From the outside looking in, it’s easy to speculate, in general terms, why professors seem to be fleeing higher education in increasing numbers. But it’s not every day one gets to hear from a scholar who spent years building specialized knowledge and expertise—landing tenure and a department chair—only to give it up and walk away.

Carrie-Ann Biondi, a philosophy PhD and Aristotle scholar, taught in universities for twenty-five years, becoming associate professor of philosophy at Marymount Manhattan College and chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies. But in mid-2020, she jumped ship. Here, she shares why.

Jon Hersey: Carrie-Ann, I feel lucky to count you as one of my friends, and when I went to visit you in January 2021, you shared some pretty upsetting news. After twenty-five years’ teaching philosophy, you’d decided to leave academia. I want to talk about the illiberal ideas on campus that drove your decision. But, first, I’d love to hear about the values that led you into a teaching career, specifically philosophy in higher ed.

Carrie-Ann Biondi: I’ve wanted to be a teacher since I was five years old. When I first started kindergarten, I knew I wanted to be in school all my life because I was excited by the whole experience of learning, and I also loved sharing what I learned with other people. My brother is a year younger than me; I’d race home and tell him all the cool stuff I was doing, then watch him learn how to do it. I loved that!

I thought, How can I do this all my life? And, of course, the answer was: Be a teacher. I went to college thinking I would teach younger kids. But I loved the college learning experience so much—the higher-level demands it required—that I said, “No, no, I’m going to teach at the college level.” I was an American studies major as an undergraduate. I studied ideas at the intersection of literature, history, and political science. But when I went to graduate school, I realized that American studies there wasn’t what I had been studying as an undergrad. It was a mash-up of some of the worst of the day’s culture, and I quickly thought, What did I get myself into?

But based on questions I was asking in one of my courses, somebody suggested I take a philosophy course. So, I enrolled in an epistemology seminar. It was the most difficult thing I ever took—and I loved it. So, I switched to majoring in philosophy, and eventually I became a college philosophy professor.

The values that led me to that were just the excitement of understanding the world and how it works. I enjoyed the intellectual stimulation and puzzling through interesting questions. But I could also do things with that knowledge, and the world was easier to navigate the more I understood it. I was also fascinated about why people understand things differently, why they hold different views, and how people have debated these views throughout history.

I wasn’t just interested in comparing ideas but in understanding why an idea is true or false and whether it is good or bad for one to live by. So, I was really interested in issues of justification, intellectual independence, and figuring out what’s true.

Hersey: Where did these interests take you? Where did you teach?

Biondi: I was an adjunct instructor for eight years while I was in graduate school at Bowling Green State University. I began my full-time teaching career at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, where I was an assistant professor for four years on a tenure track. I left for a job at Marymount Manhattan College, where I taught for thirteen years. I was an assistant professor of philosophy, and about ten years ago I earned tenure and got promoted to associate professor of philosophy. During my last six years there, I served as the department chair of philosophy and religious studies.

Hersey: I know you worked hard to get there. What soured your love for the job and convinced you to give all that up?

Biondi: I think there were two causes that ultimately led me out of higher ed. One was epistemological, and the other was political.

So, first the epistemological point: I came to realize that I was spending at least 50 percent of my time helping students unlearn all their bad habits from before college. Many of them didn’t know how to learn. Many were terrified to think independently, and they really didn’t know why they were in college.

Some thought they were good students because they had gotten all A’s in high school. But they got all A’s by memorizing and regurgitating information that they were told to memorize. And that was not going to cut it for college-level courses, especially not in philosophy, where one of the most fundamental questions is: Why do you believe that? What are your reasons? There were lots of tears over the years, but some students were willing to work hard to break through. They unlearned bad habits and became motivated to learn how to think, to reason, to argue, to write.

