Last spring, a group of farmers, historic preservationists, and law students worked together to keep a granite mine from chipping away at the health of a small Georgia community.

Words and Photographs by Krishna Sharma

October 19, 2021

It’s mid-March, and Johnny Thornton greets me outside his catfish farm in Mayfield, Georgia. The chain-link fence opens with a wail as we step onto his historic property in Hancock County, nestled on the banks of the Ogeechee River. After the farm had lain defunct for decades, Thornton purchased and began renovating it in 2011. While the site boasts 25 outdoor ponds for raising catfish, only a couple are currently in use. Pine forest once stood across from Thornton’s farm until Mayfield Natural Resources, LLC, cleared it in anticipation of a new, 500-acre granite quarry. The quarry, which would be situated in a county that is 71% African American — a county that CNN has described as one of the Blackest in the nation — is vehemently resisted by locals. With three other quarries already in Hancock County, residents are worried about increased silica dust, disruption of waterways, and damage from blasting so close to farms, historic sites and homes.

Another rock quarry may sound like a humdrum affair, but the effects can be disastrous.

First, there’s the dust. In the rock-mining process, silica rubs off in clouds and drifts off. Inhalation of that silica dust by workers over several years can cause silicosis, an incurable lung disease. Even though that disease is usually confined to the work environment, and few studies have examined how drifting dust may affect nearby properties, locals still worry about breathing that dust in.

Then there’s the water. To mine granite, that silver-gray belly of the Earth, water is often pumped from the ground to be used with a high-pressure water jet. The disruption of underground water systems can dry up local wells that rural residents rely on. While plenty of quarries operate without jeopardizing the local water supply, the uncertain threat of it was enough for Ringwood, New Jersey, to deny a license renewal for a nearby quarry in 2020.

Finally, there’s the blasting. Getting rock means cracking it with explosives. The most obvious repercussion is incessant noise pollution, but the blasts themselves can dangerously shake nearby houses to the point of cracking walls and windows. To be sure, there are laws requiring mining companies to limit the size and frequency of blasts, but residents are still worried about worst-case scenarios.

Mayfield Natural Resources, LLC, would not shed light on the details of its operations or how it planned to address the concerns of residents, says Thornton. In light of these fears, Thornton and others in the local community self-organized into a powerful grassroots movement, so grassroots it does not even have a name.

Johnny Thornton at his catfish farm in Mayfield, Georgia. The pond behind him is one of two that currently hold catfish. Thornton has put immense effort into renovating the property and is trying to bring jobs and revenue to the local community.

To understand this grassroots movement, you must contextualize it in the county’s rich yet neglected history.

“Hancock, now one of the nation’s poorest counties, was once a leader in the antebellum South,” wrote John Rozier in his 1982 book Black Boss: Political Revolution in a Georgia County. After visiting Hancock County in the late 1930s, a CBS commentator said over the air that it was a “lynch-proof” county, a place where both African Americans and white Americans pursued scientific farming, education, and wealth.

When the economy dried up, however, that all changed. And in 1966, driving a beat-up old Chrysler, a man who would forever reshape the rural South arrived in Hancock. The “Black Jesus” of middle Georgia: John McCown.

Like grasping for worms in the mud, the realities of John McCown seem to wriggle away from modern hands. He rose as a civil rights activist, successfully leading a march to desegregate the Hancock County school system, among numerous other feats. In 1968, McCown was elected county commissioner and, with popular local support, helped make Hancock the first county in America since the days of Reconstruction to have a predominantly Black political power structure.

He was a maverick and a man of fire. Amid political and racial tensions, McCown was still able to secure a massive financial legacy for Hancock. Throughout the 1970s, he received grants from the Federal Office of Economic Opportunity, the Ford Foundation, and others to funnel millions of dollars into the county.

The East Central Committee for Opportunity’s catfish farm, which once held 7,000 pounds of catfish, was part of McCown’s grand entrepreneurial vision. In 1971 Time magazine called it one of the largest and most scientific catfish farms in the world, and McCown planned to bring in massive annual revenue by selling fresh and frozen catfish to eager restaurants. With federal dollars streaming through Hancock like the Ogeechee River itself, the stage was set for Black sovereignty to lead Black prosperity in rural America.

