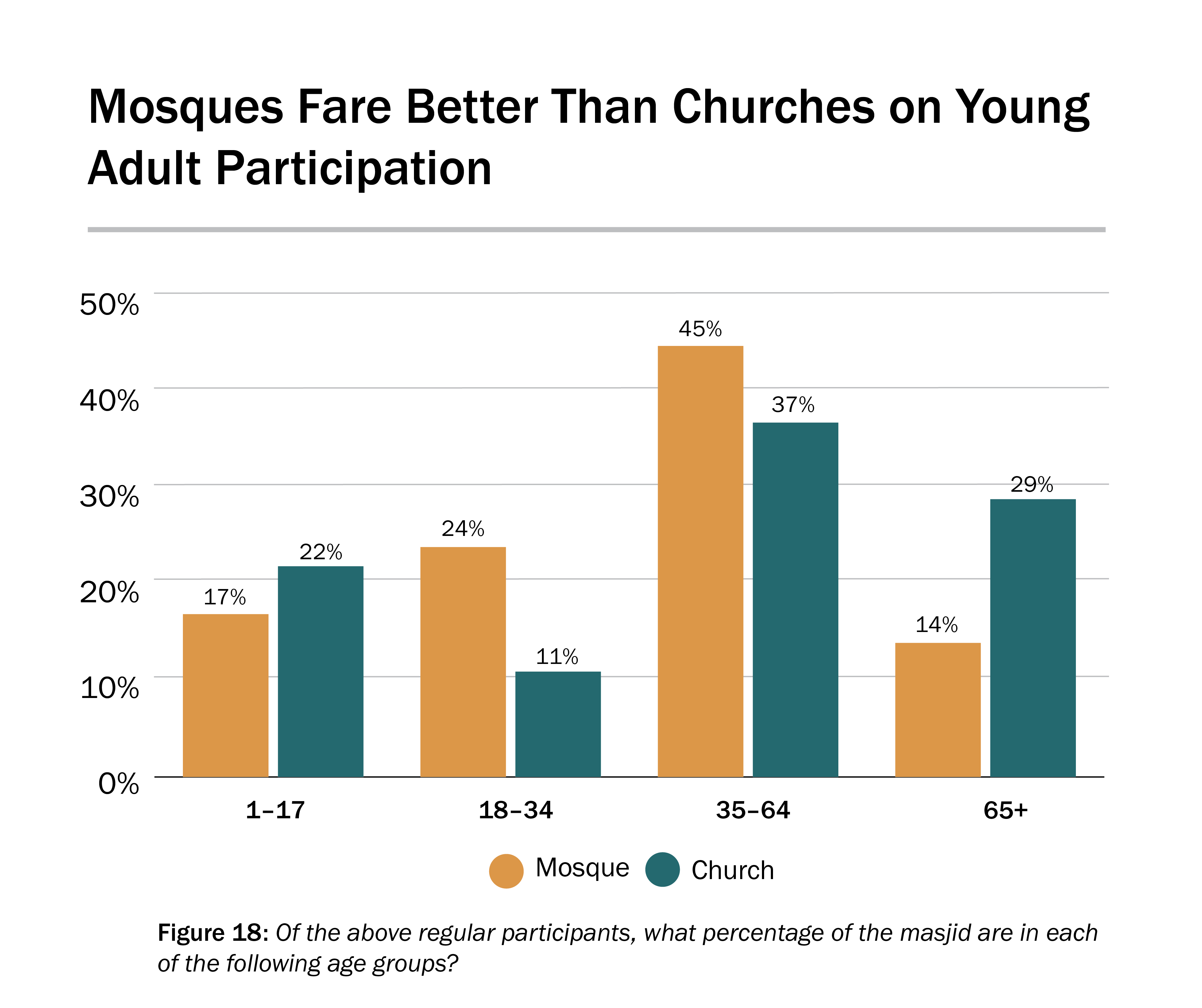

- Good news. Almost one-fourth (24%) of mosque participants are aged 18-34, roughly the ages of Generation Z and young Millennials. This is a very respectable percentage when compared to churches where about 11% of their attendees are 18-34.

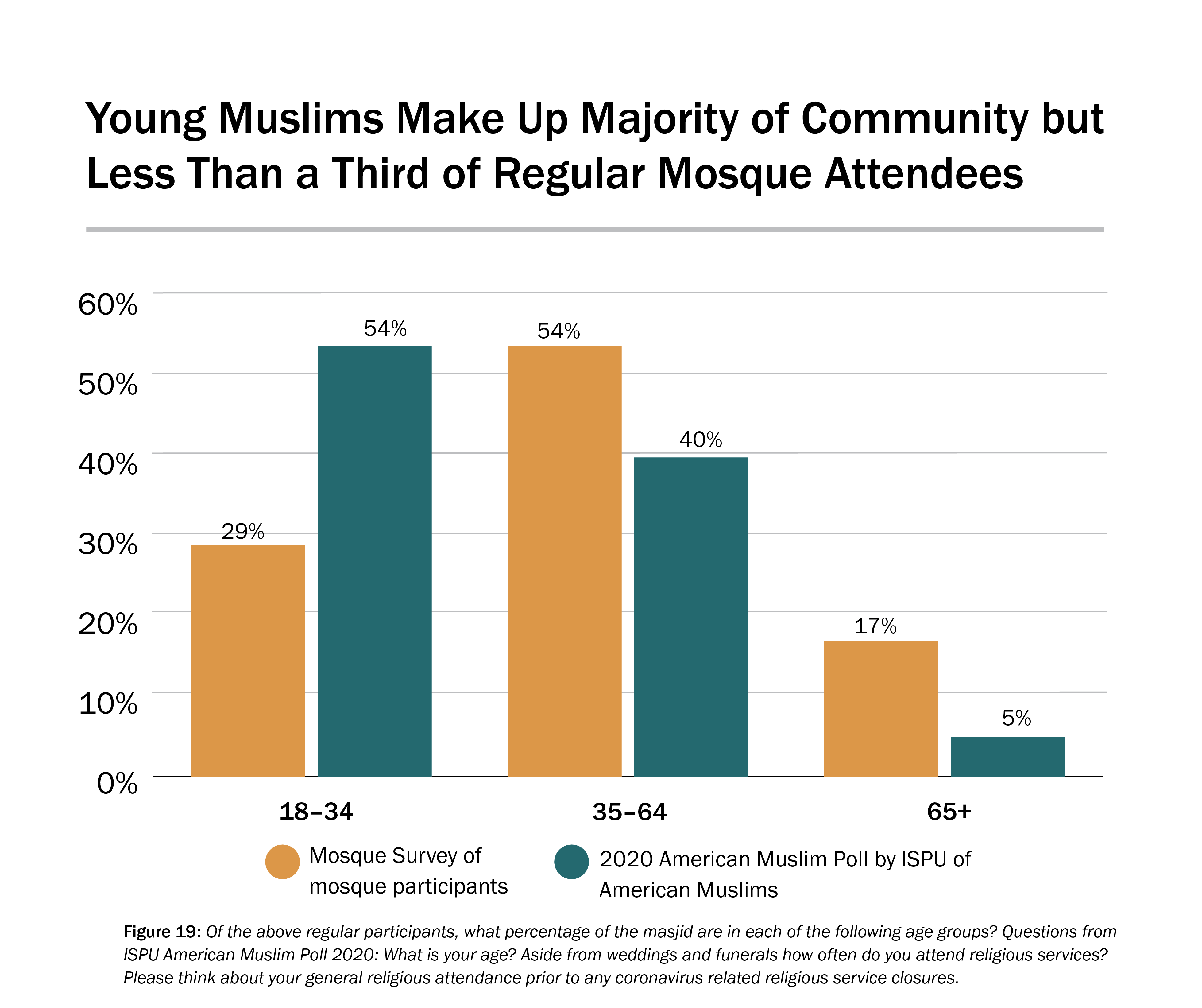

- Bad news. ISPU found that in 2020, 54% of adult Muslims are aged 18-34 (the American Muslim community is a very young community). Eliminating the children’s age group of 1-17, the US Mosque Survey 2020 estimates that 29% of adult mosque attendees are 18-34, which is far below ISPU’s data indicating 54% of the American Muslim population are young adult Muslims (ages 18-34). Based on this large difference, mosques are not attracting a significant percentage of Generation Z and young Millennials. Mosques have not lost the battle for the hearts and minds of young adult Muslims, but they have not won the battle either.

The Number of Purpose-Built Mosques Continues to Grow

-

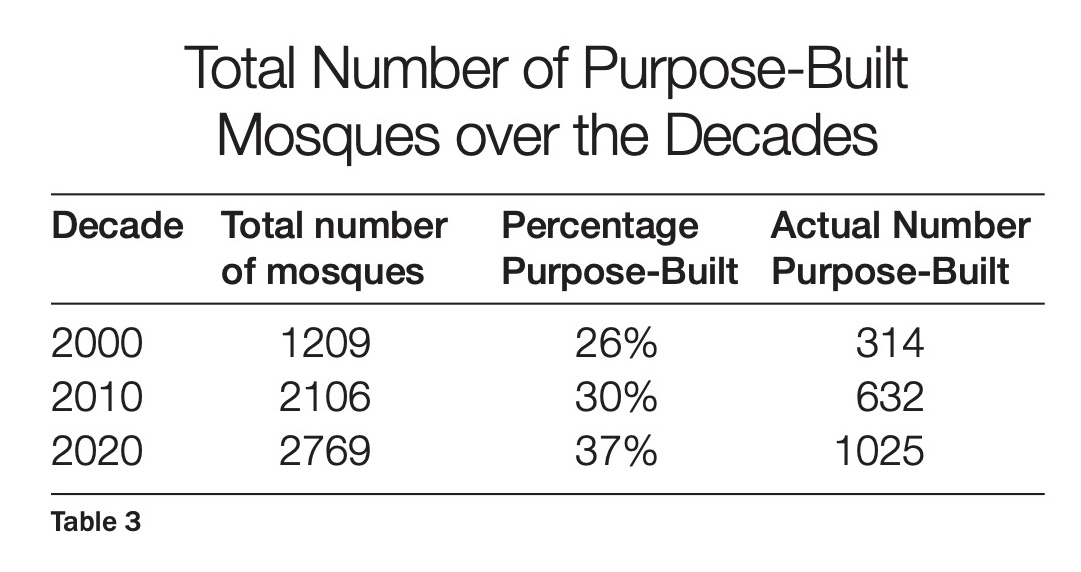

- In 2020, 37% of all mosques were built as a mosque. This is a substantial increase from 2010, when 30% of mosques were purpose-built. Taking into consideration actual numbers instead of percentages, 37% of all mosques in 2020 means that 1,025 mosques were purpose-built. In 2010, 30% of mosques equaled 632 purpose-built mosques. In 2000, only 314 mosques were purpose-built. The American Muslim community maintained its building spree for the past few decades.

Neighborhood and Zoning Board Resistance to Mosque Development Has Increased

-

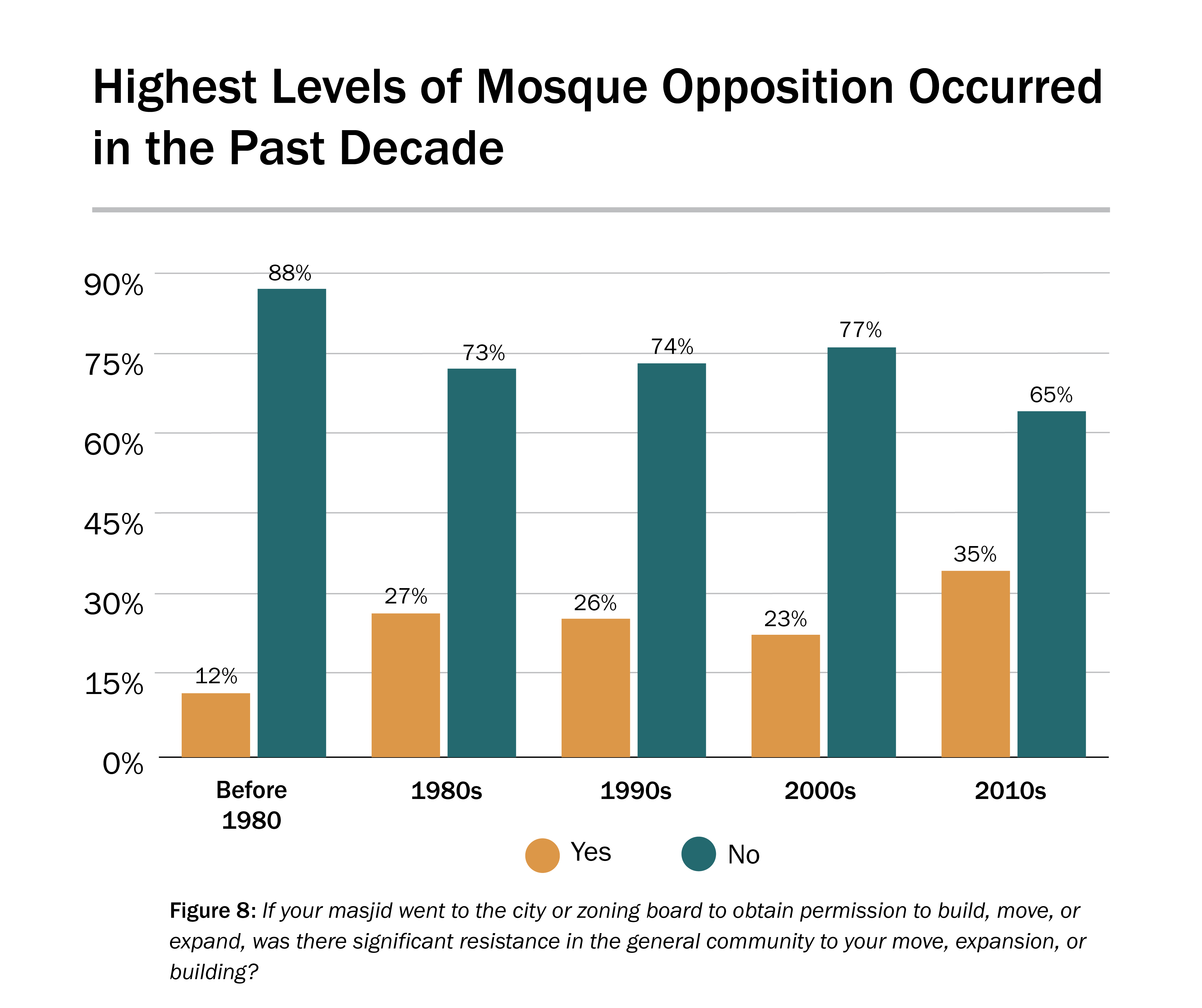

- In the past decade (2010-2019), 35% of mosques encountered significant resistance from their neighborhood or city when they tried to obtain permission to move, expand, or build. In comparison, from 1980-2009 the average percentage of mosques that met resistance was 25%. Apparently, negative attitudes toward Muslims grew in the last decade. Mosque opposition represents an institutional form of anti-Muslim discrimination. According to ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2020, more than any other group that experiences religious discrimination, Muslims do so on an institutional, not just interpersonal, level.

More Imams are Full-Time and Paid, and More are American-Born

-

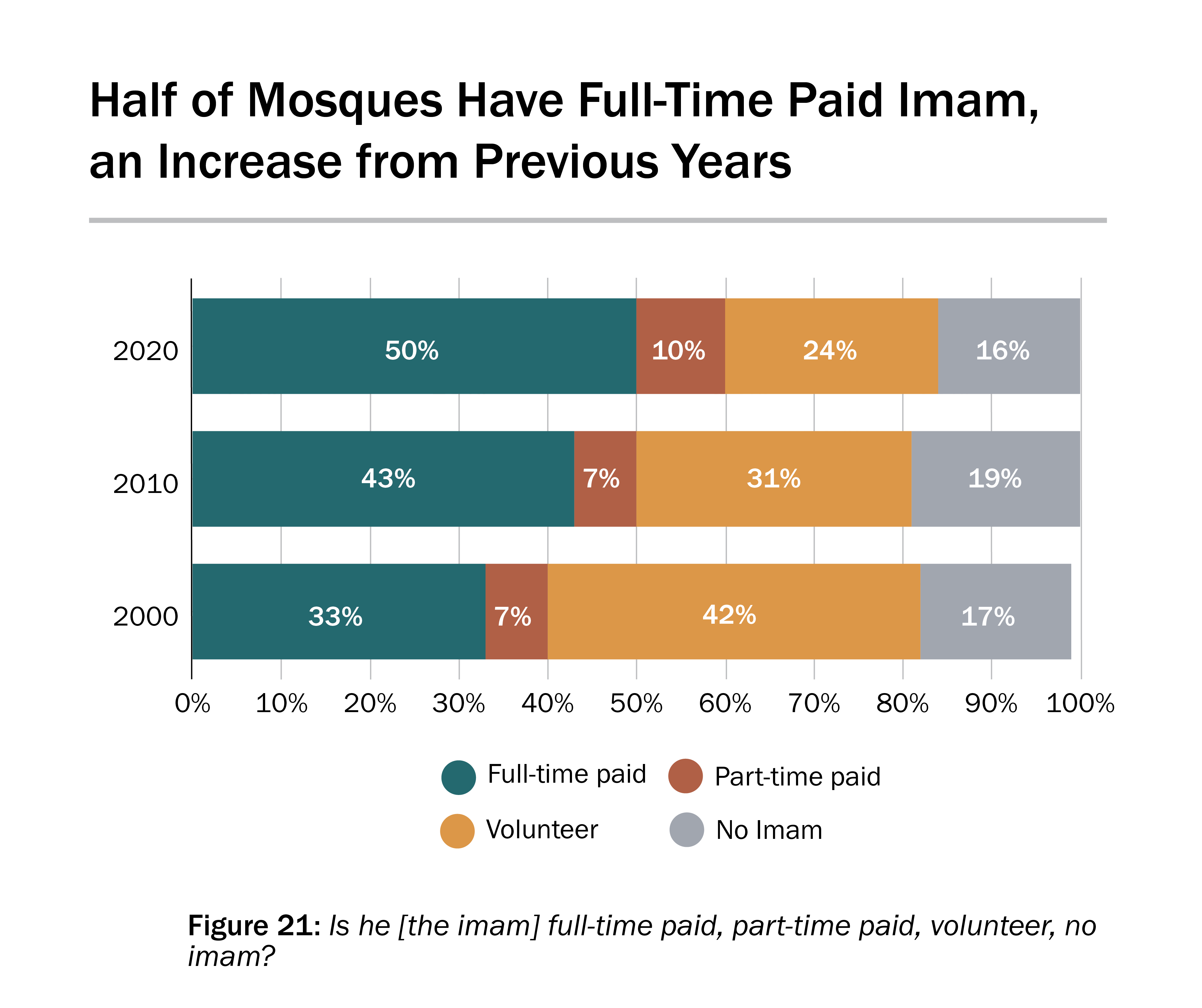

- Half of American mosques have a full-time paid imam as compared to 2010 when 43% of mosques had a full-time paid imam. This percentage is well short of churches and synagogues that have full-time paid religious leaders. Nevertheless, it shows steady progress.

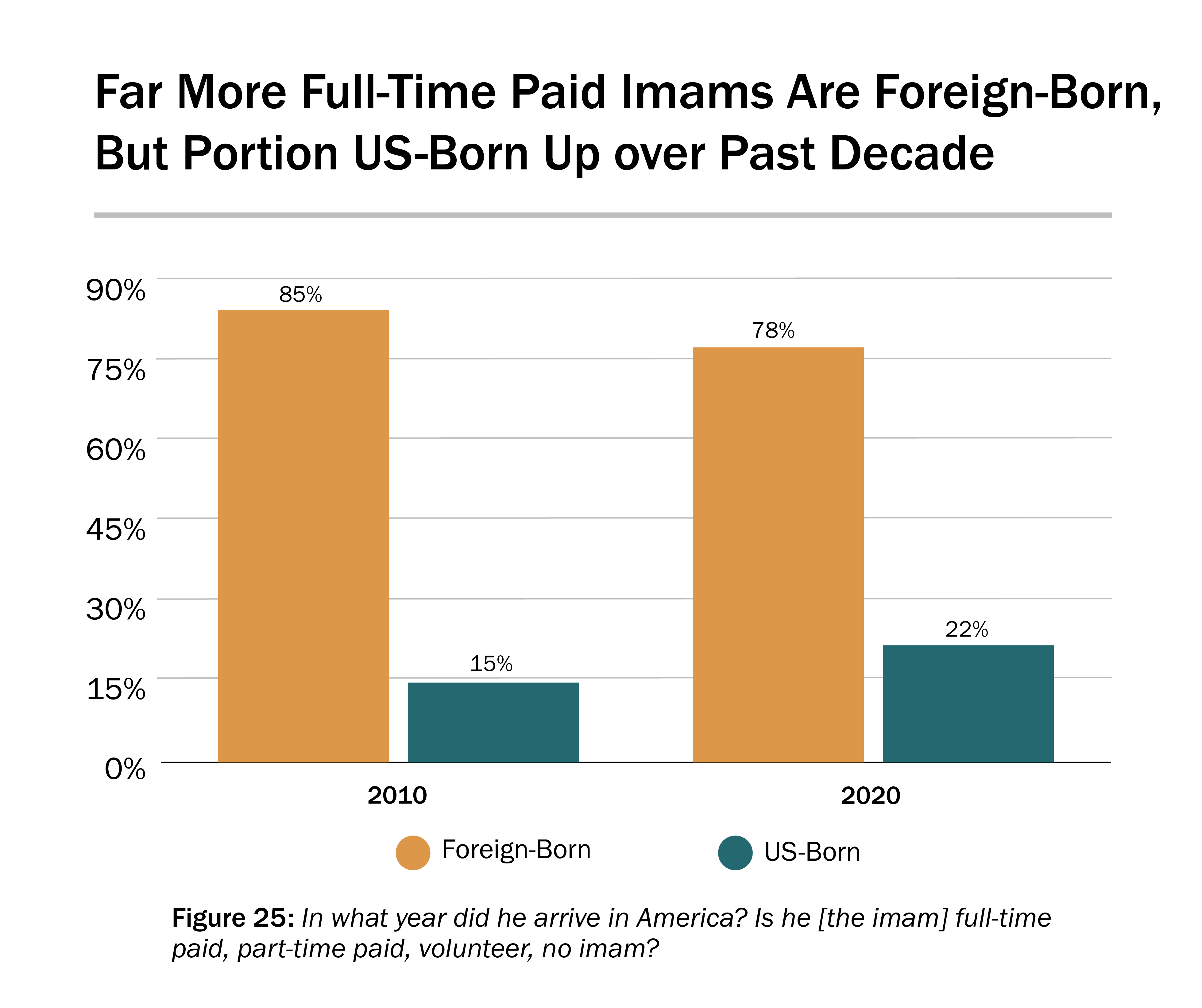

- Of full-time paid imams, 22% were born in America which is an increase from 15% in 2010. The inevitable evolution to the preference of hiring American-born imams is slowly manifesting.

- Only 6% of all imams received their Islamic degree (BA, MA, PhD) from an American institution, and no one seminary, university or institute is predominant in granting these degrees. The absence of a leading US-based Islamic seminary is an impediment for increasing the number of American-born imams.

