Quarantine Could Change How Americans Think of Incarceration

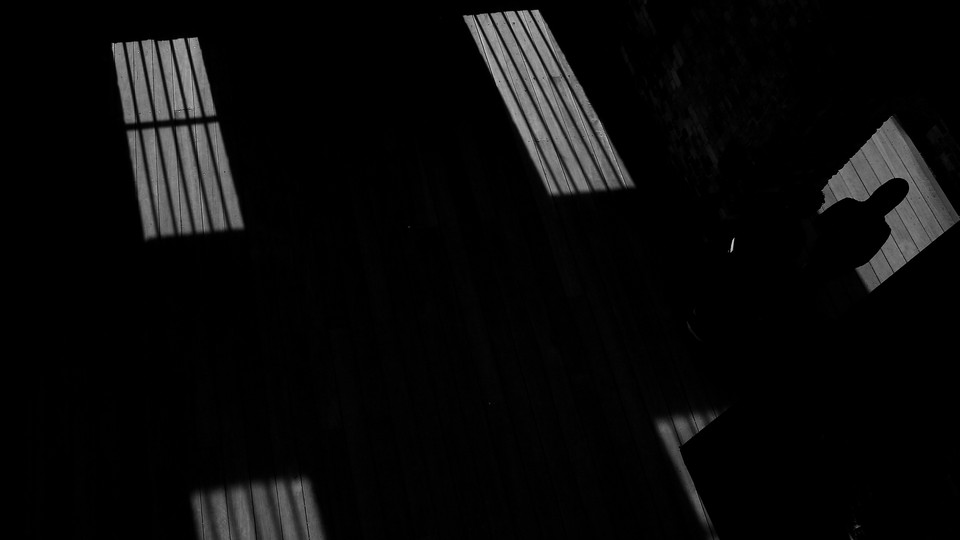

Nationwide forced isolation, along with media coverage of the pandemic’s toll in U.S. jails and prisons, could shift public perceptions of carceral punishment.

Earlier this month, Ellen DeGeneres attracted public ire for something she said during the first “at home” edition of her show. Sitting in one of her palatial houses, the 62-year-old comedian joked that self-isolation is “like being in jail … mostly because I’ve been wearing the same clothes for 10 days and everyone in here is gay.” The video was removed from her YouTube channel following swift backlash, but DeGeneres isn’t the only entertainer who has made glib remarks about quarantining during the coronavirus pandemic. Recently, the Game of Thrones actor Sophie Turner told Conan O’Brien that quarantine is “prison” for her husband, the singer Joe Jonas, because he’s “a real social butterfly.”

In some other climate, these hyperbolic comparisons might simply register as thoughtless. Now, after months of reports chronicling the harrowing conditions in jails and prisons, they come off as particularly callous. Being restricted from public gatherings may be frustrating, but even Turner and DeGeneres would admit that it’s nothing like what correctional facilities face. In Colorado and Louisiana, Illinois and New York, incarcerated people are dying of the virus—sometimes while handcuffed—because jails and prisons are incompatible with the measures required to keep them safe. Social distancing is impossible. Even on a normal day, accessing medical care is a Sisyphean task. Crowded and unhygienic conditions are common. As a result, the infection rates in these institutions far outpace those of even the hardest-hit American cities.

But although the oppressiveness of quarantine and the dangers of incarceration during a pandemic aren’t the same, they’re more related than many might think. The media have widely covered the devastating effects of COVID-19 in jails and prisons, as well as the risks that an outbreak among inmates poses to the surrounding communities. When taken alongside Americans’ experiences with nationwide forced isolation, these facts could change how the public thinks of carceral punishment. Because the coronavirus’s lethality is unprecedented, so, too, are the social-distancing and lockdown measures that are forcing many Americans to experience prolonged confinement for the first time. Following several years of slow, sometimes bipartisan, attempts to reform the criminal-justice system and its reliance on mass incarceration, these powerful new realities could challenge entrenched beliefs about the efficacy—and ethics—of sending people “away.”