Yet controversy sprouted beneath every step McCown took, and he was not shy in provoking it. And despite McCown’s iron fist full of money, the county always stayed poor. One inauspicious day, just a few years after the farm’s construction, its ponds looked as sickly green and thick as swampland. The catfish, and the dream they represented, died in algal sludge. In his book, Rozier wrote about rumors that the catfish had been poisoned by agitated white community members who were tired of McCown’s racially charged rule. But other folks, including a Black farmer who helped manage the catfish farm for 13 months, claimed that it was McCown’s poor business management skills that led to belly-up catfish.

“He was the greatest community organizer and worst businessman I knew,” said one local, in Rozier’s book. A later federal investigation found that his employee turnover rate was massive due to poor record keeping and a lack of supervision. These administrative problems financially sank McCown’s other Hancock projects, too, including a new hospital and a public housing complex.

Fast-forward to 2021 and Hancock ranks among the poorest counties in the nation. Moreover, its 9,000-person population has been fighting voter suppression. In many ways, Hancock County’s race relations today remain as murky as the water that suffocated the catfish.

Thornton, a former DEA agent who grew up in Henry County, Georgia, accidentally stumbled onto the catfish farm while on a hunting trip. Enticed by the idea of farming catfish, something he had never done before, he purchased the property and embarked on a new lifestyle. His goal was to maintain McCown’s dream: using the farm as a vehicle of economic improvement for the local community.

As we tour the ponds behind his office, Thornton shares that he thinks some members of the white community still resent the farm for its contentious history of Black empowerment, and in turn resent him for owning it.

However, Thornton emphasizes that this is about a grassroots movement in a culturally rich community rather than about race politics. “If there’s one thing I want people to understand,” Thornton says, “it’s that this is a community issue. I don’t want people to think this is just happening to some poor Black man in rural Georgia. It’s about the whole community.” Whether rich or poor, white or Black, man or woman, a whole community is uniting against the quarry.

To appreciate the vibrancy of the movement, we drive over to visit other property owners uniting with Thornton as they prepare for an upcoming hearing about the quarry site. Their single goal: get the Hancock County commissioners to vote no.

The house behind which Hancock County activist John McCown is buried.

