Colleen Stratton grew up in Kohler, one of the most affluent communities in Wisconsin. She met her trafficker when she was about to turn 25. By then, she'd already struggled with abuse, self-harm and addiction.

She met that man in Florida after her parents sent her there for addiction treatment. Stratton skipped out on treatment and stayed in a beach-side hotel until her money ran out.

Her trafficker, she said, didn't have to groom her. She was already homeless and detoxing from drugs and alcohol.

"He said he was going to take me back to his house and help me get on my feet again," Stratton said. "A week later, he was raping me and having others rape me."

Her trafficker also "owned" four other women and kept them in his "stable" — a term used to describe a group of people being trafficked by the same person.

He would take her to walk the streets, to truck stops and motels.

"I thought that I was just a prostitute," Stratton said. "I literally just thought, 'OK, I'm prostituting myself so that I have a place to stay, so that I can have drugs, so that I don't get beat.'"

Though Stratton didn't realize it, she'd entered the dark world of human trafficking. The International Labor Organization estimated 40.3 million people were victims of trafficking at any given point in 2016. The signs are subtle but it's taking place all around us, in towns of all sizes in Wisconsin.

You may have seen someone being trafficked and had no idea it was going on.

It's not what you think

Women are bound, hands tied with chains or ropes. They look dirty, as if they've been kept in a basement. Some are wide-eyed with fear. Others are stamped with a bar code.

If you type "human trafficking" into an image search on your computer, these are the pictures you will see. The message is clear: Women and children are being sold. They're trapped. These are the makings of a horror film.

But that bar code was edited into the photo. And these are images from a marketing campaign.

Human trafficking in Wisconsin doesn't look quite like this. It looks like the promise of a new career as a model. It looks like an expensive gift to your child from an acquaintance. It looks like a drug addiction and the hope of something more, as it did for Stratton.

Not all trafficking involves sex. A recent example of labor trafficking surfaced in the Milwaukee area where federal prosecutors charged five people in what they called a conspiracy to force Mexican nationals to work on farms in Wisconsin.

It's not the easiest crime to recognize, but human trafficking cases have been documented in each of Wisconsin's 72 counties.

The National Human Trafficking Hotline says it was contacted 122 times about 64 cases in the first six months of 2018 in Wisconsin. Since 2007, the hotline has received 1,523 calls about 362 cases in the state.

Yet no one knows exactly how often people are bought and sold in Wisconsin. Not only do victims sometimes fail to recognize they're being trafficked and the crimes go unreported, but until this year, the state had no mechanism to collect statewide information on trafficking cases, said Derek Veitenheimer from the Department of Justice.

A new data collection process will include more detailed information about each reported incident.

Meanwhile, Sheboygan Detective Tamara Remington speaks to packed rooms of concerned residents when she shares what she's learned working trafficking cases.

The average age for kids is 13 or younger

Remington, like many people familiar with these types of cases, recognizes trafficking as modern-day slavery.

These are very under-reported crimes. Most victims don't self identify, so I really think that the cases that we do see are just the tip of the iceberg.

The U.S. Department of Justice defines human trafficking as a crime involving the exploitation of a person for labor, services or commercial sex.

Up to 80% of recruiting happens on social media, including popular games for kids like Fortnite, Remington says in her community presentations on trafficking. She breaks down the forms trafficking takes: 80% involve sex and 20% labor.

And she talks about who can fall victim to it: just about anyone, as long as they're vulnerable. Traffickers often control their victims using drugs, manipulation and debt bondage.

The average age for boys to be trafficked is around 11 or 12. For girls, it's 12 or 13, she says.

She includes statistics like these in her presentations, but warns they aren't comprehensive and they don't illustrate the nuances of each case.

"These are very under-reported crimes. Most victims don't self identify, so I really think that the cases that we do see are just the tip of the iceberg," Remington said in an interview. "Each case is its own case."

Remington, who was a gang detective in San Jose, California, earlier in her career, said while she's seen some of the hardest gang members turn their lives around, she doesn't see that happening with traffickers.

Joel Urmanski, Sheboygan County's district attorney, said traffickers are "smooth."

"They basically make the victims go down the rabbit hole with them," he said, "so that the victims themselves are either so reliant on their trafficker that they don't want to give the person up, or they feel that they're just equally in as much trouble."

Education and prevention are key, Urmanski said.

If hospital staff know what to look for, they could spot a victim who is branded or recognize that something is wrong when a victim calls a person "daddy" if he's not her biological father. A lack of identification might also be a red flag, Urmanski said. Because many victims are runaways, they might be hesitant to provide their name.

Training officers on what to look for — an unusual number of females in a car, or drugs — can help police identify the crime during traffic stops. Trafficking is a particularly mobile crime, with traffickers often transporting their victims to people who will pay for sex.

"Just because the girls may be contacted or picked up here doesn't mean the trafficking is happening here, too," Urmanski said.

