A New Way Forward: Strengthening the Protection Landscape in Mexico

Summary

Mexico plays a unique role in North America as a sending, transit, destination, and return country for many migrants, including asylum seekers and other forcibly displaced people. In recent years, Mexico has increasingly become a destination for asylum seekers. The Mexican asylum system has improved, but for many seeking asylum in Mexico, gaining access to a fair and timely process is still not a guarantee. Mexico’s asylum system is generous on paper, but in practice it faces several challenges that undermine its effectiveness. Coupled with these issues is increased pressure from the United States to adopt an enforcement-centered approach to managing migration flows. But as more people turn to Mexico to seek international protection, it is increasingly important for Mexico to provide a more holistic and human-rights-centered approach to migration management, and in particular to focus its attention on improving its international protection system. Strengthening the protection system would serve the dual purpose of providing a more fair and transparent process for asylum seekers and enabling Mexico to better manage the increasing number of asylum applications it receives. This is particularly important as migration from Central America and other regions is likely to be the norm for years to come, and trends indicate asylum claims in Mexico will only increase.

Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM) and the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) are the two Mexican institutions with key responsibilities for asylum seekers and other migrants. The INM is the authority in charge of regulating the entry, stay, and exit of foreign and Mexican citizens in Mexico, and the COMAR is responsible for processing refugee status recognition applications. Both INM and COMAR can mitigate current and future problems by promptly implementing several improvements that could have lasting impacts. By implementing these fixes, the INM would improve access to asylum for migrants in detention and at airports and improve the issuance of key documents. If implemented, the recommendations we make would also enable COMAR to reduce its backlog and provide better screenings for asylum seekers. Asylum seekers would enjoy improved ability to exercise their economic, social, and cultural rights during their wait for their claims to be resolved. We also offer recommendations designed to enable the UN Refugee Agency (UNCHR) to better meet the goal of assisting the Mexican government through the Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework (known as MIRPS by its Spanish acronym), and to enable the United States to be a more effective regional partner as Mexico seeks to provide more effective migration management.

Background

Mexico’s international protection system is generous on paper. Mexico is party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the Mexican Constitution guarantees the right of people to seek and receive asylum. Mexico also among the governments that adopted the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, which broadened the grounds for asylum. Mexico’s 2011 Law of Refugees, Political Asylum, and Complementary Protection provides protection to asylum seekers who meet the requirements of the 1951 Convention or the Cartagena Declaration. In practice, Mexico applies these standards to asylum seekers from certain countries, especially Venezuelans, 98 percent of whom are granted protection. Asylum seekers who are granted refugee status through the COMAR become permanent residents with the right to stay indefinitely, access to employment, healthcare, and education. They can apply for naturalization after four years. If the asylum seeker is not granted refugee status, the person may be granted Complementary Protection due to risk of torture, cruel or inhumane treatment. Complementary Protection provides access to many of the same rights that refugee status entails, save for family reunification.

