The longtime Democratic operative James Carville gives good quote, and yesterday was no different. In a conversation with Vox about Biden’s first 100 days he ended up mostly sounding off about the problem of what he calls “faculty lounge” politics:

You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like “Latinx” that no one else uses. Or they use a phrase like “communities of color.” I don’t know anyone who speaks like that. I don’t know anyone who lives in a “community of color.” I know lots of white and Black and brown people and they all live in . . . neighborhoods.

If you have a few minutes, read the whole thing. But Carville’s bottom line is that “there’s too much jargon and there’s too much esoterica and it turns people off.”

One bit of that jargon — much like “equity” and “social justice” — is the phrase “systemic racism.”

All of a sudden, it was everywhere. We were supposed to say it. We were supposed to root it out. But what did it actually mean?

Is systemic racism merely legal discrimination? Or does it capture the legacy of slavery and segregation? Is it meant to describe ill-conceived policies, like the response to the crack epidemic? Or is it something far more expansive, sweeping up any kind of racial disparity as evidence of its existence?

We are talking past one another. Perhaps that’s because people are scared to admit ignorance. Perhaps that’s because those who use the phrase mean for it to be elastic. Mostly I suspect it’s because no one wants to seem like they are in anyway denying racism’s evil by asking any questions about it at all.

It seems to me that these are exactly the reasons why we need to discuss this morally freighted and confusing phrase.

So today I invited a group of writers I admire and who challenge me to weigh in on the question: What is systemic racism?

The Foundation of America Itself

By Lara Bazelon

Let me tell you about how the criminal justice system operates in the state of Louisiana. Forget the Fourteenth Amendment that guarantees everyone the right to due process and equal protection. In this state, a "habitual offender" law allows prosecutors to double the maximum sentence of anyone convicted of a felony if they have a prior felony on their record.

Leon Cannizzaro, who was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish from 2009-2020, invoked it more than 3,000 times, overwhelmingly against Black people, many of them teenagers. As the state’s sole Black justice explained dissenting from one of these decisions, the statute was a modern-day version of the “Pigs Laws” enacted during Reconstruction and “designed to re-enslave African Americans.”

That law re-enslaved my African-American client.

At the age of 19, he was subjected to a pretextual stop. He was wearing a gray hoodie and dark jeans, which to the arresting officers meant he “matched” the description of a suspect in an armed robbery, which had occurred nearby and nearly a full day earlier. The suspect was described as slim-built and dark-complected; my client, at 5’8,” weighed 185 lbs, and he was light-complected with a moustache and beard. None of that mattered. A white man had been robbed at gunpoint of $102 dollars and my client, when the arresting officer tackled him, had a gun.

The trial took less than one afternoon.

The victim was not hurt and the crime itself lasted less than two minutes. Nevertheless, the state invoked the habitual offender law. My client’s sole prior was a drug sales conviction at the age of 17. He was an honors student, a star athlete, a warm and generous person who had survived open heart surgery from cancer. Today, that case would be handled in juvenile court.

The judge gave him 60 years in prison with no possibility of parole.

At the prison, my client was sent out to work in the fields every day picking crops with the other able-bodied prisoners, nearly all of them Black. The guards who oversaw them on horseback formed a gun line. If anyone crossed the line, they got shot.

“Every day I was out there,” my client told me, “I would think about running the gun line before I let these people break me and just get it over with.”

My client was convicted in 2013. But it might as well have been 1813.

When the robbery occurred, my client was eight miles away. A witness would have said so. The hotel surveillance footage would have proved it, along with his cell phone records. In desperate calls from jail, my client pleaded with his lawyers to get this evidence. “It will clear me,” he said. The prosecutors listened to all of those calls—they knew and didn’t care. Neither did his lawyers. The jury never heard his alibi.

My client’s case is not an anomaly. Neither is the system in Louisiana. Our legal system is based on indifference and animus toward Black lives, fueled by cruelty so casual that it is depraved, and white supremacy so systemic that it is foundational.

Lara is a professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law where she directs the criminal and racial justice clinics. Her first novel, A Good Mother, will be published next month.

It Obscures Problems and Prevents True Progress

By Kmele Foster

Before the turbulent summer of 2020, you were far more likely to encounter the words “systemic racism” in a scholarly journal than in a primetime presidential address. Now you can’t get through an Oscar speech or a corporate tweet without tripping over it.

But it's hardly clear that Americans share an understanding of just what the phrase means or how easily it can undermine our ability to better understand and address enormous societal challenges.