'It's more of mental shackles'

Emmy Meyers is a survivor of sex trafficking. But if you asked her if she had a pimp when she was being sold for sex, she would have said no.

That's what she told the FBI. Not because she didn't have a trafficker, but because she didn't know what she'd been swept into had a name.

Meyers was in an abusive situation when she met a woman who presented herself as a friend. The woman groomed Meyers and encouraged her to move in with the man who would become her trafficker in Milwaukee.

The man promised Meyers safety and love. After she moved in, she said, things were fine for a few weeks, but then "he basically put a loaded gun to my head and said 'You do what I'm telling you to do.'" He threatened to kill her family if she didn't.

This is a label

At one point, her trafficker called her mom to tell her she'd never see Meyers alive again.

Some of the details of that time in Meyers' life are hazy, since she was using heroin — a habit encouraged by her trafficker, who leveraged her addiction, supplying her with drugs after she completed sex acts for money.

But she remembers her trafficker driving her throughout Wisconsin — and across state lines — to be sold for sex.

"There were definitely a lot of times that I had no idea where I was," Meyers said.

She was trapped in the way a lot of victims of sex trafficking are.

"When you see these images of sex trafficking with shackles and handcuffs, they're completely inaccurate," Meyers said. "I wasn't chained somewhere. I could come and go. It's more of mental shackles and manipulation and brainwashing."

In her trafficker, Meyers saw something many victims see: love and stability.

"He was very understanding and charismatic and respectful," she said. "He just appeared to be a wholesome guy."

But Meyers' trafficker took her I.D. and Social Security card and she didn't have a phone she could use without him being there.

Her time in the life ended when she went into a store and stole some minor items.

"Subconsciously, I did it to get caught," she said.

She was interviewed by the FBI, who already had her trafficker on its radar. Her family had also reported her as a missing person.

While she didn't know she was a victim, she said, she knew she didn't want to be doing what she was doing and she didn't want to be on drugs anymore.

At the police station, she met a victim specialist for the FBI and the special agent on her trafficker's case.

"They gave me a way out," she said.

Meyers took advantage of a work release program while in jail. Then she stayed in a shelter, used a transitional program, found a job and saved up for an apartment.

Meyers said recovery has been a long road.

"You don't get out of the life and everything goes away," she said.

But now she runs a nonprofit, Lacey's Hope Project, which is devoted to shedding light on sex trafficking. Meyers gives presentations to schools, churches, police groups and hospitals on what to look for when it comes to sex trafficking.

In her most recent awareness campaign featuring billboards throughout the Milwaukee area, the message is clear: Trafficking can happen to anyone.

And it can happen at a very early age.

They pick up kids from school

Jessica Bitter and Jennifer Matthias of Sheboygan County Health and Human Services have a combined experience of more than 50 years working with at-risk children. They have seen the harm abusive behavior and traumatic experiences can do to children.

Underage victims of trafficking are no exception.

In 2017, four children in Sheboygan County were confirmed to be victims of sex trafficking, and Health and Human Services identified 12 who were at risk. Last year, 18 kids in the county were considered at risk and one was a confirmed victim.

Few kids are trafficked through kidnapping. Instead, most are cases of manipulation. Children think their trafficker is their boyfriend or girlfriend. Even families traffic their own kids.

"Trafficking by force is rare," Bitter said.

Warning signs in children include changes in behavior, new tattoos, constant exhaustion or an older significant other, Matthias said.

Coercion comes with gifts. New items from an older acquaintance could indicate a questionable relationship.

Traffickers are subtle. Trafficking children during the day is much more common and draws much less attention, Matthias and Bitter said. Traffickers can pick up kids during school and get them home for dinner.

Part of the challenge is that the children, like adults, don't see themselves as victims and don't think they've been trafficked.

"They actually think they did it willingly," Matthias said.

To prevent children from becoming victims, parents should monitor their kids' social media use, Bitter said. As long as a kid has access to Wi-Fi, he or she has access to apps traffickers can use to communicate.

Especially at risk are runaways, children with cognitive limitations, the LGBTQ population and those who are truant in school, living in poverty, abused or neglected.

But traffickers can target anyone.

More: Cops send warning to would-be online Johns

'Romeo' and 'Gorilla:' different pimps, same goals

Meyers' trafficker was what law enforcement called a "Romeo pimp." Romeo pimps manipulate their victims in a way that can lead them to believe they care about them. They shower their victims with affection or gifts, but can turn violent and collect on a debt they say their victim owes.

The type of pimp who controlled Stratton was a "Gorilla pimp," someone who uses violence almost exclusively to control their victims.

Both women's pimps used their addictions to take control.

