The Anti-Semitism We Didn’t See

DeSean Jackson’s Hitler moment—and mine—showed that Black Americans’ experience of racism doesn’t automatically sensitize us toward other forms of prejudice.

Like DeSean Jackson, the Philadelphia Eagles wide receiver who is being condemned for posting a fake Adolf Hitler quote on his Instagram feed last week, I too have had an ill-advised Hitler moment.

In 2008, I was a general columnist for ESPN.com, covering the NBA Finals series between the Los Angeles Lakers and the Boston Celtics. Heading into Game 5, I wrote a piece about how it saddened me, as a lifelong Detroit Pistons fan, to see that the Celtics were no longer as widely hated as they had once been. Trying to be funny and whimsical, I drew upon my memories of the Pistons having to beat the Celtics before winning their first NBA championship in 1989. I ended up writing, “Rooting for the Celtics is like saying Hitler was a victim.”

More than a decade later, I still cringe when I think about it. Not only had I severely insulted the Celtics’ fan base, but I had made a joke about the Nazi leader who orchestrated the murder of 6 million Jewish people. I was, of course, aware of the Holocaust, but I had given little thought to the feelings of the Jewish community because, frankly, it wasn’t my own. When others pointed out the insensitivity of my statement, I was mortified. I apologized and wrote an entire column asking for forgiveness. ESPN suspended me for a week, a punishment that I deserved.

Like Jackson, I am Black. And had anyone made a remark trivializing slavery, I would have been incensed. I learned that just because I’m aware of the destruction caused by racism, that doesn’t mean I’m automatically sensitive to other forms of racism, or in this case, anti-Semitism. Black people, too, are capable of being culturally arrogant.

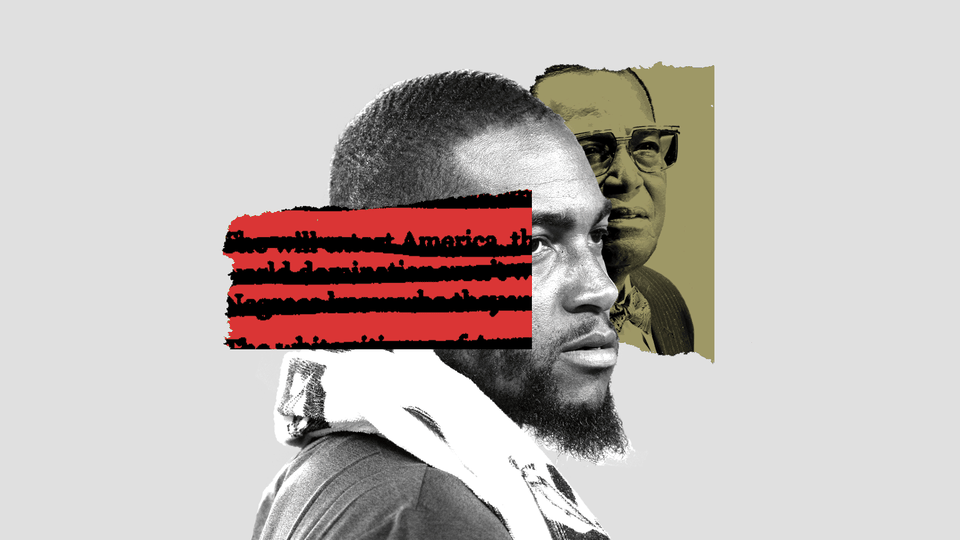

Which brings me back to Jackson. On Instagram, the 33-year-old went much further into ugly territory than my flippant comment about Hitler. He posted a screenshot of a passage, falsely attributed to Hitler, declaring that white Jews “will blackmail America. [They] will extort America, their plan for world domination won’t work if the Negroes know who they were.” The passage—which has been attributed to various writers—went on to say that “Negroes are the real Children of Israel.”