When invoked by activists or academics, the concept is deceptively matter-of-fact. If America’s laws and institutions tend to generate racially disparate outcomes, then, irrespective of intent, the country is “systemically racist.” This definition makes it easy to fold everything from the impact of Covid-19 to police-involved killings to standardized testing into the same politically charged and counterproductive framework.

Each of these issues has been contaminated by racial politics, but perhaps none more so than education.

In New York and San Francisco, concerns over “systemic racism” have led lawmakers to largely abandon their responsibility to actually fix chronically failing schools. What have they done instead? Degraded admissions standards for their best-performing magnet programs because there were too many Asian and white students. Launched campaigns to rename schools deemed to have offensive names. And, most disturbing of all, they’ve committed themselves to making public school campuses ideological battlegrounds —condemning the very idea of merit and insisting that black students should not be held to the same standards as their white peers.

It’s a perverse ratcheting down of expectations and a reflection of an ideological program more concerned with racial parity than meaningful progress.

Kmele is co-host of the podcast The Fifth Column.

The Most Nettlesome Term in the English Language

By John McWhorter

Systemic racism — or its alternate term, institutional racism — became common coin as a designation in the late 1960s, just as the expression of overt personal prejudice was increasingly proscribed and such prejudice itself waned ever more, leaving behind subtler kinds of bias less easily addressed. The idea behind the phrase is that inequities between whites and blacks on the societal level, such as in scholastic achievement, wages, wealth, quality of housing and health outcomes, are due to racist bias of some kind, exercising its influence in abstract but decisive ways. As such, the existence of these inequities represent a sort of “racism” that must be battled with the same urgency and even indignation that personal “prejudice” requires.

The problem is that sociology and social history are more complex than this interpretation of “systemic racism” allows. All race-based inequities are not due to “prejudice.” Moreover, all race-based inequities do not lend themselves to the kind of solutions that eliminating “prejudice” do. For example, to attribute black students’ lesser performance on standardized tests to “racism” is an extremely fragile proposition. To simply eliminate the tests as “racist” because black students underperform on them is an anti-intellectual and even destructive idea.

I find the term “systemic racism” to be the most nettlesome term in the English language at present.

John teaches linguistics at Columbia University. Follow his writing here.

A Bluff and a Bludgeon

By Glenn Loury

The invocation of “systemic racism” in political arguments is both a bluff and a bludgeon.

When a person says, for example, “over-representation of black Americans in prison in the United States is due to systemic racism,” he is daring the listener to say: “No. It’s really because there are so many blacks who are breaking the laws.” And who would risk responding that way these days? The phrase effectively bullies the listener into silence.

Users of the phrase seldom offer any evidence beyond citing a fact about racial disparity while asserting shadowy structural causes that are never fully specified. We are all simply supposed to know how “systemic racism,” abetted by “white privilege” and furthered by “white supremacy,” conspire to leave blacks lagging behind.

American history is rather more subtle and more interesting. Such disparities have multiple, interacting causes, ranging from culture to politics to economics and, yes, to nefarious doings of institutions and individuals who may well have been racist. But acknowledging this complexity is too much nuance for those alleging “systemic racism.”

They ignore the following truth: that America has basically achieved equal opportunity in terms of race. We have chased away the Jim Crow bugaboo, not just with laws but also by widespread social customs, practices, and norms. When Democrats call a Georgia voter integrity law a resurgence of Jim Crow, it is nothing more than a lie. Everybody knows there is no real Jim Crow to be found anywhere in America.

The phrase also does a grave disservice to blacks and to the country. Here we are now, well into the 21st century. (Have you heard of China?) Our lives are being remade every decade by technology, globalization, communication, and innovation, and yet all we seem to hear about is race.

My deep suspicion is that these charges of “systemic racism” have proliferated and grown so hysterical because black people — with full citizenship and equal opportunity in the most dynamic country on Earth — are failing to measure up. Violent crime is one dimension of this. The disorder and chaos in our family lives is another. Denouncing “systemic racism” and invoking “white supremacy,” and shouting “black lives matter,” while 8,000 black homicides a year go unmentioned — these are maneuvers of avoidance and blame-shifting.

The irony is that so many of us decry “systemic racism,” even as we simultaneously demand that this very same “system” deliver us.

Glenn is the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences and Professor of Economics at Brown University and host of The Glenn Show.

Institutional Collusion Against Asian-Americans

By Kenny Xu

If you are going to lodge the explosive charge of systemic racism, the burden is on you to assert the who: who is denying equal opportunity to a racial group?

“Society” or “America” are insufficient answers. But saying: “The U.S. government, particularly the Southern States, denied equal opportunity in voting rights to African Americans during the period of Jim Crow,” meets the burden of proof. There is abundant evidence that Southern States colluded with each other to suppress African-American voting rights during this period.

