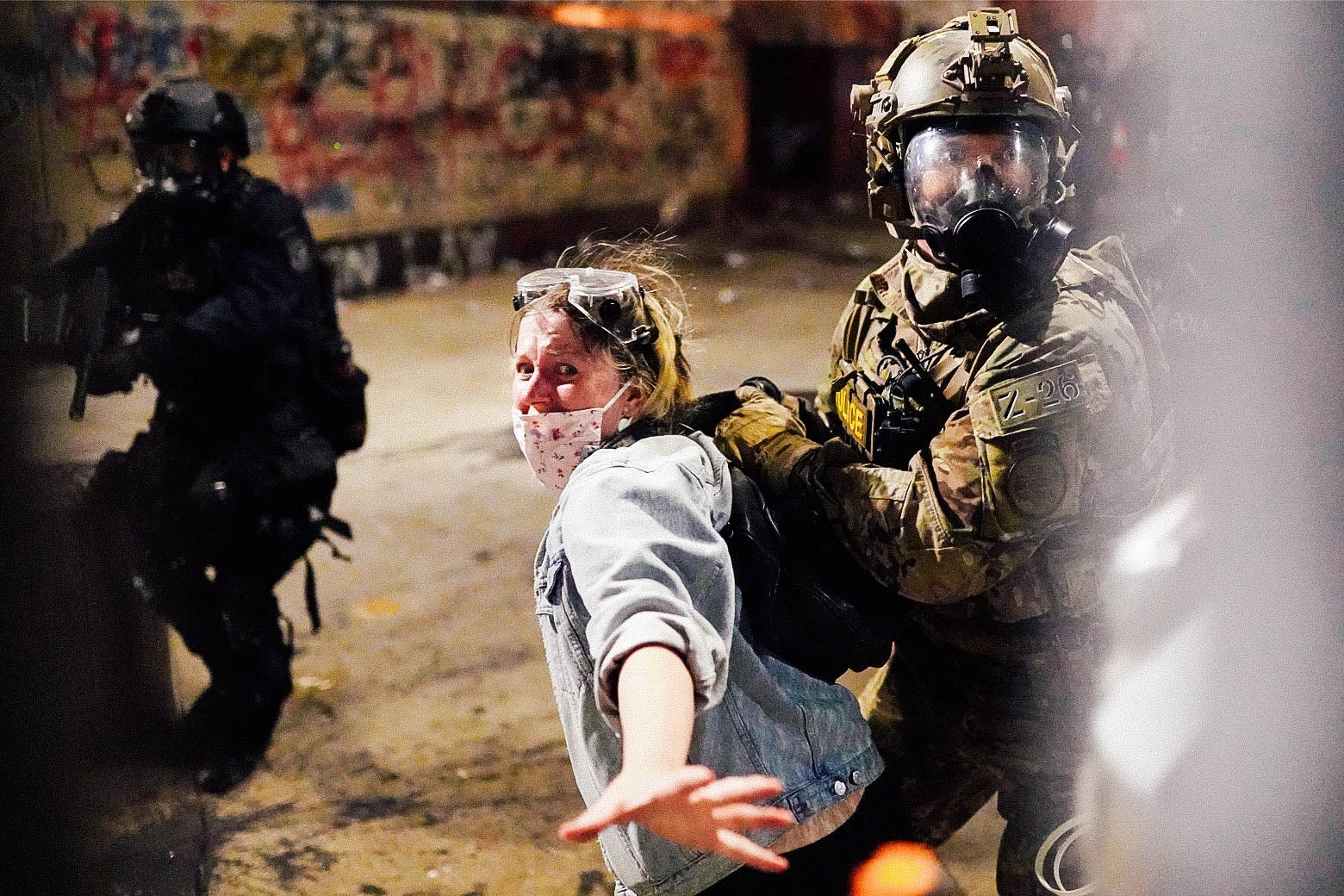

For more than three weeks, federal security forces have been terrorizing protesters in Portland, Oregon. Unidentified agents in unmarked minivans are kidnapping demonstrators without warrants, assaulting journalists, and beating people in the streets. The militarized forces, which have battered crowds with tear gas and “less lethal” munitions, were sent by the Trump administration under the guise of protecting federal property from vandals. The reckless show of force has escalated local tensions: In a video captured by New York Times correspondent Mike Baker on Wednesday night, demonstrators jeered at Mayor Ted Wheeler and called him “tear gas Ted” as he tried to address a crowd. Protesters hold Wheeler, who also serves as the city’s police commissioner, responsible for both the protest crackdowns by the Portland Police Bureau and the continued abuses of federal agents. Wednesday night, some called for him to use the Portland police to protect residents from federal security forces. Wheeler attempted to show that he shared many of their concerns: “We demand that the federal government stop occupying our city,” he said.

There’s a reason why Donald Trump chose Portland as his first major staging ground for this war on journalists and racial justice activists. In the weeks before Trump sent in Department of Homeland Security forces, the Portland police had been making regular use of violent tactics to subdue demonstrators. The Portland Police Bureau has already earned one temporary restraining order from a federal judge for its likely violation of protesters’ free speech rights and another for arresting journalists and legal observers for recording police activity at demonstrations. A few weeks ago, after state officials banned the use of tear gas by police except in the case of riots, the police simply began declaring the protests riots before tear-gassing crowds.