A question I heard repeatedly over the years was, “Oh, my goodness! How come I never learned to do this when I was younger?” I often heard things like, “I feel like I have to start all over again!” Now that they knew how to think independently—had gained the courage and skills to do it—they’d say, “I wish I had been doing this for years so I could be doing even more of what I enjoy today, and at a higher level.”

I likewise wondered why they hadn’t learned to think independently earlier in their lives, and I came to realize that it’s because most students come through government schools, which reward teachers for pushing people through standardized tests and calling that education, though it’s not. So, a big part of the draw for me getting out of academia was to be part of the solution, to help address some of those underlying epistemological problems that left students unprepared to learn at a high level.

My shift in this direction was accelerated beginning in 2016. Although academia always had a bit of a political undercurrent, especially in large urban colleges, I think most were still largely devoted to education. Students were seeking an education, and faculty were there to provide it.

But after the 2016 election, things became highly politicized at Marymount Manhattan, where I was then teaching. Throughout my career, there had always been a small percentage of faculty and students who wanted to politicize the classroom, to make it less about learning and more about political activism. But after the election, many students and faculty flipped out. That’s the only way I can think to describe it; they became deranged, politically, and wanted to push to a much wider agenda.

I’m not merely talking about some of the more radical Marxist-oriented professors. A lot more students wanted other professors—who were not seeking to politicize their classrooms—to make political activism part of their projects. And that’s something I resisted. They thought that they weren’t really learning something unless they could use it for social or political activism. They wanted course credit for activism-related projects in lieu of actual academic projects related to courses. A question I started hearing increasingly was, “How is this course relevant to what’s going on today?” If we were studying ancient Greek philosophy, and we were learning about the pre-Socratics, students would want to know, “How is this relevant to fighting for social justice?” In essence, they wanted to be fed what to say to win a particular political debate, to learn talking points that would help them take down opponents. And many students thought that pushing back on course material with questions like that would get me to change the course.

My response, in effect, was, I’m here to educate, not indoctrinate. You don’t need to know where I stand on certain issues. I’m not here to help you learn what to think but how to think for yourself about anything. You can hold your own political views, and you can come to whatever conclusions you see fit. But my classes are not to be politicized. Students, however, pushed more and more toward more indoctrination, which I deeply opposed.

Well, come 2020, the week of the riots after George Floyd’s death, everything changed. The college administration became overtly political. They crossed the line, traipsing on academic freedom. They said, in effect, “We’re going to vet your syllabi to make sure that certain viewpoints are embodied in them.” These viewpoints were highly political and highly controversial, and I was not going to be party to that. So, I knew it was time for me to leave academia. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I realized that I was not going to be able to pursue the values that, for twenty-five years, I had worked toward. I wouldn’t be able to cultivate independent thinking in my classrooms.

So, you can see there were those two strands: the epistemological problem and the political one.

Hersey: Your ancient Greek philosophy students must have appreciated the Sophists at least, no?

Biondi: Ha! I brought up that course in particular because I thought it was ironic that many students—because they weren’t paying attention to the ideas—didn’t grasp that they were engaging in a sophistic endeavor. Learning the Sophists’ tactics and arguments may actually have served their aims, but most didn’t make the connection because they weren’t interested in engaging with the reading and learning to think for themselves.

If they had, they would have understood that they were advocating a view very similar to the Sophists and that this sort of debate is very old. And they may have realized that they need to think a lot harder and more carefully about whether their aims were good ones to pursue.

Hersey: What were some of the initial ways the campus became politicized?

Biondi: Students—and sometimes faculty—would plan walkouts for political reasons. Instead of teaching their classes, faculty would cancel them in order to go support a particular political agenda. They expected it would be OK for them to be absent or to not be held to their teaching contracts because they were taking a particular political stance. But I don’t believe that the college would have extended the same leniency for those with opposing views.

Hersey: Do you recall what stances people organized walkouts in support of?