Mosque Governance is Still Varied and Evolving

-

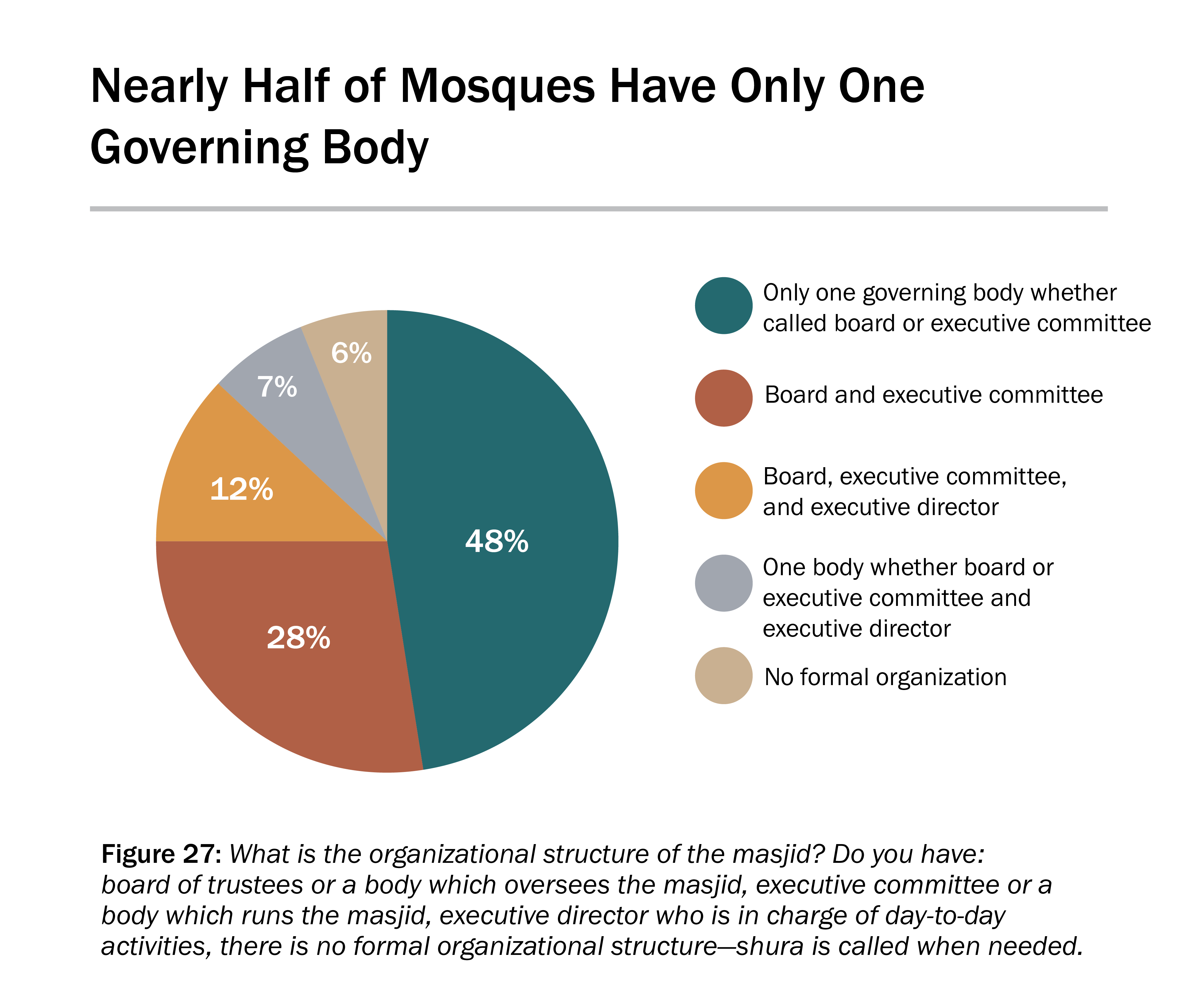

- No one governance model typifies mosques.

- Almost half (48%) of mosques have one volunteer governing body (usually called a board of directors or an executive committee), which manages the day-to-day activities of the mosque. In larger mosques with Jum’ah attendance over 500, the more common governing structure is to have two bodies: a board of trustees, which provides oversight, and an executive committee, which manages the mosque.

- Only a handful of very large mosques have paid staff to manage the mosque; therefore, the vast majority of mosques (76%) are managed entirely by volunteers.

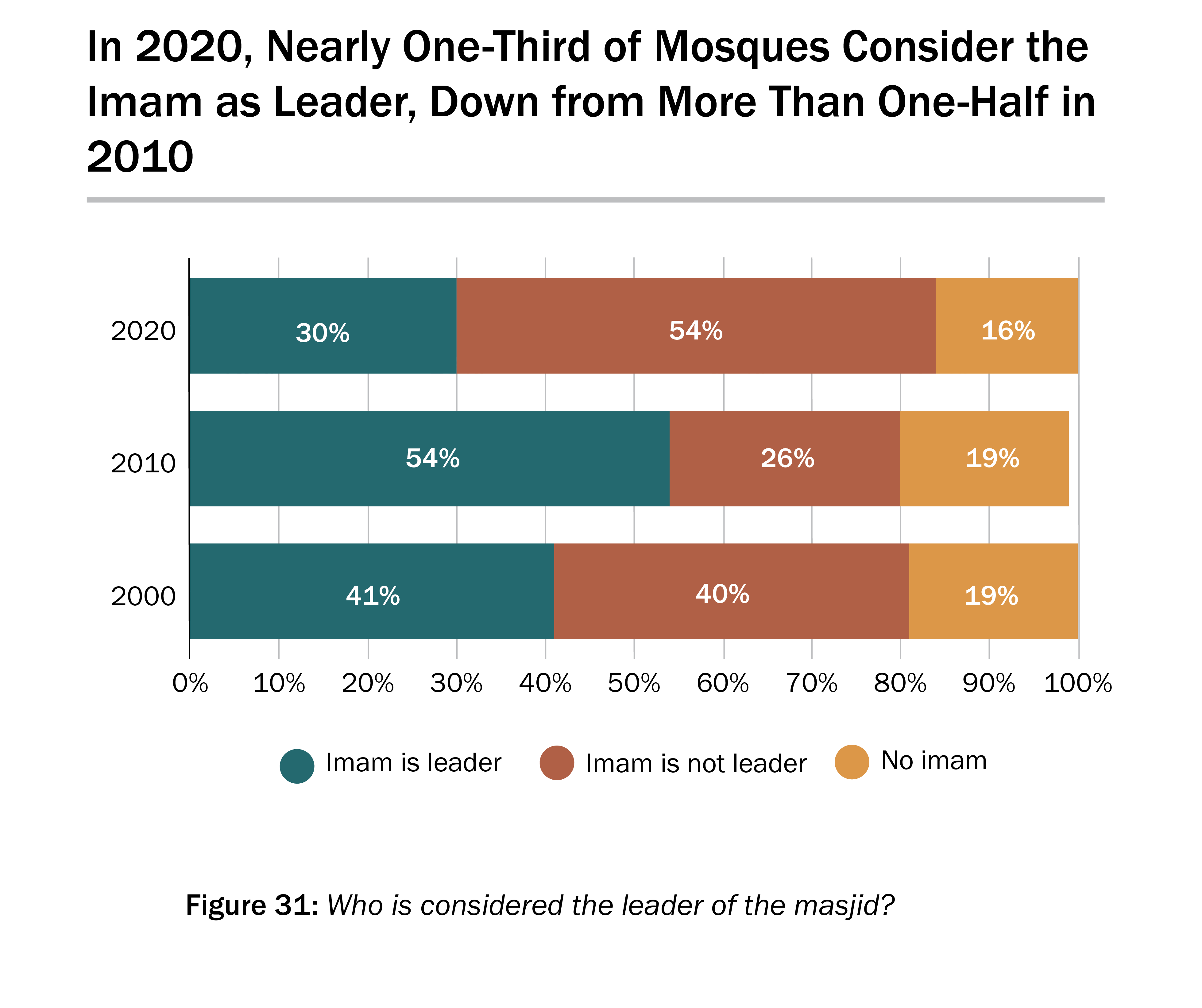

- The imam is considered the leader of the mosque in only 30% of all mosques. Lay leadership dominates most mosques.

- In 77% of mosques, imams have no managerial role. Over half of mosques (54%) have a shared governance arrangement between lay leadership and the imam, with the lay leadership taking charge of management and the imam taking responsibility for religious affairs. In 23% of mosques, the lay leadership runs all aspects of the mosque including religious affairs, and the imam leads the prayers. Only in a few instances (almost all African American mosques) does the imam have both religious and management responsibilities. Typically, in the shared governance model, mosque leadership and the final decision-making power lie with lay leadership and not the imam.

Mosque Income Continues to Grow

-

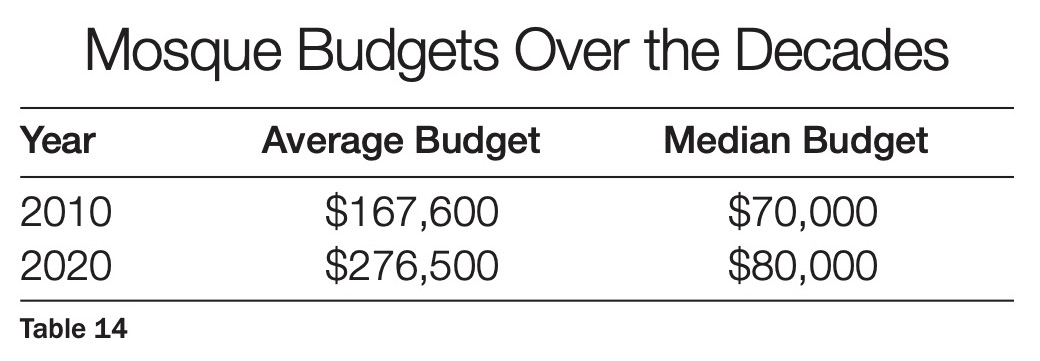

- The average mosque budget in 2020 was $276,500 and the median budget $80,000. This is a substantial increase from 2010’s average budget of $167,600 and the median budget of $70,000. (These figures do not include capital campaigns to build or expand mosques.)

- Mosques collect on average $40,640 for zakah (a required charity which is to be given to poor people).

- Combining budget and zakah, mosques collect on average $317,140.

- Mosque and church incomes are roughly the same, but churches achieve their income levels with far fewer people. Churches average $311,782 with 180 regular participants. Mosque income averages $317,140 with an average Jum’ah attendance of 410. Dividing income by participants, church participants give $1732 per year, and mosque participants give $674 per year.

US Mosque Survey 2020 Part One:

.

Basic Characteristics of Mosques

Mosque Essential Statistics

Number of Mosques

Number of US Mosques Continues to Climb

The total number of mosques continues to grow at a steady pace. The US Mosque Survey identified 2,769 mosques in 2020. This represents a 31% increase from the 2010 count of 2106. (See the methodology of the mosque count in the Introduction.)

The dominant factors behind the increased number of mosques have been the same in the last few decades:

-

- The overall American Muslim community continues to grow due mainly to the steady flow of new immigrants. New immigrants tend to be religious and attend mosques to find solace and stability in a trying period of transition to a new culture.

- When newer immigrant groups, such as Somalis, West Africans, Iraqis, Burmese, etc., reach a critical mass and/or achieve greater financial capabilities, they tend to establish their own mosques. This factor highlights the point that half of the American Muslim community is still largely a first-generation immigrant community with 51% of American Muslims born outside of the United States, according to ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2020.

- The expanding population of Muslims in suburbs and new areas of cities lead Muslims to start a mosque which is more conveniently located.

- Within mosques, diverse ethnicities and religious differences (conservative-moderate; Sunni-Shi’ite) lead groups to establish their own mosques which better reflect their customs or understanding of Islam.

Ultimately, population growth and the very diverse nature of the American Muslim community dictates the demographics of growth. Pew Research Center has established in their 2017 study that the American Muslim community continues to expand due largely to immigration and a higher fertility rate. Pew estimated that the Muslim population grew by 26% from 2010 to 2017 which corresponds nicely with the 31% increase in mosques from 2010 to 2020. (See Pew Research in Sources.)

Location of Mosques

States, Cities and Regions

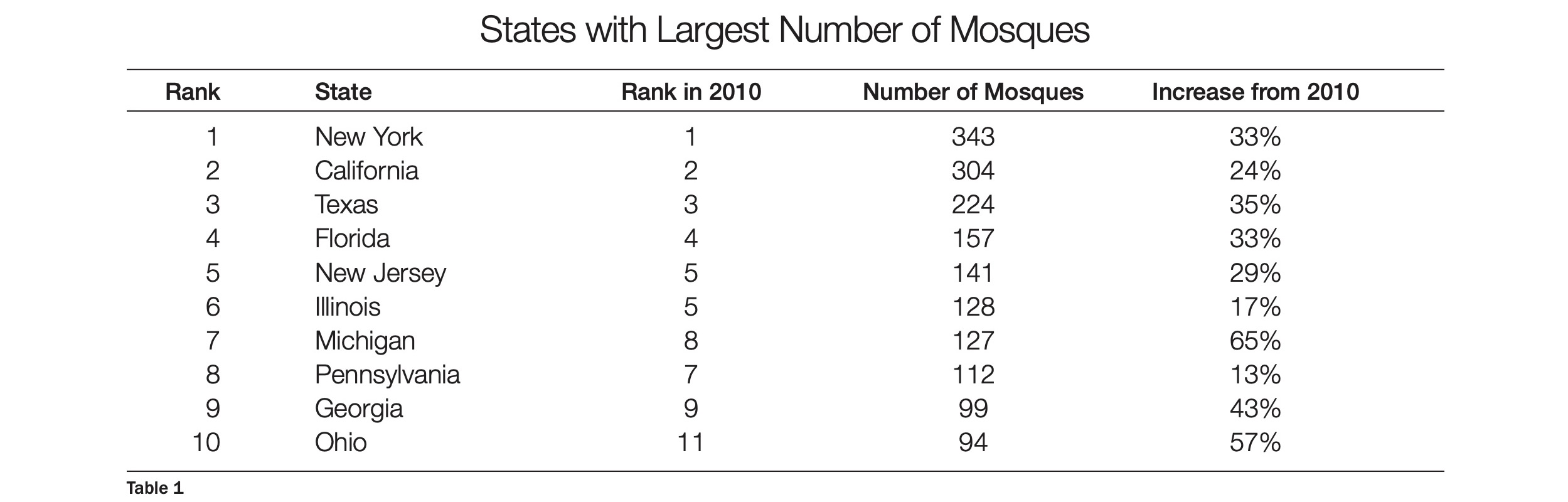

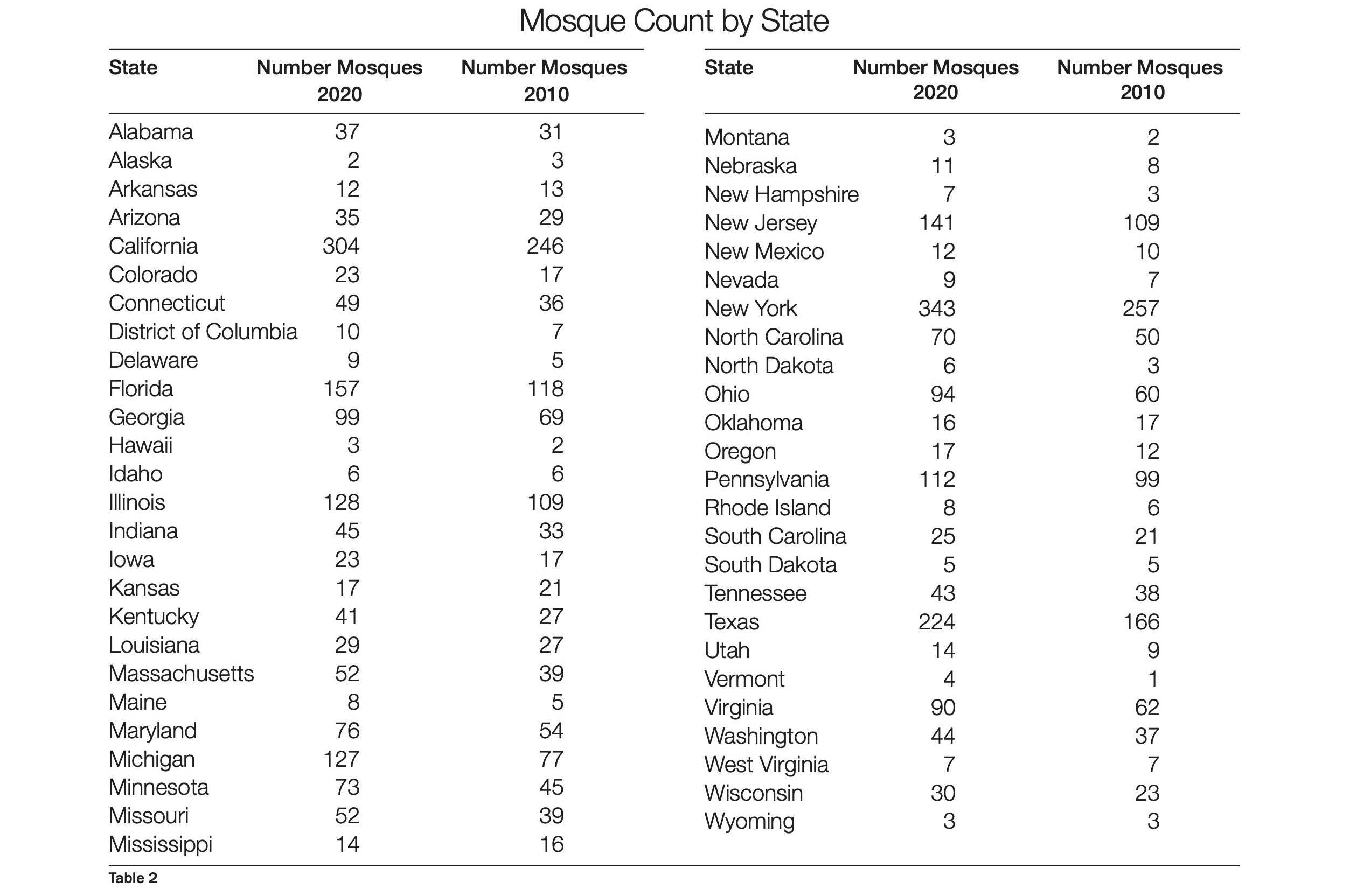

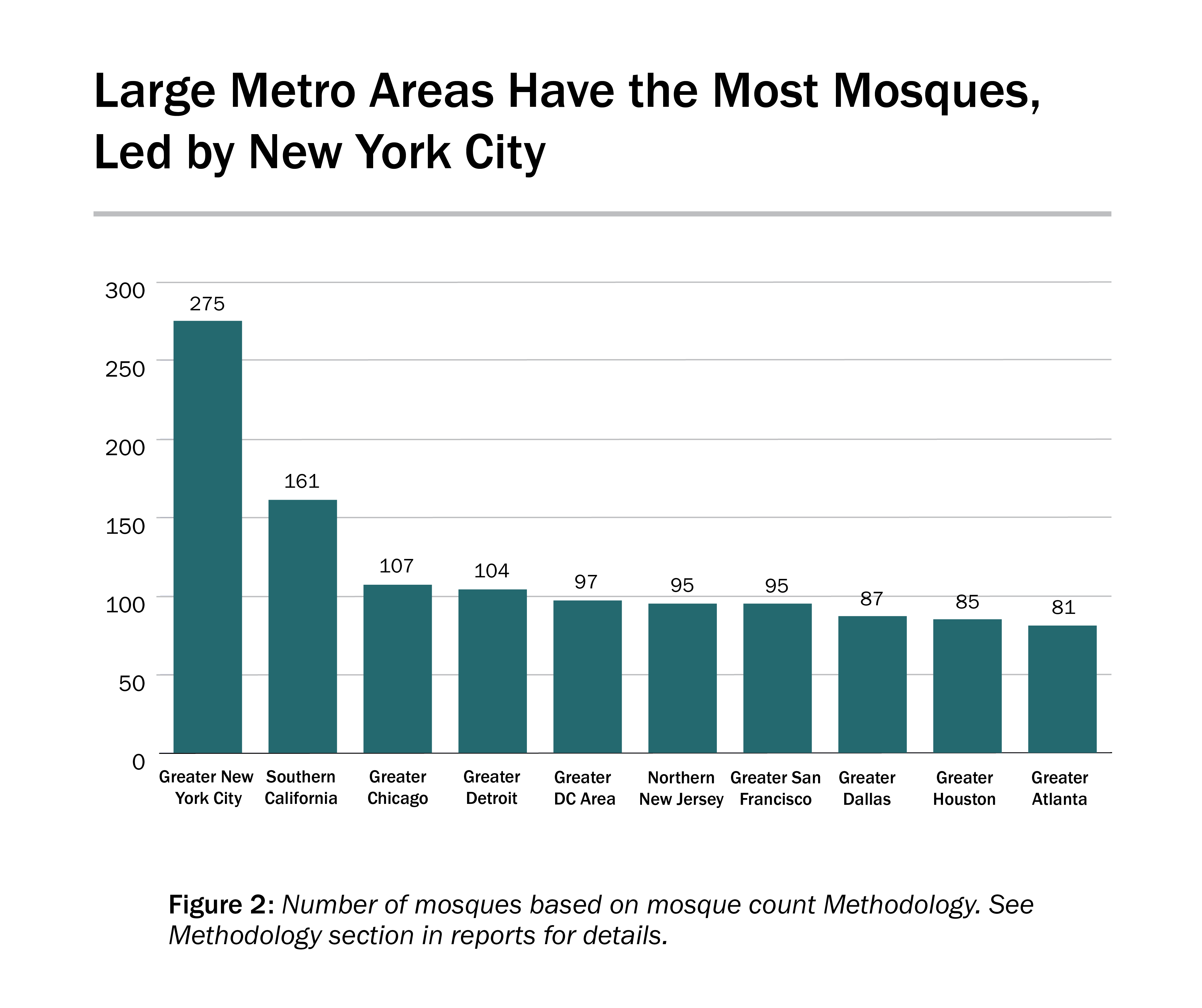

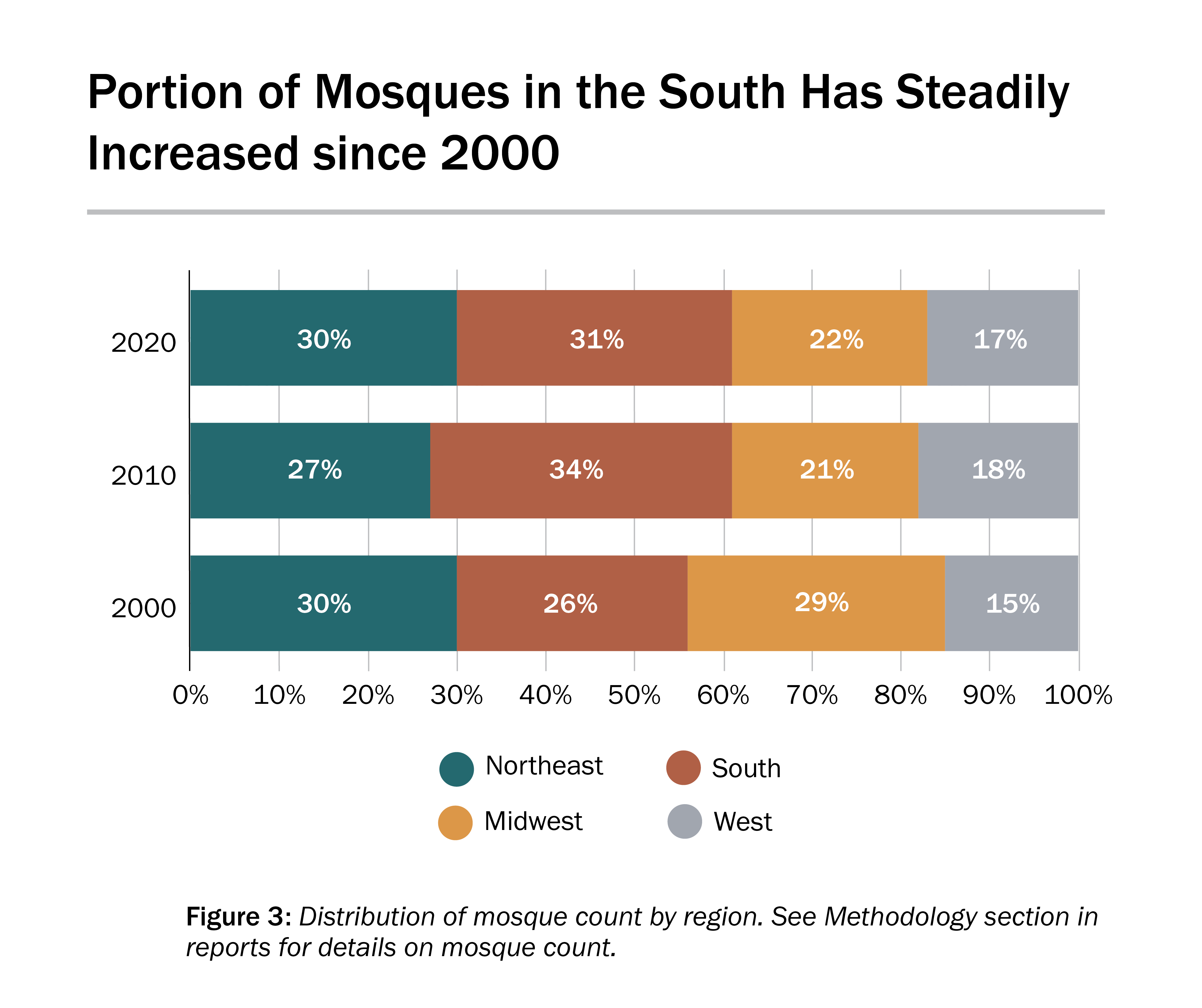

Not much has changed in the location of mosques. Mosques are found in every state in America, with the largest numbers being in New York, California, and Texas—representing 31% of all mosques. Large metropolitan areas have the largest number of mosques—led by New York City. The regions where mosques are located have also not changed much, although the slow growth of mosques in the South is a clear trend.

Urban-Suburban-Town Locations

The location of mosques in terms of the urban-suburban-town parameters are changing significantly. Mosques in downtown areas and in town/small city locations are decreasing. In 2010, 20% of mosques were in towns/small cities, but in 2020 that percentage is down to 6%. One of the reasons for this decline might be linked to the dynamic that the children of mosque participants are moving away to seek education and better jobs. Many town and small city mosques were established by doctors from overseas who were incentivized in past decades to set up practices in underserved locations. These doctors are now retiring, and mosque attendance is dwindling. The decrease in downtown mosques is most likely tied to the decline of African American mosques and the general move of immigrant mosques to the suburbs.

