Mexico’s president looks to upend energy reform measures

Critics say legislation may disrupt use of renewables, hamper investments by foreign companies

Andres Manuel López Obrador never liked Mexico’s energy reform measures when they passed in 2013 and 2014 and now, in the third year of his six-year term as the country’s president, he appears poised to try to severely weaken them — and boost the fortunes of the state-run electric company at the same time.

At issue is a controversial bill that has passed through the country’s Legislature the populist president says will help Mexico become more energy independent. But critics say it will discourage investment in the country’s energy sector and slow the development of renewable energy, among other sources of electricity.

Opponents say the legislation is unconstitutional — something López Obrador disputes.

“There is nothing in it that violates constitutional rights — nothing, nothing, nothing,” the president said last week during one of his morning news conferences.

The bill would change the order in which electricity is dispatched into Mexico’s grid, giving priority to the Federal Electricity Commission, the state’s electric company, known as CFE for short.

Under the energy reform measures, priority was based on the generation delivering the lowest cost. That formula helped renewables such as wind and solar — which have received a lot of private investment — because of their low prices.

If enacted, the new legislation would put hydropower from CFE at the front of the line.

“This will put renewables at the bottom of the totem pole,” said John Padilla, a managing director at IPD Latin America, an energy consulting firm. “It certainly hurts them.”

The change has also rattled some investors and angered political rivals.

Investors came into Mexico “trusting in the rules in the law,” Xóchitl Gálvez Ruiz, a senator from the opposing National Action Party, told the New York Times. “Overnight, they are told, ‘You know what? I don’t like that, I’m going to change the rules.’”

But the president, known colloquially by his initials, AMLO, has long maintained energy reform unfairly diminished the roles of CFE and PEMEX, Mexico’s state oil company, and bringing them to prominence will make the country more energy independent.

Last month, AMLO pointed to the deep freeze in Texas that not only caused power outages in the Lone Star State but resulted in cutoffs in natural gas deliveries to Mexico that led to blackouts in most of the country.

“We cannot rely on one single fuel for power generation,” López Obrador said.

One of the biggest private energy companies in Mexico is IEnova, a subsidiary of San Diego-based Fortune 500 company Sempra Energy.

Among its assets, IEnova operates one of the biggest wind farms in Latin America, called Ventika, with 84 individual turbines in the state of Nueva Léon. The company also jointly owns a wind farm on a mountain range in Baja called Energía Sierra Juárez.

IEnova’s solar investments include four utility-scale solar plants, including Don Diego Solar in the state of Sonora that opened late last year. A fifth solar plant, called Border Solar outside the town of Juárez, is getting commissioned.

IEnova has been careful in its comments about the legislation. “IEnova continues to evaluate the measure,” a Sempra spokeswoman said in an email Monday to the Union-Tribune.

“We have tried not to be in the middle of that fight,” Sempra CEO Jeff Martin told analysts at the company’s earnings call two weeks ago. “Our goal is to help Mexico be successful. They need more foreign direct investment.”

Last November, IEnova received a long-sought final permit from the López Obrador government to add an export component to a liquefied natural gas, or LNG, terminal at the Energía Costa Azul facility outside Ensenada. When completed, the facility figures to be very profitable because it will be able to ship LNG to gas-hungry markets in Asia without having to pay tolls at the Panama Canal.

The understated reaction to the bill does not surprise Jeremy Martin, vice president of Energy and Sustainability at the Institute of the Americas, a UC San Diego think-tank specializing in North American public policy.

“At the end of the day, Sempra and IEnova have made a long-term bet on North America,” Martin said. “Energy is a long-term business; it’s a long-term commitment to the market ... There will be some companies that will keep their heads down and hope that in three years things will swing back a little bit.”

Reform has generated an estimated $200 billion in foreign investment in Mexico’s energy sector but many Mexicans, Martin said, do not see how those investments have improved their every-day lives.

“For (López Obrador), this is about Mexico’s sovereignty,” Martin said. “He’s a 1960s and 70s guy who says Pemex should be doing everything and what they’re not doing, CFE should be doing ... It’s energy nationalism, it’s resource nationalism.”

