By Victoria Ojeda, Slow Food USA network fellow, with guidance from Jim Embry

Black and Indigenous farmers laid the basis for US agriculture and have been at the forefront of sustainability, regenerative agriculture, and preservation of the land. Many of these ancestral techniques have been appropriated by predominantly white sustainable farming communities without recognition, and the whitewashed story of sustainable agriculture does not do justice to the contributions of Black and Indigenous communities.

This month, in honor of Black History Month, Slow Food is highlighting the vast contributions of Black figures who have been integral to the agricultural movement. As a food movement, we need to learn this important history and be committed to telling this history when we tell the story of food and agriculture all year.

Let’s Review

When Europeans forcibly moved Africans to this country, they not only exploited Black labor and livelihood, but also their skills as farmers, seed savers, animal caretakers, herbal healers, and inventors. European settlers relied on the skills of enslaved people for growing crops such as rice and millet. In fact, rice agriculture in the Carolinas depended on the exploited expertise of enslaved West Africans who had a long history of rice cultivation.

Post-enslavement, Black farmers continued to face injustices. Freed Africans were promised forty acres and a mule, an attempt by the federal government to redistribute land, which never materialized. This failure forced Black farmers into sharecropping, another form of labor exploitation where primarily white landowners profited off Black labor in exchange for a meager amount of cash.

Despite laws and racist systems working against them, African-American land ownership was at its peak in the beginning of the 20th century. But racial violence towards Black farmers during the Jim Crow era, along with discrimination in land ownership policies and lending practices contributed to many Black farmers moving North to urban centers as part of the Great Migration.

Today, only a small percentage of Black farmers remain, and less than 2% of arable land is owned by Black farmers (see Vann R. Newkirk II’s article in the Atlantic). Systemic discrimination persists (see this recent NY Times article), with Black farmers obtaining only 0.2 percent of small farmer microloans from the Agriculture Department in 2015. Black-owned farms are disproportionately smaller in size and therefore gain less revenue.

Grassroots efforts to combat past and present injustices are significant. Land trusts, such as New Communities and The Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust aim to address past injustices and reconnect Black farmers to land. A Senate bill, The Justice for Black Farmers Act, intends to support Black farmers through federal land grants. There is still a long way to go in combating this history of land grabbing from BIPOC communities.

Farming is a political act

It’s clear that throughout history, farming is a political act, deeply impacted by policies and societal influences. And it’s equally clear that contemporary sustainable agriculture techniques owe a lot to Black agriculturalists. Our hope is to broaden the awareness of our agricultural ancestors and pay respect to the legacies of Black food geniuses.

Learn more:

- Find books on Black farming and Black agrarian history in the US on our Bookshop.

- Slow Food Equity, Inclusion, and Justice Working Group

- Slow Food Books

- Small and Heritage Black Farmers & Southeastern African American Farmers’ Organic Network (SAAFON)

- Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust

- National Black Food & Justice Alliance

- Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners (BUGS)

- Gullah/Geechee Land & Legacy Fund

- 40 Acres and a Mule Project GoFundMe site

- ‘The Great Land Robbery,’ by Vann R. Newkirk II. The Atlantic, September 29, 2019

- ‘White People Own 98 Percent of Rural Land. Young Black Farmers Want to Reclaim Their Share.’ by Tom Philpott, Mother Jones. June 27, 2020.

- ‘Two Biden Priorities, Climate and Inequality, Meet on Black-Owned Farms,’ by Hiroko Tabuchi and Nadja Popovich. the New York Times, January 31, 2021.

- ‘Booker, Warren, Gillibrand Announce Comprehensive Bill to Address the History of Discrimination in Federal Agricultural Policy,’

- How southern black farmers were forced from their land, and their heritage, PBS

- What Happened to All the Black Farmers?, NBC Left Field

Are we missing resources? Please share them in the comments!

