The last few years have been marked by Big Food corporations exploiting and endangering workers, ripping off farmers, and jacking up grocery prices to pad their profits, but 2023 is a chance to turn the page. Congress is gearing up to write a piece of legislation it calls a “farm bill,” and even though you’re probably not a farmer (fewer than 2 percent of people in the United States are), I’m here to tell you why this should matter to you. Here are six reasons.

1. Because you like to eat

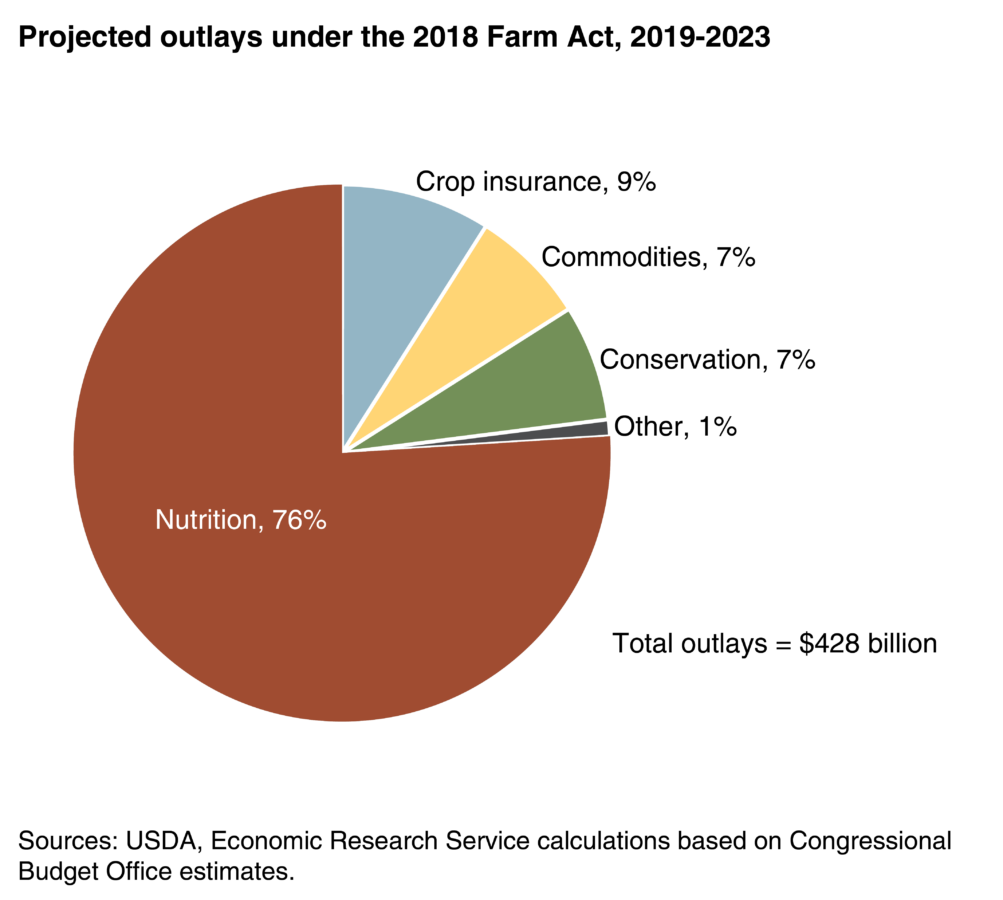

The first thing to know about the farm bill is that its name is misleading—measured in dollars, today’s farm bill is far more about food: more than three-quarters of the $867.2 billion in federal spending authorized by the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 goes to nutrition programs operated by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which help low-income households put food on the table.

More about that in a minute. Because even apart from the hundreds of billions of dollars invested in food aid and poverty reduction, the so-called farm bill shapes the US food supply in a variety of ways. It governs, for example, the taxpayer-subsidized Federal Crop Insurance Program and its rules about which crops are insured against losses, and that has a huge impact on what farmers choose to grow—today, that’s mostly corn and soybeans eaten by livestock rather than people. On the other hand, the farm bill funds much smaller initiatives like the Farmers Market Promotion Program, which invests in building local and regional food systems so more people can have access to fresh, local fruits and vegetables.