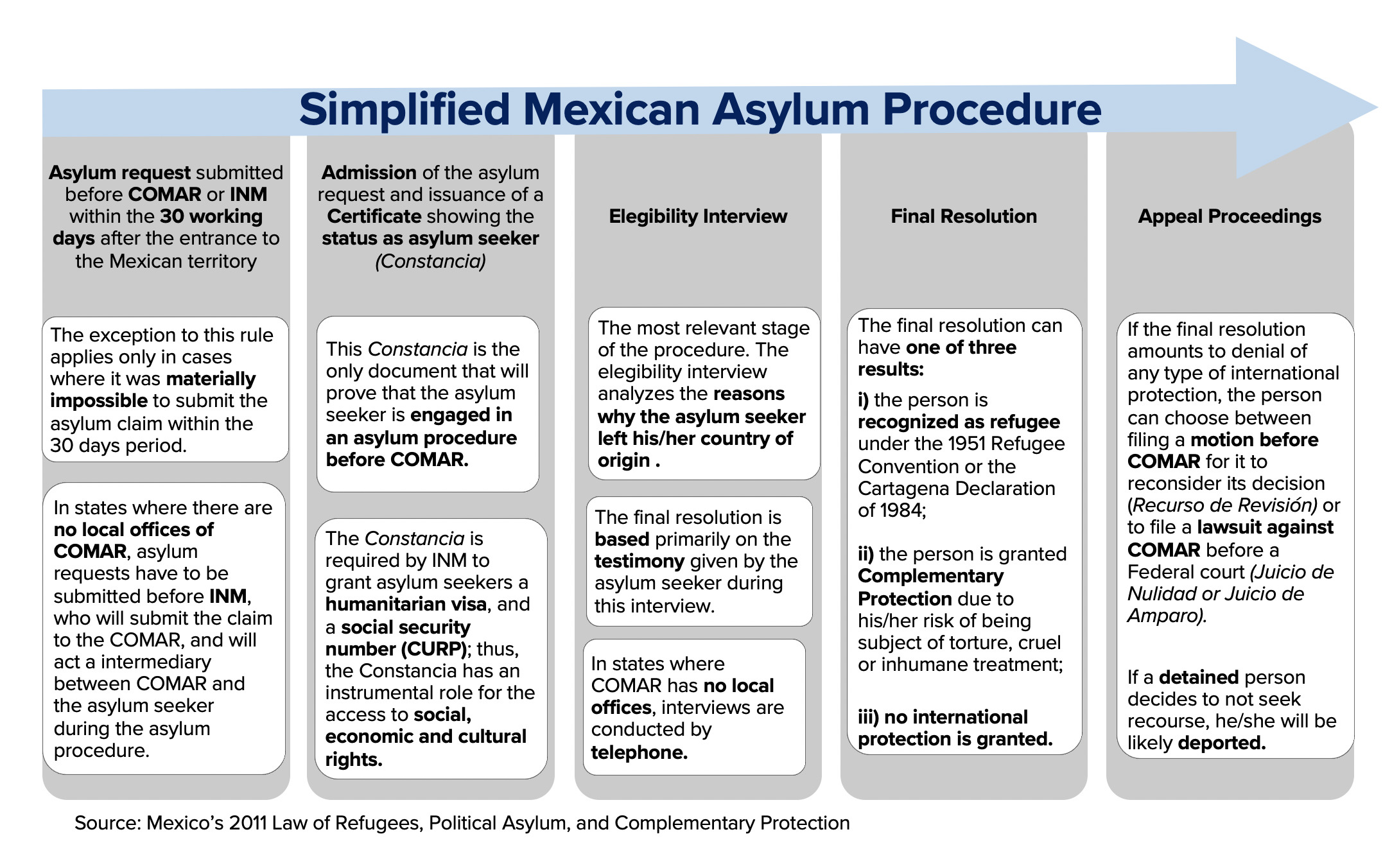

The asylum process is composed of four to five key stages, outlined below:

Yet, this system has serious problems that undermine its generosity and effectiveness—challenges that are exacerbated by the severe lack of funding for COMAR. For years, COMAR suffered from a woefully low budget that contributed to a mounting backlog of unresolved claims. Thankfully, from 2019 to 2020, the Mexican government increased COMAR’s budget from 20,843,364 Mexican pesos (roughly $1,010,175 USD) to 47,360,858 pesos (roughly $2,295,348 USD)—an increase of 127.7 percent. However, the budget for 2021 decreased by 14.3 percent, despite the overwhelming need to increase funding. Coupled with a reduced budget is a growing xenophobia in Mexico, particularly in northern states where the U.S.-imposed Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) have exacerbated tensions. Even the INM chief is on record making xenophobic comments against migrants. These sentiments influence the political will of the Mexican government to enact reforms.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) supports the COMAR’s work, largely through the Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework (or MIRPS), a state-led regional application of the Global Compact on Refugees. In particular, the MIRPS is designed to strengthen protection, promote solutions for affected persons, and address the underlying causes of forced displacement by promoting a stable environment that ensures security, economic development, and prosperity. Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Panama constitute the members of the MIRPS, and they work together to strengthen protection and develop solutions for refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced people, and returnees with international protection needs. In Mexico, the MIRPS action plan calls to improve the procedure for the applications for asylum, including the registration phase, attention to specific needs, and the refugee status determination.

It is important to note that Mexico’s policy decisions around its migration and international protection systems do not exist in a vacuum; the United States exerts a great deal of pressure and influence on the direction of Mexico’s policy choices. In 2019, the United States threatened to impose 5 percent tariffs on all Mexican imports if the Mexican government did not increase its northern border enforcement efforts. Following these threats, the United States and Mexico signed a migration deal that would drastically alter the course of Mexico’s migration enforcement. The Mexican government deployed thousands of National Guard members to its northern and southern borders. Since the deployment of the National Guard, the number of detained migrants has increased substantially. The following month after the United States and Mexico signed the agreement, the INM held over 30,000 migrants in detention, which is the highest number of detentions made in a month in the last 13 years.

