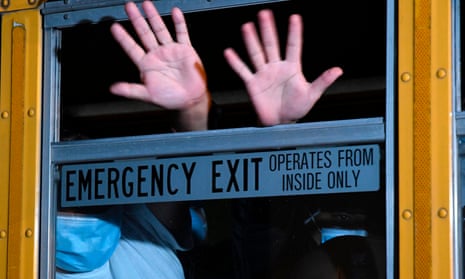

US authorities have radically accelerated the expulsion of unaccompanied children to Guatemala, but advocates accuse the Trump administration of using the Covid-19 pandemic as a pretext to rob vulnerable youngsters of asylum protections enshrined in US and international law.

Since tighter migration controls were announced in March, the US has deported more than 1,400 unaccompanied minors to Guatemala, according to data from the Guatemalan Migration Institute. A total of 407 children were expelled in October alone.

In comparison, in the whole of 2019, the US deported 385 unaccompanied minors to Guatemala.

US officials cited the threat of coronavirus when they invoked Title 42, a previously obscure clause of the 1944 Public Health Services Law, to justify the crackdown.

The law, which gives the government the power to take emergency action to prevent “introduction of communicable diseases”, orders the immediate expulsion of migrants detained between ports of entry. It also denies nearly everyone who arrives at the border the ability to apply for asylum.

Migration legal advocates argue the measure violates migrants’ rights to access the asylum process.

“Without a court order currently blocking the Trump administration from subjecting unaccompanied children to these rapid expulsions, children continue to be denied their right to seek protection in the United States,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a lawyer and policy counsel with the American Immigration Council.

“Under the Title 42 expulsion process the government has argued that public health laws override all normal immigration laws, and allows them to deport children without ever giving them their right to seek protection,” he said. “The Trump administration has taken what are generalized quarantine powers and interpreted into the powers the authority to expel people and override normal immigration law, which is why we say this is an unlawful policy.”

The surge in the repatriation of unaccompanied minors comes at the same time as the a sharp rise in the deportations of Cameroonian and other African asylum seekers, many of whom are alleged to have forced to sign or fingerprint their deportation orders.

According to Witness at the Border, an immigrant rights advocacy group, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (Ice) carried out 129 flights believed to be deportations, more than any other in 2020, including months before the start of the pandemic.

In July, the Associated Press revealed that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) was housing unaccompanied minors in hotels before expulsion. That policy was halted by a federal judge in September, but rapid expulsions of minors have continued.

On arrival in Guatemala, child migrants are taken into the care of the presidency’s social wellbeing secretariat and lodged in a shelter in Guatemala City before being reunited with their families.

Organizations from civil society like the Pop No’j Association, which works within indigenous communities across Guatemala, often help migrants return to their homes. The organization also assists with psychological attention for minors who have suffered the trauma caused by the deportation and expulsion.

Many of the children’s families lack the money to pay for their return to their communities.

“The majority of families do not have the economic resources to travel to Guatemala City,” Silvia Raquec, the coordinator of immigration issues for Pop No’j, told the Guardian.

The pandemic initially caused a freeze in migration through Central America, as countries closed their borders and imposed lockdowns.

But since then, the flow of migrants from Guatemala has steadily increased – not least because of the devastating economic impact of lockdown measures, according to Raquec and to apprehension data from US Customs and Border Protection.

“The conditions in countries of origin continue to worsen,” Raquec said. “The people continue to migrate, and people continue to have the idea that it is easier to pass with children, which isn’t true.”

According to Raquec, a large number of younger minors migrate with family members or acquaintances, but are separated upon apprehension by the CPB agents.

“The reality is that they are not going alone, they are going with a family member or a neighbor,” she said. “You are not going to find a child who goes to the US alone, there is normally an adult accompanying them. They are converted into unaccompanied minors at the moment of detention.”