By Cathy Park Hong @cathyparkhong

Minor Feelings author Cathy Park Hong and Steven Yeun talk about the white gaze, Korean parents, and Minari’s subtle MAGA side-eye.

Steven Yeun logged onto Zoom from his car while he waited for his wife to return from a doctor’s appointment. I found this endearing, of course: a loyal husband!

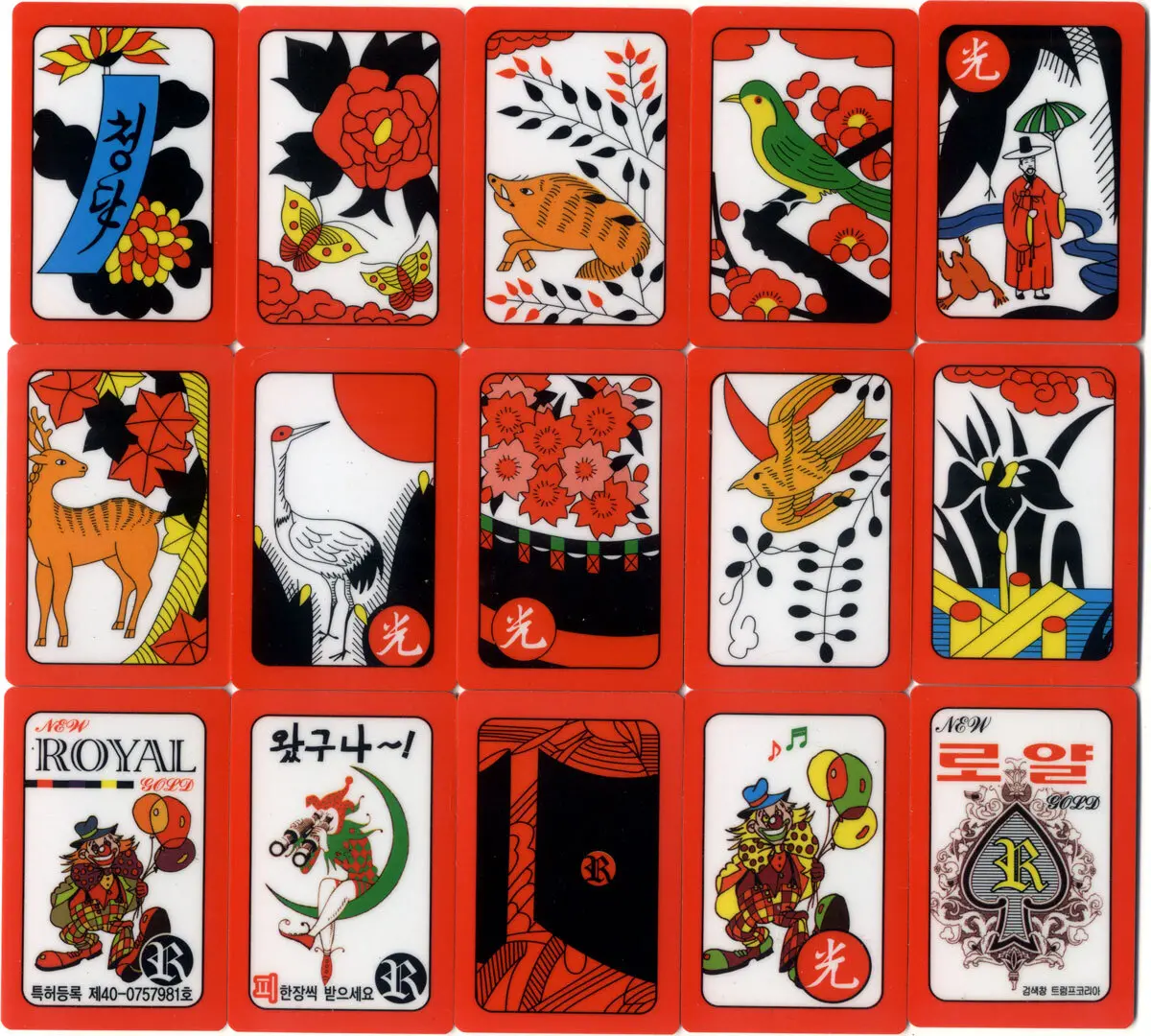

I’ve been a fan of Yeun since I saw him in Okja (2017) and then Burning (2018). Like great lead actors, he fills up the screen and holds your attention as his bright pretty face reveals a sly or sinister inner life in gestures as faceted as a gemstone. But because Hollywood shamelessly overlooks Asian-American actors and has belittled Asian masculinity for so long, the industry has underutilized Yeun’s incredible talents until, perhaps, now. In Lee Isaac Chung’s beautiful coming-of-age film Minari, Yeun stars in a lead role: a Korean immigrant father, Jacob, who moves his wife and two kids to a farm in Arkansas. Minari reminds me of Terrence Malick’s films, in the way it pays homage to the lush, sensory memories of director Lee Isaac Chung’s childhood. What makes this film distinctive is that the memories are so culturally specific to Korean immigrant life, such as the lingering shots of Hwatu cards or the pungent medicinal acupuncture brew that Jacob’s son David is forced to drink.

In person, or at least over Zoom, Yeun carries little of the darkness or eccentricities of his characters. He’s earnest and amiable. We talk about “immigrant brain,” how I’m surprised Yeun would ever read my book, and how he still feels like “a kid from the place in the middle.” He confesses being afraid he’ll get too comfortable in this interview, because I’m a fellow Korean. We joke about Yeun playing an ajeossi, a Korean stereotype of an avuncular middle-aged everyman, and then talk about how Jacob is actually not like an ajeossi at all. Jacob is younger, for one, and quietly intense and monomaniacal, placing his own need to succeed above his family’s well-being. Also, Yeun modeled Jacob after James Dean. When I expressed surprise at this, Yeun emphasized that Jacob is not a typical family man. He wants to escape the roles imposed upon him and be whoever he wants to be—which sounds a bit like Yeun himself, as he searches for roles where instead of being a proxy for a group, he can just be a proxy for himself.

Cathy Park Hong: I want to ask about Minari and the election. A record turnout of Asian and Latino people and immigrants helped turn some red states blue and helped others stay red. Georgia became blue, but Texas remained red. And this movie is about an immigrant family living in Arkansas. And when I think of Arkansas, I don't think Korean community. How do you want the film to be taken, in the wake of the Trump administration?