Shifting what the next farm bill invests in can re-shape the future of our food supply. Better to call it the “Food and Farm Bill.”

2. Because too many of your neighbors are (still) hungry

As noted above, the vast majority of the Food and Farm Bill’s dollars are used to fund food aid programs, most notably the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, once known as food stamps. The nation’s most important anti-hunger program, SNAP helped an average of 41 million people in this country get enough to eat every month in 2021. In addition to helping put food on the table in millions of low-income households, SNAP acts as an effective economic development program in communities with high usage rates, because people tend to spend food assistance dollars near where they live—a former colleague wrote about that economic multiplier effect on this blog in 2018. The need for, and positive benefits from, SNAP were clear then (when Congress and the previous administration were trying every way they could think of to cut SNAP benefits), they were clear during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic (when usage rates spiked and a different Congress increased benefits), and they are clear today.

But this month, the USDA will end the pandemic SNAP expansion, which could push many households over a so-called hunger cliff, even as some in Congress are reviving old plans to slash SNAP’s budget. But it doesn’t have to be this way. A new Food and Farm Bill could ensure that every person in every community in this country has enough to eat.

3. Because you want urgent climate action (and clean water isn’t bad either)

Despite this winter’s frigid temperatures, the world is on fire. You know it, I know it, and even some of the last skeptical holdouts—farmers—know it. Climate change is an emergency for a million reasons, and the long-term viability of farming and our food supply is one of them. Last year was yet another year of devastating weather events linked to climate change, and many of them hit farmers and farmland hard. California’s drought alone cost agriculture $1.7 billion in 2022. And remember that federally subsidized crop insurance program I mentioned earlier? An analysis of the program’s data nationwide from 1995 to 2020 showed that payouts for losses due to drought rose four-fold, while payouts for excess rain and flooding rose three-fold. In all, nearly two-thirds of claims paid during that period were for those two climate change–driven weather events and, without action, we can expect the costs to keep rising.

How can a new Food and Farm Bill help? By dramatically increasing funding that will help farmers fight back, by adopting practices that build healthier, more sponge-like soils. A 2017 Union of Concerned Scientists report showed how diversifying croplands with deep-rooted perennial crops and off-season cover crops and improving livestock grazing systems would make farmland more resilient to the effects of climate change. We found that building healthier soils could reduce runoff in flood years by nearly one-fifth, cut flood frequency by the same amount, and make as much as 16 percent more water available for crops to use during dry periods. And the same practices can deliver other benefits: Bringing down fertilizer and pesticide use. Improving crop yields. Reducing runoff that pollutes rivers and lakes, drinking water, and coastal waters like the Gulf of Mexico. And increasing carbon storage in the soil, making farms part of the climate solution. When Congress invested $40 billion in these practices last summer in the Inflation Reduction Act, I wrote that it gave me renewed hope. Now I hope a new Food and Farm Bill will do even more to protect our soil and water and safeguard the future of farming and our food system.

4. Because you support science-based solutions

With all the challenges facing our food system, we need new research to answer important questions and point to new and better solutions. Investment in public agricultural R&D has been shown to generate average returns to the US economy of $20 for every dollar spent, yet, over the past two decades, federal funding for agriculture and food research has fallen by a third. And the USDA is still dealing with the anti-science damage done by the previous administration.

A new Food and Farm Bill should prioritize systems research that approaches farming, climate and the environment, and nutrition and health equity as interconnected issues and works across disciplines to identify common solutions. This intersection, known as sustainable nutrition science, could hold the key to solving some of our most pressing public health challenges—but, until recently, there has been little federal funding to support it: just $15.7 million each year, less than 25 cents out of every thousand dollars in federal research funding. We also need more funding for research to advance agroecological farming systems and practices that support long-term climate change mitigation and adaptation, including the accurate measurement and modeling of soil carbon sequestration. And Congress should prioritize funding for minority-serving institutions and those engaging in collaborative partnerships and community-based partnerships and participatory research; we recently sent the USDA some ideas about that.