Biondi: Gun policy, for one. Climate change policy, for another. Students and faculty thought they should be excused from class (or work) to go downtown and attend, say, a climate change protest, or to walk through the streets to protest gun ownership. If people would have walked out or canceled class to support Second Amendment freedom, that would not have been OK.

Hersey: We’re not talking about one teacher canceling a class on climate science to go down to a climate rally and hear opinions on science-related topics, right?

Biondi: Administrators would send e-mails encouraging faculty to excuse student absences. Dozens of faculty would take their classes down to a rally, and it certainly was not for educational purposes—it was to engage in activism.

Hersey: Were you ever pressured to take part, or to encourage your students to do so?

Biondi: Yes, I’d have arguments with faculty in the hallways, over e-mail, and at our faculty council. I often pointed out that this was not the purpose of an educational institution. Faculty should support students to engage in educational events, not ones promoting a particular political stance.

Some faculty and administrators didn’t like that I and a few other professors who agreed with me held our students to the absence policies stated on our syllabi. They’d say, “You need to understand that this is part of their educational experience.” But I was not going to let students exceed their allotted number of absences to skip class and go to a political protest. You get two absences per semester, and you may use them for any reason you choose. You might be sick, you might be studying for an exam—who knows. To me, it doesn’t matter. But when you use those absences, that’s it. I don’t privilege certain activities over others and let a student have more than what everybody else is permitted just because he or she wants to go voice a certain political opinion.

I got a significant amount of pushback on this from some faculty and, increasingly, from students who expected activism to substitute for educational experience.

Hersey: Were you ever pressured to take part in an event, to leave your class and go to a climate change or a gun control rally, or the like?

Biondi: Not while I was at Marymount Manhattan College. When I was an assistant professor at John Jay College prior to that, they had a teachers’ union, and I was definitely pressured to participate in rallies and protests that the CUNY system teachers’ union supported. I always refused. They would leave picket signs outside my office door, expecting me to relent and join them at political rallies, but I never did.

Hersey: Do you think your refusals impacted your career trajectory at all?

Biondi: Perhaps at John Jay College, but not anything I could prove. I just know that some of my colleagues were not happy that I would not participate. Fortunately, Marymount Manhattan College did not have a teachers’ union to exert political pressure.

Hersey: What role do teachers’ unions play in the broader politicization of universities?

Biondi: Well, thankfully, I had to participate in a union for only four years. But from my experience—and from what I’ve researched and heard from other college professors—teachers’ unions play a huge role in politicizing campuses. They use teachers’ union dues to engage in political activism and to leverage bargaining positions with the administration.

They always pit the faculty against the administration and threaten teacher walkouts if their demands are not met. They know that parents don’t want faculty walking out on their students when they’re paying all that tuition. So, they threaten walkouts as a bargaining chip.

They would also use the union dues to support various political positions. For instance, when I was at John Jay College, they lobbied the state of New York or the city of New York to spend more tax dollars on higher ed. If I recall correctly, they also lobbied for student debt forgiveness, which I deeply oppose.

I thought it was immoral for them to take my money and use it for political causes, especially ones I disagreed with. But it was a condition of employment that I be part of the teachers’ union.

So, yes. Teachers’ unions definitely instigate the politicization of campuses.

Hersey: Do you know what Marymount Manhattan College was looking for with the plan to vet teachers’ syllabi?

Biondi: They expected even nonpolitical courses to serve a political agenda. One phrase that stands out in my memory was their aim to “de-center a Eurocentric curriculum.” All faculty were expected to meet a certain quota of “diversity,” according to their conception of “diversity.”

I had an incredible diversity of ideas in my courses. No matter what topic I taught, I always presented a range of clashing perspectives. Most of the ideas I presented or had my students read, I personally didn’t agree with. Agreement with the ideas in the material one teaches is largely irrelevant to teaching well, as far as I’m concerned. So, my students would encounter a wide variety of ideas. We would give them a full-throated, fair hearing, and I expected students to come to their own conclusions about whether these positions were good or bad and had strong or weak evidence in support of them.