Mosques are moving and being established in suburbs. Mosques in older suburbs went from 21% in 2010 to 33% in 2020. Mosques in new suburbs went from 7% in 2010 to 15% in 2020. The age-old pattern of immigrants achieving financial success and moving away from cities seems to be repeating itself in the American Muslim community.

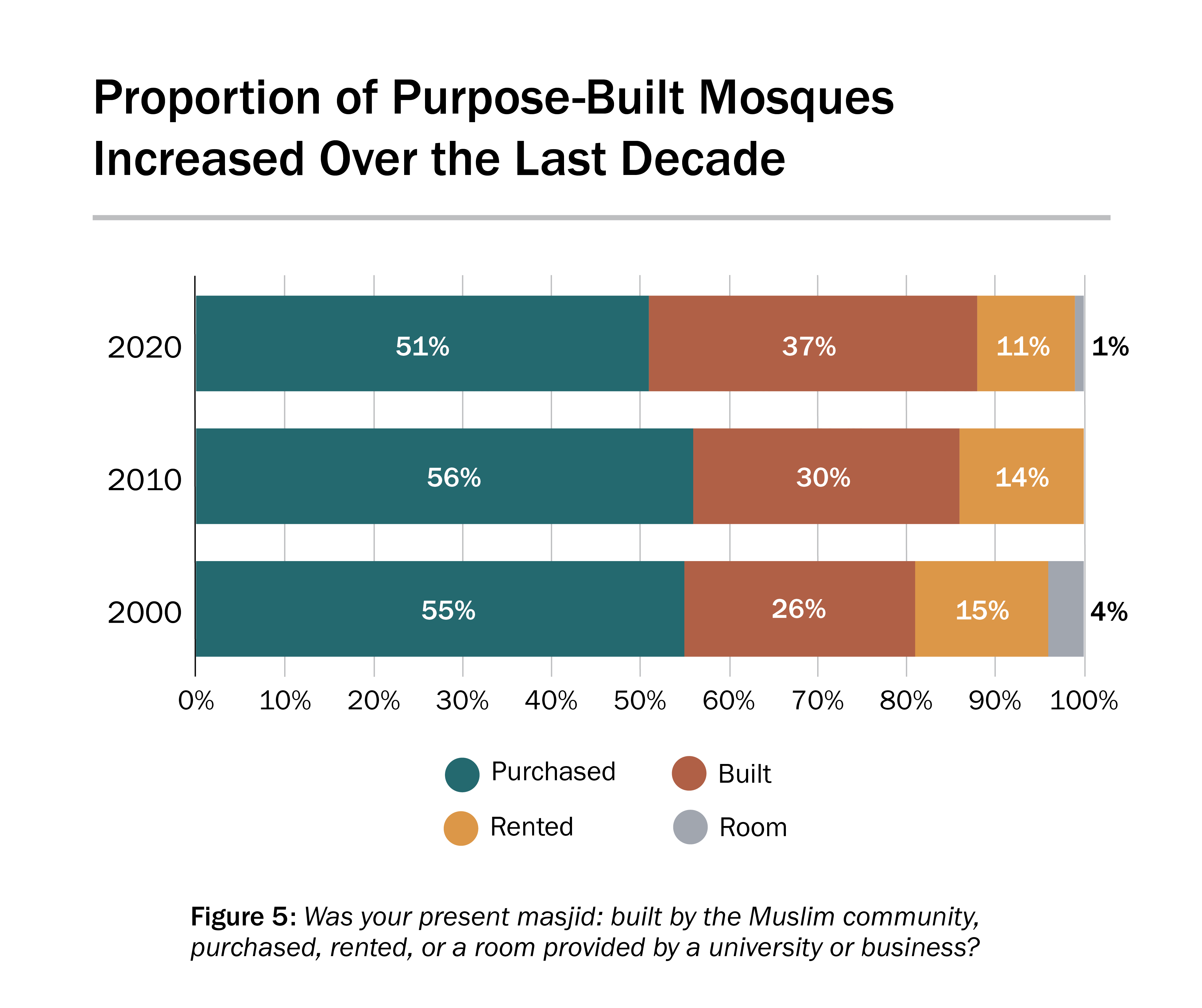

Mosque Buildings

The growth of the American mosque in number and size is joined with the steady increase in the number of purpose-built mosques. In 2000, 26% of all mosques were purpose-built, and in 2020 that percentage has increased to 37%. Nevertheless, the majority of mosques are purchased, ranging in structure from former churches to houses. The typical progression in the life of a mosque is its initial establishment in a rental facility where Jum’ah prayers and Sunday school are held, to a purchased facility with expanded space for Jum’ah and other activities, and, finally, to a facility that is built as a mosque.

The increased percentage of purpose-built mosques and the increase in the total number of mosques means that the actual number of purpose-built mosques has increased dramatically. In 2000, there were only 314 purpose-built mosques, but in 2020, that number was 1025. It might be surmised that the relatively young American Muslim community is still in a building phase, where money is going into capital campaigns as opposed to expanding staff or funding programs.

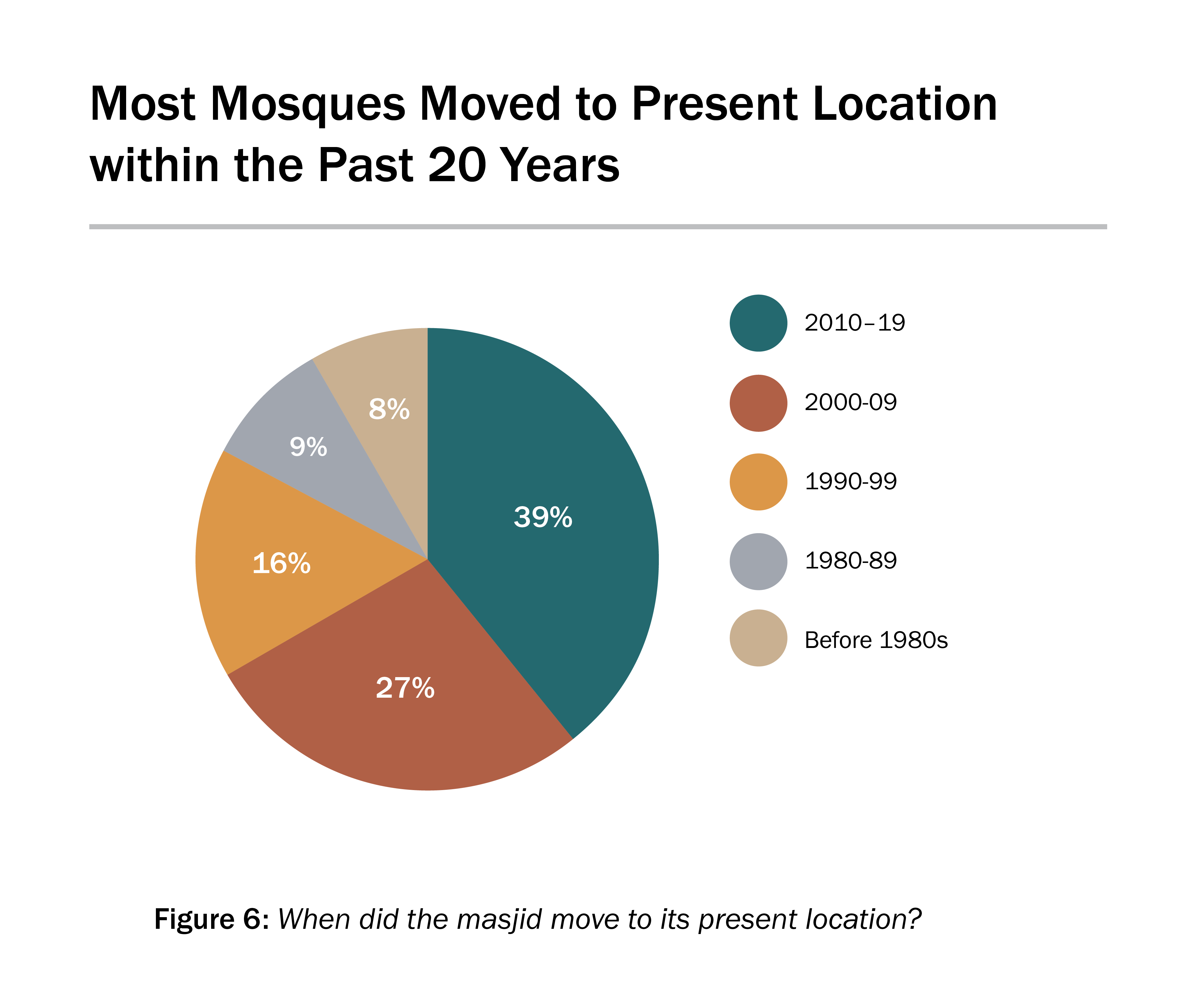

Year That the Mosque Moved to Its Present Location

Two-thirds (66%) of all mosques have moved to their present location since 2000, demonstrating again that mosques are still in the process of growing.

City and Neighborhood Resistance to Mosque Development

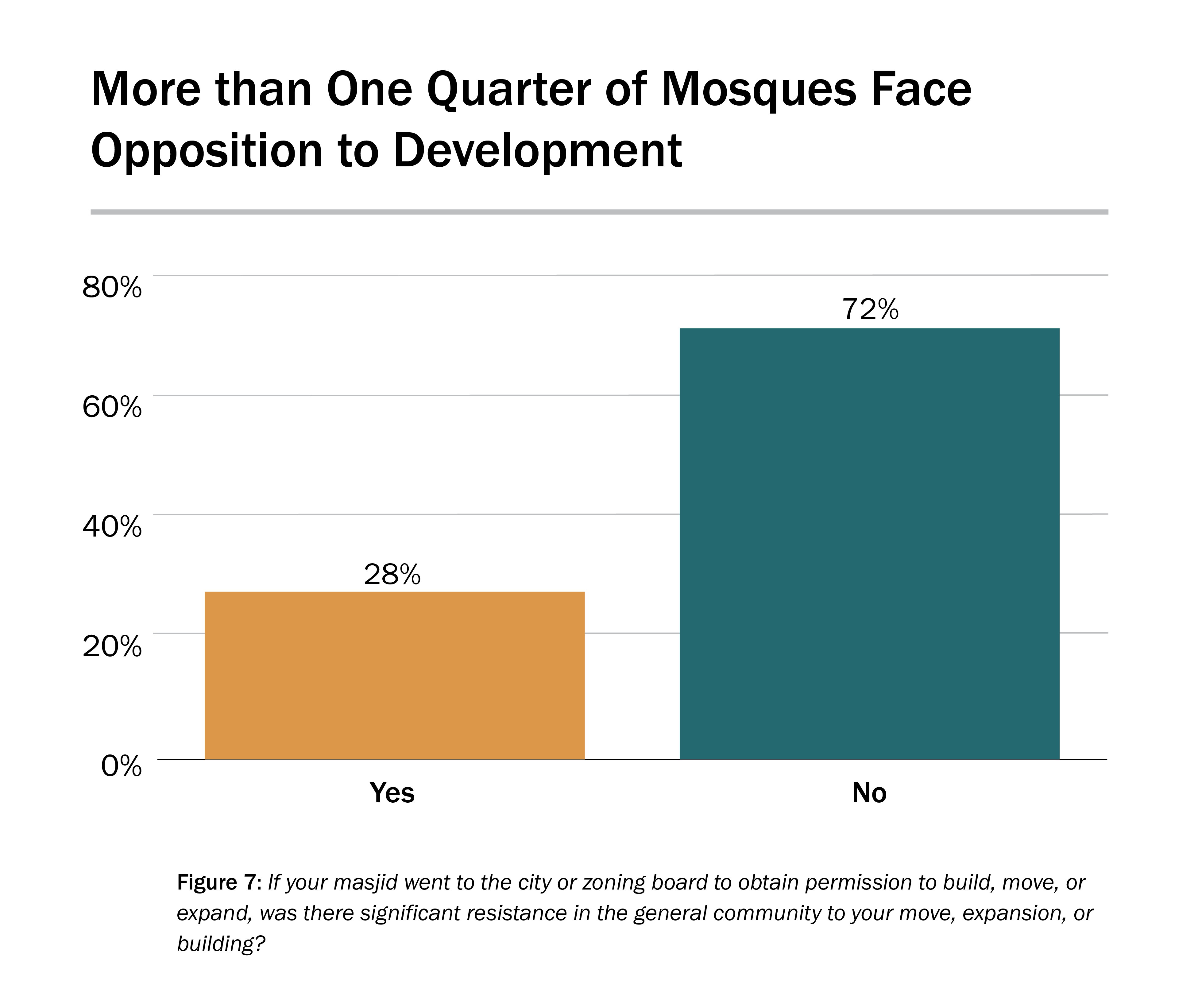

A new question in the 2020 Mosque Survey asked if the mosque had experienced any significant resistance from the city zoning board or the neighborhood when the mosque had to seek permission to build, move, or expand. Approximately 28% of mosques responded that they did meet resistance. In their comments, most mosque leaders mentioned that most of the resistance came from the neighborhood.

Comparing the decades when a mosque had to go to the city to seek permission to build, move, or expand, before the 1980s there was little resistance. From 1980-2009, about a quarter of mosques experienced resistance. The highest level of resistance has been most recently in the last decade (2010-2019): 35% of mosques experienced resistance. Apparently, negative attitudes toward Muslims have grown in the last decade.

Mosque Concern for Security

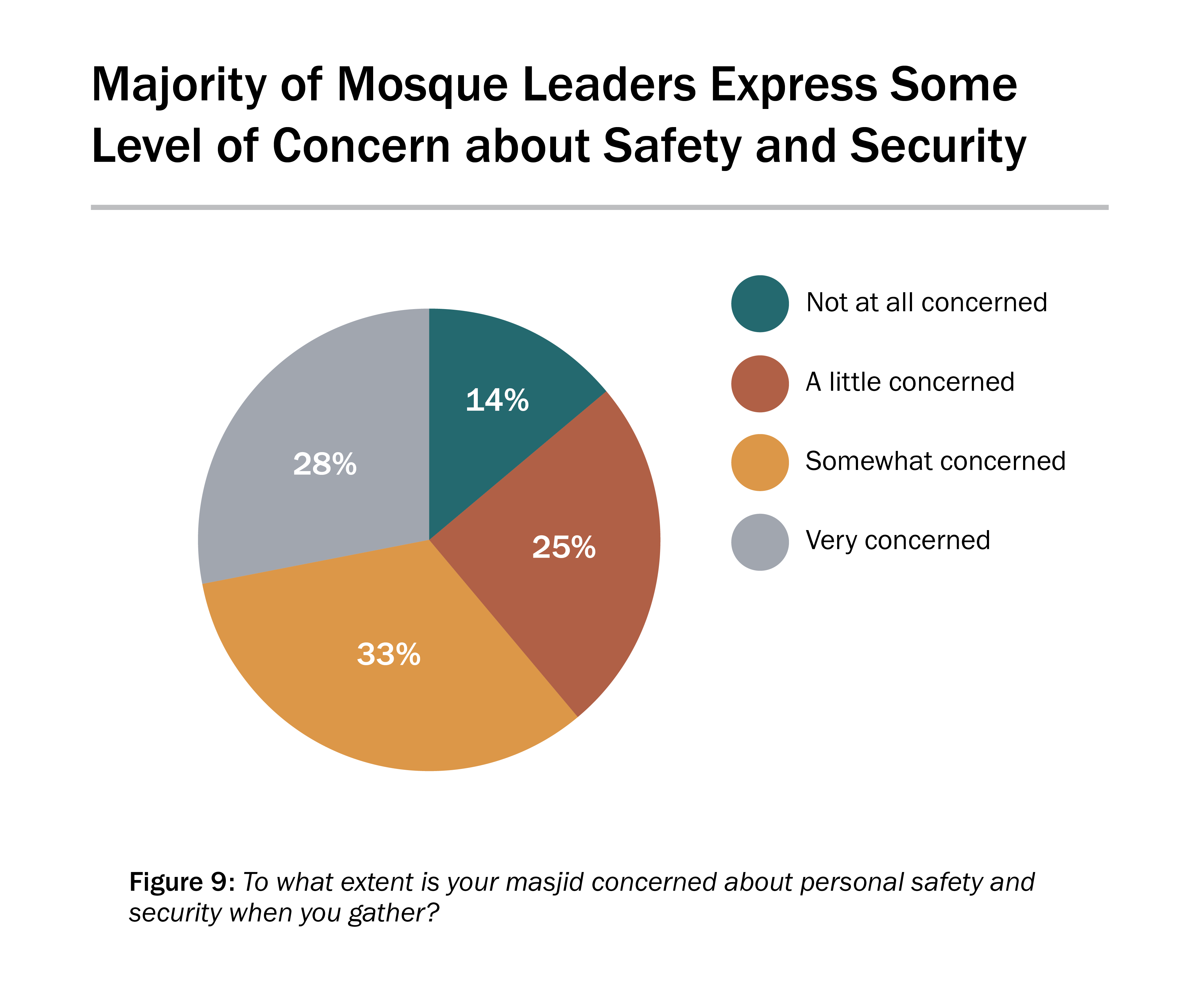

Another new question in the 2020 Mosque Survey concerned mosque security, especially in the aftermath of the New Zealand tragedy. Surprisingly, most mosques do not evince a great concern for security. Only 28% of mosque leaders said that they were very concerned.

These figures might be misleading, because many mosque leaders seemed to respond to the question as if it were a theological question. They would preface their answer by statements like, ‘We trust in Allah.’ Possibly, being very concerned might be associated with not trusting in God enough.

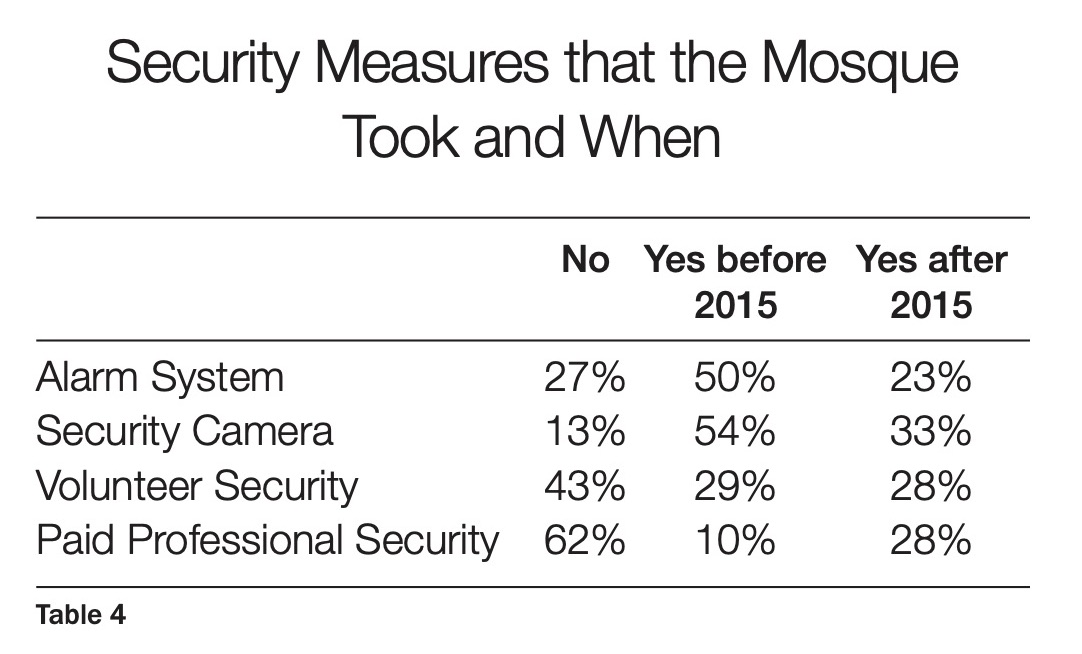

A follow-up question asked about specific security measures that the mosque might have taken and when they took these measures. The results show that most mosques had taken some precautions before 2015, except for paying for paid professional security which increased dramatically after 2015: 10% of mosques had paid professional security before 2015, but after 2015, 28% had paid security.

.

Mosque Participants

Jum’ah (the Friday Congregational Prayer) Attendance

Jum’ah attendance continues to grow. Average attendance in 2020 is 410, which is a 16% increase over the 2010 Jum’ah attendance of 353. Undoubtedly, the increase in Jum’ah attendance is driven by the larger number of Muslims, but the increase can also be attributed to the phenomenon of “build it and they will come.” Many mosque structures in 2020 are larger, more attractive, and more comfortable; many mosque leaders remark that as soon as they expanded or built their mosque, the mosque was full. The greater number of attendees is also attributable to the fact that to accommodate the growing number of attendees, 21% of mosques initiated a second or even third Jum’ah prayer service.

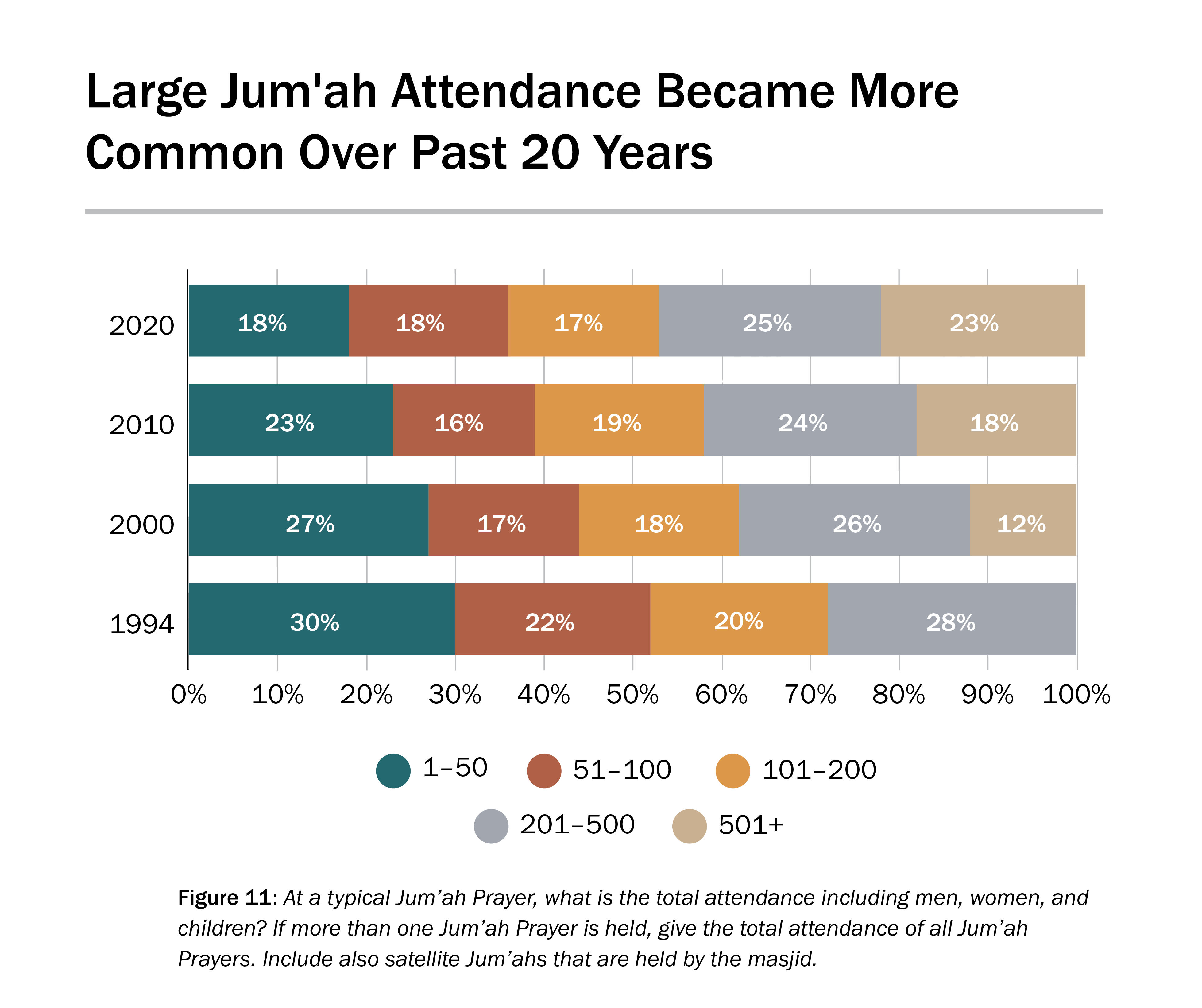

The growth in Jum’ah attendance is reflected in the slow decrease of small mosques and the slow increase of larger mosques. In 2000, 27% of American mosques had a Jum’ah attendance of 50 or less, and in 2020 that number decreased to 18%. In 2000, 12% of all mosques had a Jum’ah attendance of over 500 while in 2020, 23% of mosques had attendance over 500.

The increase of Jum’ah attendance is also reflected in the fact that 72% of mosques reported a 10% or greater increase over the last five years.