Perhaps Jackson thought some part of this would be inspirational for the Black community. But the passage was anti-Semitic regardless of its author. And why would Jackson think that it was remotely constructive to insert Hitler, of all people, into a conversation about racial empowerment? After all, Hitler hated Black people too.

In other posts around the same time, Jackson shared quotes from a speech made by the Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan during the Fourth of July weekend. The speech mostly centered on police brutality, the coronavirus, Black empowerment, and self-reliance. But with Farrakhan’s long, vile record of anti-Semitism, Jackson—who is far from alone among Black Americans in his support for Farrakhan—can’t be surprised that people now question his true feelings toward Jews.

Jackson subsequently apologized publicly and privately to the Philadelphia Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie, general manager Howie Roseman, and head coach Doug Pederson, but that might not be enough to spare him from being suspended or even cut.

Regardless of what happens with Jackson, the unfortunate truth is that some Black Americans have shown a certain cultural blindspot about Jews. Stereotypical and hurtful tropes about Jews are widely accepted in the African American community. As a kid, I heard elders in my family say in passing that Jewish people were consumed with making money, and that they “owned everything.” My relatives never dwelled on the subject, and nothing about their tone indicated that they thought anything they were saying was anti-Semitic—not that a lack of awareness would be any excuse. This also doesn’t mean that my family—or other African Americans—are more or less anti-Semitic than others in America, but experiencing the pain of discrimination and stereotyping didn’t prevent them from spreading harmful stereotypes about another group.

Jackson is far from the only prominent Black athlete or entertainer to have amplified anti-Semitic tropes in recent years. In 2017, the Anti-Defamation League, which monitors acts of hatred, expressed concerns over a song in which the hip-hop artist Jay-Z rapped, “Jewish people own all the property in America.” In 2018, the Atlanta rapper 21 Savage’s song “ASMR” created a firestorm because he rapped, “We been getting that Jewish money. Everything is kosher.” The basketball star LeBron James shared that lyric in an Instagram post, which added to the controversy. Later, James offered only a tepid mea culpa. “I actually thought it was a compliment,” he said.

In the past few days, Jackson’s offensive social-media postings haven’t received the universal disapproval that they merit. His teammate Malik Jackson and the former NBA player Stephen Jackson defended him. At a time when there is an understandable focus on how Black Americans bear the brunt of systemic oppression and police brutality, some commentators believe that people are afraid to rebuke Jackson, because it may hurt the movement.

Black people’s fight for their humanity is unrelated to Jackson’s error, but they must use their own racial experiences to foster empathy for others. Even in his apology, Jackson showed little recognition of what he’d done. “I post a lot of things that are sent to me,” the Eagles receiver said in a statement. “I do not have hatred towards anyone. I really didn’t realize what this passage was saying. Hitler has caused terrible pain to Jewish people like the pain African-Americans have suffered. We should be together fighting anti-Semitism and racism. This was a mistake to post this and I truly apologize for posting it and sorry for any hurt I have caused.”

The thirst for liberation and equality can never come at the expense of dehumanizing other marginalized groups—especially at a time when hate crimes against Jews have increased significantly. A record number of anti-Semitic incidents was reported last year.

Jackson has reportedly reached out to a Philadelphia rabbi in an effort to become more informed. The New England Patriots wide receiver Julian Edelman, who is Jewish, has offered to accompany Jackson on visits to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Jackson has already met with a 94-year-old Holocaust survivor, but he should also take Edelman up on his invitation, too.

When I apologized to Jewish friends about my Hitler reference, they offered their support—but also an overdue education in how dangerous casual anti-Semitism can be. Those phone calls forced me to recognize how I had centered my own experience above others who came from painful histories.

The good news for Jackson is that some are willing to characterize this incident as ignorance rather than hatred. Regardless, Jackson is going to have to work to regain the trust of the Jewish community—and everyone else who understands that Hitler was evil. Just because he says he’s sorry doesn’t mean they have to believe him.