While invoking prison to describe quarantining in one’s own home is excessive, such comparisons are often rooted in a desire to express the real pains of isolation. Craig Haney, a psychology professor at UC Santa Cruz, and the author of Criminality in Context: The Psychological Foundations of Criminal Justice Reform, has spent much of his career studying the toll of mandatory social separation—an experience that far more people are beginning to understand, in some small way. When we spoke, Haney emphasized that humans are both socialized and neurologically wired to connect with one another; being deprived of the opportunity to do so has profound consequences. When people complain about quarantine, Haney told me, they’re often alluding to “the inconvenience of it: You can’t go out to bars with your friends, you can’t see your family, you can’t go and do all the fun things.” But, he said, “in addition to being deprived of activities, we’re being deprived of social contact, which is essential to our mental and physical well-being. It’s almost like breathing. You have contact with people all the time, and you only notice it when you don’t have it.”

Even some formerly incarcerated people are drawing parallels between prison and quarantine, albeit in nuanced ways, referencing feelings of anxiety, a lack of control, and scarcity. “At one level, I think [the comparison] is pointing to how painful, actually, the deprivation of liberty can be,” Bruce Western, a sociology professor at Columbia University, told me. “We can think about references to ‘country-club prisons’ and so on, as if the deprivation of liberty was not a ‘real’ punishment. And now we’re all sheltering inside and a lot of people are experiencing this as very, very difficult … But then, of course, the real conditions of incarceration regularly and routinely go well beyond the deprivation of liberty,” he added. “On top of what sociologists have called ‘the pains of imprisonment,’ [incarcerated people are also] facing intense health risks now.” (In addition, adequate psychological services are rarely available for the staggering population of mentally ill people who are routed into the criminal-justice system.)

Of course, social distancing still allows for ample opportunities to connect with others remotely despite physical isolation. In jails and prisons, where visitors are always under heavy monitoring and virtual communication is prohibitively expensive, those options don’t exist. June Tangney, a psychology professor at George Mason University, noted that the disappearance of normal social contact could be a chance for Americans to seriously consider the painful effects that more stringent measures have on incarcerated people: “Maybe that gets us to rethink about the sheer number of people that we’re incarcerating who have either a primary substance-use problem or a primary problem with mental illness,” she said. “And having experienced a little piece of [isolation] ourselves, maybe we’ll be more sympathetic.”

In addition to undergoing quarantine, many Americans are coming to view incarceration through the lens of public health. Even before the virus spread across the country, professionals as disparate as doctors, activists, corrections officers, and health reporters were enumerating the ways that jail, prisons, and detention centers could play host to a “public-health disaster.” This framing acknowledges that inmates’ well-being can directly affect those on the outside, which may prompt people to ask weighty ethical questions about how the penal system treats those behind bars: Does anyone deserve to die because they failed to report to their parole officer or were unable to pay a $500 bond? Does any crime justify a potentially painful, gasping death?

Such considerations are made more urgent by recent developments at jails and prisons. New York City’s Hart Island has long been a public cemetery for the poor or unclaimed. But until earlier this month, the people digging the mass graves for virus victims were bused in from the Rikers Island jail; national media covered their macabre assignment. This burial practice was halted after officials decided that bus rides to Hart, during which inmates sat next to one another, presented too great a viral-transmission risk. (Scientists are still trying to determine whether COVID-19 can be spread by a dead body.)

That grim labor is just one element of the wide-ranging risks facing those incarcerated at Rikers, where the infection rate far outpaces that of New York City writ large. “The last couple of weeks have obviously pressed forward in a very hypercritical way the need for us to decarcerate our jails and prisons—and [to] recognize that even before COVID, health and sanitary conditions in our jails and prisons were abysmal,” says Tina Luongo, the attorney in charge of the criminal-defense practice at the Legal Aid Society in New York, which provides free representation to low-income people. “The fact that [incarcerated people] can’t socially distance—your bathroom facilities are shared by 20, 30 people … Your underlying vulnerabilities [had always been] present, but now they’re life-threatening.”

In growing numbers, people not affiliated with traditional advocacy circles are calling for decarceration, whether through reducing jail and prison populations or easing punitive measures to protect public safety. A couple of weeks ago, dozens of doctors and public-health professionals sent a letter to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention demanding decarceration and expanded access to health care for those who are released. Other doctors signed an open letter to death-penalty states asking them to relinquish the sedatives used during executions, because the supply needed to treat COVID-19 patients is rapidly dwindling. (The letter noted that medical professionals have long criticized states’ practice of stockpiling such drugs, which weren’t developed to help end lives.) These efforts join campaigns such as Free Them All for Public Health and Release Aging People in Prison, as well as writing from legal scholars and city officials, in framing decarceration as necessary for public health and safety. Though often aimed at achieving concrete goals rather than changing public opinion, these efforts may nonetheless sway newly attentive readers.

