When the Supreme Court released its opinions this morning on the two Texas cases around S.B. 8—the vigilante bill that allows anyone to collect $10,000 bounties against suspected abortion providers—there wasn’t a lot of clarity or consistency in the news media on how to frame what had happened. Was it a “win” for abortion rights or another warning of the coming blow to abortion access in this country? The court did allow the plaintiff abortion providers to continue to try to bring suits against a handful of state licensing officials tasked with helping to implement the six-week ban, but it declined to enjoin the law, which has prevented virtually any abortions in the state of Texas after six weeks since Sept. 1 and makes no exceptions in cases of rape and incest.

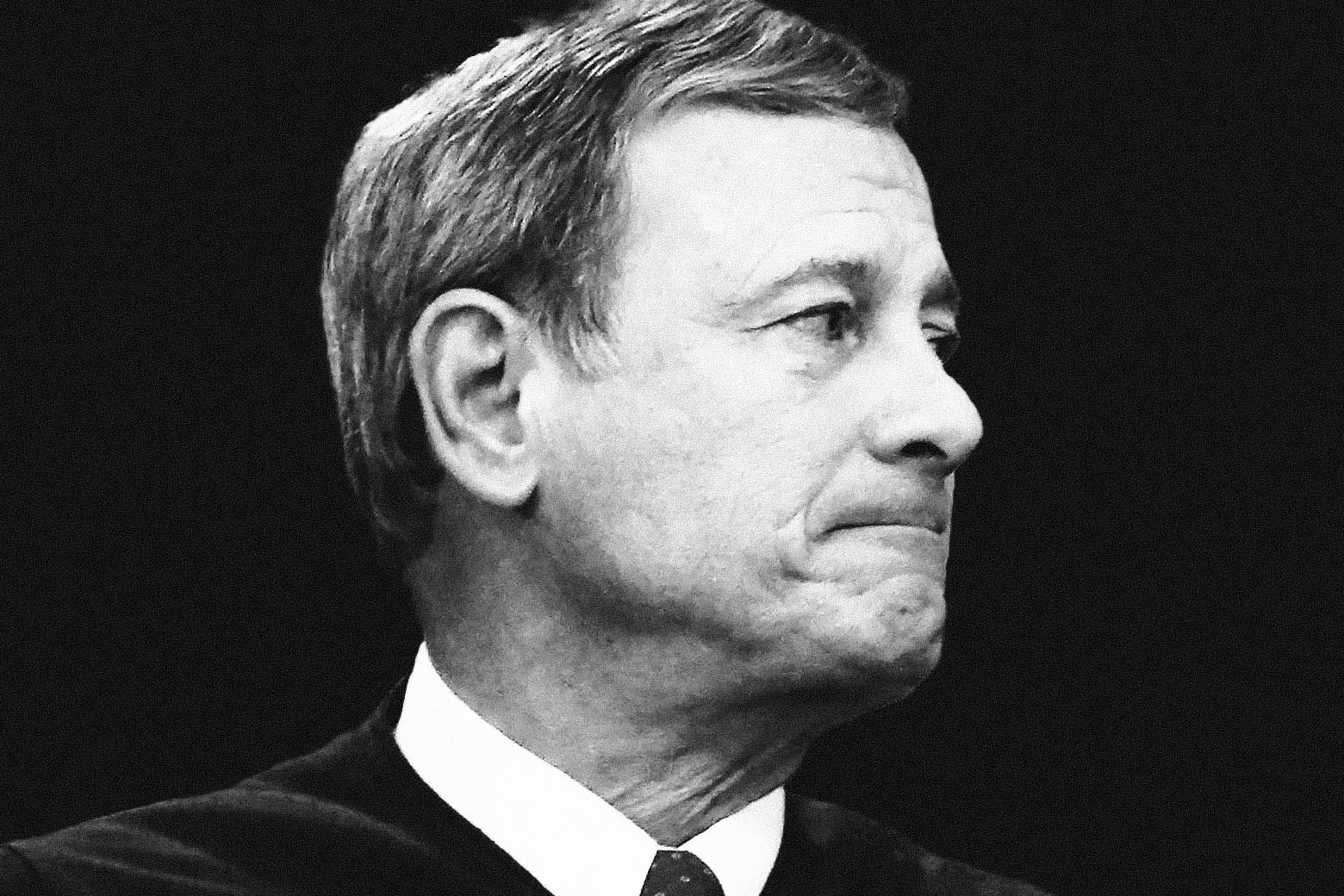

The trouble that the media is having in settling on a coherent frame for this specific decision is both entirely the problem and entirely beside the point. The real story of the two decisions in U.S. v. Texas and Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson is that Chief Justice John Roberts has now lost control of his court. As was the case in the very first shadow docket order that allowed S.B. 8 to go into effect, despite abundant evidence that it was materially harming pregnant people and clearly violated Roe v. Wade, the vote today was 5-4, again with the court behaving as though there is nothing unusual about the Texas scheme. The chief justice had over three months to change a single mind on the conservative flank of the court. He failed to do so. Writing for those five justices, Neil Gorsuch lays out myriad stumbling blocks and problems with the abortion providers’ theory before granting them very limited relief against four state licensing officials who have some authority to enforce S.B. 8.

