There's a moment in the trailer for Netflix's docu-series Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes that will stay with me for a very long time: A woman says, “He was charming, good-looking, smart... Are you sure you have the right guy?”

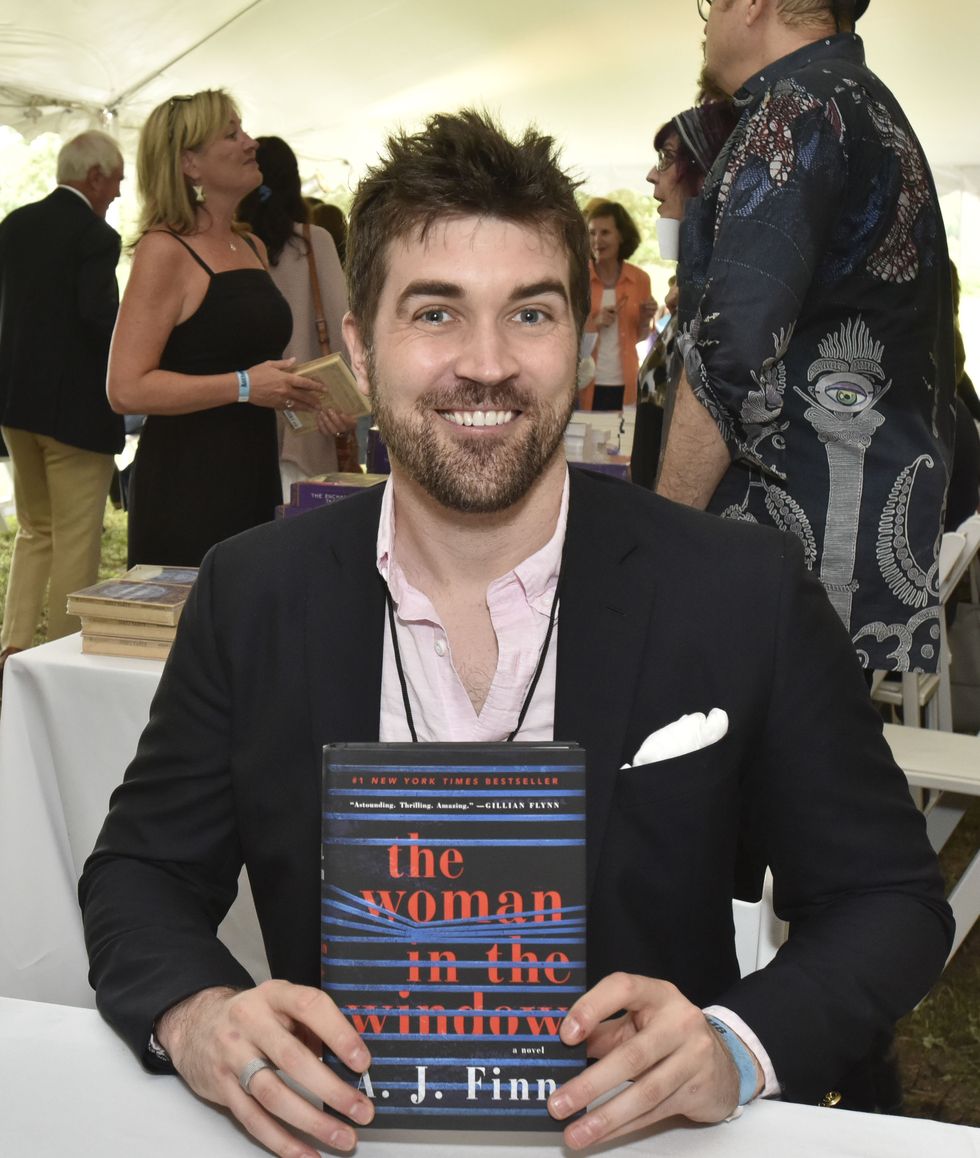

I have been devouring true crime stories for years, but this description of a sadistic murderer struck a chord because I’ve seen it applied in other situations. Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason’s Hulu documentary Fyre Fraud includes a director’s statement that describes Billy McFarland, creator of the disastrous Fyre Festival, had the “insidious charm of the fraudster.” Dan Mallory, whose bestselling novel The Woman in the Window was published under the pen name A.J. Finn—and who allegedly swindled gatekeepers of both publishing and academic institutions—was described in a recent New Yorker profile as a “charming young man” or “talented and charming.”