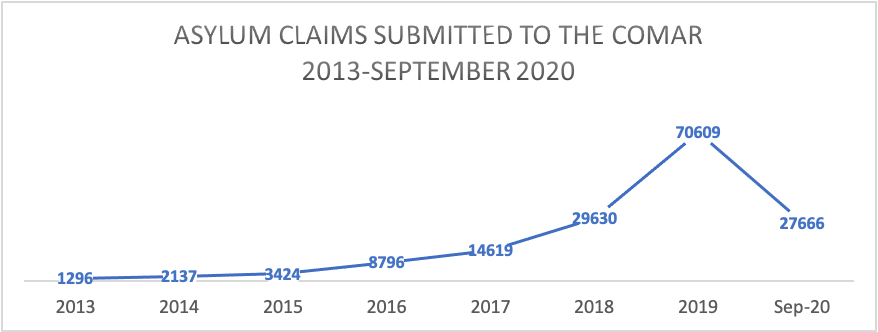

The increased enforcement in Mexico has been accompanied by a set of interlocking policies enacted by the United States government to virtually end asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. Taken together, these factors have resulted in a sharp increase in the number of people seeking asylum in Mexico. In particular, U.S. policies including “metering” and the so-called Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) along Mexico’s northern border push many asylum seekers who have had hopes to for asylum in the United States to apply in Mexico instead as they grow tired of long waits in unsafe conditions. In addition, others are applying for asylum in southern states of Mexico as a way to gain safe transit through the country in an increasingly enforcement-heavy environment. And while the number of asylum claims had grown every year between 2013 and 2019, claims rose far more sharply after the U.S.-Mexico migration deal and implementation of restrictive U.S. policies. According to official statistics, 80 percent of the more than 150,000 asylum requests received by COMAR between 2013 and 2020 had been filed within the last three years.

While U.S. actions may have accelerated the increase in asylum claims, other factors have also been at play. More people have been on the move than ever before. Furthermore, many asylum seekers now view Mexico as a viable place to seek asylum, and as conditions worsen in their home countries, Mexico can provide relative safety and prosperity. And although 2020 has seen a reduction of claims due to the pandemic, in 2019 the number reached its historic peak with more than 70,000 claims, which represents an increase of more than 5,000 percent of asylum requests submitted before COMAR since 2013.

This increase has placed a significant strain on Mexico’s protection system, particularly as funding, staffing, and institutional capacity for this system is inadequate to respond to such high numbers of claims. With a Biden administration starting in January of 2021, there may be new opportunities for both countries to work together on migration reform. Of course, the United Sates must change its current draconian asylum policies, but regardless of the election outcome and subsequent U.S. policies, it is Mexico’s best interest to strengthen its asylum system to respond to the increasing number of asylum claims, as people will continue to seek asylum under any circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also created challenges for asylum seekers looking to access international protection. Although the COMAR continued to accept asylum applications during the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on movement severely limited those with international protection concerns from accessing the Mexican asylum system because they could not travel. Now, a new challenge is on the horizon: as borders reopen, more people may seek to cross into Mexico in large numbers to seek asylum or safe transit through the country. Examples of this are already occurring: in September 2020, a caravan of thousands of people set out from San Pedro Sula with the intention of reaching the United States. Although the caravan was mostly halted in Guatemala, Mexican officials were eager to clamp down on the movement of people to and through the country—particularly considering U.S. pressure and the pandemic.

COMAR budget cuts, xenophobia, U.S. measures that have compounded Mexican migration challenges, and a likely increase in migration flows in the coming year all create formidable obstacles to progress. But none of these obstacles should stand in the way of a range of improvements that the Mexican government can implement to address the gaps in protection and provide a fair and humane asylum process that upholds the rights of the forcibly displaced.

Barriers to International Protection

Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM)

The INM handles enforcement, issues humanitarian visas, and performs a variety of other immigration functions. The INM has offices in all 32 states in Mexico and is in charge of receiving asylum requests from asylum seekers in states where the COMAR is not present. In recent years, the INM has come under fire for corruption allegations. In August of 2020, 1,040 INM agents were fired for coercing migrants to pay up to 300 pesos to process their immigration documents. The INM has also been criticized for prohibiting access for civil society organizations in migration stations. In general terms, the INM lacks an independent oversight mechanism to ensure transparency in the agency. Beyond these broad and large-scale problems, Refugees International has specific concerns related to INM practices on detentions and deportations, humanitarian visas, and protection from return.

