A new initiative is aimed at raising awareness about a dark and often forgotten chapter of U.S. history: the secret bombing of Laos during the Vietnam War.

Nearly half a century later, most Americans — and even many young Laotian Americans — know little about the clandestine, nine-year, CIA-led military campaign informally called the “secret war.”

Unlike the Vietnam War, the secret war is seldom taught in U.S. schools. For Laotian elders, most of whom came to the U.S. as refugees during and after the war, the memories can be too traumatic to revisit. Some take them to the grave.

The mission of the Legacies Library, a project of the Washington, D.C.-based group Legacies of War, is to keep the secret war from being lost to time.

A small team of volunteers has begun compiling educational materials about the war, including documentaries, scholarly research and government documents, and uploading free digital versions online.

They’re just getting started, said Sera Koulabdara, executive director of Legacies of War.

“We’re trying to preserve this history so we can protect the future,” said Koulabdara, who was born in Laos but largely grew up in Ohio. “We wanted to encourage more people to write about it and take interest in their history, including the American public.”

It wasn’t called the secret war for nothing.

The Johnson and Nixon administrations each oversaw U.S. military operations in Laos — technically a neutral country — without informing Congress of the full scale of the American involvement.

U.S. bombers were pummeling communist supply lines on both sides of the Vietnam-Laos border, often with little regard for civilian casualties.

They dropped an estimated 2 million tons of ordnance during the conflict, making Laos, on a per-person basis, the most bombed nation in history.

Congressional hearings in 1971 made the campaign known to the public. But by 1975, the U.S. had withdrawn from Vietnam and a weary nation was ready to move on.

In Laos, the communist Lao People’s Revolutionary Party took power, which it has held ever since.

The impact of the secret war continues to be felt today, including the danger of unexploded ordnance.

About a third of the American bombs failed to explode on impact. Leftover explosives still saturate the Lao countryside, posing a threat to farmers and children. Some 50,000 people have been killed or injured by unexploded ordnance since 1964, according to AUSLAO-UXO, a company with Lao and Australian owners that provides clearance services.

As the war wound down, thousands of refugees left Laos, with a large share settling in the U.S.

According to U.S. government data, there are about 200,000 Laotian Americans, nearly all of whom trace their heritage to this time, while the Hmong American community, which also includes many refugees from Laos, numbers around 300,000. The Hmong are a separate ethnic group — with a language and cultural traditions distinct from Lao — who have over the last two centuries migrated from China into parts of Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asian immigrants from this era often bury war memories in a “culture of silence,” mental health advocates say.

Some research suggests this trauma can be passed down through generations, manifesting in a sense of rootlessness or a lack of Lao identity among descendants.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Legacies of War, formed in 2004, spent years pushing Congress to increase funding for bomb clearance in Laos. Its efforts paid off in 2016, when then-President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the country. He doubled annual support for ordnance clearance efforts to $30 million.

That started to address one legacy of the secret war, but another one loomed: Americans’ continuing lack of awareness about it.

The idea for the Legacies Library came in 2020, after Koulabdara found herself sharing memories with Jessica Pearce Rotondi, a journalist and author in New York she met through social media.

Both had spent years rifling through musty boxes, trying to make sense of the family histories their loved ones could never tell.

After her father died in 2017, Koulabdara found photos from his childhood, old journals and notes from his career as a surgeon in Laos.

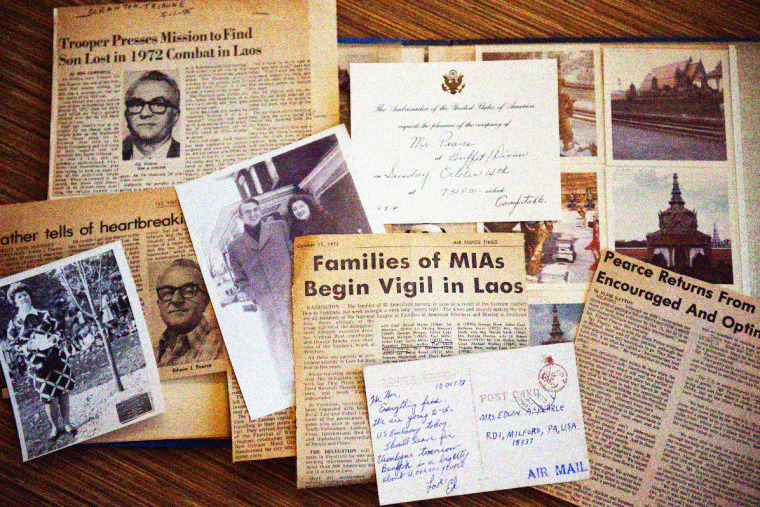

Rotondi had been researching her memoir “What We Inherit,” about her family’s search for answers about her uncle, an American pilot during the Vietnam War who never came home.

