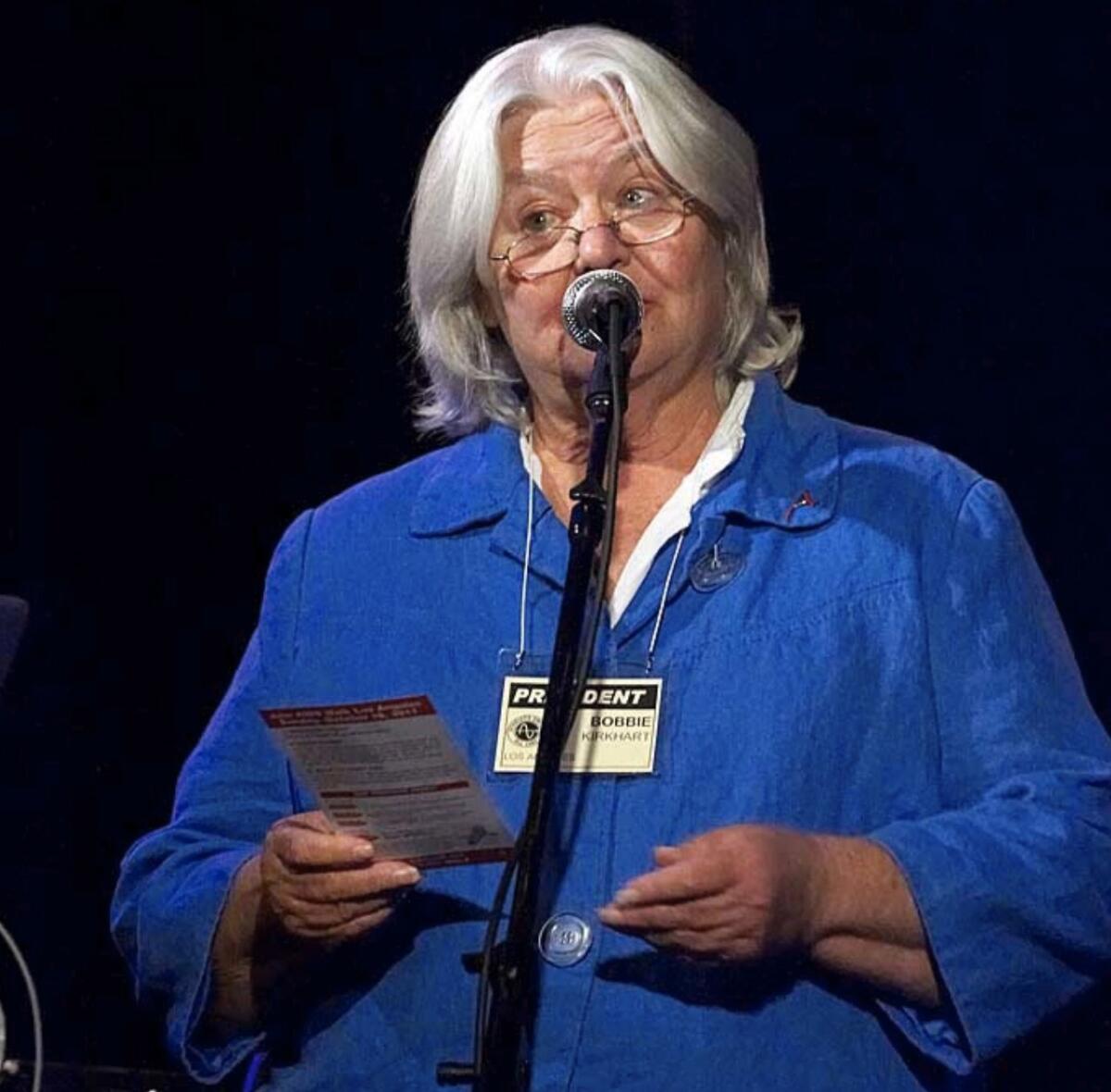

Bobbie Kirkhart, the matriarch of atheism in L.A., dies at 78

Some people find God in nature. Bobbie Kirkhart found atheism.

The free-thought activist’s anti-epiphany occurred on a lonely beach in Mazatlan, Mexico, in 1973 when she was pregnant with her first child.

She wanted to know exactly where she stood on God before she became a mom, and vowed she wouldn’t stray from the sand until her beliefs were clear.

It took six hours, but eventually she concluded that the God she’d grown up believing in would not allow so much suffering to flourish in the world, and therefore couldn’t exist.

“I came off the beach an atheist,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 2009.

Over the next 40 years, Kirkhart would become the matriarch of L.A.’s atheist community, serving as president of the Atheist Alliance International — a nonprofit advocacy organization committed to educating the public about atheism, and Atheists United, which promotes the separation of government and religion and is dedicated to creating an atheist community in Southern California.

