West Asian Cultures Beyond the Anthropological Lens

August is Photography month here at QAIC. In honor of this month’s theme, QAIC fellow Abdelrahman Kamel explored the history of photography in the Middle East, from its use as a tool for anthropological documentation to a medium for activism and protest. Abdelrahman studies at Queen’s University in Canada, where he is pursuing a Ph.D. in Cultural Studies.

Looking at the West Asian region through social media posts, vacation photographs and postcards makes some of us wonder about the history of photography in the region. Such a history has gone through different phases of development and had a profound role in representing the diversity of cultures and traditions of the Middle East to the rest of the world. The first photographic collections were documented during anthropological expeditions to the region. The problematic aspect of such reality is that photos of the Middle East were taken for the purpose of a holistic documentation and analysis of the region rather than a representation of individuals and their unique relationship with their culture. However, during the mid and late 20th century photography took on a more personal and symbolic character. Keep reading to learn more about the development of West Asian photography from a tool of visual holism to a sociocultural phenomenon of representation and empowerment.

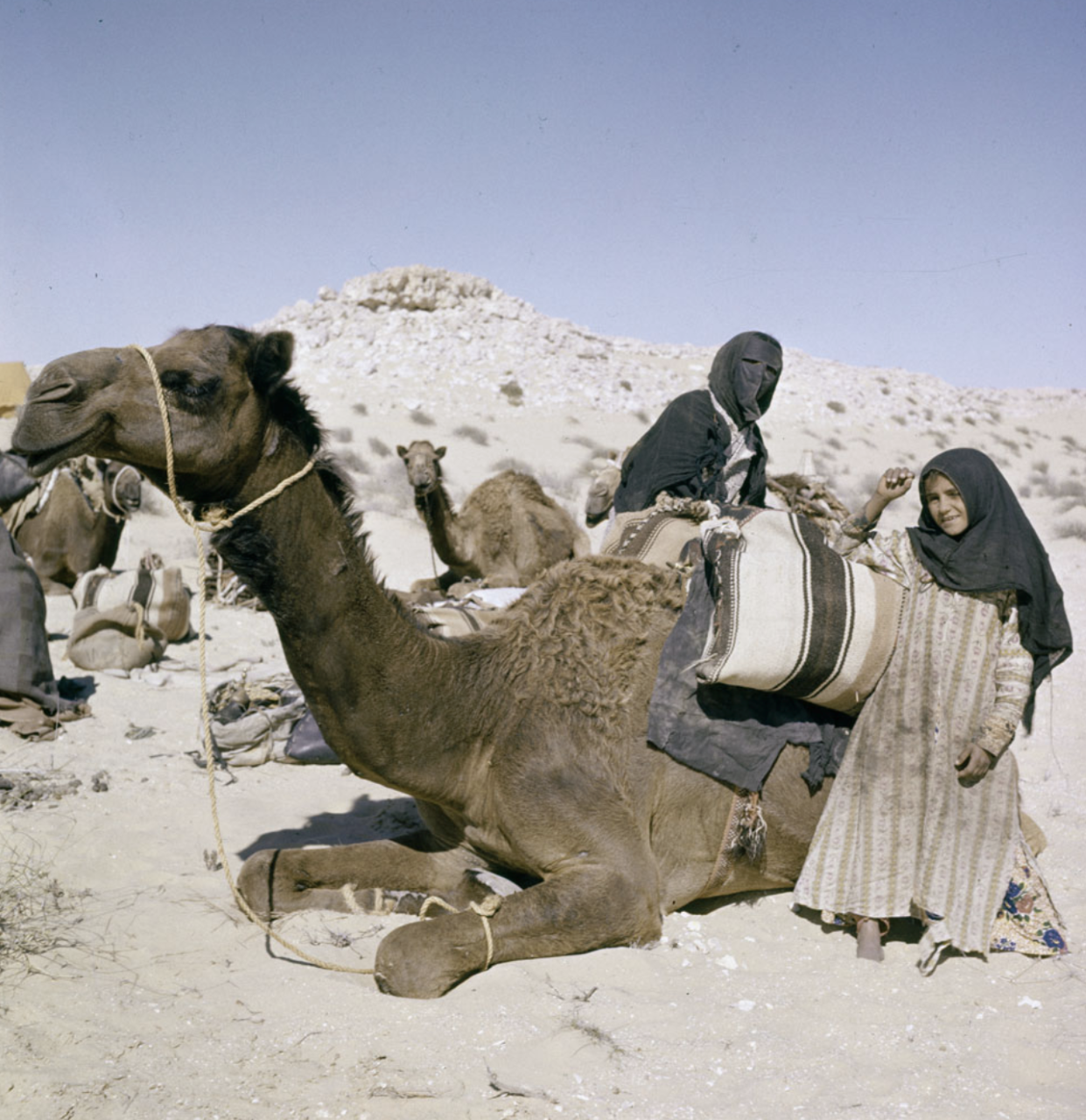

Anthropological photography during expeditions to the Middle East in the 20th century was mainly concerned with the documentation of visual elements as primary sources of reference. One of the earliest documented visual collections on the life and culture of Qataris was captured by Hermann Burchardt in his exploration in 1903 and the 1959 Danish anthropological expedition to Qatar. These two explorations produced a short documentary titled “Bedouins” alongside a wealth of photographic collections on the life of Bedouins in Qatar, mainly by the famous Danish photographer Jette Bang. In their article titled, “Old Media, New Narratives,” Dr. Jocelyn Mitchell and Dr. Scott Curtis analyze the anthropological photographs of the different expeditions in Qatar.

Figure 1: The Ottoman garrison outside Doha, Qatar, 1904. Photo by Hermann Burchardt, Ethnologisches Museum.

Figure 1 “illustrates a common feature of [anthropological photography in] this style of documentation: to locate and place native peoples in their geographical context. It was an unspoken, even ideological assumption that indigenous peoples were almost an extension of the landscape,” according to Dr. Mitchell. This is to say that photography at the time was mainly concerned with documenting an aspect of life that researchers considered as the subject of their academic findings. As Dr. Mitchell puts it, “The anthropological impulse at this time was to see people as specimens, typical of their race or geography; choices about composition and framing expressed this impulse photographically.”

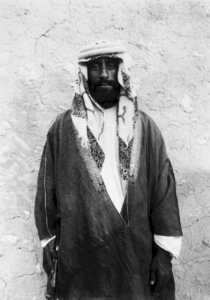

Figure 2: “Genteel Arab,” Qatar, 1904. Photo by Hermann Burchardt, Ethnologisches Museum.