The emergence of the mega-mosque since 2000 is also an unmistakable phenomenon. A mega-mosque, like a mega-church, is defined as a congregation with over 2000 attendance at the weekly congregational service. In 2010, 2% of all mosques could be defined as a mega-mosque, and in 2020 that figure has doubled to 4%.

Total Number of Mosque Participants

The total number of participants is measured by the number of people who attend the mosque at least for the Eid prayer service. In 2020, an average of 1,445 Muslims attend at least Eid prayer in the American mosque. This figure is a 16% increase from the 2010 figure of 1,248 participants. Multiplying 1,445 participants times 2,769 mosques, the total number of Muslims who attend at least Eid—constituting the total number of mosqued Muslims—equals a little over 4 million Muslims.

Conversion to Islam

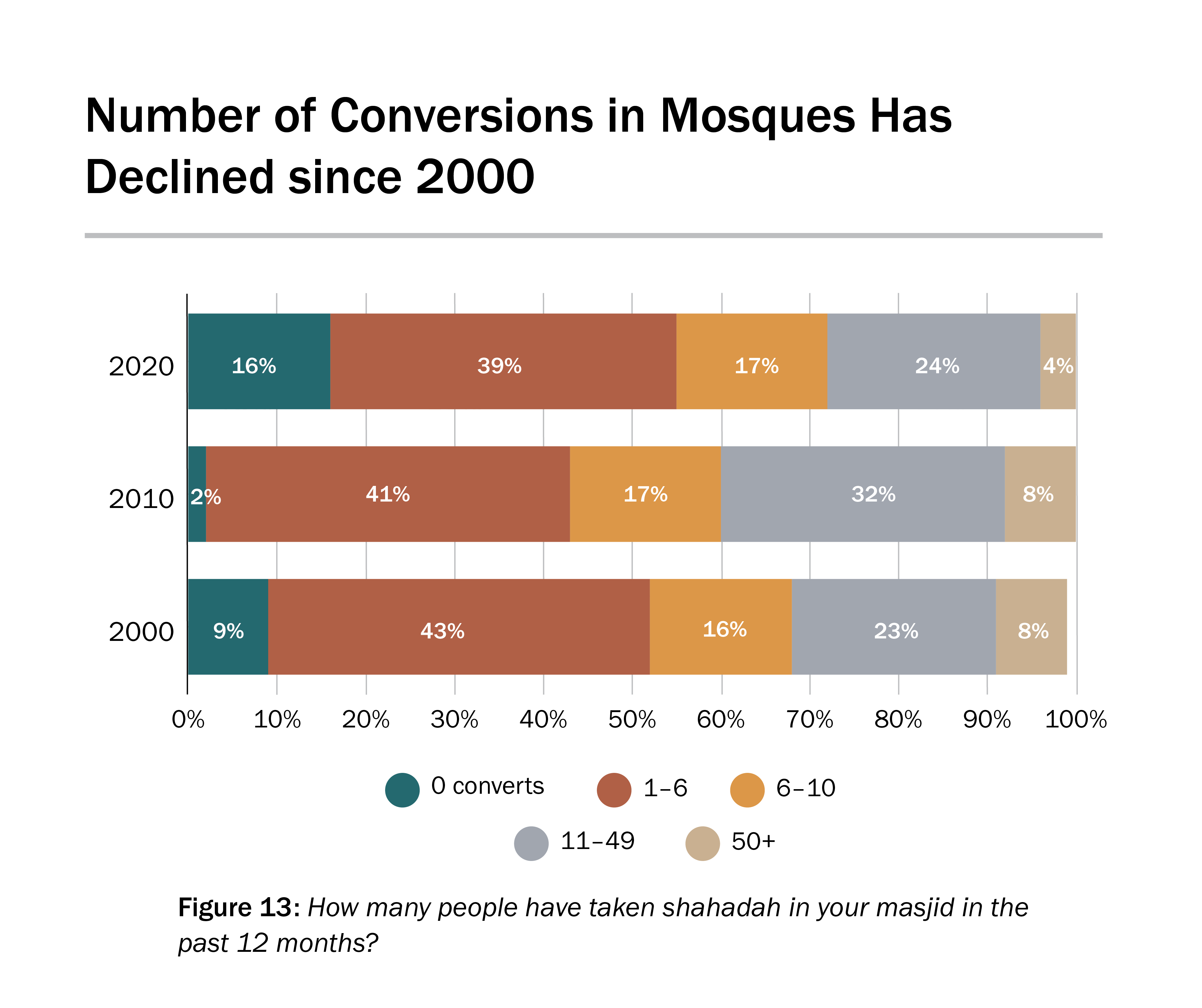

The conversion rate in mosques has decreased substantially over the last decade. In 2000, the number of conversions per mosque were 16.3; in 2020, the rate was 11.3—a 31% decrease from 2000. More mosques in 2020 reported that no conversions took place in their mosques, as compared to other decades when almost all mosques had some conversions. In 2010, only 2% of mosques had zero conversions, but in 2020 16% of mosques reported no conversions. Also, the number of mosques that largely fueled the number of conversions has decreased: 8% of mosques in 2010 had over 50 conversions; in 2020, that percentage was only 4%.

In terms of the actual number of converts as opposed to the percentage of converts per mosque, the figures show a slight decrease in converts from 2010 to 2020. In 2010, there were 33,222 converts, and in 2020, the figure was 31,290. Overall, conversions have plateaued.

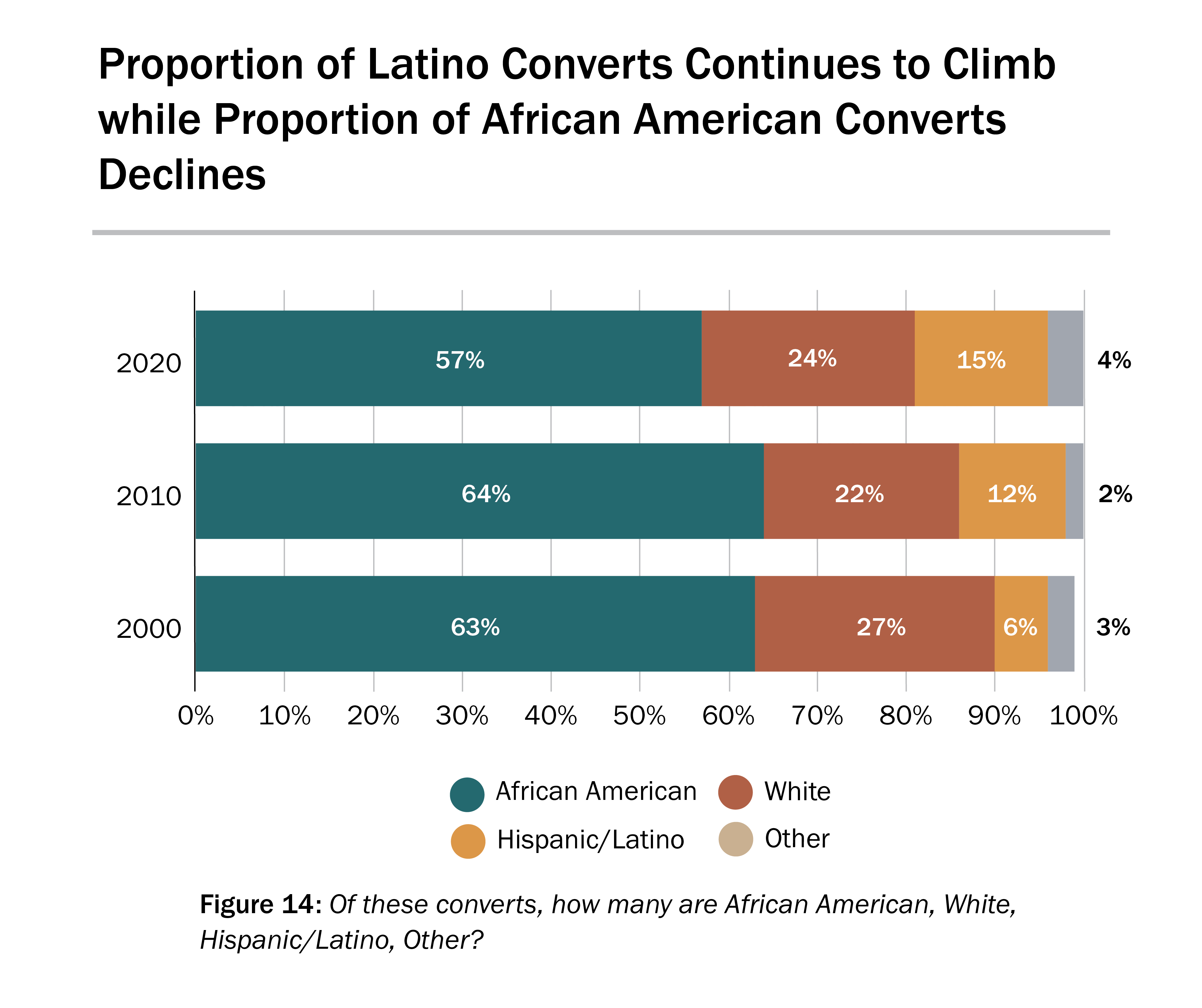

The lower percentage of converts per mosque and the slight decrease in the actual number of converts are possibly linked to the lower number of African American converts and the lower number of African American mosques that are recording large numbers of converts. In 2010, 64% of all converts were African American, and in 2020 that percentage decreased to 57%. In 2010, 11% of African American mosques had 50 or more converts, but in 2020 only 7% of African American mosques reported 50 or more converts.

Another statistic of note is the continued increase of the number of Latino/Latina converts. In 2000, only 6% of all converts were Latino/Latina, but in 2020 that percentage is now 15%.

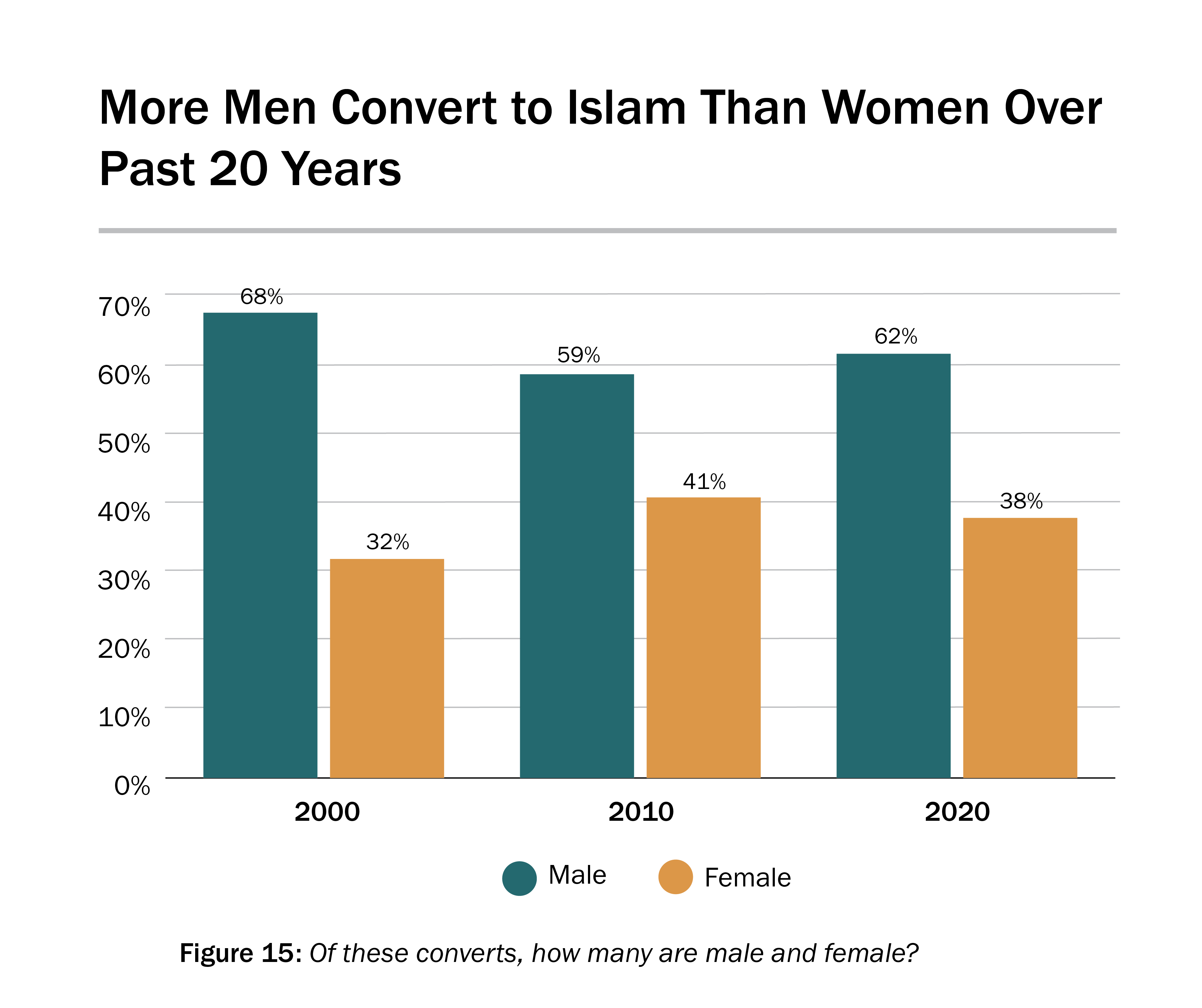

The gender of converts has not changed over the decades: the ratio has remained about 60/40 in favor of men.

Mosque Ethnicity

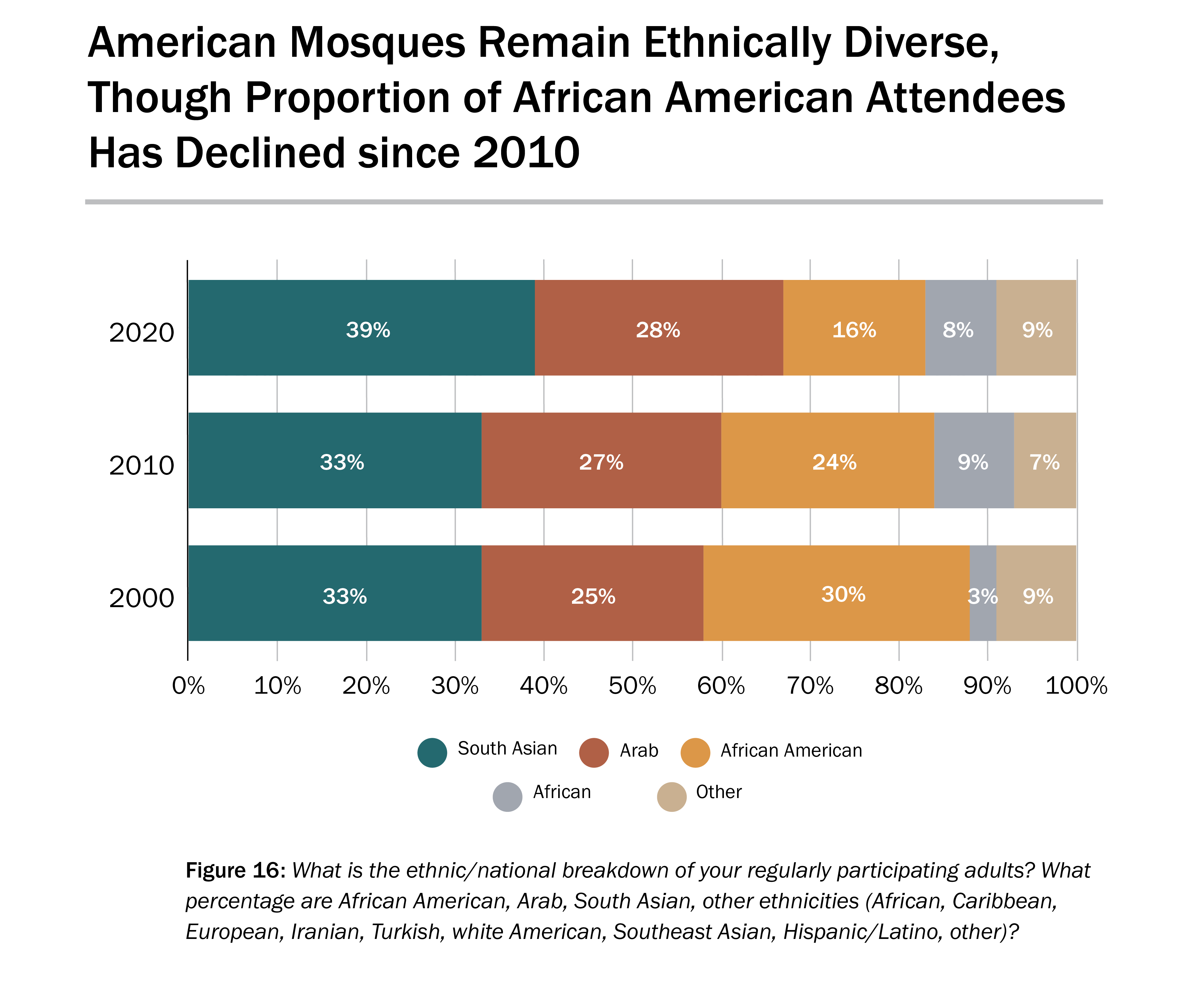

The American mosque remains one of the most diverse religious bodies in America, and the Friday congregational prayer (Jum’ah) remains the greatest demonstration of that diversity. Whether inner-city or suburban, numerous ethnic/national peoples attend these mosques. Only 4% of all mosques have only one ethnic/national group that attends that mosque. (A mosque with only one ethnic/national group is defined as a mosque with 90% or more attendance of one ethnic group.)

The one noticeable change in the ethnic mixture of mosque participants is the decrease in the number of African American Muslims. In 2010, 24% of all mosque attendees were African American, but in 2020 only 16% were African American, representing a 33% decrease. More study is needed to determine the dynamics that are leading to this phenomenon, but one possible reason is that the lower conversion rate of African Americans means that the African American Muslim population is holding steady while the overall number of American Muslims is experiencing significant increases. Therefore, the overall percentage of mosque attendees who are African American is decreasing. In other words, the actual number of African American Muslims has not decreased but plateaued, and, as a result, its overall percentage in the growing Muslim population is decreasing.

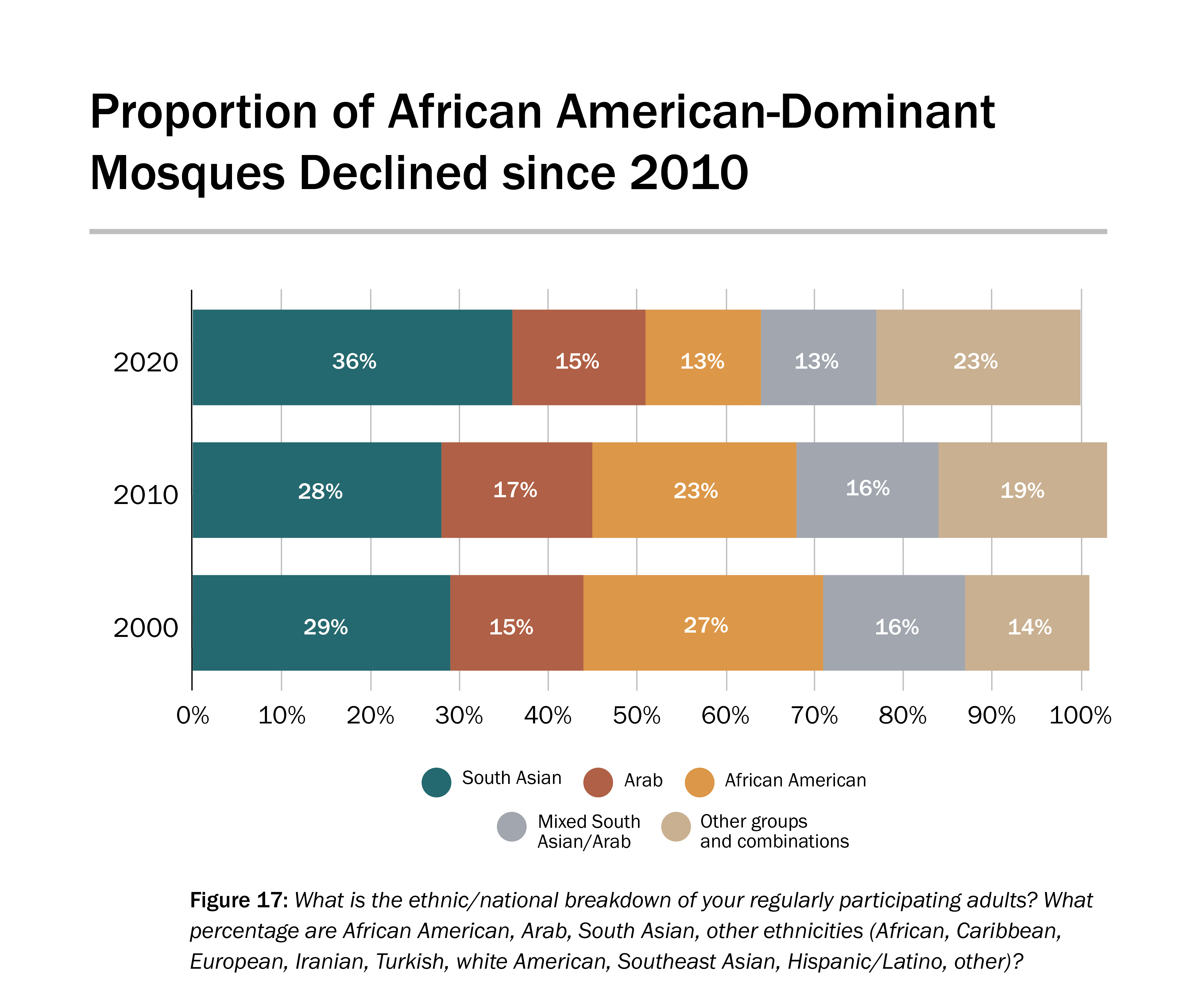

Mosques Dominated by an Ethnic/National Group

Although diverse, approximately three-fourths of mosques have one ethnic group that dominates the mosque. In other words, many ethnic groups might attend the mosque, but there is one group that has a predominant number of attendees. (See the note below the chart of what constitutes a mosque with one dominant group.) More than one-third of all mosques (36%) are largely attended by South Asians, which include Pakistanis, Indians, Bangladeshis, and Afghanis.

The one figure of note is the decrease in African American mosques: in 2010, 23% of all mosques were African American mosques, and 2020 that figure was 13%—a 43% decrease. There are a few possible explanations for this phenomenon. (1) One explanation is that a substantial number of African American mosques are closing. Of the 134 African American mosques that were sampled and included in the 2010 Mosque Survey, 20 have closed and are no longer found in the 2020 list of all mosques—a 15% decrease. Many of these mosques that closed were small mosques in either towns/small cities or big cities; the number of attendees dwindled in the towns/small cities and/or competition overwhelmed them in the large cities. (2) Another contributing factor is that fewer African American mosques are being established, so the overall percentage of African American mosques is decreasing as the number of immigrant mosques increase. Up until 1990, on average 22% of all new mosques were African American. In the decade of 2010-2019, only 8% of new mosques were African American. (3) A readily observable factor is that attendees at many historically African American mosques are no longer dominated by African Americans. In other words, Muslims of various ethnicities are attending African American mosques in greater numbers, such that the mosque can no longer be classified statistically as an African American mosque. Clearly, immigrant and second-generation Muslims feel more comfortable attending historically African American mosques, and African American Muslims are welcoming to all Muslims.

Age Groups of Mosque Participants

A new question in the 2020 Mosque Survey asked about the age groups that attend the mosque. Mosque leaders had a hard time answering this question because no records are kept on the ages of mosque participants. So, at best, the results of this question can be viewed as a very rough snapshot of the mosque community.

The analysis of age groups within mosques is a case of good news/bad news. The good news is that in comparison with churches, mosques are doing quite well. Among the age group 18-34, which is roughly the age group of Generation Z and young Millennials, 24% of the mosque participants are from this age group as compared to 11% in churches (see Faith Communities Today in Sources). Mosques have much fewer participants over 65 years of age: 14% of mosque participants are 65 and above, compared to 29% in churches. ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll also finds that younger Muslims are more likely to attend religious services, compared with their counterparts in the general public. Specifically, 54% of Muslims ages 18-34 attended a religious service (aside from weddings and funerals) in the year prior to the survey, compared with 26% of 18-34 year-olds in the general public.

The bad news becomes visible in comparing the results of the Mosque Survey—minus the 1-17 age group—with the figures from ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll.

The most striking comparison is the 18-34 age group, which again is roughly the Generation Z and young Millennial age group. Among the total American Muslim population, about half (54%) are aged 18-34, but among mosque attendees the percentage is 29%. Significantly, therefore, fewer Muslims aged 18-34 are attending the mosque than are in the total population. Thus, while mosques do better than churches in attracting Generation Z and Millennials, mosques overall are not attracting a sizable portion of that age group. The largest age group that attends the mosque (and largely controls mosques) are those aged 35-65. Also, as might be expected, significantly more Muslims above the age of 65 attend the mosque.