But this isn’t what the administration meant by “diversity.” It was not about diversity of ideas, but “diversity” according to some politicized benchmarks: “Do I have any women represented on my syllabus? Do I have any historically disadvantaged groups represented on my syllabus?” I never submitted a syllabus to be vetted under the new criteria because I decided to leave. But I gather that the syllabi I’d been honing for years would have been rejected.

Hersey: You mentioned Marxist professors. Presumably, they run the gamut, but do you have any experience with their syllabi? Was their teaching likewise ideologically diverse?

Biondi: Some such faculty are very fair-minded, and their syllabi reflect a range of views. But there were certainly a lot of professors—increasingly, especially over the last five to eight years—who deliberately would not include canonical works.

Take literary criticism, for instance. They would omit canonical works and standard approaches and would focus instead almost exclusively on, say, post-structuralism, feminism, queer studies, or postmodernism. Leaving out certain approaches because you reject them, and including only perspectives you happen to agree with—I think that’s where teaching crosses the line into indoctrination.

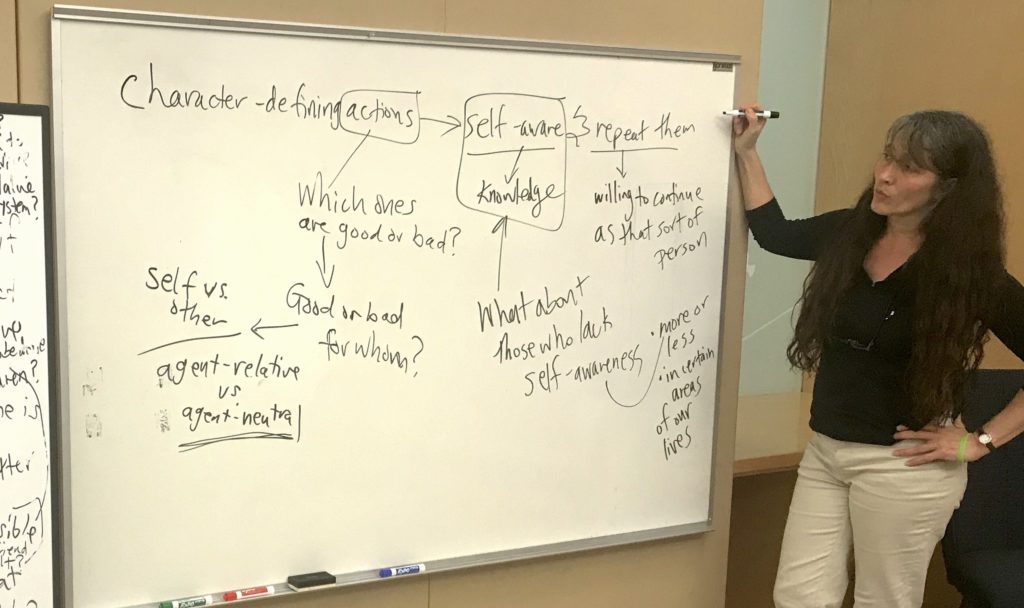

Many faculty considered critical thinking to be synonymous with critical theory, which is critiquing canonical views—and, in their view, you’re not really critiquing something unless you’re taking an outsider or marginalized perspective on the topic. But that is not critical thinking. It’s equating independent thinking with adopting particular feminist or environmentalist or postmodernist perspectives. That conflation is deeply misleading and pernicious.

One key component of critical theory is that there is no objective reality. There are only subjective human experiences, and these competing narratives vie for power. And when you believe this, everything becomes a power grab. Instead of taking a principled stand to find out what’s true and to do what is objectively good, objectivity is out the window. Seeking to do what’s right is out the window. Everything boils down to a Machiavellian power grab. On this view, presenting alternative views in your classroom is a cession of power.