A similar measure had been put forth by Mexico’s Energy Ministry but last month the country’s Supreme Court struck it down, saying it violated the right to free competition. But just days before the decision, López Obrador and his supporters came back with their counter-reform bill to the Legislature.

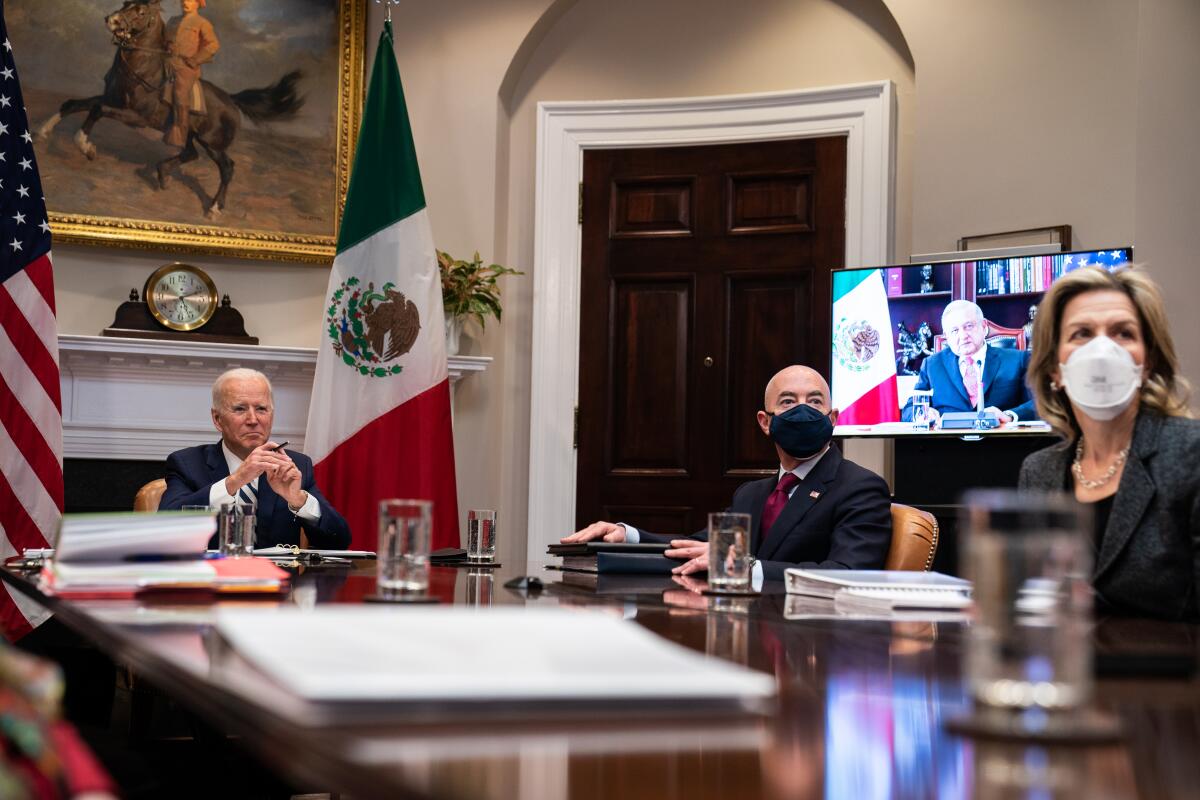

Critics also say the legislation violates the newly signed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement. President Joe Biden had a virtual meeting with López Obrador last week but the bill was not discussed.

Lawsuits are expected to be filed once López Obrador signs the legislation into law.

But Padilla, who called the legislation illegal, said even if the bill is eventually reversed, it would be to AMLO’s benefit because striking it down would take time.

“You can expect arbitration cases would not be decided upon until probably the end of this (López Obrador) administration and into the next,” Padilla said.

Midterm elections are coming up in June. AMLO’s Morena party holds the congressional majority and is looking to gain a supermajority, which would allow for making changes to the country’s constitution.

Get U-T Business in your inbox on Mondays

Get ready for your week with the week’s top business stories from San Diego and California, in your inbox Monday mornings.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.