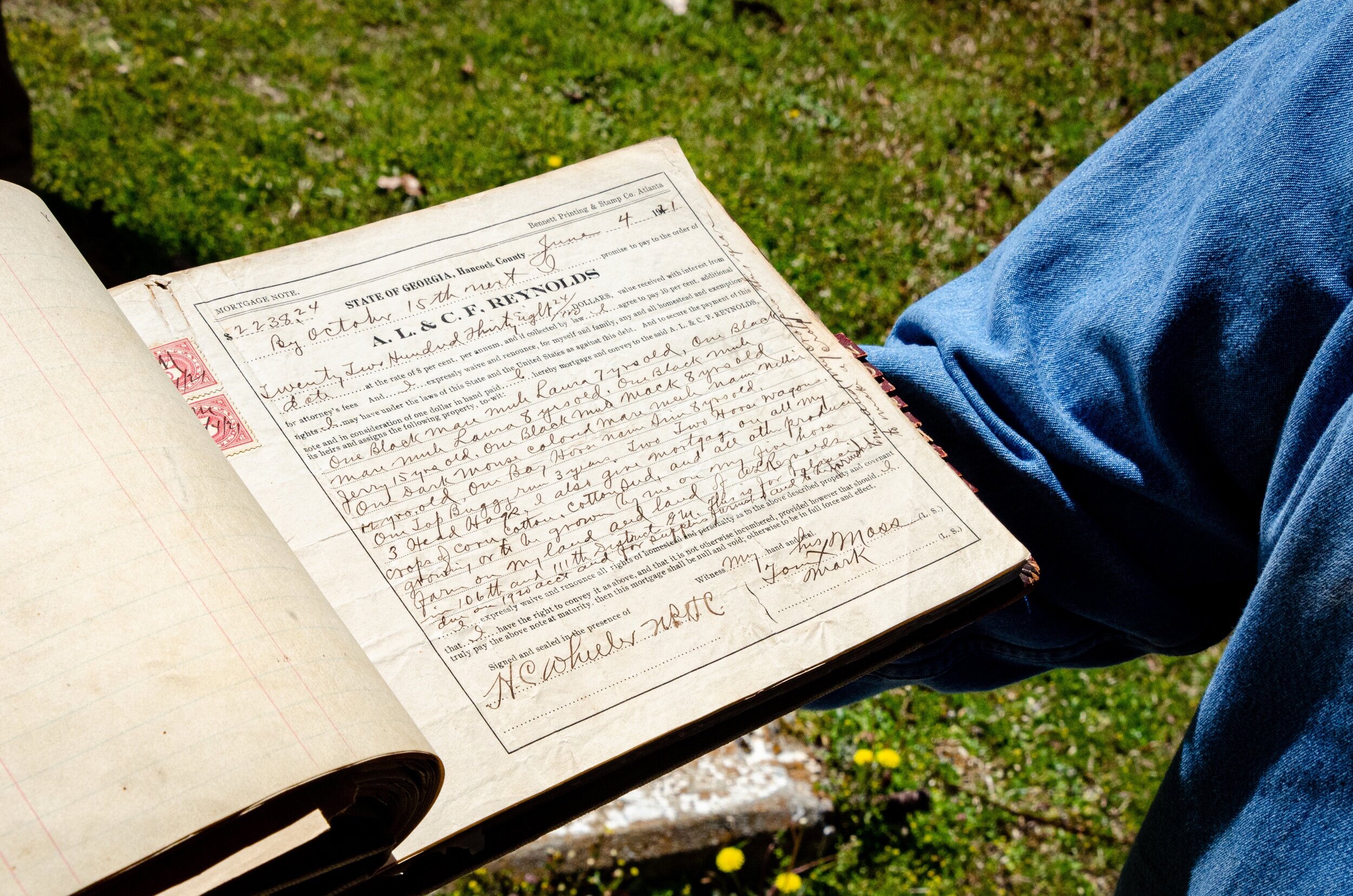

We arrive at the Ogeechee River Mill, an operational gristmill located at the Warren/Hancock county line owned and managed by Norma “Missy” Garner. She gives us a tour and shows us original ledgers, some dating back to the 1800s. Inside the mill, iron and steel pipes weave into an antique metallurgical tapestry. “See that wall across the river?” she asks, pointing at the Ogeechee’s banks. “That wall was built in the 1840s. It’s original.” She pauses before adding, “And those quarry blasts might knock that whole thing down.”

Garner fears that years of hard work restoring this historic tourist destination could fall into shambles. The blasts may destabilize the historic infrastructure while the river may be sullied from its sacred gray-blue to a constant muddy-brown. Tourists might be pushed away by the quarry’s unsightly noise and construction traffic.

After touring a few more historic sites, we talk with one of the leaders of the opposition to learn how the community is organizing against the quarry.

Norma “Missy” Garner with one of the many original ledgers in the Ogeechee River Mill. This one displays a transaction from June 4, 1921.

Carla Mayes owns the beautiful 150-acre River Bend Ranch, where she raises cattle. Like the Ogeechee River Mill, her property is located in Warren County, which abuts Hancock County on the other side of the Ogeechee. Warren County is slightly smaller, slightly whiter, and slightly more affluent than Hancock. Even though both counties share the same river, and will arguably be equally affected by the quarry, the political permitting process is entirely restricted to Hancock. Environmental regulation often follows political boundaries, like counties, instead of natural boundaries, like watersheds.

The Ogeechee River runs through over 240 miles of rural counties, stringing together the farms of middle Georgia like pearls on a necklace. As one of the least developed rivers in the country, the waterway is something to treasure, something rare. And the community knows it.

“There is no line keeping the quarry’s issues inside Hancock and out of Warren,” says Thornton.

As a light-gray eddy of water swirls beside us, Mayes explains that the river is dynamic, wild, and alive. “The thing is, something like the quarry wouldn’t bring natural change. It would bring harm. It could cave in the sides of the ravines, permanently choke it in a way from which it couldn’t recover.”

Mayes has about 80 head of black Angus beef cattle. “Everything I have here took me 15 years,” Mayes explains. “But it’s not even about the money.”

“And this takes a lot of money,” Thornton chuckles. “Trust me, I know. Farming ain’t cheap.”