In recognition of the mosque’s difficulty in attracting young adults (18-34), 60% of mosque leaders responded that they are not satisfied with the involvement of young adults.

Mosque Attendees with Special Needs

A new set of questions in the 2020 Mosque Survey focused on mosque participants with special needs. Approximately 40% of all mosques answered that Muslims with special needs attend their mosque. Among these mosques, an average of three Muslims with special needs attend. The few mosques which have up to 20 Muslims with special needs are mosques that are extremely welcoming and accommodating to people with special needs, providing facilities, classes, and a support group.

Over three-fourths (78%) of mosques have wheelchair accommodations at their entrance. Undoubtedly, most mosques have this accommodation because it is required by law. The only other accommodation that mosques provide is large-print Qur’ans: 12% of mosques indicated that they make available large-print Qur’ans.

.

Mosque Administration

The Imam

In the 2020 Mosque Survey, 84% of all mosques have an imam. The term imam literally means someone who is out front, and in usage it can refer to the regular prayer leader of the ritual prayer (Salah) in a mosque or the religious leader and religious authority in a mosque. The position and role of the imam in the context of the American mosque is unique in that the imam in the Muslim world is traditionally simply a prayer leader—not a pastor and leader of a congregation. And considering that the American mosque is a relatively young institution, it is understandable that the position and role of the imam is still in the process of being defined.

Age of the Imam

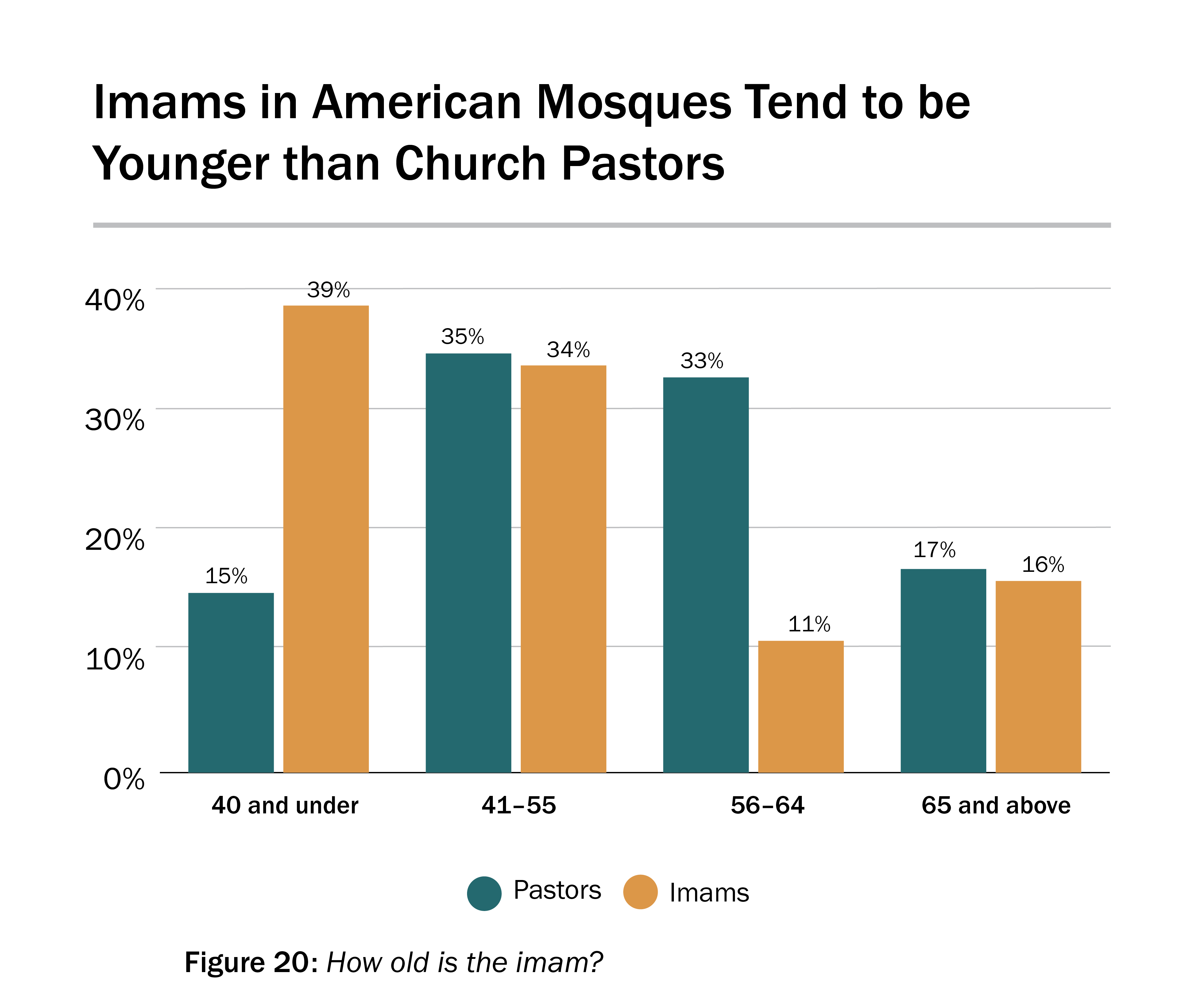

In 2010, the average age of imams was 48 years, and in 2020 it is the exact same average. This is a relatively young age for imams when compared to pastors in Christian churches, where the average age is 56 years. The Barna Group (a research center focused on the Christian church) determined in their 2017 study that 15% of church pastors were 40 years or younger (see Barna Group in Sources). In comparison, the 2020 Mosque Survey found that 39% of all imams were 40 and younger.

The average age of African American imams is 57, which is much higher than non-African American imams whose average age is 47. In 38% of African American mosques, the imam’s age is 65 years and older. In mosques dominated by immigrant groups, only 12% of their mosques have imams aged 65 or above. Leadership in African American mosques is clearly aging—possibly one of the problems in attracting African American young adults and new attendees.

Employment Status of Imams

Half of all mosques have a full-time paid imam, which marks a steady improvement since 2000. In 2000, only one-third (33%) of mosques had a full-time paid imam, and in 2010 it was 43% of all mosques. Conversely, the percentage of mosques with a volunteer imam has steadily decreased since 2000. Almost one-fourth (24%) of mosques in 2020 have a volunteer imam as compared to 42% in 2000.

Most volunteer imams are in African American mosques: 66% of all volunteer imams serve in African American mosques. The decline in volunteer imams is linked to the lower percentage of African American mosques.

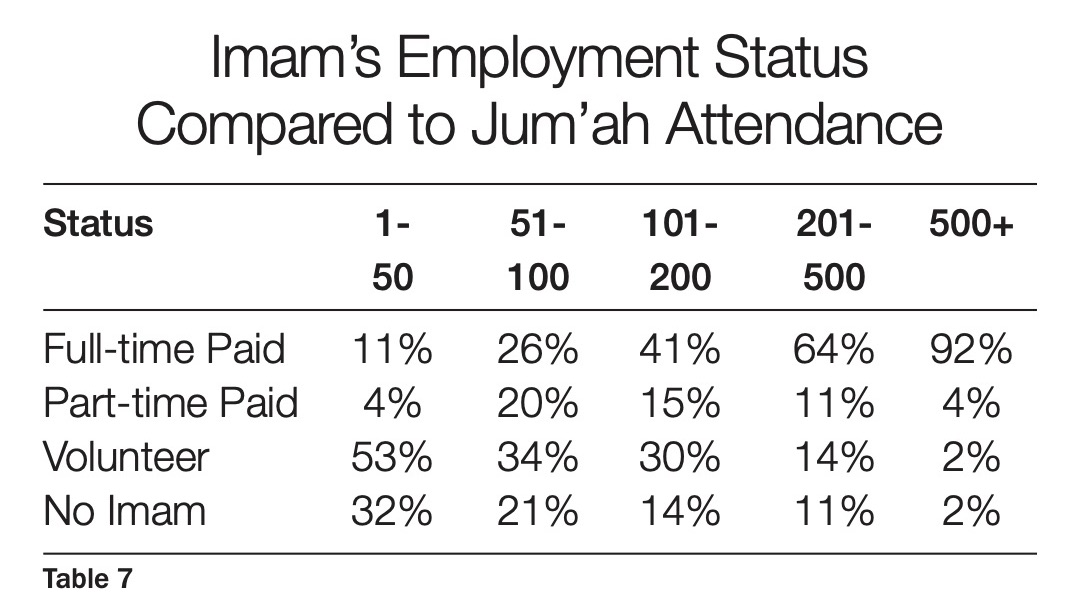

Having a full-time paid imam is tied to mosque attendance and budget. The median Jum’ah attendance for a mosque that has a full-time paid imam is 475. The median budget for a mosque that has a full-time paid imam is $180,000. Comparing Jum’ah attendance, 64% of mosques with attendance of 201-500 people have a full-time paid imam.

All the figures for full-time paid imams are very different from congregations of other faith groups. While 50% of mosques have a full-time paid imam, over 71% of all congregations have a full-time paid pastor. For churches, the common wisdom is that a church with a full-time pastor requires a Sunday attendance of 100, but the standard for mosques is a Jum’ah attendance of 475. Churches apparently place a higher priority in hiring a full-time paid pastor. Another possible deduction is that the 100 church participants give a lot more to the church to reach a budgetary threshold to hire a pastor than the 475 mosque participants. (See Thomas Rainer in Sources.)

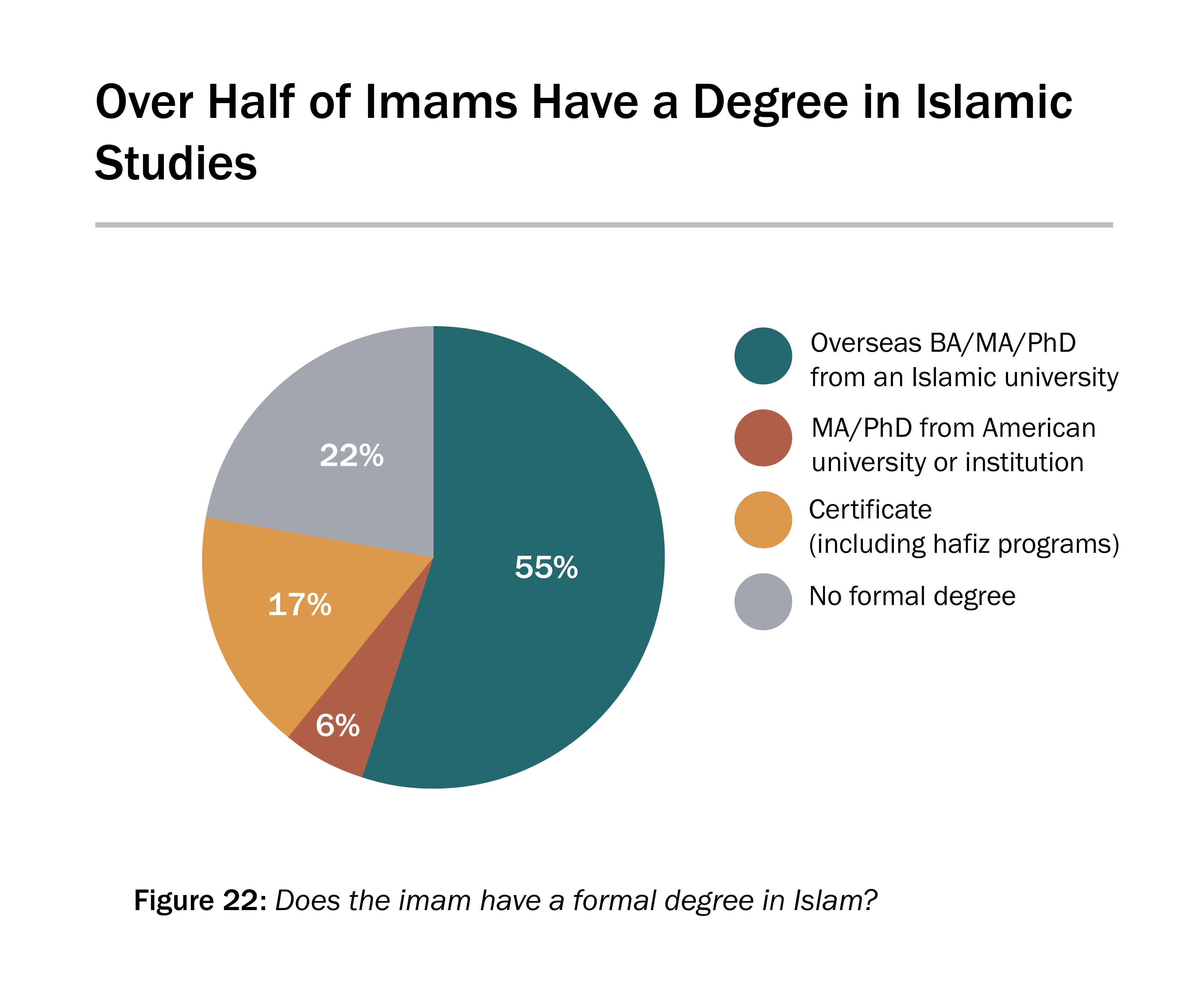

Imam Education

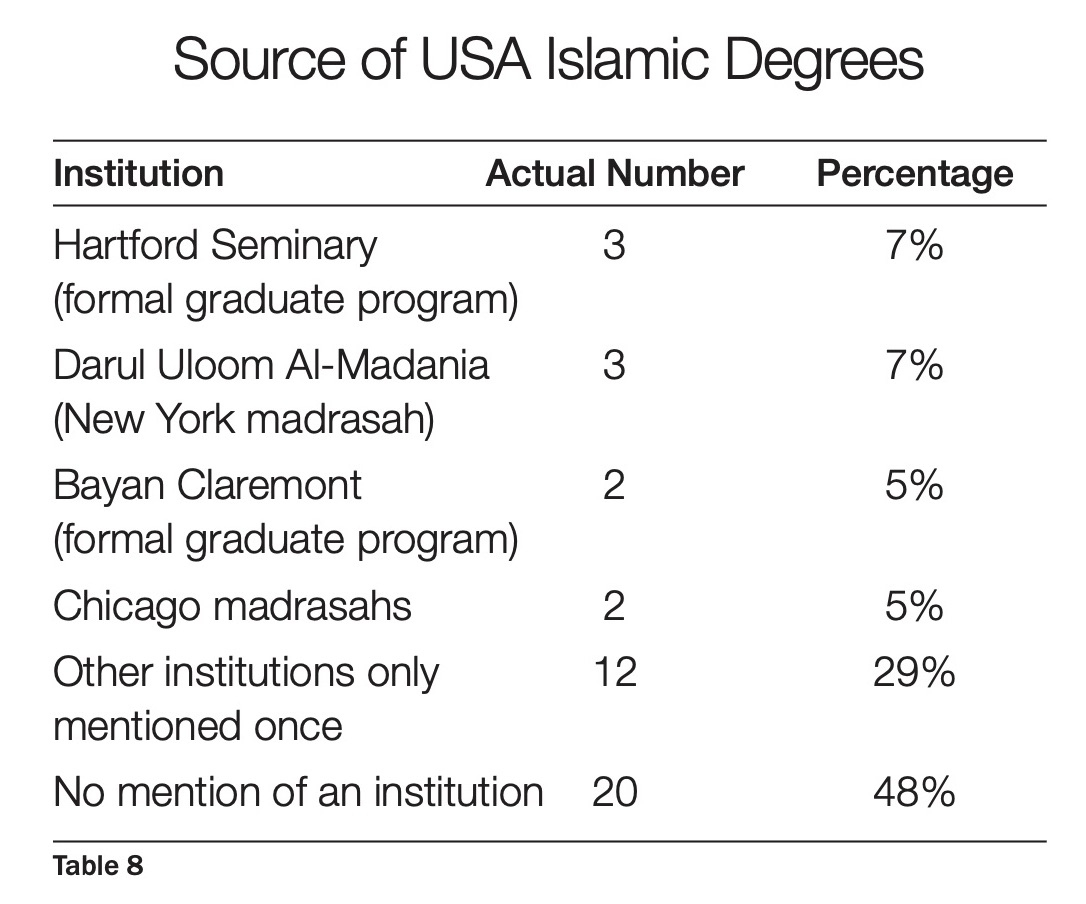

Over half (55%) of imams have a BA, MA, or PhD in Islamic studies from an overseas university. Approximately 6% of all imams have a degree in Islamic studies from an American university or institution. Thus, 61% of imams have an Islamic degree, which is an increase from 2010 when only 48% of imams had an Islamic degree. Clearly, American imams are more formally trained in Islam than in the past.

For those few imams who received an Islamic degree in America, there is no one institution that dominates. The absence of a preeminent Islamic seminary in America is a major hurdle for increasing the number of imams who are trained in America as opposed to going overseas to study.

The imams, who received an Islamic degree (BA, MA, PhD), obtained their degree from 35 different countries. However, Egypt (Al-Azhar University) and Saudi Arabia (Islamic University of al-Madinah) are the most common source of their degrees—34% come from these two countries. South Asia was the source of 14% of the degrees.

National Origin of Imams

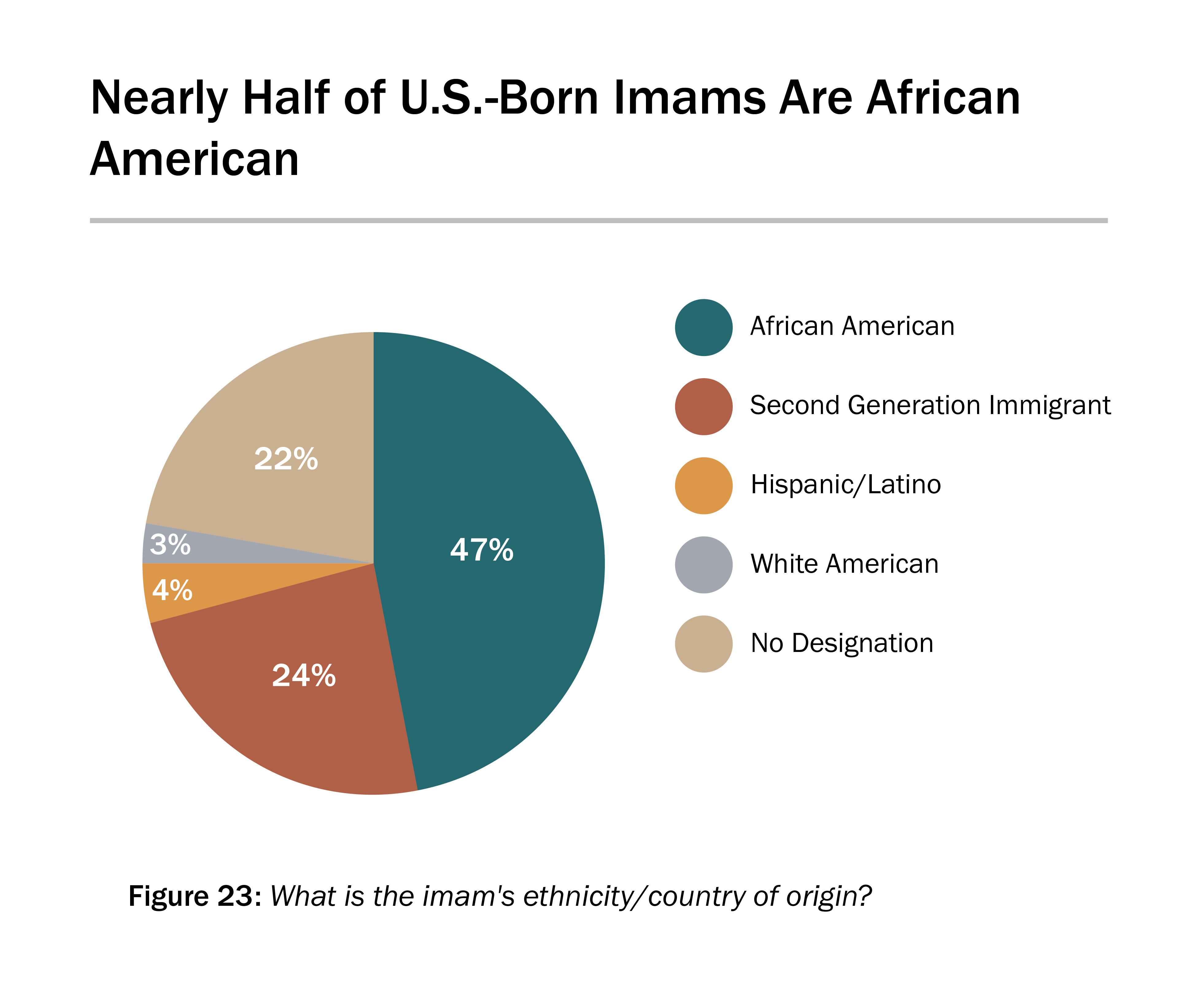

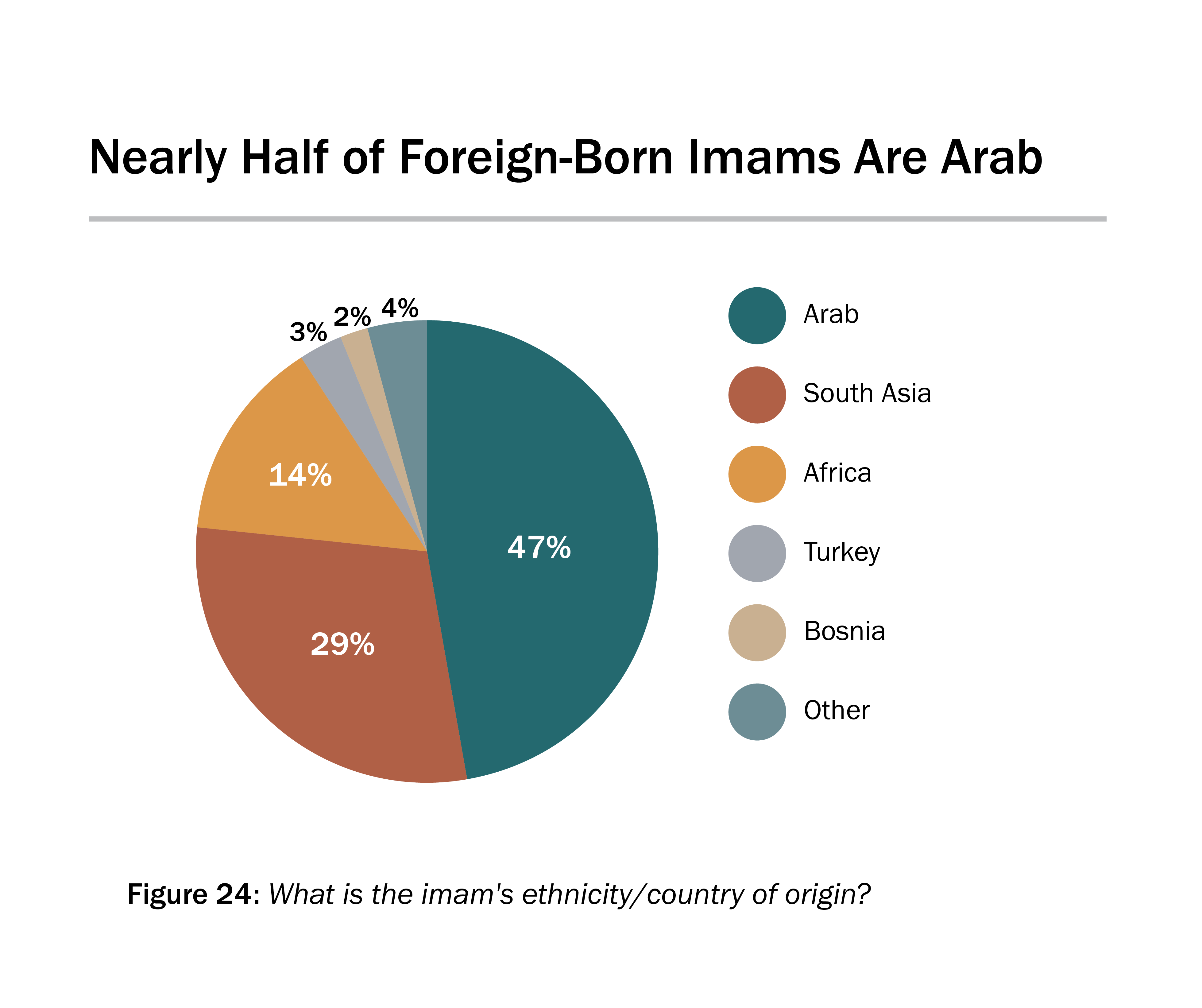

Imams are from 41 countries—a remarkably diverse group. About two-thirds (68%) were born abroad and about one-third (32%) were born in the US. These percentages are virtually the same as in 2010.

Among US-born imams, the largest group are African Americans, but a significant number are second-generation Muslims (children of immigrants).