Systemic racism requires institutional collusion.

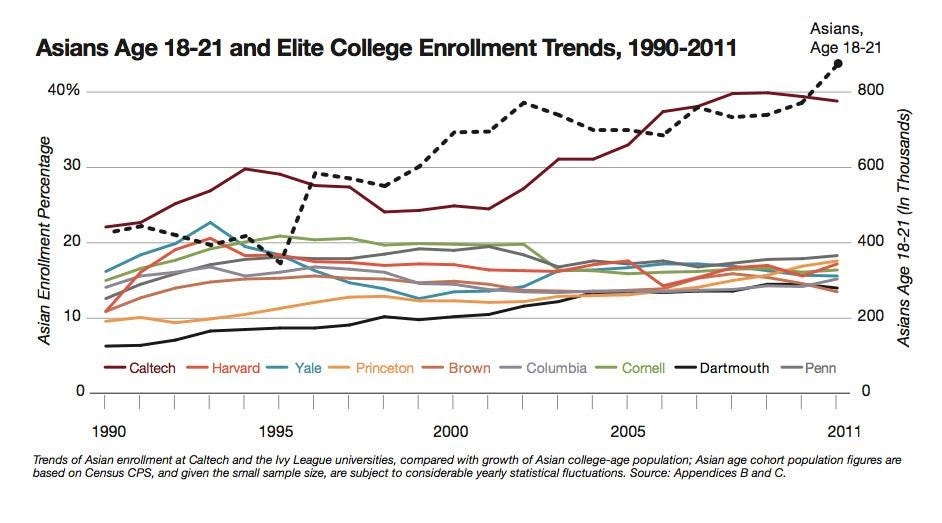

Systemic racism is being carried out today in America’s elite university system against Asian-Americans. The Ivy League (and other selective schools like MIT and Stanford) currently coordinate to deny Asian-Americans equal opportunity in the admissions process based on their race.

Consider the graph below. This graph shows Asian-Americans being held nearly constant over the course of two decades in all Ivy League schools even as average Asian-American SAT scores have gone up. Meantime, the one school in the graph that does not practice race preferences, Caltech, shows increasing Asian-American admission. Asian-Americans are kept to an astonishing 15-20 percent of the Ivy League student body with almost no variance despite Harvard’s own internal reviews suggesting Asians should be at least 40 percent of the student body if race preferences were removed. Indeed, Harvard gives Asians applicants low “personality” scores in order to lower their chances of being admitted.

The central tenet of the American dream is captured in the 14th amendment of the constitution: the state will not “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” No American deserves to be denied based on his background or the color of her skin. All Americans deserve to be treated on the basis of individual merit alone.

Kenny is the author of “An Inconvenient Minority: The Attack on Asian American Excellence and the Fight for Meritocracy,” forthcoming in July.

The Limits of a Metaphor

By Chloé Valdary

Slavery was America’s original version of systemic racism: the dehumanization and enslavement of African Americans because of their color.

Jim Crow was another: the disenfranchisement by law of black Americans because of their skin. Jim Crow laws in the South meant, for example, that not only was it legal to discriminate against black Americans, but that it was also illegal to treat them humanely. Prejudice was mandatory. Segregation, public humiliations, and lynchings were encouraged by the political establishment whose social anxieties and deep-seated insecurities required the systematic degradation of others. It was, quite literally, systemic.

But it is useless to know this gruesome history if we fail to understand the maddening psychological disposition that made this reality possible. James Baldwin frequently pointed out that the mistreatment of black Americans was driven by white Americans’ fears of their own lives and the projection of those fears onto others who did not look like them. Baldwin called this a “joyless” and “schizophrenic” reality, one in which many white Americans, having lost the capacity to feel, could no longer trust themselves or perceive their own worthiness. Spiritual desiccation had taken over American life and this poverty drove white citizens to overcompensate by beating and murdering those who were different from them.

Perhaps for this reason alone, it is worth considering the limitations in using the metaphor of a mechanical “system” to describe racism, since racism becomes more likely when we are cold and mechanical, machine-like, numb to the conundrum of our own lives and those around us. If we want to combat the scourge of prejudice, we ought to commit to reversing this process, and take responsibility for the beauty of our own lives, both its tragedies and its joys.

Chloé is the founder of Theory of Enchantment.

I used to regularly put together roundtables like this when I was an editor at The Wall Street Journal. I think they can bring a lot of light to overheated conversations and I’m thinking of doing more along these lines if you like the format. Let me know in the comments.

And if you haven’t subscribed . . .