Hersey: What impact, if any, did the victimhood mentality have in your classes, or your experience with higher ed in general?

Biondi: I certainly did hear a lot of students, particularly when the #MeToo movement was afoot, voice concerns about “microaggressions.” They expected “trigger warnings” about certain issues. For example, in my ethics of law and business ethics courses, I would sometimes teach the topic of pornography and law, or free speech, or “hate speech.” Some students would say, “I don’t feel comfortable discussing this in class. This is triggering me. I need to leave class.”

In the last few years, an increasing number of students wanted to censor what things can be discussed in class or to be given a pass on certain types of assignments, claiming something offended them. This would really chill class discussions.

Now I would never tolerate people being uncivil to one another, lobbing ad hominems or name calling. But many would not allow for what, in the philosophy of language, is called the use-mention distinction. For example, we might be reading an article that uses the language “whores and pimps,” or something like that. Increasingly, a student might say, “I'm triggered by being called a whore.” But no one was calling anyone a whore. It was merely written in the article. I’d point out, “I’m mentioning this because it’s used here. So, if that’s making you uncomfortable, and you feel like you need to be excused from class, then do you want to take that as one of your two allowed absences? That’s your business, but you’re not going to get a special pass just because you feel offended or upset by that.” This sort of self-victimization definitely was ramping up a lot in the last few years of my teaching.

Hersey: More and more teachers are leaving the profession for reasons related to academic freedom and forced orthodoxy on social and political issues. Peter Boghossian has just very publicly left Portland State University for such reasons. Do you think this problem with the universities can be solved, especially given that those perhaps best placed to solve it are shrugging off academia and leaving? Or do you think that the universities are lost, and there is no hope for saving them?

Biondi: I think that good people who are devoted to real education and not indoctrination could create alternative private universities and colleges. These would be oases in the higher-ed desert.

However, I think that in the larger context of higher ed, these oases are going to be at a massive disadvantage because they’re facing Goliath. The vast majority of higher education is funded by government dollars. So long as tax monies are supporting publicly funded universities—which significantly subsidize the vast majority of students and pay much higher salaries for faculty and administration—it will be very difficult for genuine alternatives to compete in the higher-ed market.

I think that one of two things would have to happen in order for higher ed to be rescued from the indoctrination problem. The first is to pull government money out of higher ed. That would go a long way. The other thing is that if enough parents refuse to send their children to these institutions—if they just say, “You know what, my kids don’t need to go to college because they can achieve their learning and have lives of meaning and purpose and value other ways, and we’re not paying for this malarkey”—that would also go a long way.

So, I think that those two things, one or both, would have to happen for higher ed to basically collapse. Otherwise, I don’t see this entrenched structure changing.

Hersey: You mentioned earlier that you were asking yourself, “How can I do more to teach students the skills of independent thinking?” Is what you’re doing now related to that?

Biondi: Yes, I now develop humanities curricula for a Montessori high school system. The Montessori method of learning is oriented toward students learning inductively from the world. Teachers are not called teachers; they’re called guides.

I develop humanities curricula for the high-school level that is Montessori-aligned in pedagogy. My focus now is helping students learn how to learn—helping them become lifelong learners. We develop curricula such that, when a student makes a mistake, he’s corrected by the information he’s getting from the world around him, not from other human beings telling him what to believe or trying to motivate him with grades. We support students in pursuing what they love. But we do it in a rigorous and structured way that helps them achieve intellectual independence, so that when they become older—whether they choose to go to college, open their own business, invent something, or whatever it is that they want to do with their wonderful lives—they are equipped. They have the courage and the intellectual tools to pursue their dreams and continue learning for the rest of their lives. So, that’s what I’ve turned my energies toward, and I’m very glad to be part of that solution.

Hersey: Well, thank you for your efforts in higher ed and, now, for helping to equip young people with the ideas and tools they’ll need to lead flourishing, successful lives.

Biondi: Thank you, Jon.

Click To Tweet