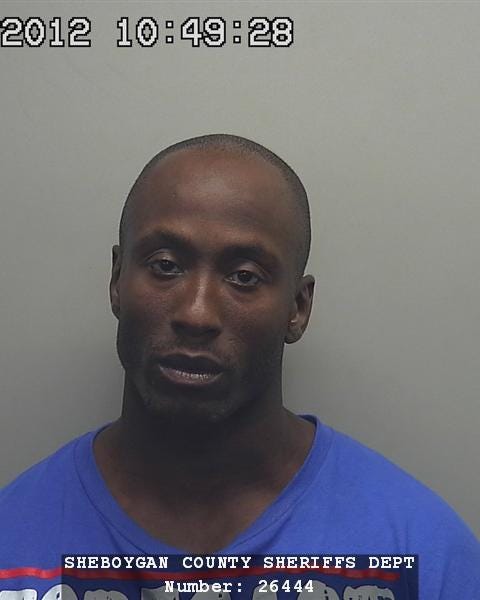

Jason Guidry was considered a Romeo pimp. Friendly and personable, Guidry looked enough like Donald Driver that he would pose for photos as the football star, said Remington, the Sheboygan detective.

At 33, Guidry, a Milwaukee native and Sheboygan resident, was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison for three sex trafficking counts and one count of possession with the intent to distribute heroin in early 2015.

That same year, another trafficker in the Sheboygan area, Pao Chang, was sentenced to 18 years in prison and 15 years of extended supervision for one count of trafficking a child and one count of human trafficking. Two more charges of trafficking a child were dismissed but read into the record.

Chang, a 29-year-old Appleton man, sold underage girls for sex in Sheboygan. Only one of his victims was above the age of 18. While Chang may sound more like a Gorilla pimp, he was still considered a Romeo because he promised his victims love and bonding, Remington said.

Chang starved and dehydrated the girls and gave them methamphetamine, which would allow them to stay awake to have sex dozens of times a night, the detective said.

He mostly took advantage of runaways and promised them the feeling of belonging to a family. He even taught them their own song.

Chang used a 15-year-old girl to reach out to other girls so it would be less suspicious, Remington said. He also took one of the girls to Mall of America only to use it against her, later saying she owed him. These are both tactics commonly used by traffickers.

He would buy the girls lingerie but make them steal things like sanitary napkins from Walmart, Remington said.

Teng Thao, 26, would transport the girls to local hotels, stand as a guard outside the rooms as sex acts took place, and would occasionally find customers, known as "Johns," for Chang. He was sentenced to six years in prison in 2017 for his role in Chang's trafficking operation.

The cases against Chang and Thao began when Chang crashed his car in Clark County with six girls and both traffickers inside.

While these cases seem extreme, they are happening all over the state.

More: 16 arrested in Brown County as part of nationwide human trafficking investigation

'There is life after the life'

Stratton was able to escape her trafficker through Wayside House, an addiction treatment facility near where she lived. She'd made contact with a woman there who ultimately helped her get away.

I could see how I was coerced and manipulated and that it wasn't anything I had chosen.

Because she'd absconded from parole when she left Wisconsin for Florida, she ended up back in jail upon her return.

It wasn't until she was in recovery that she heard the term "trafficking" and realized it applied to her.

"I could see how I was coerced and manipulated and that it wasn't anything I had chosen," Stratton said. "Because for so long I thought I brought that on myself — like that was a choice that I made."

Stratton, now 38 and living in Green Bay, has spoken to groups including police officers, hospital staff and school faculty about her experience. She started working in 2015 with Eye Heart World, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness and working toward the eradication of human trafficking.

In 2017, Eye Heart World opened the Rose Home in Green Bay to help women coming out of trafficking.

One of her favorite things to tell survivors is: "There is life after the life."

Wisconsin groups fight trafficking together

Stratton's sentiment "there is life after the life" is true for many survivors of human trafficking. Throughout Wisconsin, many groups have organized to combat the problem by raising awareness, conducting training and connecting survivors with resources.

Many of these groups work with hotel operators, hospital staffs, police and other people who might be more likely to come in contact with victims.

Dawn Spang, clinical director of Eye Heart World, works with law enforcement officers, who will notify her when they're about to make an arrest so she can make contact with the victims.

Because buyers are typically white men between the ages of 35 and 45 — and so are most officers — it can be intimidating for a survivor to immediately start talking with police, Spang said.

The women Spang makes contact with could end up in Green Bay's Rose Home for treatment in a 14-month program.

Eye Heart World and Rose Home aren't the only organizations raising awareness and helping survivors of trafficking. Throughout Wisconsin, churches and nonprofits have developed programs to confront trafficking and provide resources for survivors.

But all groups say that one of the most valuable tools to combat trafficking is a community that understands what it looks like.

If you need help or know someone who does

Contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 or text them at 233733. A live chat option is also available on their website: humantraffickinghotline.org.

If you need immediate assistance, you can also call 9-1-1.

If you would like to share an experience about human trafficking, contact reporter Diana Dombrowski at ddombrowski@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @domdomdiana