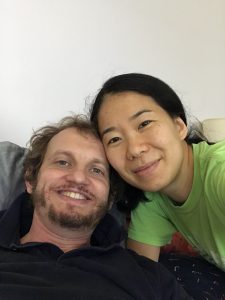

Michael Murphy, MD

Husband and Father,

Neuroscientist and Psychiatrist, Harvard Medical School,

HPV-Attributed Tonsil Cancer Survivor;

Boston, MA

“It was the worst day of my life. The lump had been growing in the back of my mouth for a few weeks. Sometimes it hurt a little bit, but for the most part, I did not notice it,” explained Michael. “I am a doctor and I foolishly prescribed myself antibiotics to make it go away, but they did not help. I tried another course of antibiotics, but the lump kept growing, slowly but steadily. I began to snore and cough in my sleep.”

His wife, May, insisted that he take care of it. Thinking it was just an abscess, Michael went to the Emergency Department to get it drained.

At the ED, the doctor and nurse tried to drain it, but they could not get any fluid. A CT scan and follow-up with an ENT were recommended. At this point, Michael was not yet worried; in fact, he was mostly impatient and eager to get back home.

“I agreed to the CT. CT contrast stings and makes you feel like you have gone to the bathroom in your pants. I eagerly awaited the results of the CT, logging on to my own chart in the hospital’s electronic medical record,” said Michael.

After about half an hour, the results came back with a little red exclamation point next to them. That exclamation point means that something is wrong. Michael opened the report and read “cancer.” Even at this point, he was still in denial and looked up the credentials of the radiologist who read the scan (they were excellent). Michael felt the need to immediately get out of the hospital. The ED doctor kindly, sadly, set him up for a follow-up appointment with the ENT there and he went home. Michael shared the news with May, and they cried together.

The following days were a blur, Michael underwent a biopsy, and while he waited for the results, he read about all the different kinds of cancers he could have. There were so many, and such a wide range of treatments and outcomes, it was hard to know what to expect. Then he received the results: squamous cell carcinoma, HPV+. Although the cancer was on both sides of his neck, it had not metastasized to anywhere in his abdomen.

“In the context of cancer, this is what passes for good news,” said Michael. “I connected with my treatment team at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and began the next phase of my life. We talked about treatment options. I was not a surgical candidate; the cancer was too big and had spread too far for that. The standard treatment for my cancer was seven weeks of radiation and three boluses of cisplatin chemotherapy. It was a rough treatment, designed before HPV had made squamous cell carcinoma spike in young men, but it was still the best we had.”

His treatment team explained the likely side effects. He would lose his beard, his sense of taste, some of his hearing, and most of his energy. Some of these things would return after treatment, but some would never be the same. As a doctor, Michael was concerned about treatment side effects and briefly considered enrolling in a clinical trial that proposed a less severe treatment. His oncologist convinced him otherwise.

There are a lot of things that one must do to get ready for head and neck cancer treatment. Michael had multiple dental appointments. First, to clean his teeth and look for cavities and then to get casts of his teeth made. The casts were used to make little plastic trays that he was to fill with fluoride gel and wear over his teeth for a few minutes each night.

He met with doctors, nurses, social workers, and speech and language pathologists. He remembers getting fitted for his radiation mask. The radiation mask acts to hold a person in place on the table while they are getting radiation. The radiation beams are precisely targeted, and any movement can cause the treatment to be delivered to the wrong tissue. To fit the mask, Michael had to lie on a table with soft, warm plastic pressing down on his face. He had to lie still for about 15 minutes while the plastic slowly cooled and hardened. He has always been a little bit claustrophobic, but meditation helped him get through it.

Michael scheduled his radiation appointments (early in the morning), and chemotherapy treatments. He practiced his swallowing exercises. He also arranged for his colleagues to see his patients during the last weeks of treatment because he was not sure that he would be able to talk then. He explained to his children about his diagnosis and what they might expect to see over the next few months.

Finally, treatment began. Radiation treatment does not take very long. “That first day, I took off my shirt and lay on the table while the technicians screwed my mask over my face. I closed my eyes and meditated. It was over in less than ten minutes. I went home and had breakfast with my family,” explained Michael.

Chemotherapy was different. Chemotherapy took hours. Hours sitting in bed, watching TV and getting up to use the bathroom. During the first treatment, Michael was still able to eat dry hospital sandwiches and drink ginger ale.

Along with the cisplatin, Michael received a high dose of steroids to help get him through the side effects. For the first few hours, he felt fine. But the day after chemotherapy was rough for him. He was nauseous, exhausted, and constantly hiccupping. He drove to an important meeting at work and was barely able to make it home, where he crawled into bed. For him, the chemotherapy always took a few days to recover from.

After a couple of weeks of treatment, Michael began to lose his sense of taste. Sweet flavors went first. He recalls going out for ice cream and not being able to taste it. He had a sweet tooth, so this was a big change for him. His wife made milkshakes and smoothies and tried to coax him to eat. At first, he was able to eat, if not quite as much as he normally did. Eventually, he lost all taste and would get nauseous whenever he even thought of food. Michael knew it was time to have a feeding tube placed.

The day before the procedure, he went to the beach. “I remember swimming in the ocean with my daughter and wondering when or if I would ever be able to do this again,” said Michael.

The feeding tube insertion procedure was quick and relatively painless. After a quick learning curve, he got used to taking four-tube feeds per day and his life even settled into something like a routine. Radiation every day, swallowing exercises, a little work, and a nap. He tried to work in the garden when he could. His beard fell off in patches, which he tried to ignore for far too long. As the treatments progressed, his neck grew redder and tender; chemotherapy weeks were more challenging, and he vomited frequently and suffered from hiccups. He cried sometimes.

And then, one day, Michael had his last treatment. May and their children met him at the hospital with a big sign.

“My five-year-old son was, for some reason, dressed up as Sherlock Holmes,” said Michael. “We celebrated but it felt a little strange to me. Physically, I had never felt worse. I was tired all the time, I still could not eat, and I had developed chronic tinnitus from the chemotherapy. But we pushed on. We went on hikes and bike rides. We celebrated my 40th birthday. I bought myself a large bag of jellybeans and every few days I would try to see if I could taste them.”

Gradually, almost imperceptibly, things began to improve. Michael began to feel stronger. He began to eat again, first a little and then more and more. He was able to get the feeding tube removed. He has had follow-up appointments and repeat scans and so far, everything has been good. One of his doctors told Michael that in ten years he will look back on his treatment as just one terrible summer.

He’s not the same as before. His sweet taste is still diminished, and his energy level is lower. He still has tinnitus and hearing loss and will require hearing aids. His future includes ongoing doctor appointments, scans, and bloodwork. More importantly, Michael no longer takes things for granted. Before he got sick, he never really thought much about dying.

Now, he understands how real death is and how wonderful and brief our time on Earth really is. The recurrence rates for his cancer are low, but they are not zero, and Michael understands that, whether or not his cancer returns, this experience will profoundly shape the rest of his life. “When I was undergoing treatment, I found that first-hand accounts of people with similar cancers were very helpful to hear. I read about a chef with tongue cancer and how it took him over a year to get his taste back. I was connected with a Head and Neck Cancer Alliance Ambassador, and we texted regularly,” said Michael. “As a psychiatrist, I am a firm believer in the power of words and shared stories to help people heal. Now, I would like to be a source of support for other people who have been diagnosed with head and neck cancers.”

To request Michael for your local event, please contact us at info@headandneck.org or complete the online form.