Journalist Rob Perez’s investigative reporting on the decadeslong failure of Hawaii to return Native Hawaiians to ancestral lands helped bring policy changes and $600 million in landmark legislation for Hawaiian Home Lands and national recognition, winning an Excellence in Investigative Reporting award from the Asian American Journalist Association.

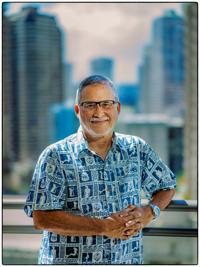

Journalist Rob Perez’s investigative reporting on the Native Hawaiian homesteading program won two Journalism Excellence Awards from the Asian American Journalists Association last month. “I am very interested and attracted to writing about and doing investigations on programs that affect indigenous or marginalized people. Especially if I can somehow tell stories that have meaning and impact ... to ... the Guam arena,” Perez said. He is part of Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary “Manaotao Sanlagu: CHamorus from the Marianas,” translated as “our people, the CHamorus, overseas,” featured weekly in the Pacific Daily News and at sanlagu.com.

It is one of the high points of the Honolulu Star-Advertiser investigative reporter and ProPublica Distinguished Fellow’s 43-year career working for newspapers in Hawaii, California, Florida and his native Guam.

“When I look back on my 40-plus years, that’s got to be at or near the top in terms of the highlights,” Perez said — not of this recent accolade, but of yet another memorable journalistic experience that happened 41 years ago on Guam.

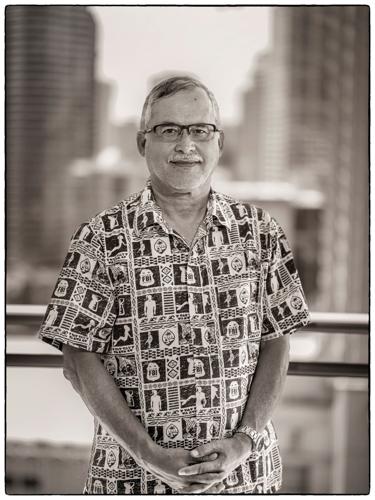

Honolulu Star-Advertiser investigative reporter Rob Perez doing an interview on Big island in 2021.

Career highlight

“I was hoping that you’re going to ask about one of the highlights of my journalism career because it was on Guam,” Perez said as he started off our interview.

“When Pope John Paul II arrived on Guam on February 23, 1981, I was assigned to write the lead story. And then the next day when he left, I was assigned as photographer at the airport, for his departure.

“There were hundreds, if not thousands of people there along a rope line at the old airport. And that’s where I was stationed just in case he walked over, and so sure enough he deviated from his scripted schedule, walked over to greet the crowd along the rope line,” Perez said with the confidence of memory about a story he has recounted numerous times.

“I jostled and made my way up to the front of the rope line with my wide-angle lens on my Nikkormat and started shooting away as he was walking down the rope line in my direction. I was shooting and shooting and shooting and then next thing I know there’s a hand extended to me that I could see on the viewfinder of my camera. So I dropped my camera and shook his hand and then he continued on down the rope line,” Perez said.

At this point, most journalists would stop and savor the moment, but not Perez.

“So I ran down, I don’t know how many more yards, made my way to the front again and was shooting and shooting and shooting more photos. And the next thing you know, he sticks his hand in my camera again. So I shook it again,” he added.

“It’s hard to top that story, because I was raised Catholic, my parents were devout Catholics and most of the island was Catholic,” Perez recalled. “And wow, you’re at the beginning of your career, and you get to cover the pope on your home island, and not only do you get to cover him, you get to shake his hand twice and in the span of a few minutes.”

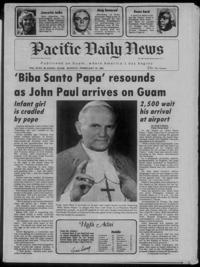

Ever the consummate professional journalist, Perez wanted to confirm dates and recollections and he went on newspaper.com and downloaded a digital copy of the Pacific Daily News coverage of the 1981 papal visit to Guam.

There on the PDN front page was his reporter byline and on an inside photo spread was his photo, captioned, “the pope presses the flesh at the airport just before leaving.”

Photos of Pacific Daily News archived pages show coverage of Pope John Paul II’s visit to Guam in 1981.

These photos of Pacific Daily News archived pages show coverage of Pope John Paul II’s visit to Guam in 1981.

Perez and I both started our journalism careers at PDN as summer interns. When he graduated from University of California, San Diego, and started full-time in 1979, I was headed the opposite direction, transferring from University of Guam to University of Missouri.

As a fellow journalist and a CHamoru growing up Catholic on Guam, his encounter with the pope resonates with me, albeit with a tinge of envy and jealousy.

He laughed when I told him I was jealous of him. I explained that I was part of the Detroit Free Press editorial team that covered the 1987 papal nine-city U.S. tour that concluded in Detroit.

I told him, “I photographed the pope in Miami, San Antonio, Phoenix, Los Angeles and San Francisco, but I never got that close, let alone ‘press his flesh.’”

I asked Perez if the pope said anything to him and he replied, “I was so dumbstruck and in awe, that if he said anything, I didn’t hear it. I was just like, wow, I just shook the pope’s hand and then when I shook it again, I said I must be blessed for life.”

Guam roots

Perez grew up on the Hyundai housing subdivision of Sånta Rita-Sumai and is the second oldest of five children of Beatrice Blas Calvo, familian Calvo/Dero, and Ricardo V. Perez, familian Cotla and Gollo.

Rob Perez, center, with his four siblings in this 2021 photo. From left: Rick Perez, Lisa Bautista, Nora Garces and Tim Perez.

He grew up in a time when seemingly throughout the island CHamoru parents felt that fluency in English was the key to career success.