It might be presumptuous to compare McFarland and Mallory to Bundy—or even McFarland and Mallory to each other. And yet, these three men have deceived or upended the lives of unsuspecting people who crossed their paths, and their deceptions possess a common thread: their white maleness.

Thanks to the social constructs of racism and patriarchy, white men are inherently seen—in our popular culture and mainstream media—to be benevolent and socially apt. But these three examples are more cutting in their commonality. And somehow along the way, they have morphed the word “charming” from a compliment into a loaded, racialized term that’s primarily reserved for white men and the ways in which they can make anyone in their orbit look like fools. The charm offensive is a tactic that reinforces power, and many of us are taking the bait.

We live in the golden age of scamming. The most extravagant stories that we see placed in the biggest publications—or in mainstream films and television shows—are those about white people who almost got away with it. The language with which we used to describe these movers illustrates much about race and gender. Anna Delvey tricked New York City’s elite and is now getting a Netflix series in her honor. But Jessica Pressler, who broke the detailed story of her deceptions in New York magazine, put it bluntly when she asked: “Why this girl? She wasn’t superhot, they pointed out, or super-charming; she wasn’t even very nice. How did she manage to convince an enormous amount of cool, successful people that she was something she clearly was not?” Meanwhile, Caroline Calloway, the Instagram influencer who infamously fumbled a meet-and-greet and reneged on a major publishing deal, exhibits qualities of a cartoon princess—or, simply, “a self-obsessed mess.”

There is no emphasis on these women’s charms. That kind of praise is reserved for white men, because “charming” is not an acquired skill. It is no je ne sais quoi that someone is just divinely blessed with, and there’s no other logical explanation for it. The word “charming” in our current cultural moment is a portal to understanding power structures as we know it because of the scale of the crimes.

One of the biggest historical standpoints we have to charm and white malehood is none other than Prince Charming. In fairy tales, he is seen as the counterpart to a heroine, one who will his female victim, claim her as his own, and ride off into the sunset with his new prize. But deeper than that, the conception of a Prince Charming is illustrated almost exclusively through the white male body. This is what I ascertained when I thought of Ted Bundy’s most recent fans, those who have pined after a serial murderer because of his supposed good looks and his gift of gab. Their idealization of who they thought he could be was a curtain behind which his atrocities could be stowed away, whittled down to tertiary details of his life.

As for Billy McFarland, who had no experience in managing a music festival of that kind of grandeur, his passion for this project was enough to compensate for the areas that he lacked. Dan Mallory was able to lie for years about his expertise not just because he was charming, but because he reflected the other people in the room. (And he was able to gain sympathy for his flaws by overshadowing them with bigger, more sympathetic woes.) It’s easier to convince others of what you don’t possess when you do have the image they trust. Such compassion is not imparted to people of color, who often have to be twice as good to be acknowledged—and whose jobs and salaries may never reflect the depth of their expertise.

There’s no way that a man of color could have managed Dan Mallory’s fast-tracked career in publishing, from editorial assistant to editor and best-selling novelist. No man of color could command millions of dollars on a whim from top-level executives and for a music festival he had no experience in organizing without this indelible belief in his competency. And there’s no way a man of color could butcher and desecrate the bodies of young white women and still have female fans speaking of his allure in court—and, decades later, on social media. To accomplish any of these feats, there has to be something about these men’s presence that is unearned. But more than that, the way we assess these men reinforces that, unlike women like Anna Delvey and Caroline Callaway, their charm is indelibly rooted in their gender and race.

In order for one to deceive, there has to be a baseline trust. Who else in America is more trustworthy, more powerful, and more charming than a white man?