Steven Yeun: I want these characters to be seen in a truly human fashion. We tried not to put too much focus on their Asian identity for the sake of explanation. It was important to humanize our existence, and our parents’ existence. I see Jacob’s journey as representing a bigger understanding of some lessons, about how there are pillars upholding the family and societal structures, and it’s not just him. Every single person in his family—Monica, the kids, Grandma—is also doing the work.

But what resonates with me is how the movie recontextualizes the American dream, and how America can thrive. You look at this moment: We’re in a pandemic, and who are the people upholding society? It's the gap people, the people caught in between, immigrants, minorities, women. These are the people upholding society’s structures, and yet the conversation usually isn’t about them, which is bullshit. Immigrants and minorities have been living this life for a long time; this is nothing new. Last year was the first year that my parents have ever voted, because so far, in their minds, what's the point of them voting? They're invisible anyway, and society doesn't service them. They’ve been living this gap existence of being otherized, being a foreigner, and deciding to just take care of my area. When I think about that, I really understand how much they've internalized this separate place that they live in. I'm starting to ramble now—this is what I meant about being too comfortable.

Who are the people upholding society? It’s the gap people, the people caught in between, immigrants, minorities, women.

Hong: My mother also voted for the first time in the 40-something years that she's lived in the United States. Partly it’s because she lives in California, so feels it doesn't make a difference anyway. But even if she lived somewhere else she wouldn't think it mattered. I'm not going to speak for all Korean immigrants, but I think many don’t vote because they think politicians don't care.

Yeun: There’s a weird deference that comes from a place of thinking, They're allowing us to be here. Let them decide the president. My parents were 30-something when they came over, so for them, they just wanted to be able to make money, raise their kids, and be left alone. Minari was an exploration into seeing our parents in their fullness, and seeing how they also contribute to this place. Right now, people should be paying attention to how immigrants are, because we are all made immigrants by this situation. Not on a literal basis, but we're all thrown into exile and isolation, and sitting in between spaces.

Hong: Tell me about the red hat that Jacob wears. The red hat has become such a symbol of white power and a "get off my lawn," American way of thinking.

