LOS ANGELES — Sharon Yukiye Wu, 71, was born a decade after thousands of Japanese Americans were ordered to be imprisoned during World War II. But she’s heard stories about her great-grandparents, who lost their farms, their restaurant and their home when they were sent to the Poston incarceration camp in Arizona.

They both died before the U.S. government granted reparations to survivors. At the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles on Wednesday morning, Wu had the opportunity to consecrate their story.

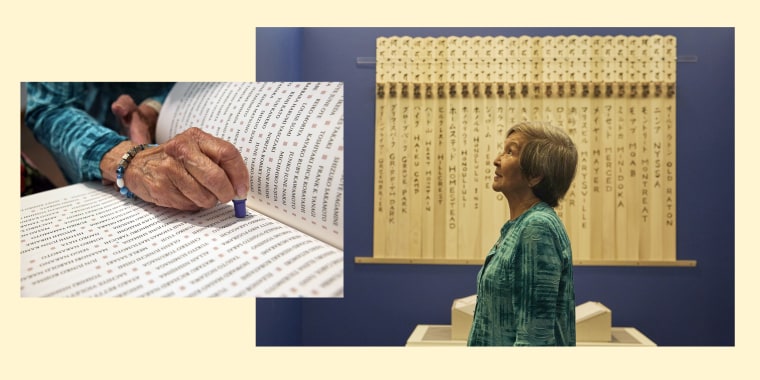

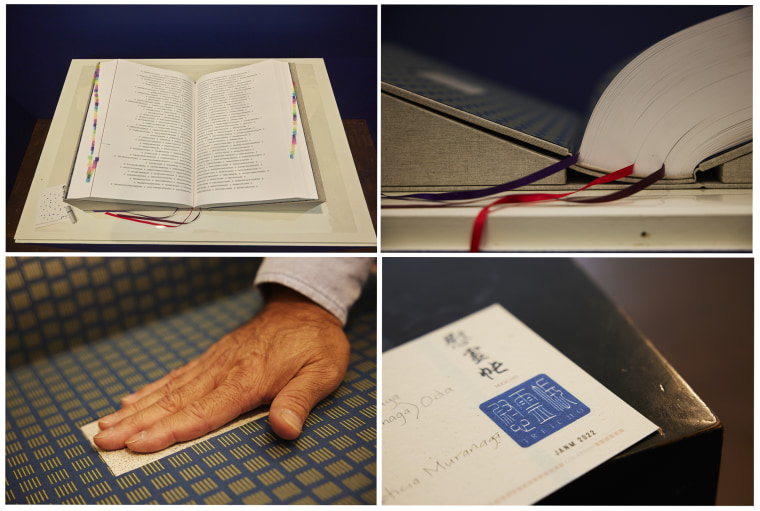

A first-floor exhibit includes a newly crafted 25-pound tome comprising the 125,284 names of the individuals of Japanese descent that were incarcerated — names that had never been collected in one place before. The walls surrounding the book are decorated with 75 wooden grave markers, or sotoba, each bearing the name of an incarceration camp and a glass vial containing soil from the site.

Wu found the names of her great-grandparents, Kanekichi and Yoneko Watanabe, and stamped a blue seal next to each. Marking the book, she said, was a form of redress that preserved their legacy.

“I wanted to make sure I honored their memory because they suffered and lost so much,” Wu said.

The book, called the Ireichō, will be on display at the museum for a year, during which survivors and their descendants can pay tribute to their loved ones. Because of the sacred nature of the book, each survivor is limited to two stampings. Starting next fall, the Ireichō will be shown across the country during an annual pilgrimage with events at former incarceration sites.

“There’s such enormous power in names,” said Ann Burroughs, the museum’s president and chief executive. “Having people be able to come and identify the names of their family members is a way of making this monument of the past be so present and so alive. It’s a way to heal and repair trauma.”

Burroughs also noted the historical significance of the museum itself, which sits on a plaza where, 80 years ago, hundreds of Japanese American families lined up and boarded buses to incarceration camps.

“I consider it to be one of those ground zero points in the civil rights history of this country,” she said.

The Ireichō is one phase of the Irei Monument Project, an interactive, multifaceted memorial founded by Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams, the director of the USC Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. Funded by a $3 million grant from the Mellon Foundation, the project includes a website that allows people to search the names of survivors and a number of light sculptures that will be installed at various former incarceration camps starting in 2024.

Clement Hanami, the museum’s art director and vice president of exhibitions, said Williams has compiled the most accurate and extensive record to date of Japanese American incarceration. In addition to the thousands of people imprisoned at the 10 major incarceration camps, like Manzanar, Heart Mountain and Tule Lake, Hanami said, Williams also accounted for those sent to smaller sites run by the Department of Justice and makeshift camps called “assembly centers.”

And since the book was unveiled to the public on Sept. 25, Hanami said, the list has grown. “People have come to us and said their family members aren’t in the book,” he said. “Then we’ll do research and potentially include them. It epitomizes the idea of repair.”

The Ireicho itself, Hanami continued, references the kakochō, a death register that’s placed in Japanese Buddhist temples and brought out during memorials so people can chant the names of the deceased.

“It’s a very Japanese and Japanese American way of respecting the ancestors and their histories,” Hanami said.

Nan Okada, 85, was 4 years old when she was sent to Camp Amache in Colorado with her parents and younger sister. When the exhibit opened in September, she stamped blue circles next to the names of her parents, Mikio and Dorothy Fujimoto.

Okada’s own name, meanwhile, was marked by her daughter, Jill. For both, the stamping was a cathartic experience.

“For us, this book represents a picture of closure,” Okada said. “You just see one name there, but that name represents a whole life, a whole family — generations. This book represents a picture of closure.”