“My parents made the decision early on not to speak CHamoru to us at home, because they wanted us to succeed, get good jobs and good education. And my mother was a CHamoru instructor,” he recalled. “I think they did that because they wanted us to assimilate and get an education that would increase our chances of doing well.

In this early 1970’s photo Rob Perez, standing at far left, with his four siblings and his parents, Beatrice Calvo Perez and Ricardo Victor Perez, at their Hyundai housing subdivision of Sånta Rita-Sumai.

“So we’ve all done well, but at times, I think it was partly at the expense of, at a minimum, not learning my native language,” he added. “That’s a big regret I have and when I retire in a couple of years, high on my to-do list is learning the CHamoru language.”

Regret notwithstanding, he quickly added. “I don’t speak CHamoru, yet I consider myself as CHamoru as anyone around because, it’s more about your values and your beliefs. I know who I am, I know my identity, and it revolves around being CHamoru.”

And it revolves around being a journalist at a high level for decades.

“I always knew I wanted to be a journalist. I don’t have formal journalism training. I didn’t even work for my high school or college newspaper, but I have always liked to write and I’ve always liked to ask questions,” he said.

He met his future wife, Betty Shimabukuro, when they were both working at PDN from 1979 to 1983. Since then, they have worked in the same newsrooms in Florida, California and Hawaii for four decades — except for five years in 2005-2010, when she was working at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and he worked at The Honolulu Advertiser.

Rob and Betty Perez at right with their three children, from left, Justin, Caleb and Christine. Photo taken in 2014 at a Calvo family reunion in Las Vegas.

The papers merged in 2010 and became the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, and the couple became co-workers again until she retired last year.

“One of the advantages I have is being married to a journalist, who happens to be a much better editor than me,” he said. “I can let her read my copy before I turn it in, and ask her what she thinks and sometimes she can be very, very, very brutally honest. And tells me ‘I don’t understand this at all,’ or whatever, and then that always helps improve the story.”

They left the PDN in 1983 and transferred to a newspaper in Florida, worked there for a few years, went to California, worked there for a few years, and then ended up in Hawaii. And with the exception of a two-year stint in Orange County, California, they have been in Hawaii since 1988.

“We decided that this (Hawaii) would be nice if I couldn’t be on Guam. I’m an island boy at heart. I love living in the islands,” he said. “We were lured away from Hawaii in the early ‘90s to work at the Orange County Register. But after two years, I knew I needed to get back to the islands.”

He felt that Hawaii was the best place to raise their three children. “They’re half CHamoru, a quarter Japanese, a quarter Chinese, so I like to think the CHamoru is their overriding identity,” he said.

“From the time they were kids till even now, I really emphasize their CHamoru heritage and try to remind them of the values that are important to us as CHamorus. The values of family and respecting the manamko’, that’s what I try to instill in my kids over the years.”

Throughout his newspaper career, Rob Perez has been a reporter, investigative reporter, columnist copy editor, business editor and assistant city editor.

“There’s no question I like writing and reporting, which is why I deviated from going into management,” he said. “I wanted to be just the reporter. I think that’s my strength and where I can make a difference.”

Journalist Rob Perez’s investigative reporting on the Native Hawaiian homesteading program won two Journalism Excellence Awards from the Asian American Journalists Association last month. “I am very interested and attracted to writing about and doing investigations on programs that affect indigenous or marginalized people. Especially if I can somehow tell stories that have meaning and impact ... to ... the Guam arena,” Perez said. He is part of Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary “Manaotao Sanlagu: CHamorus from the Marianas,” translated as “our people, the CHamorus, overseas,” featured weekly in the Pacific Daily News and at sanlagu.com.

ProPublica

These past few years he has made a difference, especially as one of six inaugural members of the ProPublica Distinguished Fellows program.

The program funds reporters’ salaries and benefits for three years as they produce important investigative projects from their home newsrooms on topics affecting their communities.

“It’s important to ProPublica and to me as a CHamoru journalist to be the voice of marginalized people, people who are underrepresented and who often aren’t reflected fully and adequately in the mainstream media,” he said.

“My investigative efforts to date with ProPublica had been mostly about the native Hawaiian people and how a program here to get Native Hawaiians onto their land through homesteads has really been very dysfunctional for decades.

“I get to work at a job where I can truly make a difference in people’s lives. Whether it’s through triggering changes in the law, or changes in policy or, contributing to legislation to appropriate $600 million for a homesteading program, the fact that I’ve been able to have a hand in that — I mean, to me, I can’t imagine a better job in the world than what I’m doing now,” he added.

He has a few more years on his fellowship and is continually writing more about the Hawaii homestead investigation but he has future ambitions that include Guam.

“I’m going to propose some stories that have a Guam angle, so that I can merge my two interests of writing about Hawaii issues, and then finding topics that have some kind of parallel or some kind of connection to Guam, because I wanted to write more about my, my home island,” he said.

Judging by the results, Pope John Paul II indeed blessed this journalist that fateful day in 1981.

“I do feel blessed when the stories result in real impact that will benefit people for years, it’s all the more gratifying and it’s all the more reassuring that my decision 40-plus years ago to be a journalist — in my heart it was the right decision,” he said.

“When I look back on my career, and how I started — a graduate of a Guam public school, and growing up on an island — I’m proud of what I’ve been able to achieve, coming from the background that I came from. And I’m proud that I’ve been able to make a small difference in the world through my writing. That a CHamoru from a small island has been able to make a difference,” he said.

“And I’m sure a lot of people that you’ve talked to through this project, they feel the same way — that CHamorus, in their small ways, move away and are making a mark on the world. To me, it’s very gratifying and hopefully it helps inspire and motivate other CHamorus to do the same thing.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.