“It’s the love,” Mayes continues. “The oneness with nature. When you live with the wildlife, the grass, the bees, the birds, your soul is full and happy.”

Mayes points to her wooden fence, a fair distance from the riverbank, and explains that she built her cow fencing away from the river so their manure wouldn’t pollute it.

“My cows have a happy life. They’re healthy, peaceful, fat. They run with the deer and share space with the birds. That quarry threatens to turn all that harmony upside down. It will scare away the wildlife. The cows will stop producing like they should, from noise pollution. Silica dust will get on their grass and mess with their nutrition.”

Carla Mayes at her River Bend Ranch. She printed off shirts that read “Stop the Quarry” and handed them out to protesting community members. Mayes’ cows live a happy life. She is worried the quarry would stress them with noise pollution and silica dust.

Communities that oppose quarries in other parts of the country have raised similar concerns. While there is surprisingly little science on some of these worries, they are not unwarranted. For example, noise pollution is well-known by scientists to cause chronic stress in birds and other wildlife. And a 2001 study published in the Journal of Range Management found that plants coated in silica caused sheep and cattle to have kidney stones and nutrition issues, though with some uncertainty.

Mayes and others in the community have been helping finance the Ogeechee Riverkeeper (ORK), a nonprofit group whose mission is to protect the Ogeechee River Basin. ORK, in turn, hired Stack & Associates, P.C., a public interest environmental law firm, to help legally represent the anti-quarry community in court. Through community donations, they are hiring experts in mapping, economics, geology, and environmental law to make a rock-hard legal case. Some student volunteers from the University of Georgia taking an environmental law class also helped create a legal document detailing the threats posed by the quarry. (Full disclosure: I was among those students.) Together, they make up the “anti-quarry team.”

Near Thornton’s farm, across the river, lies a preliminary construction zone. Gravel was placed right up to the very edge of the riverbank, implying construction would creep up to the very last inch possible. “That shouldn’t even be legal, to build so close to the water,” Thornton says in frustration, fearing that the lack of a buffer will cause the river to get contaminated.

“We’ll see this thing through,” Thornton tells Mayes as she wonders what will happen if they don’t win the legal hearing. “We have to stay positive. We’ll win in the end, whether in court or afterwards.”

On the day of the hearing, Damon Mullis, riverkeeper and executive director of ORK, is at Mayes’ house to help prepare for the testimonies. We converse by the river as he shares how frenzied things have been for them.

Mullis explains that the anti-quarry community members reached out to ORK because the county seemed ready to rush the quarry permitting process before the community could voice its concerns.

Thornton shares, “I do believe the county commissioners represent the people. … I believe they are smart people who will act in the best interests of the community. The problem is that they need to really be informed on what is going on here.”

County Commissioner Terrell “Ted” Reid, who presides over Thornton’s district, says he was never ready to vote yes, that he “simply did not have enough information on the applicant at the time.” Instead, he’s tried to learn as much as possible about Mayfield Natural Resources since the day he read about the quarry proposal. Mayfield Natural Resources, LLC, declined to comment for this article.

To inform the commissioners, the anti-quarry team produced a 502-page document between January and March of 2021. An abbreviated version was submitted to the county commissioners on the morning of March 24, the day of the hearing. It states that the majority of owners who actively reside within a 3-mile radius oppose the quarry.

The anti-quarry document then lists a slew of studies the quarry company should have conducted but didn’t, thus precluding a scientific understanding of the quarry’s environmental, economic, or public health impacts. This also, argued the anti-quarry team, contradicted county zoning ordinances.

A photograph of two lakes near Thornton’s catfish farm is at the heart of the document. One lake, a bit farther out from the Mayfield site, is a vibrant azure. The other, next to the cleared patch of forest across from Thornton’s catfish farm, is a muddy brown. The document explains that “ ... the impacts [of the quarry] are already occurring,” blaming the deforestation for excess soil runoff.

“If they’re not informed,” says Mullis, “it’s because they don’t want to be informed.”

The Ogeechee River and its wealth of granite rocks.