Of those imams born abroad, almost half are from Arab countries, with Egypt being the origin of most Arab imams.

The large percentage of Arab imams points to the phenomenon that many non-Arab mosques have Arab imams. Among South Asian mosques, 31% have an Arab imam; among mosques that are mixed Arab and South Asian, 61% have an Arab imam.

The vast majority of full-time paid imams are foreign-born, but the percentage of foreign-born imams has decreased, and the percentage of US-born, full-time paid imams has increased. In 2010, 85% of full-time paid imams were born outside of America, but in 2020 78% were foreign born.

One of the discussions within many American mosques is the desire to have more US-born imams who can better communicate with youth and young adults. The increase in the percentage of American-born imams points to a trend that will no doubt continue in the future.

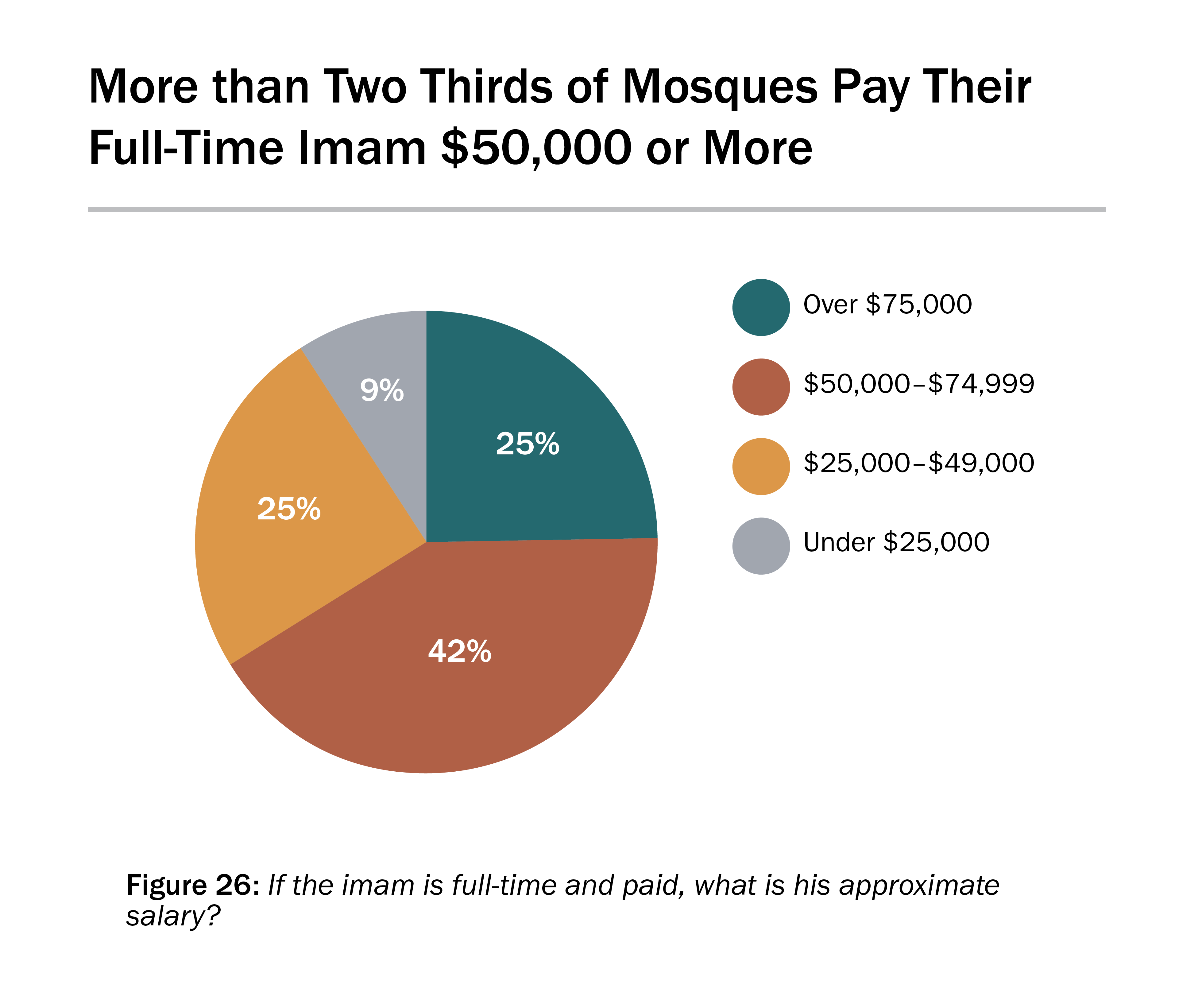

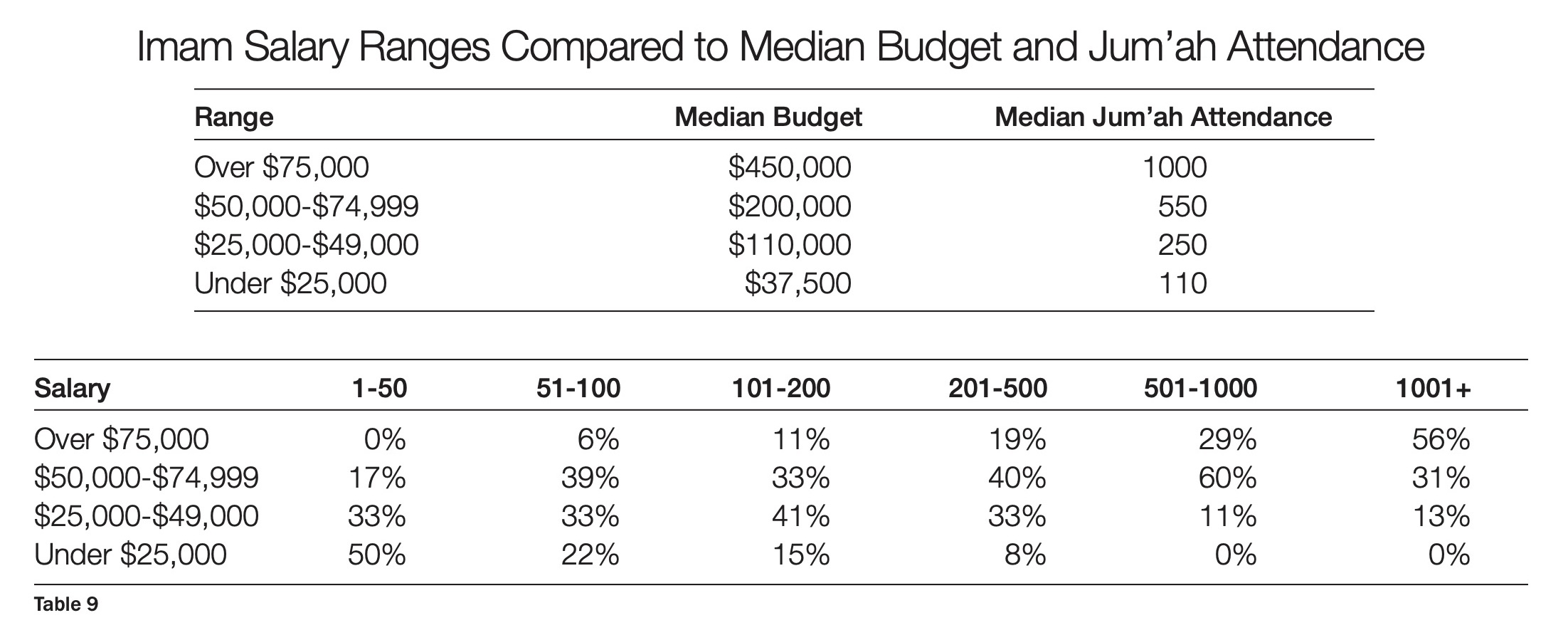

A new question in the 2020 Mosque Survey was asked about the salaries of full-time paid imams. Ranges were offered from over $75,000 to under $25,000. A substantial number (77%) of mosques with full-time paid imams answered the question, so the results should be viewed as reliable.

These figures are very respectable when compared to pastor salaries.

As might be expected, the imam’s salary is linked to mosque size and budget.

Mosque Governing Structures

There is no one model that typifies mosque governance. This is not surprising taking into consideration that there is no governing model to be inherited from overseas and that there is no centralized body in America to dictate mosque policy. In addition, the American mosque is a relatively young institution, and, therefore, a consensus on a model of mosque governance is evolving.

Almost half (48%) of mosques have only one governing body that runs the daily operations of the mosque. Sometimes that body is called a board (usually board of directors) and sometimes it is called an executive committee. Approximately 28% of mosques have two governing bodies: a board (usually called a board of trustees) which typically provides oversight and an executive committee which operates the day-to-day affairs of the mosque. Approximately 12% of mosques have an oversight board of trustees, an executive committee involved in management and an executive director who focuses on management. In many cases the executive director is paid, and, therefore, assumes greater responsibilities than the executive committee.

The position of executive director is an emerging phenomenon in mosques. In 2020, 19% of mosques had an executive director, whether full-time or part-time. Instead of the volunteer president leading the efforts to manage the day-to-day affairs of the mosque, the executive director is appointed or hired to take the responsibility of running the mosque.

Over three-fourths of mosques (76%) are managed by a volunteer executive committee. The dependence on volunteers to run mosques is a major impediment to mosque development.

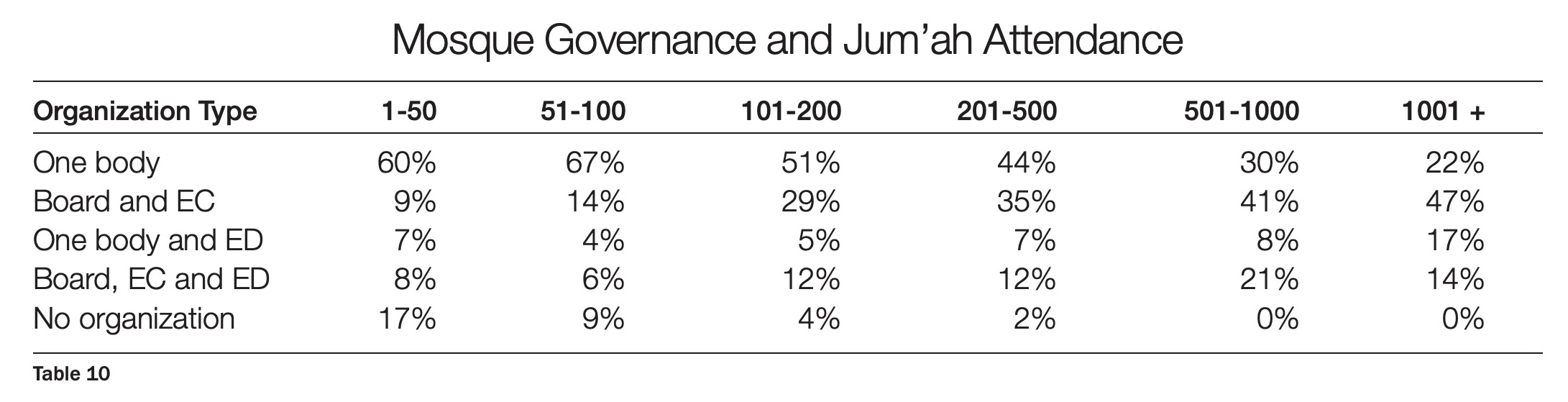

The size of the mosques does influence the type of mosque organizational structure. One governing body is more prevalent in smaller mosques and decreases as the mosque grows in size. A board of trustees with an executive committee is more common in larger mosques.

How Are Governing Bodies Put in Place?

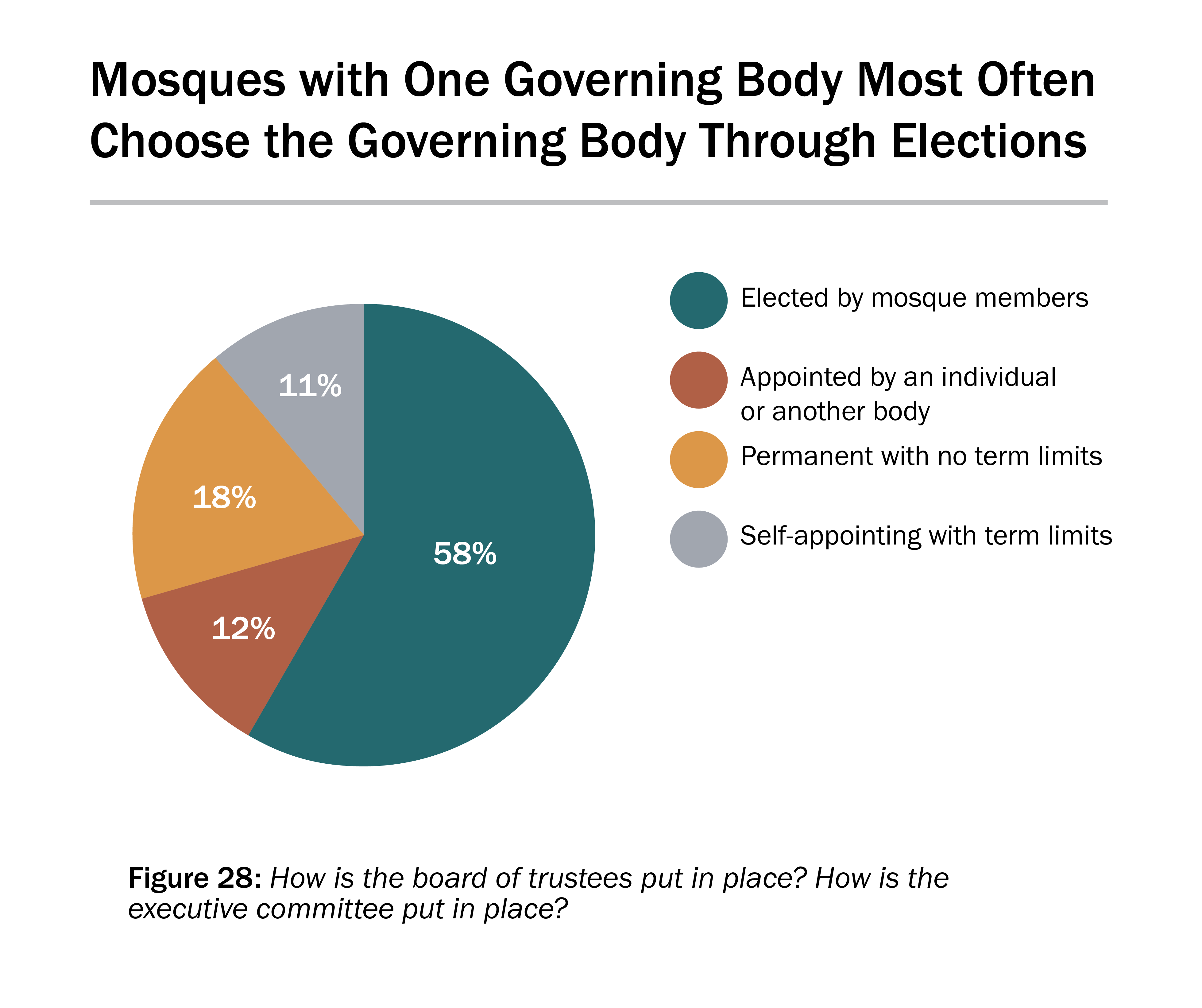

The mosque which has only one governing body, whether called a board of directors or executive committee (EC), is in most cases (58%) put in place by an election of the mosque members. A large segment (41%) of mosques has their one governing body appointed or permanent, usually composed of the founders. In those mosques where the one governing body is appointed, the appointment is done by the imam (typically African American mosques where the imam controls all aspects of the mosque) or appointed by the founder(s) of the mosque. The permanent board/executive committee is usually formed early in the life of the mosque by its founders and early activists. The self-appointing board/executive committee refers to a body whereby members have term limits and replacements are elected by the board/executive committee. This type of arrangement is usually an evolution of the permanent governing body, whereby the governing body decides that it is best to have some regular turn-over but to limit it to candidates that are selected by the governing body.

Many mosque leaders who do not hold elections for governing bodies often express their dislike for elections because of the exposure of the mosque to in-fighting or being taken over by a hostile group. In their view, it is safer to keep the governance of the mosque in the hands of a few people, whether founders or long-time activists in the mosque. In rare instances, mosque leaders give an Islamic rationale, arguing that there is no precedence for elections in the authoritative sources of Islam.

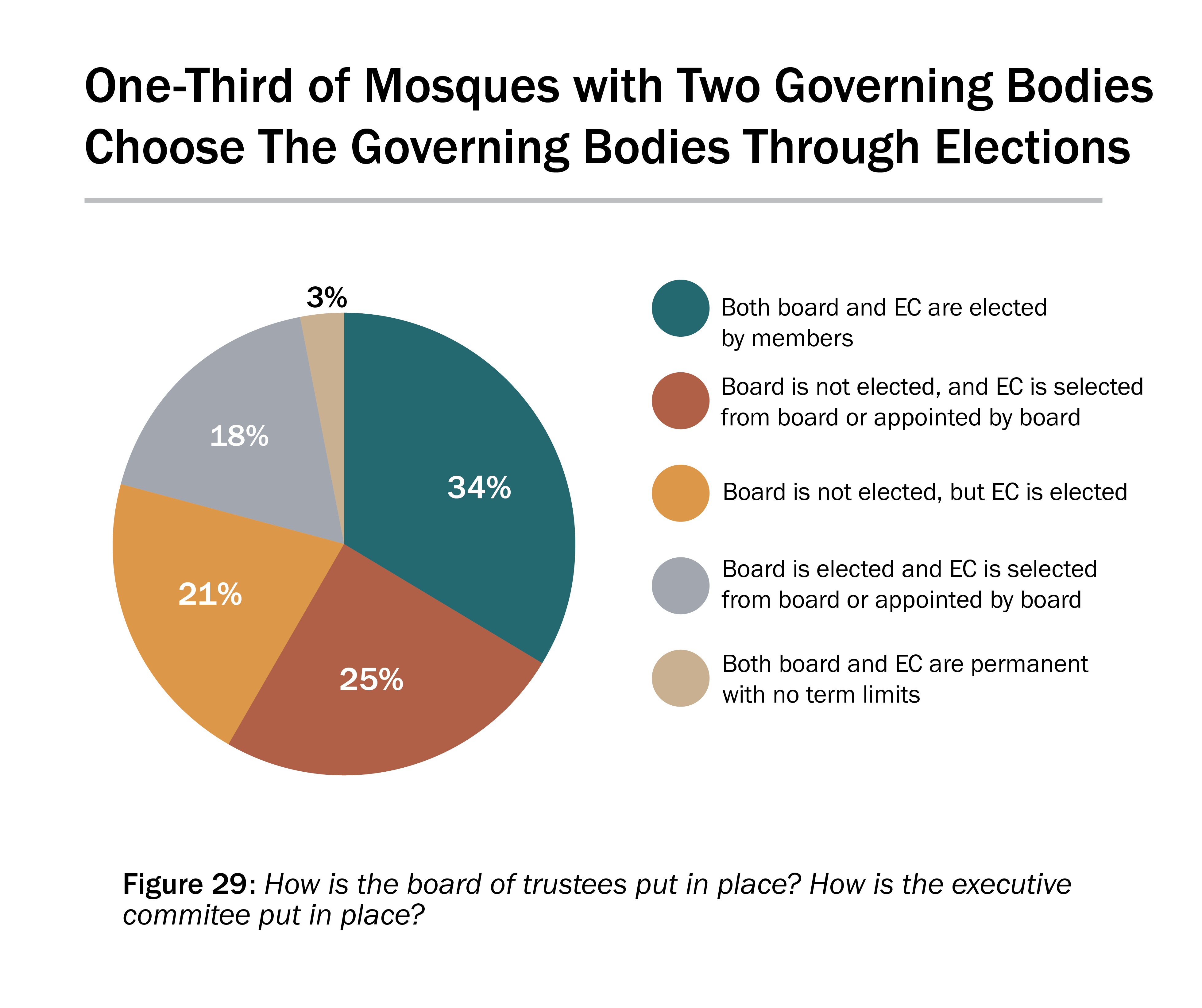

For mosques where there is both a board of trustees and an executive committee (sometimes called a board of directors), over one-third (34%) of these mosques have both bodies elected by the members of the mosque. In one-fourth of mosques (25%), the board of trustees is not elected (in almost all of these cases the board is permanent with no term limits) and the executive committee is selected from the board or appointed by the board. In this arrangement, the permanent board has all the power. In 21% of mosques with two governing bodies, the executive committee is elected but the board of trustees is not. In these cases, the executive committee usually has the greatest power, and the board serves more as holder of deeds and insurance against a takeover by hostile groups. In 18% of mosques with both a board and executive committee, the board is elected and the executive committee is selected from or appointed by the board. In this arrangement, the executive committee is powerful but easily reined in by the board.

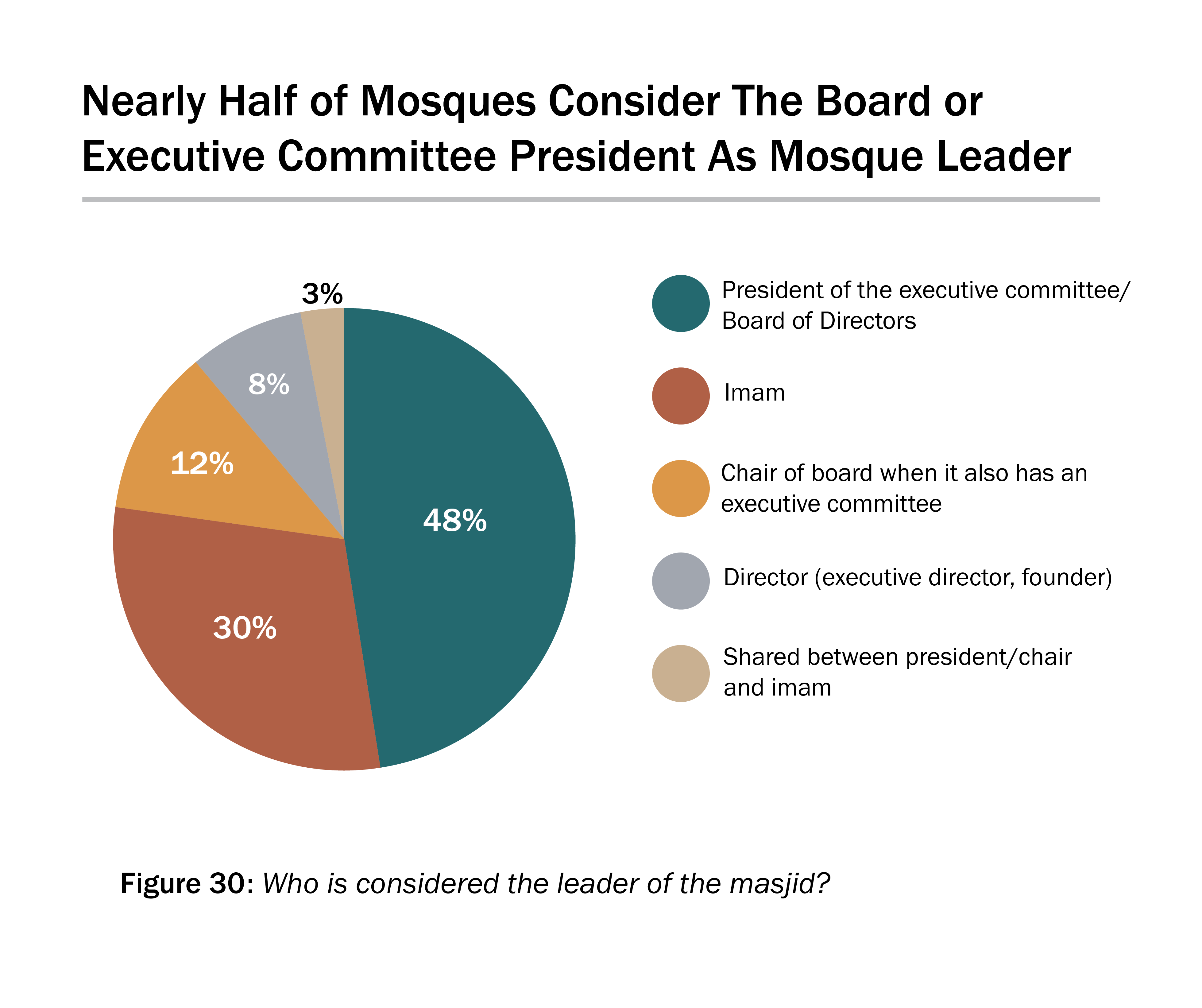

Who is the Mosque Leader?

The survey asked, “Who is considered the leader of the mosque?” Almost half of all mosques (48%) responded that the president of the executive committee/board of directors is considered the leader. When the executive committee along with the president is elected, the president is the leader in 74% of the cases. When the executive committee is selected or appointed, the president is the leader in 39% of the cases. It can be concluded that elections give a greater importance and legitimacy to the president.