Jails and prisons aren’t self-contained entities. Though corrections officers are more protected than incarcerated people, they’re at risk too, along with their families and communities. This month, on her free Apple TV+ show about COVID-19, Oprah Winfrey discussed the public-health need for criminal-justice reform, because infections inside prisons can find a way outside as well. “This is why people need to care,” she said, pointing to that link. “’Cause I know a lot of people listen and they go, Well, they’re in jail, and so forget about them.” The coronavirus crisis has brought into sharp relief how interconnected we all are; it’s never been clearer that the country’s fate is bound up in that of its most vulnerable people. COVID-19 is disproportionately killing people in demographics already at greater risk for disease and criminalization: low-income communities, southerners, and black people. (These are also groups most likely to be targeted by discriminatory policing.) Fittingly, “mutual aid” networks, through which communities come together to share resources, have sprung up to address the needs of those hurt both within correctional institutions and outside them.

For the broader American public, the dismissal of incarcerated people’s experiences has really begun shifting—ever so slowly—only in recent years, Haney said. In decades prior, most Americans weren’t critical of such institutions, or of joking references to them. “From the mid-1970s ... until I would say the early 2000s, there was really only one point of view about incarceration, which was The more of it, the better,” Haney said. People outside the system’s grip had “very little awareness of the costs, even the economic costs but certainly not the psychological and the social costs.” That began to change in the early aughts, first with more people expressing ambivalence toward the death penalty and then outright opposition to it. Noting that criminal-justice efforts have become ever more bipartisan, Haney said that he’s seen “people as different as Cory Booker and Newt Gingrich” at related conferences. “There’s now a different kind of awareness, an openness to thinking about incarceration in ways that we didn’t before,” he said.

Consider, for example, the public response to DeGeneres’s remarks about jail. As recently as the early 2000s or the ’90s, “people would've taken that as a joke and treated it as such,” Luongo notes, adding that “the more we talk about the inhumanity of jails and prisons, the more people are becoming aware that that is not the answer.” Some of that recent change in social attitudes is the direct result of various social movements, organizing campaigns, artistic productions, legal battles, and more, sometimes led by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people. The pandemic, and its attendant social-distancing requirements, follows decades of efforts to shift public perceptions about criminal justice—and the legal precedents that shape it.

It’s possible, then, that this widespread isolation might also contribute to different views. Those shifts likely won’t result in the widespread belief that prisons be abolished altogether, and it remains reasonable to ask how we might protect society from grievous crimes. But reducing the country’s reliance on incarceration can take many forms: Already, people new to the decarceration issue are calling for the “compassionate release” of elderly inmates, and those with serious health conditions, for whom COVID-19 would pose the greatest risk. Still others are decrying the institutions’ usage of solitary confinement, sometimes even for children, to slow the virus’s spread. “One of the things that has been so problematic about the era of mass incarceration is that, for most people, prison … is nothing more than an abstraction. It’s a hidden world,” Haney said. “Even if you have a loved one in prison, it’s not something you see directly … I’ve always felt that legislatures who bandy about [sentences of] 10 years or 15 years or 20, who’ve never spent a week in a penal institution, might have a very different perspective if indeed they experienced it directly.”

Quarantine, especially for financially stable households, isn’t a direct counterpart to incarceration: On one side are people who find social distancing tedious or emotionally taxing, and on the other are those for whom the coronavirus is among the most deadly risks. As Western told me, the United States’ response to the pandemic is “really a story about inequality.” Yet there’s something cautiously optimistic about this moment, and what it means for how we all relate to one another. Or, as Haney said, “There’s some reason to be hopeful that if people experience at least a tiny bit of what it is like … to have your day-to-day actions and interactions significantly restricted, that they might get some glimpse of what it is like to be incarcerated, what it is like for people whom we subject to much, much greater deprivations of liberty. Just maybe.”