Although Mullis, Mayes, and Thornton are concerned about what this could mean for the whole community, they believe the biggest impact could be felt by the residents of the Mayfield Properties community, a cluster of more than 50 houses located less than a mile away and across a railroad track just north of the quarry site. According to the document, many participate in Section 8 affordable housing and receive government assistance.

According to Thornton, the small houses were built in the 1960s on stone slabs. However, a new manager recently bought the estates and began renovations to improve quality of life and provide affordable housing to the community. Even with these improvements, Thornton speculates that the blasts “would knock these houses right down.” The owner of Mayfield Properties Inc. declined to comment.

One resident of the community, 72-year-old Johnny Lester, was unaware of the quarry at the time we spoke. This aligns with a sentiment written in the first few pages of the anti-quarry team’s document:

“Many more [residents] likely still do not know about this looming threat for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the Applicant’s failure to make a good faith effort to involve stakeholders in this process.”

(“Applicant” being legal lingo for the quarry company, and “stakeholders” meaning the local community.)

“This is the definition of environmental injustice,” says Thornton.

Cowboy Jones, 91, is a former deputy sheriff of Hancock County. “I’ve been shot at nine times,” he says, “but I’m still here, enjoying life.”

“Whether intentional or not, the most impacted people are going to be the low-income, African American community,” Mullis adds. “At the same time, the majority of the commissioners are African American, and the people voted them in. So it’s complicated.”

Commissioner Reid views the affair as a simple case of county laws and economics. “I don’t think [race] has anything to do with this,” he says. The county chair declined to comment.

Laurie Fowler, professor emeritus at the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology and the UGA School of Law, who helped connect student volunteers with the court hearing, has a long history of working on environmental law in the South. “Even if developers don’t have any discriminatory intent, one reason they often target [impoverished] areas is because they think the community will embrace the jobs created by development.” Other reasons, she says, include lower land prices and a lack of legal and political tools to push back.

“I lived here when it was still cotton farms,” says Johnny Lester, 72. “I used to carry bags of it on my back to the mill.”

A young resident of the Mayfield community, which might have been particularly affected by quarry operations. “I just can’t imagine children having to breathe in silica dust” was a comment from local rancher Carla Mayes.

Hancock is job-hungry, with a median household income hovering around $32,000. However, the anti-quarry team is skeptical about how many jobs the quarry would create. The team’s hired economist states that virtually no information provided by the quarry company indicates a potential for impactful job growth. Quarries, the team contends, are well-known to decrease quality of life via dust, noise, and traffic.

Vulcan Materials, a nearby quarry in Sparta, says that somewhere shy of 20 of its 26 employees are local.

Mullis pointed out that a lack of resources makes impoverished areas especially vulnerable to this kind of operation. “The thing is, you need resources to fight these things,” says Mullis. “And if you as a community don’t have those resources, you can’t stop these kinds of things. People planning and developing, especially extractive things, they definitely target places that won’t give any resistance.”

There is also what Thornton calls “a talent drain.” For every 50 aspiring kids that leave a poor county to become educated or pursue a specialty, he says, maybe one will come back. Poor counties don’t have local professional diversity they can call on for help with community issues. Instead, they must rely on outsiders like contracted lawyers, which requires money for professionals who may not understand the community.

This is not to say that all quarries are unwelcome. Rhoda Allen, who has lived in Hancock County for 28 years, has good things to share about Vulcan Materials in Sparta with regard to its attention to environmental impact. For example, she says, Vulcan actively tries to prevent pollution into a nearby creek. “They are responsible and enforce safety. They actively make you aware of respiratory danger via repeated exposure. They did not build in a residential area. Never did anything to make my antennae twitch.” She also calls them community-oriented, saying that when the local library was financially struggling due to COVID-19, Vulcan stepped up and contributed.

A lack of transparency on what the new quarry would look like or what the company plans to do is “one of the frustrating things about this whole situation,” says Thornton.

“You always hear Georgia is the best place to do business,” says Mullis. “There’s a reason for that, and a lot of it is our lax rules and regulations.”

Fowler emphasizes the lack of protections for the vulnerable in these sorts of predicaments. “We have miles to go before amending our laws to provide for environmental justice and sustainability in general,” she says. For example, HB 432 was introduced in February 2021 to create an Environmental Justice Commission in the state of Georgia. However, it was not even addressed in the 2021 Georgia legislative session, which adjourned in April. And instead, Fowler says, “[Georgia] enacted a law making it more difficult for communities of color and others to vote!”

