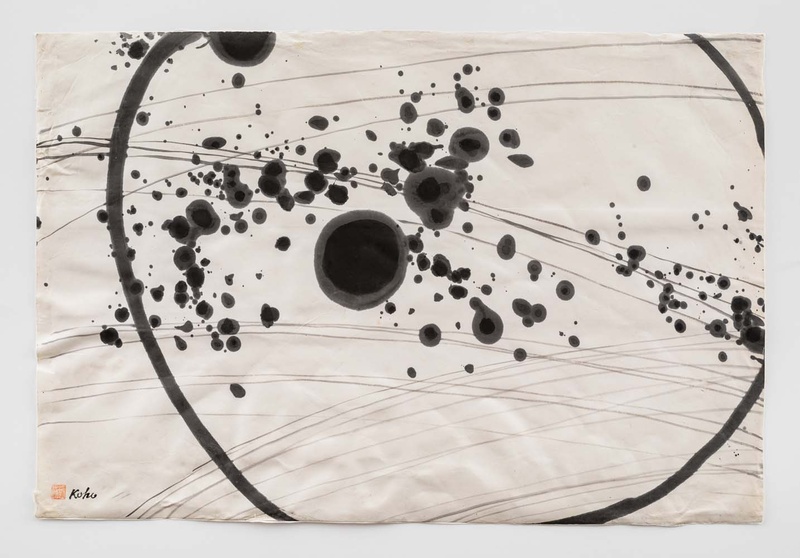

Was I looking at a pile of charred kindling, a set of raven’s wings or feathers?

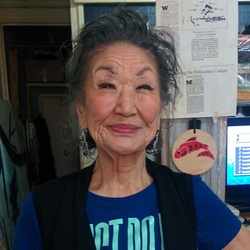

“I’m interviewing this 99-year old Kibei Nisei artist, Koho Yamamoto,” I wrote on my social media page, with a link to her 2021 exhibit. “Anyone heard of her?” I’d been sent a press kit to Yamamoto’s show, Under A Dark Moon at New York City’s Noguchi Museum, and was immediately struck by her powerfully evocative sumi-e paintings. Her life story and artistic path reminded me of Kibei Nisei Tacoma artist Fumiko Kimura, who I wrote about last year for Discover Nikkei.

Based in Seattle, Mayumi Tsutakawa was one of the first to respond. Mayumi is a Japanese American freelance arts writer focused on communities of color.“The fact that we do not know about her,” she wrote, “underscores the distance between [East] Coast and [West] Coast JAs, due to immigration patterns, escape from the Camps, and lack of API art writing.” She is working on a project focused on Kibei Nisei artists.

And indeed, this omission based on distance seems to be relevant for Koho Yamamoto, or “Koho Sensei” as she’s more commonly known. Yamamoto has exhibited in galleries in New York City. For decades she taught sumi-e painting at her art school between Soho and Greenwich, which she opened in 1973 and only just closed it in 2010, though she continues to teach at her small New York apartment. “I come from a family of teachers,” she says over an April 2021 Zoom interview, “and well, it’s a good way to make a living.” When her school closed, it was covered in the New York Times. At 96 she modeled for the designer clothing line Frank DeBourge.

Many of Yamamoto’s students and fans asked for a show of her own work, which is now showing as an exhibit at the Noguchi Museum until May 23, 2021. The 10 paintings, all untitled, are from the artist’s collection. Dakin Hart, Senior Curator for the Noguchi Museum, writes that Yamamoto’s work “combines a mastery of the techniques and traditions of Sumi-e with an atomic era sensibility, the brash bravura of postwar abstraction, and a disdain for the conventions of restraint her own teaching represents.”

But Yamamoto has roots which extend to the West Coast and Japan as well. Born in Alviso California, the daughter of a teacher and a calligrapher, she spent her early childhood years (from ages four to nine) at a temple in Japan. They lived with an aunt whose husband was priest at the temple. When she was four years old her mother passed away. “She was a graduate of a teachers college,” Yamamoto says proudly. Her father, a poet and calligrapher, encouraged her to pursue art. But her interests in art really came alive in camp.

“We had a lot of time,” she says now.

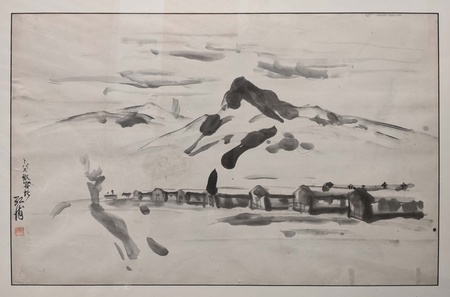

At the Tanforan Art School near San Francisco California, she studied oil painting with artist George Hibi and Sumi-e painting with renowned artist and professor Chiura Obata. The classes were small, she remembers, about 6 or 7 students. At first they painted on old newspapers, and then later on rice paper with supplies obtained or donated from outside. She remembers Hibi as “very nice,” and Obata as “full of life.”

Yamamoto quickly became a special student of Obata’s, becoming one of several to receive a special artist name from him, “Koho.” In the tradition of Sumi-e masters, Obata bestowed a version of his name on two or three of his most proficient students. Obata’s name means “thousand harbors,” and “Koho” means “red harbor.” “It was an honor,” says Yamamoto. At the Topaz concentration camp she continued to study with him until her family was transferred to Tule Lake in 1943.

After Yamamoto and her family were released from Tule Lake, Yamamoto moved to New York City. She was active in the Art Students League where she followed the rise of in Abstract Expressionism. She reached out to Isamu Noguchi, who called her paintings “exceptionally beautiful.” She married, divorced, and continued to paint, exhibiting in solo shows and group shows.

As a teacher, Yamamoto is well-known and beloved. She encourages students to empty their minds when painting, to “become nothingness.” How do we accomplish this? “You don’t think of anything. Just calm your mind and become nothingness and...it takes a little training,” she chuckles.

“With sumi-e, I love the fact that painting can be potentially made up of one perfect brush-stroke,” writes Jaya Duvvuri, a student of Yamamoto’s since 2008. “I have seen this happen with Sensei over the course of the years she taught and demonstrated to her students. I am also drawn to the meditative quality of it in trying to become the object that you paint, making a brush-stroke and not going over it again - the way sensei taught us. Sensei likes to say, 'when painting bamboo, be the bamboo'.

“Sensei is a wonderful teacher, very attentive, and encouraging,” Duvvuri continues. “She is known for her abstract style, but she has done outstanding representational artwork as well. Sensei teaches in the traditional way, first bamboo, then pine, plum, chrysanthemum, and orchid as these make up the keystrokes of sumi-e style of painting. Her critique is always impeccable, and she is very generous with sharing her wealth of knowledge in the medium. Sensei is also a wonderful company - she serves green tea and cookies during her classes with traditional Japanese music playing in the background, and she regales us with stories about her camp life and numerous anecdotes from her long eventful life. Her story is an inspiration - that someone can come out of the mud blooming like a lotus.”

It’s understandably difficult for Yamamoto to recall her early childhood years, but Yamamoto’s eyes light up when asked about teaching her students.

“Just become one with your painting and don’t think about other things,” she advises. “Just become what you are painting. Just dive into it. Don’t think about it too much. And be bold. You can’t be scared. You have to make mistakes.”

© 2021 Tamiko Nimura