5. Because you value fairness

Though inflation is slowing, we’ve all seen higher prices at the grocery store over the last two years. You know who isn’t seeing that money? The people that grow, harvest, and package our food. Corporate consolidation—in which a handful of giant companies control too much of our food system—has allowed those companies to rake in record profits at the expense of farmers, workers, and consumers. Essentially, big industrial agriculture corporations have hijacked our food system for their own benefit.

A 2021 White House report put the meat and poultry industry under the microscope and showed how “significant consolidation” in the beef, pork, and poultry industries had enabled big processors including Tyson Foods to gouge both farmers and consumers. In his State of the Union speech, President Biden called on Congress to take on corporate consolidation and its excesses across our economy, and his secretary of agriculture has called for farm policies that can help “the many” rather than the few.

At the same time, fairness also means stamping out discrimination and inequitable outcomes throughout our food system, including on farms. Agriculture and the family farm hold a special place in our collective memory, but for some families, the memories are tinged with grief and loss: the powerhouse US agriculture system was built on the labor of millions of enslaved Black men and women. In the years after emancipation, Black farmers struggled to succeed in a system of sharecropping. Still, in 1920, Black farmers accounted for 14 percent of all US farmers, collectively owning approximately 15 million acres of farmland. But institutional racism and antiquated property laws drove massive Black land loss and, by 1982, Black farmers represented less than 2 percent of the nation’s 2.2 million farmers. By 2017, that number was down to 1.6 percent. Consolidation of US farmland into ever-fewer hands has proven especially bad for Black farmers, and an entrenched culture of discrimination at the US Department of Agriculture has denied Black farmers loans and other assistance for decades.

Two bills in Congress—the Food and Agribusiness Merger Moratorium and Antitrust Review Act, introduced last year, and the Justice for Black Farmers Act, reintroduced last month—would take steps to make our food system more fair. The first bill would curb corporate excesses and promote competition in the food and agriculture sectors, while the second would enact policies and provide funding to end discrimination at the USDA, restore land lost due to past discrimination, and help a new generation of Black farmers get started. A new Food and Farm Bill should incorporate these fixes, reining in corporate power and remedying centuries of injustice.

6. Because better food = better jobs

My colleagues and I have documented the indignities and harm borne by many who work in our food system—particularly farmworkers and meatpacking workers—and almost exactly a year ago on this blog, we wondered whether 2022 could be “the year of the food worker.” It wasn’t. But 2023 could be the year that a farm bill finally addresses the needs of the people who actually make our food system run. The Protecting America’s Meatpacking Workers Act is a start, recognizing how meat and poultry workers have been treated as expendable—during the early days of the pandemic, when thousands were sickened and hundreds died, but even before then, when workers in the industry suffered injury rates among the nation’s highest. The bill would take much-needed steps to ensure that these workers have safe, healthy workplaces where they are treated with dignity and respect.

The new Food and Farm Bill should incorporate these efforts and do much more: invest in the people who plant, harvest, process, transport, sell, and serve our food and ensure safety and a living wage, along with access to health care, clean housing, and the right to organize and join a union. It should protect food and farm workers from pesticides, extreme heat, and exploitative labor practices, and strengthen the consequences for employers that endanger their workers. And it should support the aspirations of farmworkers who wish to become farmers, and access to citizenship for food workers.

A Food and Farm Bill for (and by) everyone!

You can see from the length and breadth of this post just how sweeping the Food and Farm Bill is. There are so many ways (not just six) that this legislation could make our food system stronger, more resilient, more just, and more sustainable. We are all stakeholders in the Food and Farm bill, and as the new Congress begins to write it, they need to hear from all of us about it. You can start TODAY by urging your members of Congress to cosponsor the Justice for Black Farmers Act and help build support for racial equity in the Food and Farm Bill. Click here.