She lectured internationally on free thought, supported student atheist groups and an atheist summer camp for children, and mentored dozens of leaders in the movement before her death Sunday at 78 at her home in Echo Park.

“She was one of the few national female leaders for the past 40 years and a trailblazer, not just as an institutional leader, but also for building connections,” said Evan Clark, executive director of Atheists United. “She was an international figure for free thought.”

Among Kirkhart’s proudest achievements was providing atheists the sense of community and belonging that is more often found in religious settings.

“She wanted people without faith to have the community she remembers growing up with as a Methodist,” said her daughter, Monica Waggoner. “Her legacy is the community.”

Kirkhart regularly opened her six-bedroom Victorian home, known as Heretic House, free of charge for fundraisers, board retreats, holiday parties, recovery meetings and choir practices. It also served as a de facto bed and breakfast for anyone from the movement in need of a place to stay.

Even during the worst of the pandemic, Heretic House hosted as many as 10 events a month, Clark said.

“Atheism was something she was serious about, but what she felt was really missing was the heart,” said Waggoner, who also identifies as an atheist. “Just because we don’t believe in a soul doesn’t mean we don’t have an emotional life that needs to be nourished.”

Kirkhart was born April 16, 1943, in Enid, Okla., and raised in a religious family. She grew up loving church — the community, the music — and even worked as a Sunday school teacher.

Her belief in God began to falter after she graduated college and started a career as a social worker for the Department of Children and Family Services in South Los Angeles in 1965. She was dismayed to learn that some of the families she served were giving money to their church, even as they struggled to feed their children.

“My clients were Black and Latino women who were God’s most fervent servants, and my God was at best leaving them to very cruel elements,” she said in a 2009 interview.

She considered other religions, but found they didn’t make sense to her either.

Atheist organizations were harder to find before the dawn of the internet, and it wasn’t until after she divorced her first husband, L.A. historian William Mason, in 1982 that Kirkhart started attending Sunday morning meetings of the newly formed Atheists United.

In those early days she kept her atheist activities away from her daughter.

“I was with my dad Sunday mornings, and she didn’t want to burden me with that,” Waggoner said.

Eventually, Waggoner caught on. After overhearing her mom use the word atheist, she asked if that’s what they were.

“She said, ‘Oh, honey, I’m so tired of being nothing. I’m glad we’re something,’” Waggoner said.

Kirkhart met her second husband, Harvey Tippit, through Atheists United and the two married in 1997. After her second marriage, Kirkhart had more financial resources than she’d ever had before. She’d grown up poor and struggled financially as a single mom.

“Top of mind was that now she could help people in a different way,” Waggoner said.

Kirkhart and Tippit traveled the world, including trips to Borneo and the Galapagos. Kirkhart also spoke to atheist and humanist groups in Canada, Germany, France, Nigeria, India and Cameroon. She was a platform speaker at the first Godless Americans March in Washington, D.C., in 2002, and sat on the advisory board of the Humanist Assn. of Nepal and on the board of Camp Quest, an atheist summer camp.

Tippit died in 2006, and Kirkhart bought Heretic House three years later in Angelino Heights. Immediately she offered it up as a community space, hosting musical performances, book clubs and Atheists United meetings and allowing people in the movement to stay with her for weeks and months at a time if necessary.

“She grew up with a lot of religious influence around her, and she’s always been someone who sees the success of the religious model as something the atheist doesn’t do enough,” said Yari Schutzer, a leader of the Voices of Reason choir, which rehearsed at Heretic House. “She got that house with the full intention of creating a community. It gave her a physical platform to say, ‘This is what I mean.’”

As her health declined in the last decade, Kirkhart stepped back from her work on the international atheist scene and instead focused on the local community through her work with Atheists United.

The organization she joined in 1982 now has 200 dues-paying members and hosts drug and alcohol recovery groups, a hiking club and the Voices of Reason choir, and is involved in community service such as food distribution and vaccine drives.

“We’re hosting almost 30 events a month,” Clark said.

Although she was an outspoken atheist, Waggoner doesn’t remember her mother having any particular enemies.

“She was nonconfrontational,” Waggoner said.

From Kirkhart’s perspective, what an individual believes is not important. Her issue was with the influence religious institutions wield and her belief that has hurt people.

In a speech to the Secular Student Alliance in 2013, Kirkhart said that an atheist’s devotion to free thought should be equal to or greater than a religious person’s devotion to God.

She believed that as long as the majority of the nation believes in “magic,” there will be an assault on science that shortens lives and creates environmental disaster.

The work of atheists, she believed, was no less than to save humanity.

“Our job is to provide an alternative to show that a life of unbelief can be, and usually is, fulfilling and productive,” she told the students. “Our job is no less than to save the world from superstitious self-destruction.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.