Searching her childhood home, she found boxes of heavily redacted, declassified CIA documents concerning his service, as well as stacks of letters that chronicled the family’s quest to find him.

Their exchanges convinced them of the need for more transparency about the bombing campaign in Laos.

“Those bars separated families and continue to keep Americans from knowing their history,” Rotondi said in an email, referring to the blacked-out portions of the documents. “Our goal with Legacies Library is to stop the silence around the Secret War.”

Two years later, the Legacies Library is taking shape.

Fact sheets and congressional testimonies offer a crash course on the continuing problem of unexploded ordnance in Laos. There are also links to books and documentaries selected by a Legacies of War review committee.

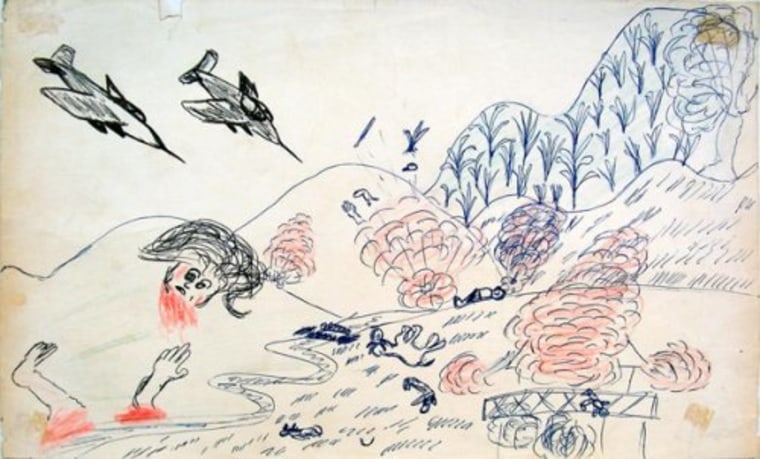

One of the library’s crown jewels is a group of 32 drawings by Lao villagers.

Collected by an American volunteer, Fred Branfman, in the 1970s, they depict what the U.S. air war looked like from below. They represent one of the only forms of direct testimony about the war by the Lao people.

Down the road, organizers hope to find funding for the library — it’s now run by volunteers — and add new, unique holdings.

One area where the library is lacking, Rotondi said, is its resources about the Hmong people, many of whom were key U.S. partners during the war. A museum in Minnesota, a state that nearly a third of Hmong Americans call home, commemorates that part of the story.

As for government materials, Sens. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I.,are supporting efforts to declassify more CIA documents.

Another prospect is to add oral histories. As they become grandparents, some immigrants from Laos have started to open up about their war experiences.

It’s the curiosity of younger generations, though, that may make a fuller reconciliation possible.

In February, Laotian Ambassador to the U.S. Khamphan Anlavan gave an award to siblings Hyleigh and Prinston Pan, high schoolers in California, for their work to commemorate the secret war.

Hyleigh Pan has gathered testimonials for Southeast Asia-related legislation and helped produce a documentary about unexploded ordnance in Laos. Prinston Pan has recorded more than a dozen oral histories and organized school fundraisers for bomb cleanup in the country.

He has also written a children’s book, “Kong’s Adventure,” based on the experience of his grandfather, who served as a police chief in Laos under the U.S.-backed government before fleeing the communist takeover with his family and starting a new life in Kansas.

All proceeds go to the Legacies Library.

In an interview, Prinston Pan said that talking to the ambassador felt familiar, like talking to his grandfather.

The award, he thinks, “comes from a mutual care for the Lao community in general.”

“Over time, someone has to take the step forward in healing those wounds from the past.”