The imam is the leader in 30% of all mosques. This is a sharp drop from 2010 when 54% of mosques had the imam as leader.

The reasons for this sharp decrease might include the decrease in the number of African American mosques which, in almost all cases, has the imam as the leader. However, even among non-African American (immigrant) mosques, there was a significant decrease. In 2010, 46% of immigrant mosques reported that the imam was the leader, but in 2020, only 22% responded that the imam was the leader. The imam is clearly losing authority to the president and other lay leaders.

Who is the Final Decision-Maker in the Mosque?

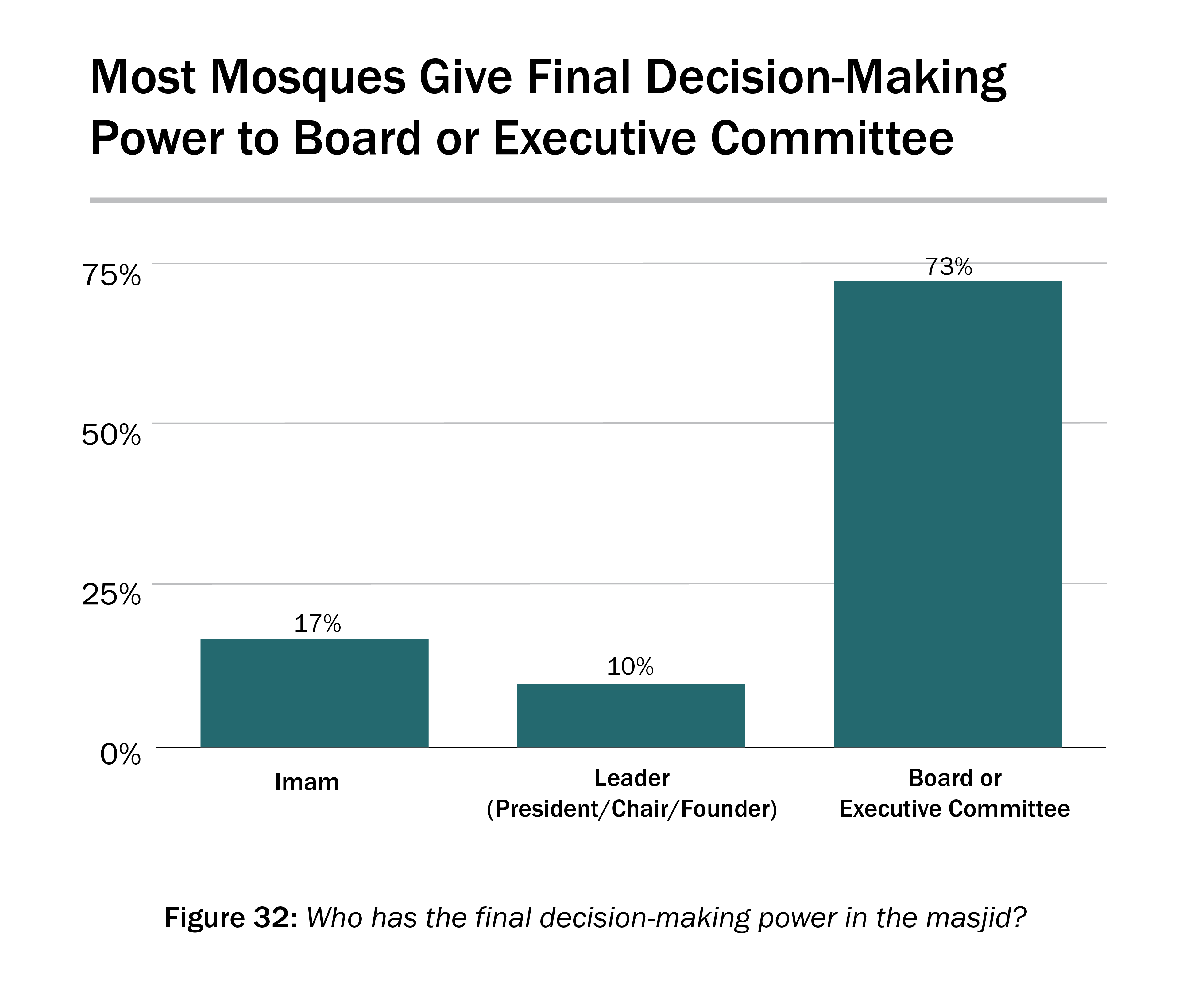

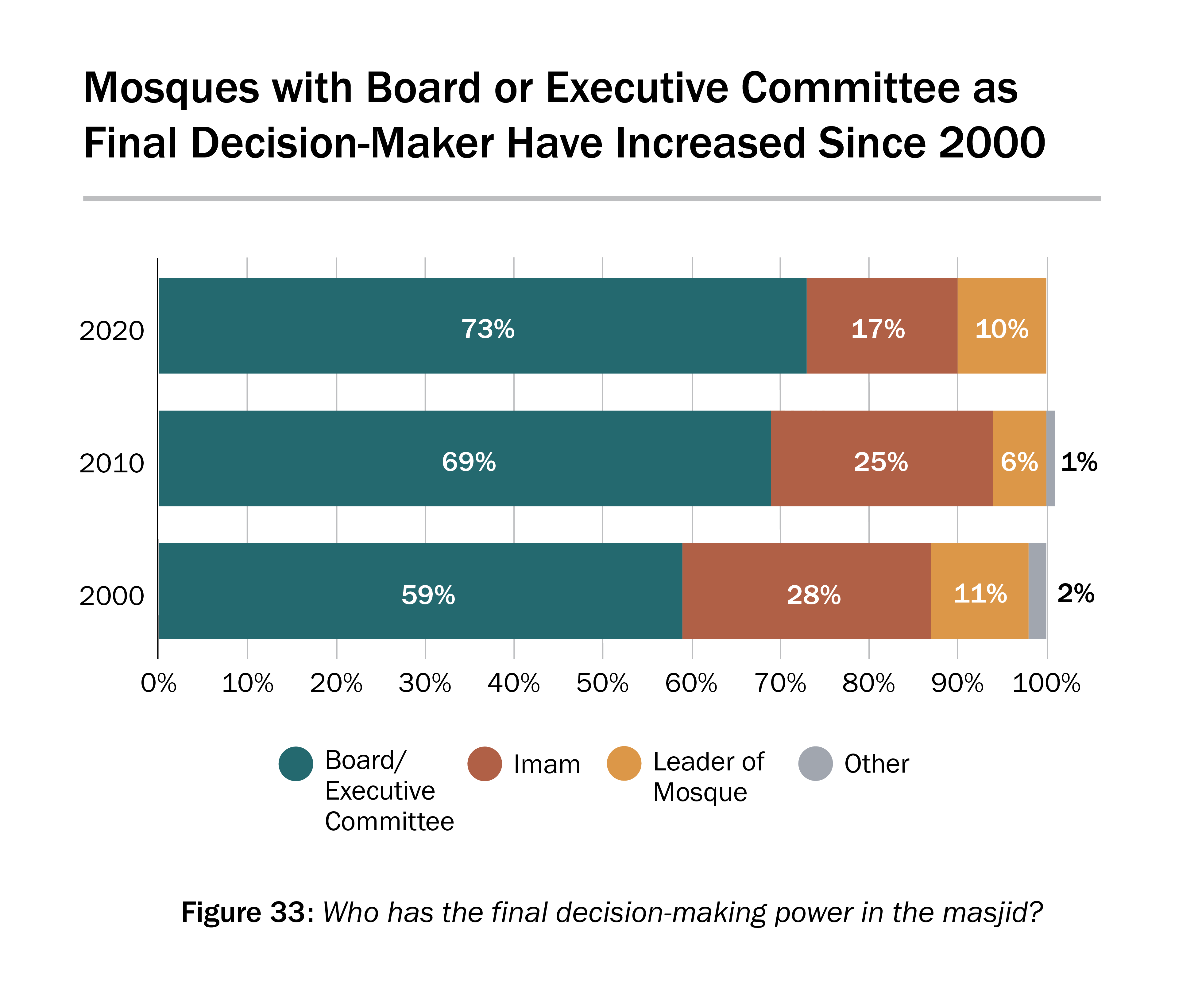

The Mosque Survey asked, “Who is the final decision-maker in the mosque?” Almost three-fours (73%) of all mosques answered that the board or executive committee is the final decision-maker.

There is a clear trend toward empowering the board/executive committee as the final decision-maker. In 2000, 59% of mosques answered that the board/executive committee was the final decision-maker, and in 2020 that figure was up to 73%.

Relationship Between Board/Executive Committee and Imam

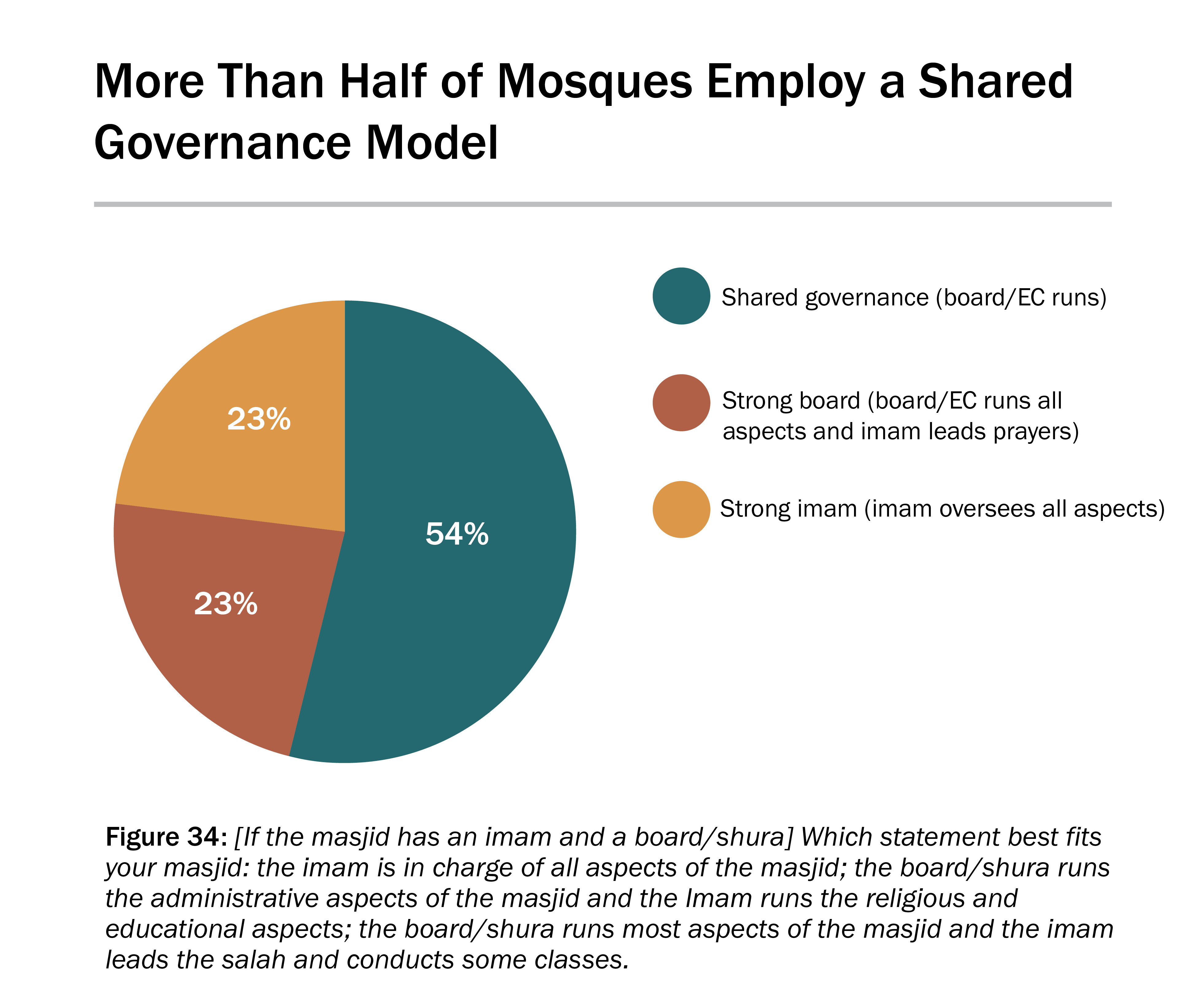

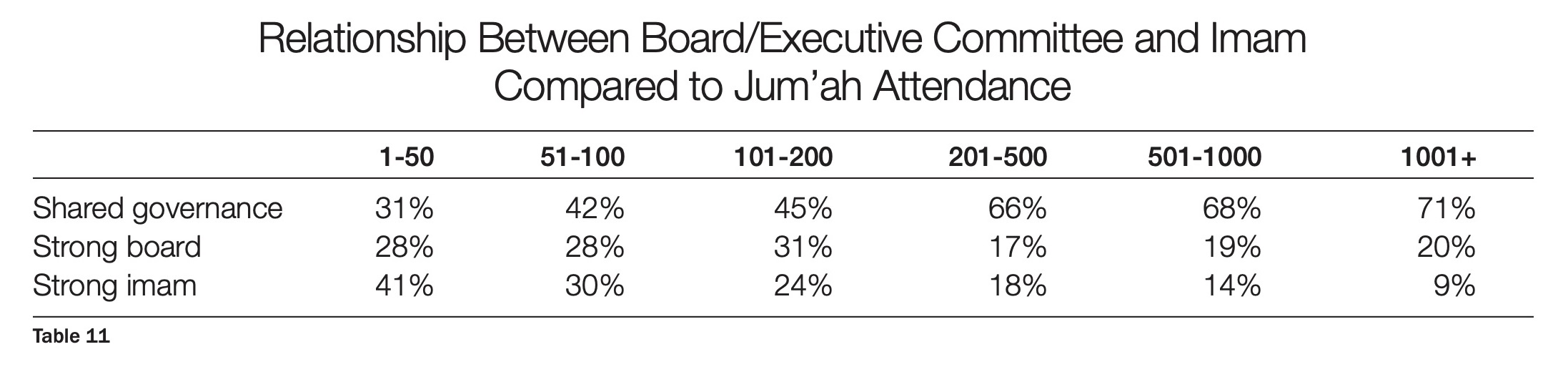

While mosque boards/executive committees and presidents are the dominant figures in most mosques, the open question remains as to the relationship between the board/executive committee and the imam. The Mosque Survey asked a question to explore this aspect. The question gives three options: (1) the board/executive committee runs the mosque and the imam runs the religious aspects of the mosque, and therefore he is the religious authority in the mosque. This option proposes a shared responsibility in the functioning of the mosque. The imam has his space to administrate affairs as he pleases, and the board/executive committee has their own managerial responsibilities. This option is called the shared governance option. (2) The second option is that the board/executive committee runs all aspects of the mosque, and the imam has a very limited role to lead prayer. Here the imam has little authority. This option is called the strong board. (3) The third option is where the imam runs all aspects of the mosque. In this regard he is the religious authority and at the same time the chief executive officer. This option is called the strong imam.

The majority of mosques (54%) follow the shared governance model. The remaining mosques are divided evenly between having a strong board or a strong imam. Almost all African American mosques adopt the strong imam model.

Over the decades, the shared model is increasing, and the strong imam model is decreasing.

In the mosque with shared governance between the board/executive committee and imam, 54% of them have the president as the leader of the mosque. The imam is the leader in only 20% of these mosques. In 2010, in the mosques with shared governance, the president was the leader in only 20% of mosques while the imam was the leader in 71%. Again, we see a sharp decline in the authority of the imam.

The increase in the shared model is associated with the increase in mosque size. The larger the Jum’ah attendance, the greater likelihood of the shared model. The strong imam model works in smaller mosques but not in larger mosques. The strong board model exists in roughly equal numbers in all mosques.

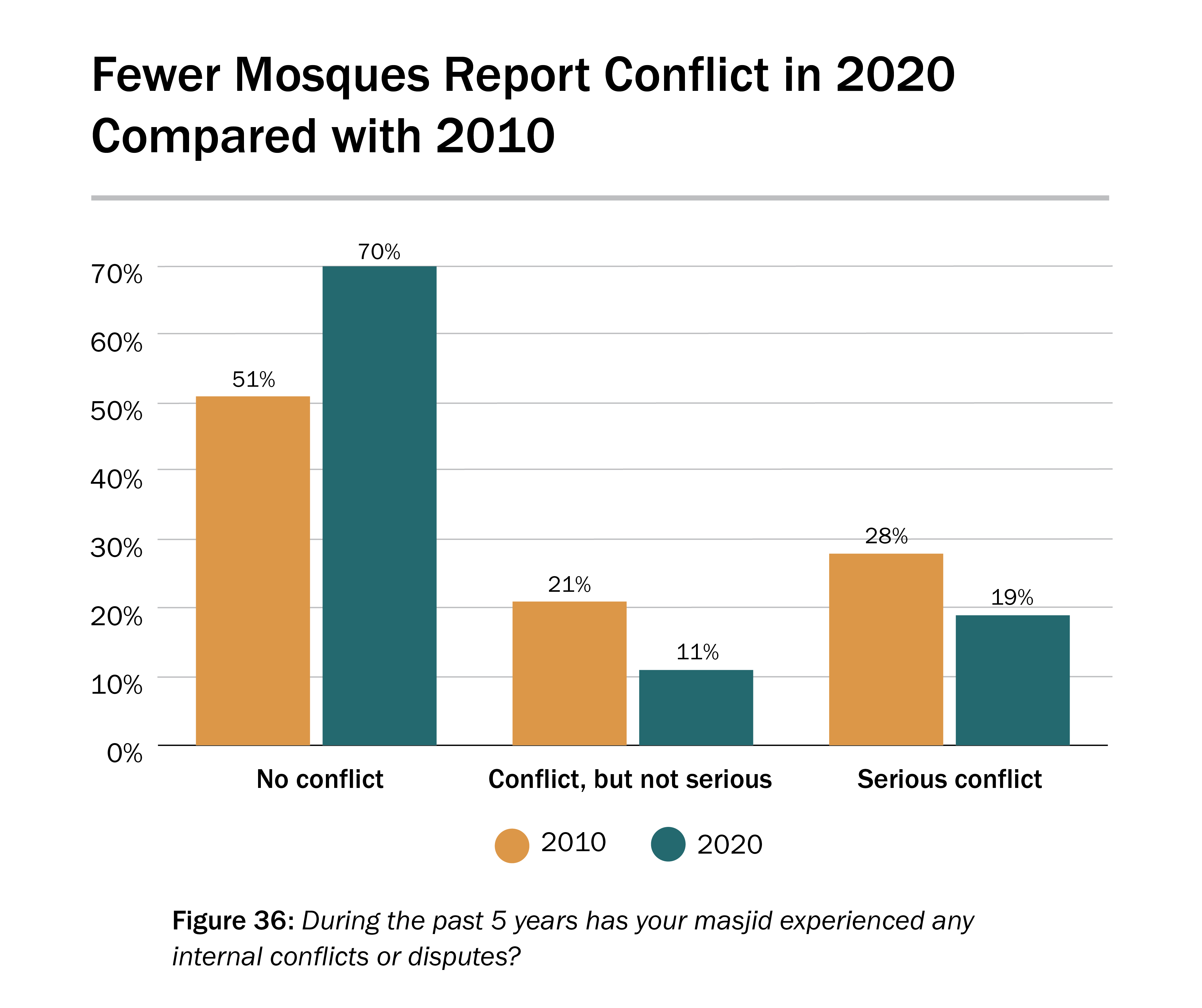

Mosque Conflict

The Mosque Survey asked if the mosque experienced any conflicts in the past five years. A large percentage (70%) of mosques answered that they had not experienced any conflict. Only 19% of the mosques stated that they had experienced a serious conflict. These figures are a dramatic change from 2010 when 51% of mosques stated that they had not had any conflict, and 28% said that they had experienced a serious conflict. It is difficult to explain this dramatic change. Are mosques better able to manage disagreements? Does the increase in the number of mosques mean that mosques are more homogeneous and, therefore, less prone to conflicts?