Detentions and Deportations:

Migrants in Mexico who fled persecution and violence are often detained in migration stations and deported before they have the option to seek asylum. Not only are would-be asylum seekers detained and often rapidly deported, but reports note that many would-be asylum seekers are at high risk of detention. Asylum seekers who may be arbitrarily detained in the custody of the INM do not have the ability to question the legality of their detention before any other administrative or judicial authority.

Migrants who may qualify for asylum are often unaware they can seek asylum while in detention because INM staff may have failed to disclose this option to those detained. In some cases, INM officials have openly discouraged migrants from applying for asylum. Asylum seekers who are detained may grow tired of extended periods in detention and opt to be returned voluntarily to their home countries instead of completing the asylum process. Although detentions rates have reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic because the INM agreed to release migrants for public health reasons, stakeholders disclosed to Refugees International that those deportations that are taking place are occurring more rapidly than before the pandemic, leaving even less time and resources for migrants to apply for asylum.

Visitor Card for Humanitarian Reasons:

Migrants with a high risk of vulnerability, such as asylum seekers, stateless people, or those who flee because of public-interest or force majeure reasons, are entitled by law to request a “humanitarian visa,” whether at a Mexican point of entry or inside Mexican territory. This legal document is viable for six months to one year, and it can be renewed if the reason for its issuance persists beyond its expiration date. The humanitarian visa contains a social security number called CURP, for its acronym in Spanish, which facilitates the access to education, public health services, and a formal job in Mexico. Thus, the humanitarian visa has pivotal role in the access of asylum seekers to social, economic, and cultural rights.

Yet, individuals who enter Mexico for the reasons previously mentioned are less likely to receive a humanitarian visa at the border when travelling individually, than those who enter in large groups. In this respect, there are no approval rates, nor official figures of the total of requests of humanitarian visas submitted at the border. However, considering the large amount of Central American people crossing into Mexico and the reasons they flee their countries of origin, it would be expected to find higher figures of humanitarian visas granted at a point of entry. Nonetheless, between 2015 and September 2020 only 0.06 percent of the total registered entries into Mexico were for humanitarian reasons. Although there has been a notable increase of registered entries for humanitarian reasons since 2019, data suggests this increase is due to the entrance of migrant caravans and Mexican immigration policies to address them. In fact, an alarmingly low number of humanitarian visas were granted at an entry point in the years where there were not large caravans, suggesting that access to a humanitarian visa at the border is more likely to be guaranteed in contexts of large, collective entries like in the case of caravans. Although the issuance of humanitarian visas in these cases can be regarded as a protective measure since the humanitarian visa facilitates access to government services, migrants with a lower profile face more obstacles when accessing the humanitarian visa at a point of entry, which could also indicate legal and practical barriers in its access, and a lack of protection policies for vulnerable but less prominent migrants.

Furthermore, not all asylum seekers are issued a humanitarian visa. According to Article 52 Section V of the Mexican Immigration Law, asylum seekers engaged in an asylum procedure are entitled to request a humanitarian visa. Although there is no official data on the total of requests for a humanitarian visa made by asylum seekers, it calls our attention that the total of humanitarian visas granted between 2015 and September 2020 represents 55 percent of the total of asylum requests submitted in the same period. The disparity between the humanitarian visas issued and the asylum claims submitted before COMAR certainly would suggest that thousands of asylum seekers have not had access to the humanitarian visa.

Finally, through interviews with international and local NGO’s, Refugees International found that detained asylum seekers are not granted this visa upon release from detention. In these cases, along with the exit permit that allows them to leave the detention center, INM grants them another type of legal permit that is not in accordance with the Mexican Immigration Law, and has significantly fewer benefits than the humanitarian visa, such as its short duration (45 days), and its format (a piece of paper rather than a formal card).