Yeun: So the one that fit my fat Korean head was this red one. I thought, Man, Trump really f—cked up red hats for everybody. Does it say something if I wear this? But it looked the best, so I didn't think much else about it, or make an active choice to make a statement. But while we were filming, I would talk to Isaac about the hat—should I wear my hat now or not? By the time we finished filming, I realized that Jacob wears the hat when he’s consumed by himself and a capitalistic sense of wanting glory. When he’s humbled by losing everything, he doesn’t wear the hat anymore. It was never a lesson for Trumpers; the hat is more like a pair of sunglasses. It's there to shroud the deep fear and pain that pervades the soul of this man. Jacob is never completely healed, and will never be completely good to his family all the time. But once he’s broken out of his pain, there is something about being humbled, about submitting to family, about understanding the interconnectivity between all of us. He learns he’s not the sole proprietor of the success and survival of his family.

Hong: While playing Jacob, were you thinking of your own father?

Yeun: Yes, but the battle in my mind was between thinking of my own father, literally, and the larger idea of all of our Korean fathers. Jacob is an immigrant of an immigrant. He comes to America to find prosperity, but he then leaves California to go deeper into the heartland to find his own land. What type of person is that, who leaves a safe space to search for who he is as an individual? Especially if you juxtapose that against Korean society and how I was raised, which is that you are who you are based on how other people say you are.

Jacob is trying to find himself outside of the system that indoctrinated him, and I saw that in my dad. He did well for himself in Korea. He was an architect at a pretty big firm, and bought a house in Seoul. He helped fund his younger brother's schooling. He always tried to find validation for himself, and when he took a business trip to Minnesota in the late 1970s, and he saw all this expansive land in Minnesota, he wanted that. He dreamed of going to America his whole adult life. But when he finally came here, to Michigan, it was so scary. My family quickly fell into the patterns that a lot of Korean-American families fall into, which is: find your community, find your safe space, find the places that you can occupy. But I didn’t want Jacob to be a basic ajeossi. My model for him was James Dean, someone who can see it all for what it is, because he lives at a different frequency.

Hong: A friend once said something to me about how Korean mothers and fathers will say they sacrificed everything for us so their children could have a better education. And she was like, "That's not true. You wanted to just escape your toxic parents," or "You wanted to get rich." There are these motivations, and these are probably the Koreans who were drawn to that more American ethos of individualism.

Yeun: Yes. Jacob wants to be more than a shill company man, or a cog in the wheel.

Hong: But I do think what made the movie feel true to me was how it gives you both cultures—like with the herbal medicine and the cards—and how it’s bilingual. The family switches between Korean and English, which is how I grew up. I've often been frustrated with Asian-American representation because it’s often in English, and not even an authentic Asian English accent.

There’s this white gaze, this cinematic language. We’re so deeply entrenched in it that we don’t even know where it ends and begins.

Yeun: The bilingualism comes from wanting to remove this family from the American gaze, or the white gaze. We even wanted to remove them from the second generation gaze. The language was scary. Not the Korean part, but the broken-English part. I've spent most of my career rejecting it, refusing to work on it because I said I wouldn’t do that shit. The shame of it really messed me up. There’s this white gaze, this cinematic language, which you write about in your book. We’re so deeply entrenched in it that we don't even know where it ends and begins. The people who are typically in power are learning to get a little bit out of the way, but there’s still a bubble that Asian or immigrant actors get caught in, of servicing the gaze even though filmmakers try to not put the gaze directly onto you. Perhaps a producer who's not of a certain culture is being told, "Hey, in order for this to sell, you got to explain it." The phrase “specificity is universality” gets used a lot, but I’ll be honest… f—ck that. Whiteness is still considered the neutral, and the majority. We’re being told, "You be more specific, so that I can access it."

Hong: In a lot of work you’ve done so far, I've never thought, Oh, he's representing this kind of person. But maybe you are in Minari, because there is a lot of symbolism attached to the American dream.

Yeun: We’re still on this journey. Isaac wrote a voiceover for the movie: "Minari grows, comes in the pockets of immigrants, dies in the first year, thrives in the second, purifies the water and the soil around it." It was a love letter to our parents’ generation, thanking them for their sacrifice and suffering. But then Isaac cut it. It was the coolest decision, because it retains our parents' humanity. It retained the fullness of them. They don't need to be juxtaposed against some sense of suffering in order to exist. And now Jacob and Monica and the grandmother can just be shown as who they are, flaws and all.