While this approach to photography has changed as the field of anthropology adopted major postcolonial reforms in the late 20th century, it remains that “Anthropology seeks conditions of harsh light…in that anthropologists usually seek to do their work in conditions that are in some sense harsh, so as to expose the raw and elemental, the fundamentals of human nature stripped of the fluff of civilization” according to James Peacock in his book, The Anthropological Lens.

Figure 3: A tobacconist gets a turn at the pipe, Bahrain, 1959 (Adam Wiehe photo/Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 4: Weaving in Bahrain, 1959 (Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 5: An al-Naʿīmī girl, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo/Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 6: Tea time with the Āl Murra, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo/Moesgaard Museum).

Moving away from the anthropological lenses, the crowdsourced digital collection of the Arab Image Foundation illustrates a contrast in the visual representation of the region and its cultures. To start, these collections were submitted or donated to the foundation by family members; therefore, they depict a personal and more intimate aspect to their representation.

Figure 7: Farid El-Atrash and Samia Gamal, Cairo, Egypt (Faysal El-Atrash/Arab Image Foundation).

Figure 8: In the desert between ‘Beit el Hollat’ and ‘El Moussaiab,’ on the road to Iraq, 1939 (Zuhair Izzat Darwazeh/Arab Image Foundation).

Figure 9: A street in Manama on Bahrein Island, Persian Gulf, Manama, Bahrain, 1950 (Arab Image Foundation).

Figure 10: School outing to al-Fintas, Kuwait, 1950 (Abdel Razzak Badran, Arab Image Foundation).

The above photographs illustrate the personal and diversified representation of the Middle East and mark a moment of transition for photography in the region, a moment when the subjects are not observed by external lenses. In this sense, photography took on a more intimate persona where it became an expression of the individuality of the subjects, each with their own style, framing, and clothing. This milestone in modern photography has in turn paved the way for contemporary photojournalism to take on the symbolic aspect of visual representation. For example, Khalil Hamra is a Gaza-based Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist that focuses on the conflict in Palestine and Syria.

Figure 11: A Palestinian man sits on his luggage as he waits to cross to the Egyptian side of the Rafah border crossing, in the Southern Gaza Strip, Saturday, Feb. 11, 2017 (AP Photo/ Khalil Hamra).

Hamra’s photo in Figure 11 represents both the individual struggle of the Palestinian man and symbolizes the struggle of Palestinians in general. This is to say that photography is not only a tool for representation but also a platform for protest and activism. The history of photography in the region thus illustrates how it shifted from being exclusively used as an academic tool by foreign researchers to being a tool of self-expression, and eventually a platform for activism and protest.