Protection from Return:

For migrants who arrive by air, the INM operates a migration station within the Mexico City airport commonly referred to as “La Burbuja.” If the INM identifies inconsistencies in an individual’s paperwork, an INM official will conduct an interview with the migrant to determine if the person is allowed to enter Mexico or be issued a “rechazo”—a rejection, which results in return to their country of departure or to another country where the person would be admitted. A rechazo is different from a deportation, since the latter implies entry of the person into Mexican territory, whereas with a rechazo the person is not considered to have entered Mexico. According to the Regulations of the Airports Law, the access to these spaces is restricted, and only authorities and airline officers are allowed to enter. Therefore, oversight of the INM functions in this space is difficult to achieve. As a result, the INM does not need to provide good cause or justification for this interview, which raises concerns about discrimination and arbitrariness. Unless the individual has a network in Mexico that can contest the rechazo, migrants are often rapidly returned before having the chance to apply for asylum. In cases where an individual wishes to apply for asylum but is scheduled to be returned, a judge can issue a halt to this return under Mexico’s protection law, the Ley de Amparo. Although a judge can halt this return, there is no immediate notification system communicating the judge’s ruling to INM officials in the airport. A court representative must physically go to the airport to deliver the paperwork. Lawyers told Refugees International that, in some cases, migrants have been returned before the court representative could deliver the paperwork.

Comisión Mexicana para la Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR)

The COMAR is the agency responsible for resolving asylum claims and determining refugee status. From January 2020 to the end of August 2020, COMAR received 24, 271 asylum requests primarily from Venezuela, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Cuba. The COMAR has four offices in Mexico in Tapachula, Tenosique, Acayucan, and Mexico City. The COMAR lacks adequate presence in the country, but recently, has inaugurated several installations in Monterrey, Tijuana, and Palenque, which is a positive step toward providing COMAR services throughout Mexico. However, there are several inconsistencies in COMAR policies and procedures that result in very serious barriers to protection.

Inadequate screenings:

In states where there is no local COMAR office, a COMAR official will conduct the asylum eligibility interview over the phone. Refugees International spoke with several organizations representing asylum seekers who stated that there are no official protocols for conducting phone interviews, so there are few controls or guidelines on where the asylum seeker can conduct the phone interview. Lawyers representing asylum seekers in Mexico told Refugees International that phone interviews were sometimes conducted in public spaces where the asylum seeker has no privacy. Such conditions can make it uncomfortable for the asylum seeker to recount painful or traumatizing events, which may have bearing on their case. Done properly, these interviews can take an hour or more to fully capture the details and reasons the person is seeking asylum. However, according to civil society organizations with which Refugees International spoke, some phone interviews often last less than 30 minutes and are not detailed enough to obtain all the information necessary to make an informed resolution.

Additionally, the COMAR gives little notice to asylum seekers regarding the date and time of their eligibility interview. Several organizations that provide legal representation to asylum seekers noted that often the notice is so short that the asylum seeker does not have time to arrange for their lawyer to attend the interview. This frustrates the asylum seekers right to due process, specifically Article 20 of the Refugee Law, which allows for a lawyer to accompany the asylum seeker throughout asylum proceedings. These issues are especially problematic because the eligibility interview is the most crucial stage in the asylum process.

Growing backlog of claims:

Due to a substantial increase in asylum applications, limited staff, and bureaucratic challenges, there is a growing backlog of unresolved asylum claims in Mexico. According to estimates, in January of this year, 63,860 people were waiting for an asylum decision in Mexico and more than 6,000 had been waiting for a decision for over a year. By June 2020, the backlog stood at 35,468 claims, which shows a reduction in the backlog and is good progress that Refugees International welcomes. Despite this progress, Refugees International spoke with lawyers who indicated they represented asylum seekers who had been waiting over two years for COMAR to resolve their claims. This backlog is particularly problematic given the barriers asylum seekers face in accessing work and government services during their waiting periods, such as lack of access to the humanitarian visa and having to remain in states with few work opportunities. Thousands of asylum seekers grow tired of waiting such extended periods and abandon their claims. According to Asylum Access, in 2019, 10,000 asylum seekers abandoned their claims after waiting an average of 164 days.

It is worth noting that for years, the COMAR has applied the Cartagena Declaration to Venezuelans. But it recently began applying these same standards for evaluation to Hondurans and Salvadorans, which is a positive and welcome development. The application of the Cartagena Declaration means that asylum claims from these countries can be evaluated in less time because the criteria for evaluation can be applied quickly and requires less information from the asylum seeker to make a determination.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the COMAR continues to receive asylum requests. Yet, for cases submitted after March 24, 2020, the agency temporarily suspended its 45-day timeline for processing until further notice, meaning there is no longer a time limit to process claims. The COMAR has also reduced its in-office staff capacity to process claims. In the COMAR office in Tijuana, for example, only two staff are currently working to process claims. The reduction in staff and the suspension of the 45-day limit adds to the backlog and the time it takes for cases to be resolved.