The chief justice, concurring in part and dissenting in part, pointed out that the purpose of the law was to evade judicial review: “Texas has passed a law banning abortions after roughly six weeks of pregnancy. That law is contrary to this Court’s decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey. It has had the effect of denying the exercise of what we have held is a right protected under the Federal Constitution.” He describes Texas’ enforcement mechanisms as “an array of stratagems, designed to shield its unconstitutional law from judicial review.” He goes on to note that “these provisions, among others, effectively chill the provision of abortions in Texas.” All of these statements are facts. To address the problems they lay out, he would add the attorney general and a state court clerk back to the list of folks who could properly be sued.

The chief justice’s opinion closes with this grim warning:

The clear purpose and actual effect of S. B. 8 has been to nullify this Court’s rulings. It is, however, a basic principle that the Constitution is the “fundamental and paramount law of the nation,” and “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Indeed, “[i]f the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery.” The nature of the federal right infringed does not matter; it is the role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system that is at stake.

His statement is joined by the court’s three liberals.

Perhaps now is as good a time as any to put to rest the soothing notion, floated last spring, of a 3–3–3 court, with a temperate and amiable Brett Kavanaugh as the median justice and a youthful Amy Coney Barrett inclined to pump the brakes on the most radical elements of the Federalist Society’s pet projects. Neither Barrett nor Kavanaugh appears to be swayed by the chief justice’s concerns for institutional legitimacy or even, in fact, institutional supremacy. If red states want to go ahead and choke off federally protected rights, they have been given the comprehensive road map. We will certainly see red states do precisely this.

The mistake we’ve been making for over a year lay in believing that John Roberts’ worries with respect to the reputation, independence, and legitimacy of the court were both an end in themselves and shared by the imaginary centrists Barrett and Kavanaugh. We have for too long confused Roberts’ concern for the appearance of temperate independence (the “lie better next time” instruction to litigants) with a concern for actual temperate independence. Faced with public outcry about the way in which S.B. 8 was handled on its emergency docket in September (in the dark of night, without explanation), the court scheduled real-life arguments and real-life briefings, then waited yet another month, and then somehow produced a decision with substantially the same outcome. This time it came with an elaborate warning to abortion providers that they can go ahead with their lawsuit but they will likely fail again in the future—while the majority still congratulated itself on having treated the plaintiffs with “extraordinary solicitude at every turn.”

I have used up my quota of the word gaslighting for 2021, but to be clear, abortions after six weeks are still unlawful in Texas. Real people are suffering the real consequences, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor opens in her own partial dissent: “For nearly three months, the Texas Legislature has substantially suspended a constitutional guarantee: a pregnant woman’s right to control her own body.” Five conservative justices think this is just fine. Clever, even. The stratagems by which Texas’ abortion ban was diabolically effectuated have been blessed yet again by five justices on the Supreme Court, who tell you once again that this enforcement mechanism was just too brilliantly innovative to be enjoined and possibly even too brilliant to be successfully challenged in the future. And only the chief justice seems to be willing to say that this constitutes “nullification” of a fundamental constitutional freedom, and should perhaps be addressed accordingly.

The problem at the heart of the perception of John Roberts’ moderating influence on the court was that it was always about public perception. When he was still theoretically in charge of the conservative supermajority, his approach was in fact that it could do anything, so long as it didn’t look too radical. Some of us came to confuse that with moderation. But public perception is malleable and can be measured on a sliding scale. Five justices want you to call a narrow loss a “win” for abortion rights, and they want you to think of state nullification as “novel.” They will keep saying that over and over until one concedes that it’s true, and when Dobbs comes down this summer, they will tell you there is nothing radical in doing away with the right to choose. They will assume that if you accepted nullification in September, you’ll be open to overt bans come spring.

Roberts is credited with soothing us that Supreme Court justices are never doing anything more than calling balls and strikes. But under his watch, a conservative supermajority has changed the strike zone, corked the bats, and set the whole infield on fire—all while telling us that the game remains the same. They managed all that with the help of one Chief Justice John Roberts. What this tiny, narrow, wholly radical ruling reveals is that Roberts is now alone in his concern that the fans might soon figure all this out. His problem? He’s not the one calling the game anymore.