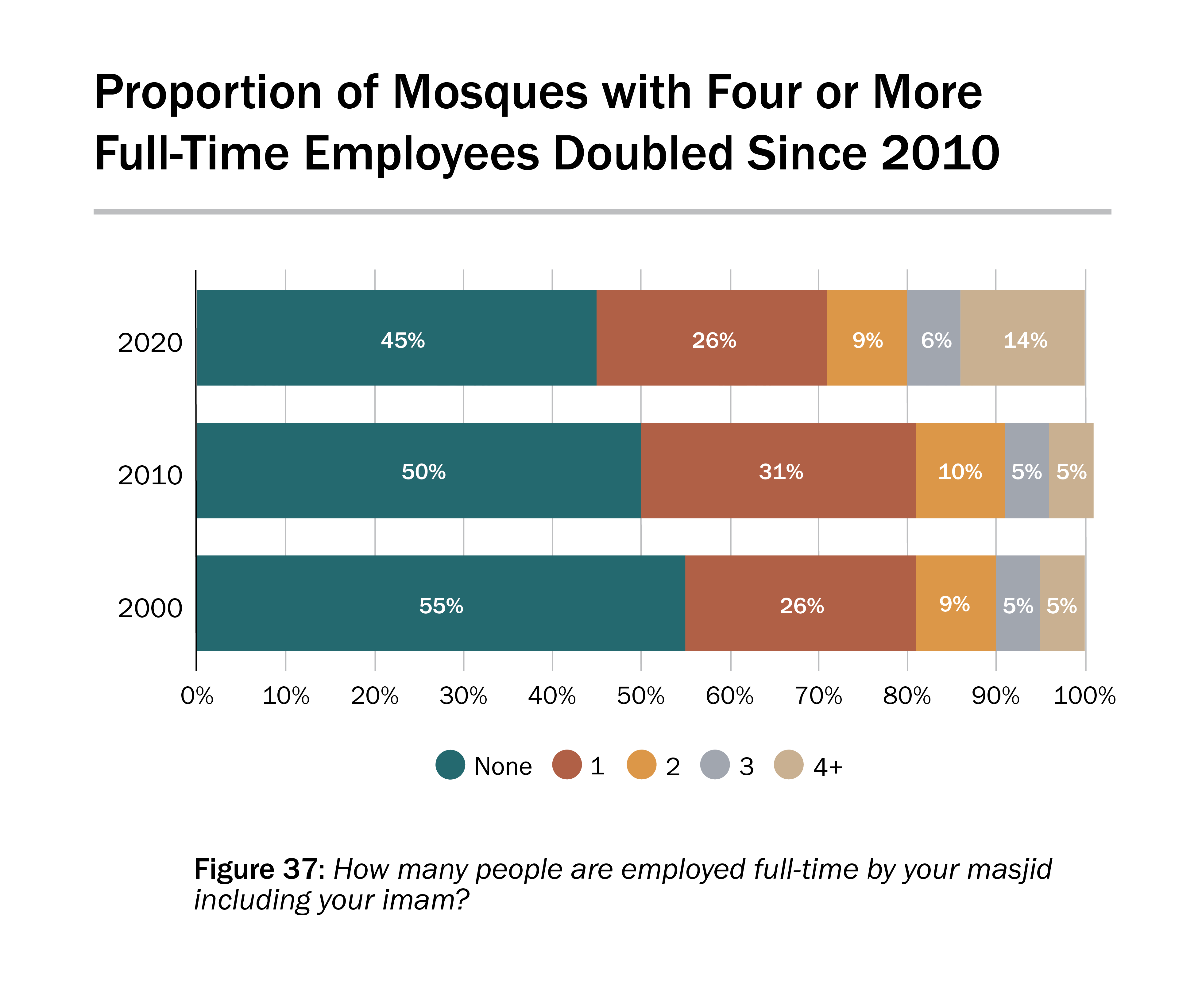

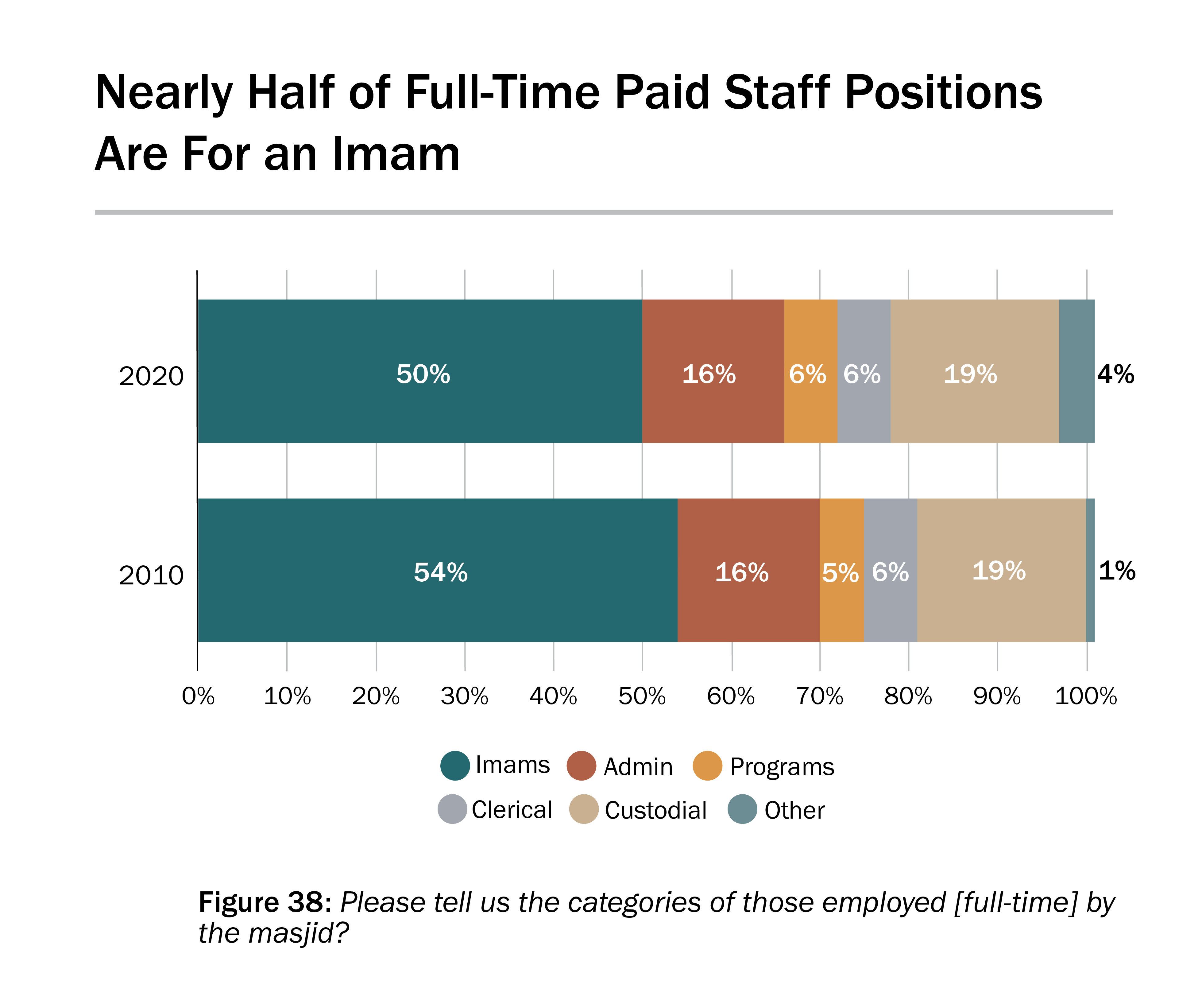

Mosque Staff

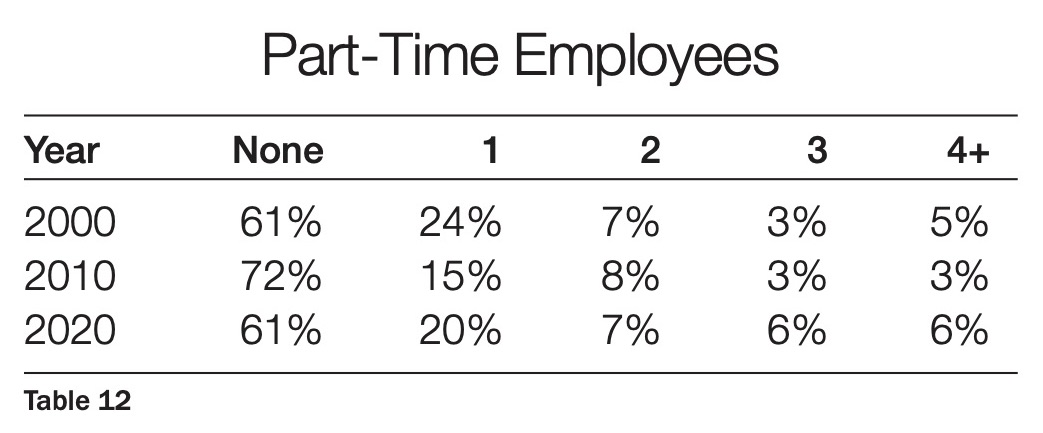

Over half (55%) of all mosques have at least one full-time staff, and 45% have no staff. The most significant increase is in the number of mosques that have four or more full-time employees. In 2000 and 2010, only 5% of mosques had four or more full-time employees, and in 2020 that figure is 14%. Although this marks an improvement over the decades, the fact remains that American mosques are severely understaffed.

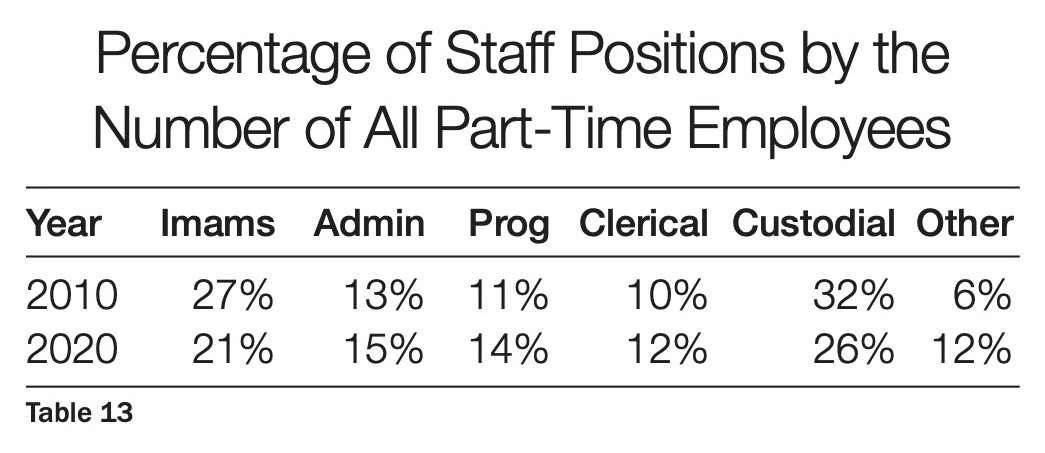

In terms of the type of full-time employees that a mosque hires, there is little change over the decades. Most hires are for an imam.

One of the types of full-time employees that the survey wanted to track is the number of youth directors because many mosque leaders voice the opinion that youth are a priority. In 2020, only 6% of mosques have a full-time youth director, indicating that priorities have not translated into reality.

Approximately 39% of all mosques have at least one part-time staff, which is a moderate increase from 2010.

The types of part-time employees did not change much. However, there are fewer part-time imams and more “Other Employees” which, in most cases, are security people.

Mosque Income

The average budget of mosques (not including full-time Islamic schools or zakah) in 2020 was $276,500, and the median budget was $80,000. This is a sizable increase from 2010.

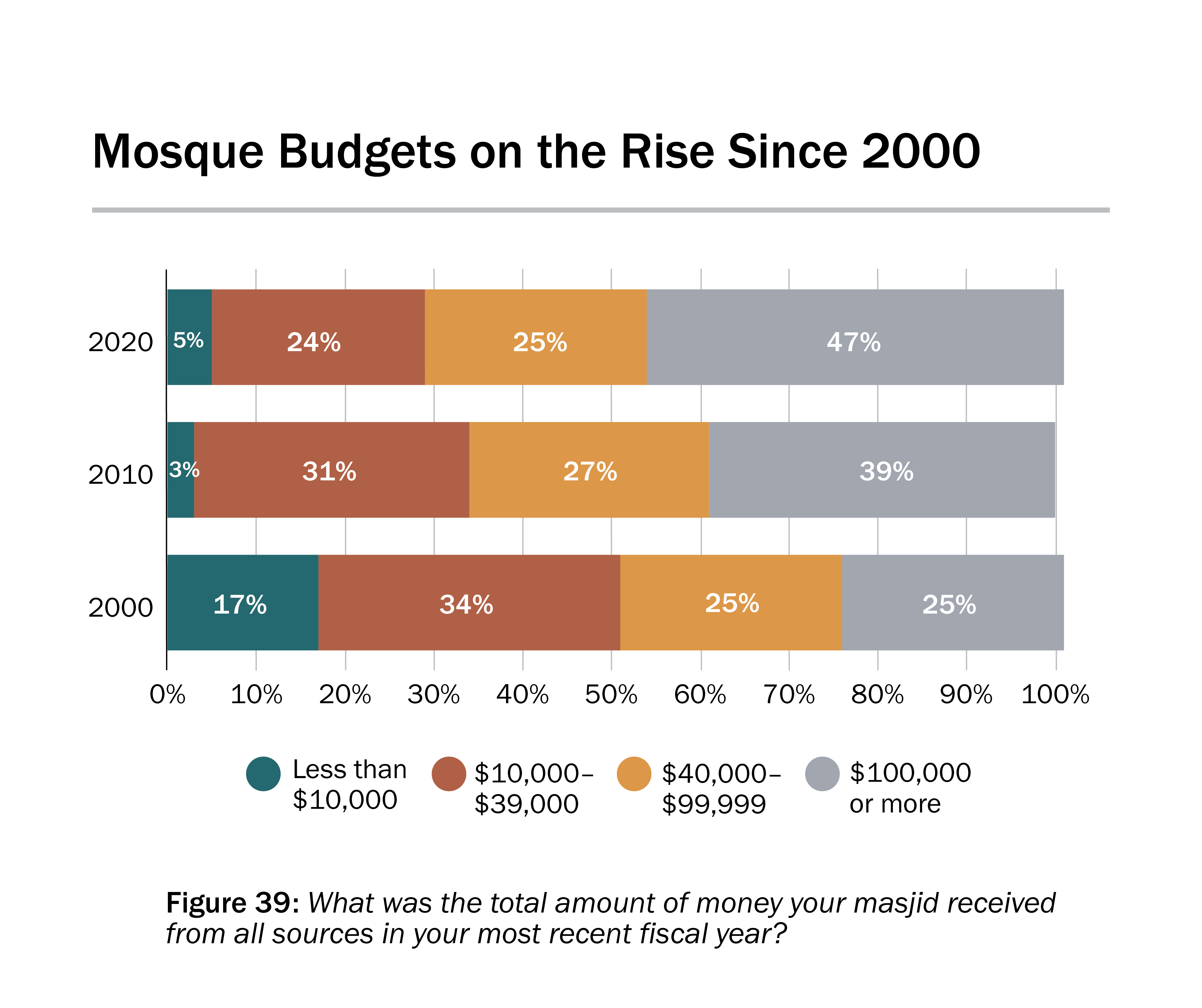

Mosques with budgets over $100,000 have steadily increased over the decades. In 2020, almost half of mosques (47%) have a budget over $100,000; in 2000, that figure was 25%; and in 2010 it was 39%.

Mosques typically keep separate accounts for money collected for zakah. Zakah is the required charity that Muslims must pay if their savings exceed a certain amount. These charitable funds are to be distributed to poor and needy people. This is the first time that the Mosque Survey asked about zakah. In 2020, mosques collected on average $40,640 for zakah. The median amount is $15,000.

Adding together budget and zakah, the average amount of money collected by mosques is $317,140, with zakah comprising 13%.

Mosque and church incomes are roughly the same, but churches achieve their income levels with far fewer people. Churches average $311,782 with 180 regular participants. Mosque income averages $317,140 with an average Jum’ah attendance of 410. Dividing income by participants, church participants give $1732 per year, and mosque participants give $674 per year. More study is needed to understand this disparity.

Methods of Fundraising

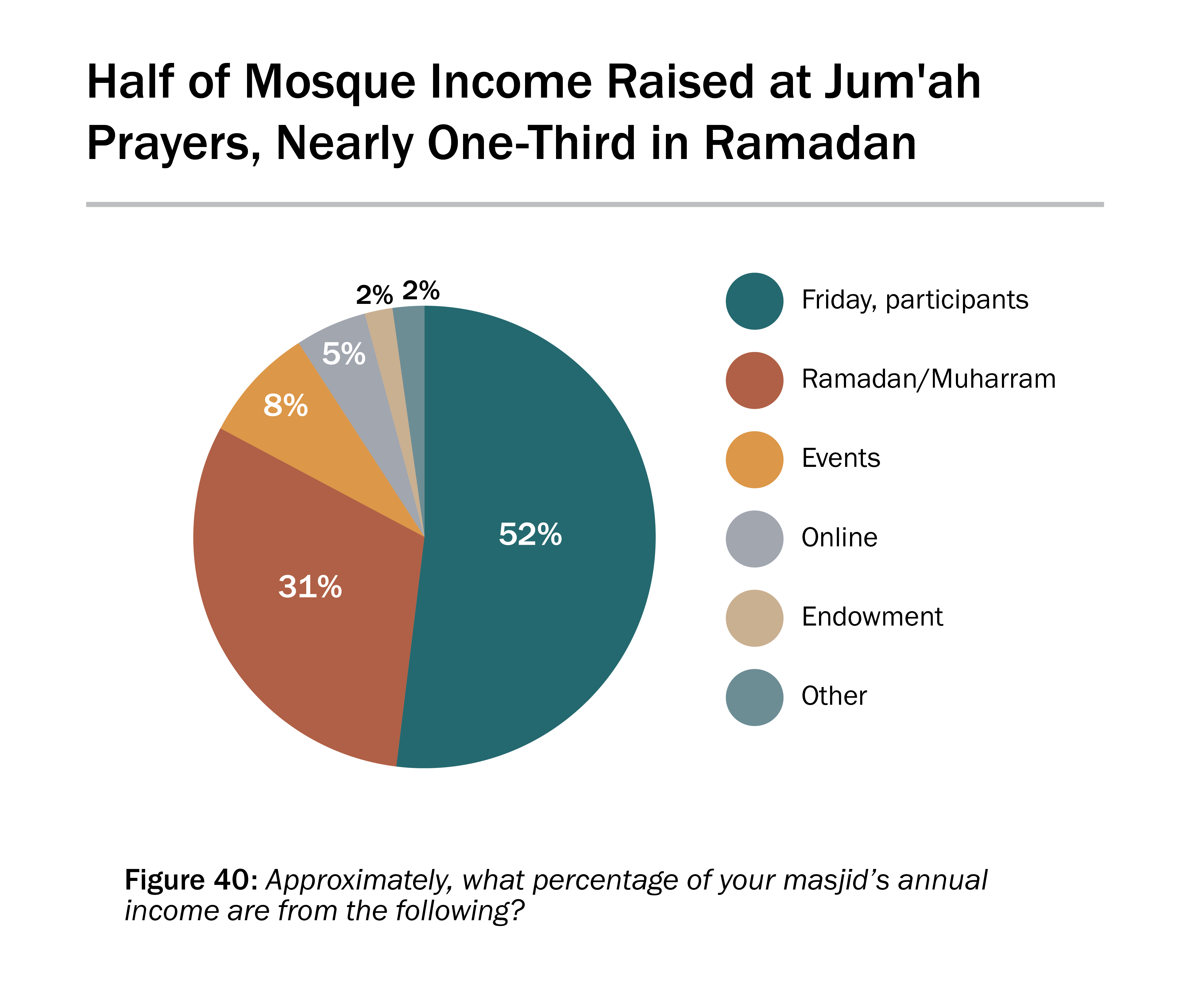

A new question in the 2020 Mosque Survey explored the various ways that mosques raise money. There are six categories. (1) The first category is Friday collection and other ways that participants give, such as membership fees and pledges. (2) The second category was fundraising activities during Ramadan or for Shi’ites fundraising during Muharram. (3) The third category was fundraising events such as a banquet. (4) The next category was online giving which includes automatic withdrawals and donations from the website. (5) The fifth category was income from endowments, investments, and rentals, including the rental of mosque facilities and/or property owned by the mosque. (6) The last category was “other,” where some responses included the sale of lunches/dinners.

The results show that the majority (52%) of income for mosques comes from Friday collections and pledges. A significant portion of income comes from the months of Ramadan or Muharram. Very little income comes from other sources.

The only outliers are African American mosques where they do little fundraising during Ramadan and focus more on Friday collections. While immigrant mosques raise 34% of their income from Ramadan/Muharram, African American mosques only raise 12%. African American mosques receive 72% of their income from Friday congregational services, while immigrant mosques receive 49%.

.

Shi’ite Mosques: Basic Characteristics

The results of the US Mosque Survey as detailed in reports 1 and 2 include both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques. However, it was thought appropriate to have a separate section for Shi’ite mosques to reveal similarities and differences with Sunni mosques.

Overall, Shi’ite mosques are very similar to Sunni mosques in almost all aspects. However, Shi’ite mosques tend to be smaller and younger than Sunni mosques.

Number and Location of Shi’ite Mosques

In the total mosque count for the 2020 US Mosque Survey, we identified 6.5% of the mosques as Shi’ite. In the comprehensive Mosque Survey, which is a sampled survey, 6% of the mosques self-identified as Shi’ite. The closeness of the two percentages elicits some confidence that the results of the comprehensive Mosque Survey should be representative of Shi’ite mosques. However, the small sample size should cause some caution in drawing conclusions.

In 2010, the percentage of Shi’ite mosques in the comprehensive Mosque Survey was 7%, which means there were 126 Shi’ite mosques. In 2020, the 6% of Shi’ite mosques equals a total of 166 mosques. Therefore, Shi’ite mosques increased in number from 126 to 166, which is a 32% increase. This matches almost exactly the increase of 31% for all mosques from 2010 to 2020.

Shi’ite mosques are spread out over the American landscape in virtually the same pattern as Sunni mosques. However, there was a significant increase of Shi’ite mosques in the South: in 2010, 20% of Shi’ite mosques were located in the South; that figure is now 37%.

In terms of the urban-suburban dynamic, Shi’ite mosques have almost the same distribution. However, slightly more Shi’ite mosques are located in older residential areas of large cities as opposed to Sunni mosques; and fewer Shi’ite mosques are in the suburbs than Sunni mosques. One possible explanation for this is that the Shi’ite community is younger than the Sunni community and, therefore, slightly behind the cycle of the immigrant move to the suburbs.

Founding Age of Shi’ite Mosques and Mosque Structures

The youth of Shi’ite mosques is confirmed by the dates of their founding. While 57% of Sunni mosques were established before 2000, only 39% of Shi’ite mosques were founded before 2000. A remarkable 35% of Shi’ite mosques were founded in the decade of 2010, as compared to 18% of Sunni mosques.

The youth of Shi’ite mosques is also seen in the low percentage of purpose-built Shi’ite mosques. Only 19% of Shi’ite mosques were built as mosques, as compared to 38% of Sunni mosques. Undoubtedly, as the Shi’ite community grows it will follow the pattern of constructing mosques.

Mosque Size

The average size of Shi’ite mosques is significantly smaller than Sunni mosques. While Sunni mosques average approximately 1,500 total participants (median is 225), Shi’ite mosques average 500 participants (median 225). To arrive at these figures, Sunni mosques were asked about their Eid prayers and Shi’ite mosques were asked about their Muharram celebrations. The difference in Jum’ah attendance is even greater, because in part some Shi’ite mosques do not emphasize Jum’ah prayer. The average Jum’ah size in Shi’ite mosques is 91 (median is 50), and in Sunni mosques the average is 429 (median 200).

Nevertheless, Shi’ite mosques are growing in Jum’ah attendance at approximately the same rate as Sunni mosques. Among Shi’ite mosques, 61% have grown in Jum’ah attendance by 10% or more, compared to 72% for Sunni mosques.

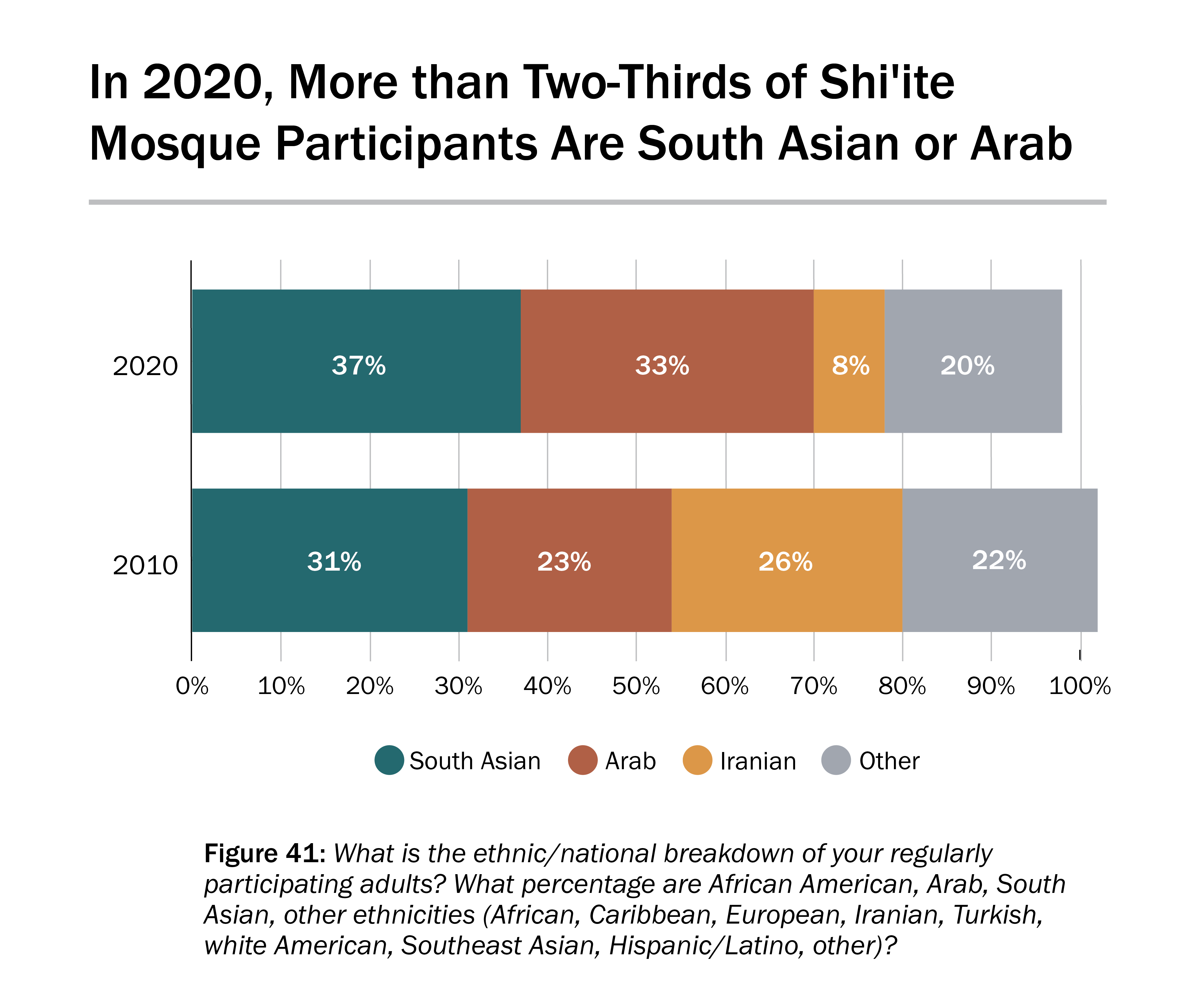

Ethnicity/Nationality in Shi’ite Mosques

Arabs and South Asians dominate Shi’ite mosques. Among all attendees at Shi’ite mosques, 45% of mosque participants are Arab and 38% are South Asian. The percentage of Arab attendees is growing significantly: in 2010, the percentage of Arab participants in Shi’ite mosques was 32%; now, it is 45%.

In terms of the dominant ethnic/national group that attends the mosque, Arabs and South Asians again dominate in Shi’ite mosques.

The major change from 2010 to 2020 is the dramatic decrease in mosques that are dominated by Iranians: in 2010, 26% of Shi’ite mosques were dominated by attendees from Iran, and in 2020 that figure is down to 8%. Is this an anomaly due to a small sample size, where a survey can miss a small population? Iranians, however, are present in Shi’ite mosques: 60% of Shi’ite mosques have some Iranians that attend. Possibly the mosques in 2010, which were dominated by Iranians, have now gained new attendees from other countries.

Imams and Governance

Only 44% of Shi’ite mosques have a full-time paid imam which is close to the Sunni percentage of 50% who have a full-time paid imam. Thus, both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques are handicapped by the absence of full-time paid imams. Of the Shi’ite full-time paid imams, none were born in the US: 62% of them came from Arab countries, 31% from South Asia, and 8% from Iran. Half of the full-time paid imams received their Islamic degrees from Iran, and the other half received their degrees from Iraq.

The governance structures of Shi’ite mosques are the same as in Sunni mosques. Little difference seems to exist in the organizational dynamics of Shi’ite and Sunni mosques.

.

Sources

Besheer Mohamed, New Estimates Show U.S. Muslim Population Continues to Grow (Pew Research Center), January 3, 2018.

Faith Communities Today, 2015 National Survey of Congregations.

Dalia Mogahed and Erum Ikramullah, American Muslim Poll 2020: Amid Pandemic and Protest (Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2020).

Barna Group, The Aging of America’s Pastors, March 1, 2017.

Thomas Rainer, Six Surprises About Church Staff Salaries and Budgets, November 7, 2016.