On March 24, 2021, a few days after our visit to Mayes’ ranch, a hearing is held in the Hancock County seat of Sparta on whether or not to permit the quarry. Due to COVID-19, the courthouse is allowing only 10 citizens into the room, limiting access and representation. Everyone else will have to watch through Zoom as Thornton, Mayes, Mullis, and a few others give their testimonies before the commissioners vote.

As the clock strikes 4, protesters gather at the courthouse steps with their self-funded signs and shirts. Given the tiny population of the town and county, the turnout of some three dozen people feels massive.

The camaraderie is infectious. Cars honk in jubilant support as people wave in return. People chatter as if they are longtime friends. Two protesters get excited when they realize they lived in the same trailer park near Georgia Southern in the 1970s.

Amid the crowd of red shirts and white signs, a shining silver belt buckle stands out. Cowboy Jones, 91 years old, is here with gusto. He formerly served as a deputy sheriff of Hancock County and was a leader of Hancock in the 1970s. “John McCown was my right-hand man,” he proudly shares. “He was a great man.”

As the American flag billows above the Confederate monument across from the courthouse, he comments on the racial tumult of the 1970s McCown era. “White folks still don’t like me,” he says, explaining that even today some people want to harass and argue with him. “That’s why I always carry a .38 on my hip,” he says.

Aside from the rumbling of trucks and friendly conversation, the protest feels like a silent culmination. There are no chants, and words are shared quietly. However, once Thornton, Mullis, and Mayes head inside, people settle onto the courthouse steps and a soft anxiety creeps through the crowd. They pull out phones and computers to watch the hearing. No one is sure what to expect.

Testimonies are hard to hear through the digital crackling. The courthouse is streaming the hearing via a smartphone, and the audio suffers for it. Eventually, Johnny Thornton’s voice inside the courtroom rings loud enough to be heard clearly. While previous testimonies included statistics, legal issues, ecological impact assessments, and other formal arguments against the quarry, Thornton begins differently. “Last night, I was meditating on the Scriptures,” he says. “I am not the owner of the catfish farm. Well, technically I am. But I’m not taking it with me when I’m gone. God is its owner, and I am its steward.” His speech blossoms into the definition of stewardship, the duty of humankind, and our moral obligation to protect nature.

Two women watch the courthouse hearing virtually while sitting on the steps of the ornate Victorian structure.

As clouds coalesce in the evening heat, the hearing finally finishes. Because of the poor audio, no one can tell how the votes came out. Confused and a little agitated, people begin hesitantly rising and wait for the courthouse doors to open.

One by one, Mullis and the rest emerge, hands in the air. After the testimonies, the commissioners voted unanimously, 4-0, to deny the quarry permit. Jumping, laughing, hootin’ and hollerin’ rock the courthouse steps. The hand of a red-shirted protester heartily shakes the hand of a gray-suited lawyer. Affection spreads freely.

A mere two months before, the commissioners would have been able to permit the quarry with little pause. But the community seized the issue with their own hands and flipped it on its back.

In a moment of tenderness, Cowboy Jones gathers everyone into a circle and delivers a prayer offering thanks to God for protecting their land and delivering them through this peril.

In just the way a fog disperses in the morning light, the crowd dissipates, their dream realized. From modest housing and historic sites to pristine wildlife and catfish farming, a way of life in Hancock County is momentarily preserved from further damage.

Since the March 2021 hearing, the Ogeechee Riverkeeper has begun working with county commissioners to implement an ordinance that would prohibit reapplications of quarry permits.

“Counties like this need a vision of what they want to look like,” says Rhoda Allen. “They need comprehensive planning. Right now in Hancock, your neighbor could suddenly be a pig farm or a quarry. The zoning laws need to change.”

An elated Damon Mullis emerges from the courthouse, testimony materials in hand.

Krishna Sharma earned his M.S. at the University of Georgia studying butterfly migration. He was subsequently an AAAS Mass Media Fellow and wrote environmental science stories for the Miami Herald. He is now assistant social media manager for Kaiser Health News. You can see more of his work at www.krishnasharma.info.