There is a single, powerful moment in Manuel Oliver’s stage show that captures the purpose of a work he never wanted to write. An alarm clock rings, signalling that 15 minutes have passed since the last life was lost to gun violence in America, and that another person is about to die. He hurls the clock across the set and it explodes into a mass of springs and metal, filling the theatre with a haunting silence.

Oliver’s anger is directed as much at the grim statistic that 100 people die every day in the US from gunshot wounds as at the death of his own teenage son, Joaquin, in the Parkland high school shooting massacre of 2018.

Turning the loss of his best friend, the 17-year-old he calls Guac, into a compelling one-man stage performance, has been difficult and emotionally draining, Oliver says. But it’s something he insists Joaquin would have wanted him to do. It is his way of raising awareness of gun violence issues and building on the “art activism” he and his wife, Patricia, have conducted through painting murals and their not-for-profit advocacy group Change the Ref, since 17 students and staff were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school.

“This play is not for people to feel bad for me or Patricia,” he said. “It’s about feeling sad for themselves or their kids because they could end up being who we are.

“You don’t know when we finish this interview we’re going to be able to speak again tomorrow. So we thought, ‘How do we get closer to people, how do we use our skills to have an intimate conversation with people instead of having to beg for their attention, or be more effective with the attention they give us?’

“It brings me to the idea that everybody should listen, anybody who is part of this social gun culture atmosphere that has been happening for years. My whole life I was training for something I had no idea what it would be. I think it’s this play.”

Oliver will perform Guac: My Son, My Hero, on Friday night at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, the first date of a Live Nation-sponsored national tour that will run through 2020, often in cities blighted by gun violence or which have suffered their own mass shootings, among them Orlando, Chicago, New Orleans and Houston.

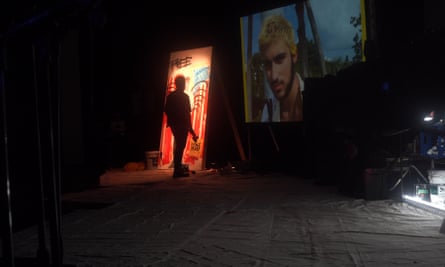

In “an immersive emotional experience that inspires audiences to take a stand on gun violence”, Oliver uses live painting, audio and visual presentations and monologue to tell the story of Joaquin’s upbringing and his family’s lives in their picture-perfect south Florida community, before and after the shooting.

Its most impactful scene is unquestionably the one in which Oliver, wearing a mask of Joaquin’s face, re-enacts the Parkland shooting through the eyes of his son. He conveys the same chilling terror experienced by students at Saugus high school in Santa Clarita, California, as recently as last Thursday.

But there are lighter moments, too, a recognition that this is after all a production that must weave threads of entertainment through the darker seams of gun violence and the murder of a child.

“We own this story, and that’s sad,” Oliver said. “Usually when you hear people say they own a story it’s a good thing, but nobody wants to own this one. So when you own it, and you’re not an actor, you find your story is missing something. You start adding stuff you just remember, like, ‘Wait a minute, we were in New York with Joaquin several times, there’s things a New York audience will appreciate.’

“We were lucky to travel with Joaquin, there’s a lot of stories, a lot of memories to share, baseball, basketball, swimming, parties, games, everything. So that brings a lot of content when we need to talk about our son.”

Oliver co-wrote his play with James Clements, a Scottish-born writer, director and producer with a wealth of Broadway experience. The two were introduced by the Tony-winning producer Yael Silver, the show’s executive producer.

“It’s his true story, it’s his voice and his energy,” Clements said. “The weight of the story is all there, the heaviness, the love and the tragedy are all there. My role is finding the joy. Joaquin and his family shared those wonderful 17 years and his spirit is truly living on in the actions of his parents.

“What happened doesn’t define the lives of Manuel and Patricia, Joaquin or his sister Andrea, it’s the little things that make a family, it’s hot dogs and movies, basketball, Family Guy and Frank Ocean.

“We can surprise the audience with this lightness, this warmth and beauty of the family they built and the magic moments they created. It makes the show all the more impactful.”

Joaquin’s parents differ over how much of a healing process the play has been. Patricia Oliver said poring over old photographs and videos of her “sweet, dreamy son” was at least in part cathartic.

“I’d rather remember Joaquin happy because that was him, this happy, funny, silly, demanding kid,” she said. “When I see the videos, it’s nostalgic and sad but I see him happy and that makes me happy.”

Her husband avoids memories of Joaquin “if I don’t have a reason to do it”.

He said: “I’m able to go over any image, or video of Joaquin, any sound or whatever, as long as I’m making a statement, as long as I’m using that as part of a movement that’s going to create some change or awareness in our society. That’s how I’m able to do that on stage.”

Ultimately, persuading audiences to take action is the primary motivation.

“Once the play is over,” he said, “and you have all those emotions hot, you see in the lobby, before you even leave the building, a booth with March for Our Lives, another asking you to register to vote, another selling a T-shirt, another Gays Against Guns. You have many options, there’s no excuse not to do something.

“If I’d had that chance before 14 February maybe I would get the message, maybe I would take action, maybe I would have been able to save Joaquin. That’s why I want everyone to see this. You can be in the same position as us, and the question is, what are you going to do about that?”

Guac: My Son, My Hero, is at the 92nd Street Y in New York on 22 November at 8pm