Remaining in the state of asylum application:

Under Mexican law, asylum seekers must remain in the state where they submitted their asylum request and are required weekly to sign a form in the state’s COMAR or INM office to prove their presence. This restriction places an undue burden on asylum seekers. Most asylum seekers in Mexico apply in southern or northern border states. Southern states like Chiapas (where 60 percent of asylum requests are submitted) have some of the highest poverty rates in the country, and there are fewer work opportunities in these states. Mexico’s northern states have high rates of violence and crime and a large cartel presence. Asylum seekers are forced to stay in areas where they may not be able to provide for their basic needs, or where they are at higher risk to their personal security.

Asylum seekers cannot apply for asylum in one state and transfer their request to another COMAR office unless they meet several strict requirements for transfer. The COMAR only allows a transfer for security reasons, and asylum seekers need to provide thorough documentation of a security-related incident, such as a police report. For many asylum seekers, making a police report in a foreign country is a daunting and difficult process, and they may be afraid of speaking with authorities.

30-day deadline to apply:

Under Mexican law, an asylum seeker must apply for asylum within 30 days of entering the country or provide justification for not doing so. The COMAR will review the case and determine whether the justification is adequate to allow for the asylum seeker to present their claim. If the COMAR determines there is good cause for missing the deadline, they will issue a waiver to the asylum seeker. Large discrepancies exist in the issuing of waivers: asylum seekers with lawyers are more likely to receive a waiver than those without. If the would-be asylum seeker does not apply within 30 days and does not receive a waiver, Mexico can deport or voluntarily return this individual, despite the individual having international protection concerns.

Lack of coordination in issuance of key documents.

Once an asylum claim has been submitted, the asylum seeker must be issued a Constancia, an official document that formally certifies the person is an asylum seeker and is following an asylum procedure before COMAR. The Constancia also protects the asylum seeker from deportation. Although it does not prove legal status, the INM requires a Constancia to issue the humanitarian visa that facilitates the asylum seeker’s access to work opportunities, health, and education services.

Despite the current long duration of asylum procedures, lawyers told Refugees International that COMAR is taking months for the issuance of the Constancia, leaving asylum seekers without protection against deportation, and hampering their access work, healthcare, and other services. According to some NGO’s, the delay in the issuance of the Constancia also depends on the capacity of COMAR local offices. In Tapachula, the Constancia is issued within 24 to 48 hours, but in other states the issuance takes much longer. This problem reflects a lack of coordination between COMAR and INM to jointly address the consequences for COMAR of the substantial increase of asylum claims since 2017, as well as the aggravated vulnerability of asylum seekers due to the pandemic.

Recommendations

To the Mexican Federal Government:

- Establish an external INM oversight committee. The INM requires meaningful external accountability and oversight mechanisms. An independent oversight committee established by the Mexican federal government could play such a role, with a particular focus on practices that run afoul of Mexican and international law on protection of asylum seekers. This independent committee would work in conjunction with civil society participation. This oversight should also include a focus on protection of the human rights of all migrants within Mexico.

To the INM:

- Place communication materials explaining the option to seek asylum in visible areas within migration stations. Posters, leaflets, and other communication materials are ways to transmit information to detained migrants about their rights to seek asylum. These materials should be translated into most common languages spoken by migrants—French, English, K’iche, and Mam.

- Ensure the humanitarian visa is provided to all asylum seekers and to migrants who meet the criteria to enter Mexico for humanitarian reasons—that is, asylum seekers, stateless people, or those who fled because of public-interest or majeure force reasons. By providing broader access to this document, more people will be able to obtain much-needed services and reduce their risk of vulnerability. The INM should also adapt the legal and practical requirements to enter Mexico for humanitarian reasons and ensure that those in need of international protection and humanitarian assistance have legal access to Mexican territory.

- Agree to allow a COMAR official at the migration station inside Mexican airports as recommended in the MIRPS National Plan. If a COMAR official is present in airport migration stations, individuals with the intention of applying for asylum in Mexico can begin asylum proceedings immediately without risk of being returned.

- Allow civil society organizations access into detention centers. Civil society actors should be allowed to visit migration stations to provide legal counsel for detained migrants. This access can help ensure that migrants are aware of their right to seek asylum if they wish, and also can provide greater transparency of INM detention procedures.