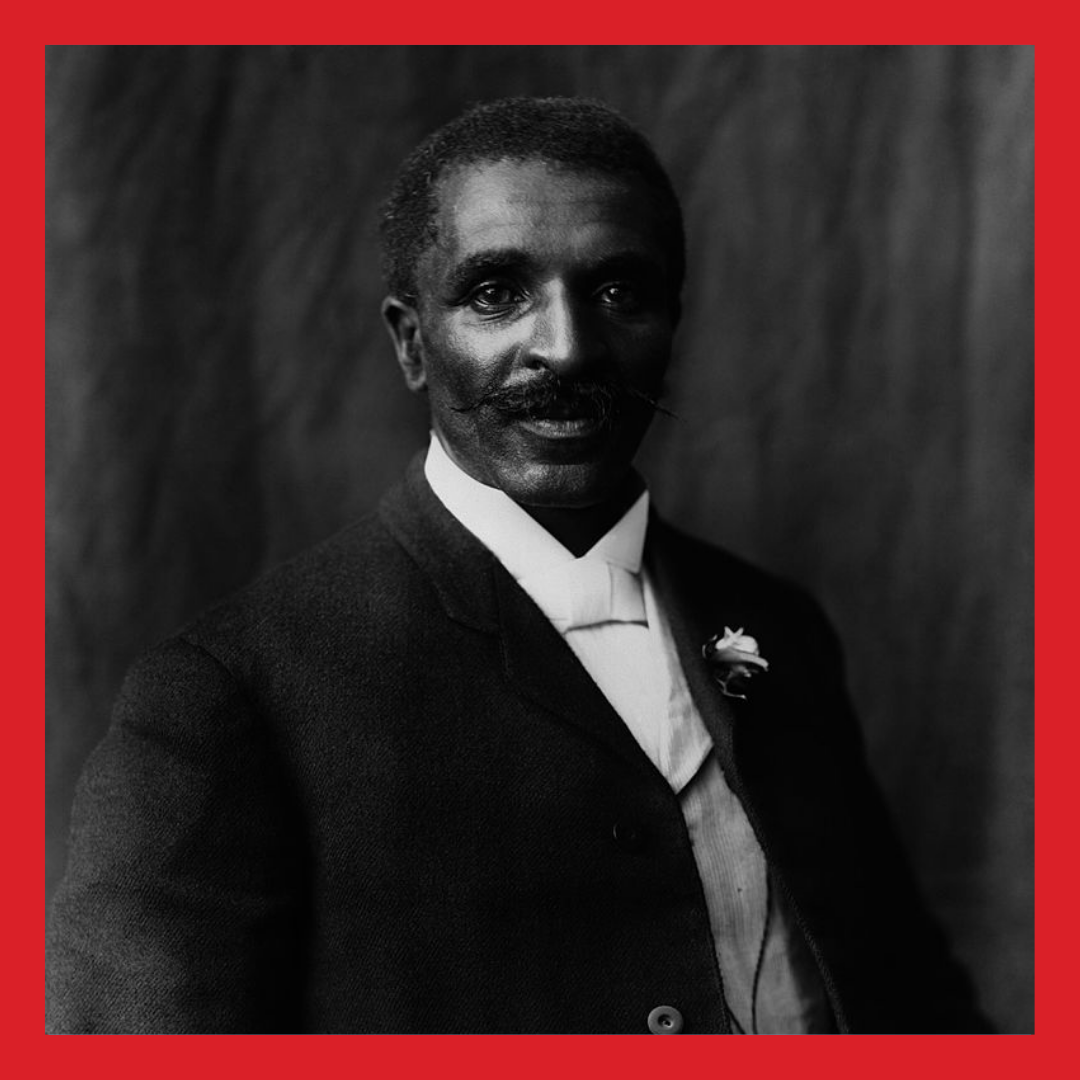

Dr. George Washington Carver

Organic farming and sustainable agricultural practices are an African-Indigenous system developed over thousands of years, and Dr. George Washington Carver is credited with reviving this system in the early 1900s at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Often overlooked in the history of organic farming and sustainable agriculture, Dr. Carver is considered by many to be the father of modern regenerative agriculture in the US.

