If anything has a knack of making presidents in otherwise commanding positions into one-term presidents, it is recessions of the U.S. economy.

Just ask Herbert Hoover, who lost in a landslide in 1932 during the Great Depression as unemployment reached 25 percent. That had been preceded by outright deflation, wherein inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931 and -10.3 percent in 1932.

Or Gerald Ford in 1976, who was president during the recession of 1973 to 1975, that saw inflation peak at 12.2 percent in Nov. 1974 and unemployment peak at 9 percent in May 1975.

Or Jimmy Carter in 1980 as inflation peaked at 14.5 percent in April 1980 and unemployment topped off at 7.8 percent in July 1980.

Or George H.W. Bush in 1992 as inflation peaked at 6.4 percent in 1990 and unemployment reached 7.8 percent in June 1992.

Or Donald Trump in 2020 during the Covid lockdowns and production halts as unemployment briefly skyrocketed to 14.7 percent in April 2020 as more than 25 million jobs were lost as the American people were paid to stay home.

Like clockwork, when bad things happen on the incumbent president’s watch, voters often end up saying it’s time for a change. One exception appears to be Ronald Reagan, who had a crushing recession in 1982, wherein inflation peaked at 10.9 percent in Sept. 1981 followed by peak unemployment reached 10.8 percent by Dec. 1982.

Given enough time between a recession and the reelection bid—Reagan had two full years of falling unemployment and inflation headed into Nov. 1984—it is possible for a president to right the ship of state. But that’s the exception. Usually, recessions are fatal. The reasons surrounding them often do not matter.

And, surely President Joe Biden is now facing a similar risk, where although unemployment is near record lows at 3.6 percent presently, numerous signals of an imminent recession are already out there: the 10-year, 2-year treasuries spread has been inverted for almost a year now, inflation peaked at 9.1 percent in June 2022 and now the Federal Reserve is projecting 4.6 percent unemployment in 2024 as inflation is dipping to 6 percent.

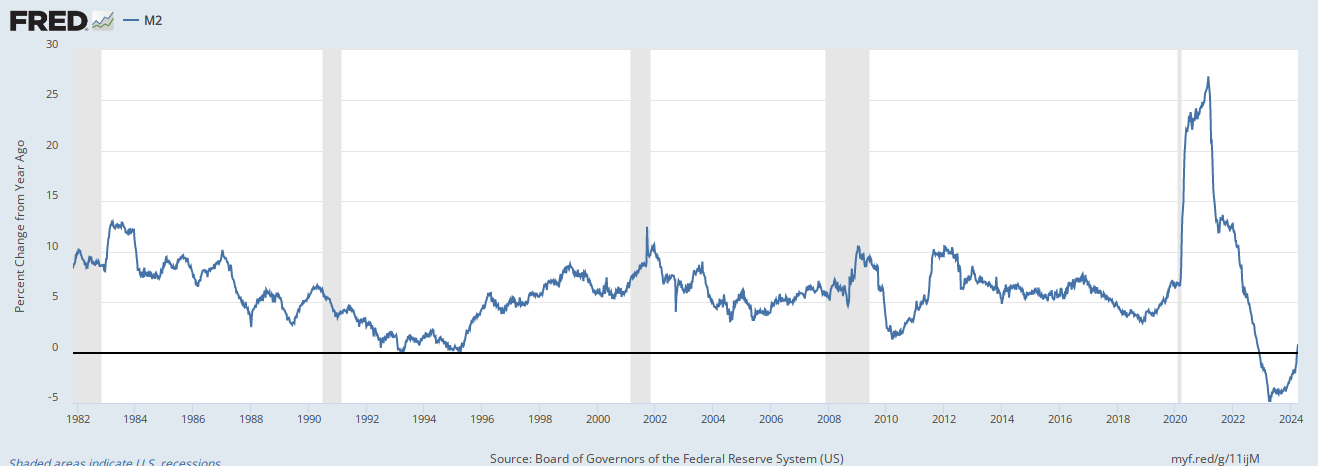

Ominously, the M2 money supply, which peaked at $22 trillion after it increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, after more than $6 trillion was printed, borrowed and spent into existence for Covid, has now decreased a bit to $21.1 trillion, and is down 1.9 percent over the past 12 months. One has to go back to the Great Depression and the banking crises of the late 1800s the last time that happened.

TERRIFYING – M2 money supply – this graph has only done this 3 times . pic.twitter.com/EiPnfYv5a3

— Grant Cardone (@GrantCardone) March 14, 2023

And now there is a string of bank failures to contend with. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank have been placed into receivership, and now the lack of confidence contagion is spreading to Europe as Credit Suisse is being rescued by the Swiss National Bank.

So, a recession is almost certainly already baked into the cake, no matter what policies Biden, the Fed and U.S. Treasury decide to pursue, with or without Congress.

Which brings us to the $31.4 trillion national debt ceiling. Prior to these bank runs, the Biden administration had been hoping to engage in a game of chicken with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), who has signaled he would like to freeze spending at 2022 levels of $6.27 trillion and simply ignore Biden’s massive new $6.37 trillion proposed budget.

The difference is a measly $100 billion, most of it, about $70 billion, on the discretionary side of the equation. But given the spending, borrowing and printing binge that Congress and the Fed have been on since Covid, a spending freeze is likely a very good idea, further helping to tame inflation, thus bringing down interest rates so that when we come out of the recession it’s not off to the races again as happened in the 1970s.

Biden on the other hand wants to keep spending more and more, and then when unemployment does go up, spending even more on top of that even though unemployment benefits and thus federal spending will automatically rise during the recession without Congress taking any action. He also thinks raving about Social Security and Medicare spending, or wagging his finger about a national default will get him what he wants.

But here, the President is wrong. No matter what happens to the U.S. economy on its current trend, Biden will get blame, likely making 2024 a tossup. If Biden wants to throw a national default on top of it because he could not do an easy to reach compromise on discretionary spending—again the difference between the two sides’ stated positions is just $70 billion of discretionary spending—that’s obviously on Biden, who appears willing to steer the ship of state into the abyss rather than cut a single penny from the budget.

“No compromise” and “$6.37 trillion or bust” as unemployment is skyrocketing and the global financial system is melting—which might very well happen regardless—are not exactly the catchiest reelection campaign slogans. But it’s his administration. When the economy goes down, usually so does the president.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.