To the COMAR:

- Broaden the criteria for transfer of asylum requests to different states. The COMAR should permit asylum seekers pursuing livelihood opportunities in states outside the state of asylum application the ability to transfer requests to another state. This can be done by including economic motives as a permissible reason for transfer. The COMAR should also be more flexible in the evidence it accepts justifying a change for security reasons.

- Allow more flexibility in assessing the 30-day deadline to apply. For asylum seekers who do not meet the 30-day deadline, the COMAR should allow for more flexibility in its analysis to permit the asylum seeker to present an application

- Create a protocol for phone interviews with standards based on UNCHR’s pandemic criteria for asylum eligibility interviews. The COMAR should create an official protocol for phone interviews that is in accordance with the standards that UNCHR recommends for in-person asylum eligibility interviews. These criteria should include ensuring the asylum seeker has access to a private space for the interview and that sufficient time is spent to capture the necessary details for the asylum request.

- Provide sufficient notice before the eligibility interview. The COMAR must provide at least one week’s notice of the eligibility interview so that asylum seekers are able to inform their lawyers and gather the necessary materials they will need for the interview.

- Improve coordination between the COMAR and INM in issuing Constancias to ensure that the Constancia is issued in a timely manner. The COMAR should immediately notify the INM that the Constancia has been issued to facilitate the INM’s subsequent issuance of the humanitarian visa. The 45-day renewal should also be eliminated, given the length of time asylum requests take to resolve.

- Early screening for high risk cases. Asylum seekers from Honduras and El Salvador should receive immediate or early screening at border areas to identify cases where the Cartagena Declaration standards could be easily applied to the case. This would simplify the asylum process, as the eligibility interviews could be done faster, and the criteria more rapidly determined for faster processing in cases where the asylum seeker is high risk and likely to be granted their asylum request.

To the UNHCR:

- Incorporate the improvements recommended to the INM and the COMAR into the Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework (MIRPS) 2021 Annual Plan for Mexico. The MIRPS annual plan sets out the priorities, commitments, and actions for each country to improve their international protections systems. Through the MIRPS, the UNHCR can support the Mexican government in implementing the practical changes outlined in this report with the technical and financial support needed, along with monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, to ensure the action we recommend take place.

- Continue to work with civil society organizations to provide trainings to the INM. The UNHCR should also provide regular trainings to INM alongside other civil society organizations on proper procedures for accepting asylum requests in states with no COMAR office, on providing accurate information to detained migrants on applying for asylum, and other asylum-related procedural issues.

To the U.S. Government:

- Transform U.S. policies on protection and asylum at the U.S. southern border. As Refugees International has demonstrated in other reports, the U.S. government has sought to end asylum at its southern border as a meaningful option for those fleeing persecution. A transformation of U.S. policy toward respect for the human rights of asylum seekers would have a significant and substantial impact on Mexican domestic policy. While the issues of U.S. domestic policy on asylum are beyond the scope of this report, it is important to recognize their critical importance.

- Scale up funding to assist in the implementation of these procedural fixes. The United States can continue to bolster the Mexican immigration system and its support to the MIRPS by providing additional funding for Mexico’s asylum system. This funding should not be in lieu of repairing the United States’ own asylum system, but rather to complement the transformation of U.S. policies on protection and encourage the responsibility sharing goals of the MIRPS.

- Roll back pressure campaigns that force Mexico to double down on enforcement. The United States’ influence is unquestionable in Mexico’s increased willingness to detain and deport migrants before they have a chance to seek asylum. The United States should work with Mexico as a partner in regional migration management rather than shifting responsibility and blame onto Mexico.

Conclusion

The international protection system in Mexico has the potential to be generous and fair but is impeded by a range of factors that prevent people with international protection concerns from accessing their rights and benefits. Although funding, political will, the COVID-19 pandemic, and U.S. pressure are considerable challenges to overcome in providing for a fair system, there are several practical changes that the Mexican government can undertake. If the INM and the COMAR undertake these changes, the impact will be extraordinary for the lives of the thousands of people who seek international protection in Mexico.

Refugees International would like to thank Daniela Gutiérrez Escobedo for her research and writing contributions to this report.

Cover Photo: Dozens of Central American migrants stranded at the Ceibo border crossing between Mexico and Guatemala were taken by the Mexican authorities to detention centers for migrants in Mexico. Photo by Jair Cabrera Torres/Picture alliance via Getty Images.