Realizing that years of monocropping cotton had stripped southern soil of nutrients, Dr. Carver developed a crop rotation method which alternated cotton crops with legumes like peanuts and promoted the practice of composting. These practices brought nutrients back into the soil, revitalizing the land and diversifying the crops for farmers in the south to grow and sell. At the Tuskegee Institute, Dr. Carver educated local farmers, encouraging them to “look at the permanent building up of our soils.” Dr. Carver truly set the stage for the regenerative agricultural practices today.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Renowned activist Fannie Lou Hamer may be less known for her work in food justice, but her contributions to the movement are just as substantial. In 1969 Hamer began the Freedom Farm Cooperative in the Mississippi Delta, a community economic development project for low-income Black farmworkers, providing them with food, employment, housing and education. The FFC aimed to bring agency to Black farmers and their families who had been routinely and systemically denied loans for land, forcing them to find work elsewhere or work in sharecropping. By 1973, the FFC had 600 acres of land, hundreds of families involved, as well as job training, affordable housing, education, health care.

Booker T. Whatley

Booker T. Whatley was a student of George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute and later a professor. He worked to support small farmers and sustain local agriculture, creating a guide called “How to Make $100,000 From a 25-acre Farm.” Whatley encouraged farmers to set up profitable small farms by diversifying crops so they could harvest and generate income throughout the year. Whatley then encouraged farmers to start a membership program where customers could pay a fee to receive a portion of the harvest, a program he called the Clientele Membership Club model. This was the foundation for our modern CSA system.

Shirley Sherrod and New Communities Land Trust

Shirley Sherrod was the co-founder of the grassroots organization, New Communities Land Trust, which has worked for over 50 years to empower Black farmers in the rural South. In 1969, New Communities was established as a farm collective after purchasing nearly 6,000 acres in Georgia. It began as a safe haven for Black farmers and their families who were driven from their land by racist policies and for participating in the Civil Rights Movement. The community envisioned a future of shared stewardship of the land where they could be fully self sufficient. Over time, they successfully farmed revenue-generating crops, as well as operated a farmer’s market, greenhouse, a day care center, and grocery store. In 1985, New Communities lost their land to foreclosure after a severe drought halted their operation. Black farmers were denied emergency loans given to their white counterparts. Years later however, in a settlement from the federal government to compensate Black farmers for years of discrimination, they were able to invest in new land, once owned by the largest slaveholder in Georgia.

Today, New Communities continues to support Black farmers and landowners. They continue to farm and serve as a community space for education and social justice. Their initial vision serves as the framework for the many community land trusts today. Support their work and learn more about them here.

Edna Lewis

Edna Lewis is renown for her work as a chef, restaurant owner, and cookbook author, but in many ways she belongs alongside the other historical figures we have been talking about for Black History Month that created a lasting impact on US agricultural history. Edna’s cooking was famous for her use of fresh, locally sourced foods that highlighted the Southern US, and the foundational impact of African Americans on American cuisine, and our agriculture systems more broadly. All agriculture ends on the table, and Edna was creating new ways of bridging that gap at a time when the concept of farm-to-table was relatively unknown in the restaurant world. By the time she passed at 89, in 2006, she had inspired generations of chefs to cook seasonal, fresh food and to have pride in Southern food heritage and ingredients.

Very interesting. Thank you for including the links on follow up articles and blurbs on the towering pioneers of African American agriculture.

Thank you!!

Thank you for honoring our ancestors in this way. Their knowledge, talents, and passion have gone under-sung for far too long.

It is always a pleasure to read things like this, as it tells us the story of the olden days and how people have survived them. Black people have come along way from apartheid to this now. They deserve all the happiness and rights just like everyone else. Thanks for sharing this article.

Shirley Sherrod was the co-founder of the grassroots organization, New Communities Land Trust, which has worked for over 50 years to empower Black farmers in the rural South. In 1969, New Communities was established as a farm collective after purchasing nearly 6,000 acres in Georgia. It began as a safe haven for Black farmers and their families who were driven from their land by racist policies and for participating in the Civil Rights Movement. The community envisioned a future of shared stewardship of the land where they could be fully self sufficient. Over time, they successfully farmed revenue-generating crops, as well as operated a farmer’s market, greenhouse, a day care center, and grocery store. In 1985, New Communities lost their land to foreclosure after a severe drought halted their operation. Black farmers were denied emergency loans given to their white counterparts. Years later however, in a settlement from the federal government to compensate Black farmers for years of discrimination, they were able to invest in new land, once owned by the largest slaveholder in Georgia.