In the PPB, Trump has found a police force fully aligned with his contention that violent shows of force are necessary and warranted to disperse progressive demonstrators. And in Daryl Turner, the president of the Portland Police Association, the PPB’s union, Trump has found a ready ally. Turner has used the language of war to justify the presence of federal agents, saying the city is “under siege.” He’s also publicly denigrated the local elected officials who are calling for Trump to withdraw federal forces from the city: Turner said those leaders are “demonizing and vilifying the officers on the front lines” and “have placed their political agenda ahead of the safety and welfare of the community.”

Jo Ann Hardesty, Portland’s city commissioner and one of the few public officials making bold moves to try to reform policing in the city, has cast blame on both Turner and Wheeler for the federal government’s disregard for protesters’ rights. “I still have to question why was Portland police not protecting Portlanders when these federal goons came in and started attacking us, rather than joining the federal goons who were attacking peaceful protesters,” Hardesty said at Wednesday’s City Council meeting. Earlier this week, Wheeler rejected Hardesty’s request to take over as police commissioner.

Dan Handelman, who co-founded Portland Copwatch in 1992, has followed the department’s recent escalation of violent tactics—and its welcoming of federal security forces—with horror. “In a way, it’s not surprising, because of the history of the Portland police,” he said. “There’s a long history of the police using violence in protests.” Portland Copwatch—a volunteer-run organization that advocates for an end to brutality, racism, and corruption in the PPB—was established, in part, in response to police tactics at a Gulf War protest during a visit from George H.W. Bush. “In breaking up protests, the police brought out pepper spray and used it indiscriminately on the crowds. That was the first time we’d seen that,” Handelman said. His group was also created in response to the Rodney King uprisings and the PPB’s accidental killing of a 12-year-old boy who was taken hostage in the city.

Other incidents of police brutality against protesters followed: In 2004, the city paid a settlement to 12 victims who’d been protesting George W. Bush in 2002 when police began tear-gassing, pepper-spraying, beating, and firing rubber bullets at demonstrators. (An infant was reportedly among those pepper-sprayed.) The plaintiffs in that suit had initially asked for less money in exchange for reforming the PPB’s use-of-force protocols, but the bureau refused.

The PPB’s history of undue violence, which has bred distrust in the communities it’s supposed to protect, extends beyond political demonstrations. Like many police forces, the PPB has a history of officers killing Black people with impunity—including 21-year-old Kendra James, who was killed during a 2003 traffic stop, and 17-year-old Quanice Hayes, who was gunned down while kneeling in 2017. (Black people, who make up about 6 percent of the Portland population, also make up a disproportionate number of those stopped by police and targeted by uses of force.) When the police chief banned chokeholds in 1985 after officers killed a Black man with the hold, officers made T-shirts that said, “Don’t Choke ’Em. Smoke ’Em.” In 2012, the Justice Department reported that the PPB had an unconstitutional “pattern or practice” of using excessive force against people with mental illnesses and has maintained oversight of the PPB since a settlement agreement in 2014. Earlier this year, the DOJ announced that the PPB was finally in compliance with all the requirements of the settlement agreement, though then–police Chief Jami Resch admitted that officers are still shooting people with mental illnesses and will likely continue to do so. “We’re killing more people today with mental health issues by the Portland Police than we did before the DOJ came to town,” Hardesty told Rolling Stone.

In its abuses at protests, the PPB has not targeted demonstrators equally across ideological lines. As alt-right groups emboldened by Donald Trump have gathered in numbers in a state with deep roots in white supremacist organizing, the PPB has been seen as sympathetic to those organizations. A series of friendly text messages sent in 2017 and 2018 showed Lt. Jeff Niiya, the head of the PPB unit that addresses protests, giving protest tips to the leader of the alt-right Patriot Prayer group and congratulating him on his bid for public office. When right- and left-wing groups faced off in 2018, demonstrators observed that police officers faced the left-wing groups and kept their backs toward the right-wingers, though police had found Patriot Prayer members with a cache of weapons on the roof of a parking garage before the protest. (The bureau didn’t inform the mayor of the bust for months.)

The recent clashes are deeply enmeshed in the state’s history. “Oregon really was settled as a white homeland, and that’s why the skinhead groups and the white supremacists, the active white racists, are so strong here,” said Karen Gibson, a Portland State University professor who has studied the Portland police’s history with Black communities. “They’re still quite active here, and this is related to Trump’s whole agenda of reasserting white supremacy,” she said. Since the early 1900s, Portland has also been home to a formidable “strain of revolutionary white folks,” including antifascist and anarchist organizers.

According to activists, the makeup of the PPB is key to its antagonistic relationship with many Portland communities. The force is even more white and less Black than the Portland population, and the Portland Mercury reported in 2018 that just 18 percent of Portland officers live in the city they police. “Growing up in Oregon, in a place that’s 90 percent white, it’s only if you live in the city that you’re going to get exposed to and have experience with Black people and brown people,” Gibson said of the backgrounds of Portland cops. “And you can live in the city on the southern side of town and it’s still nearly 90 percent white. What it means is that [these] whites are unexposed to and unfamiliar with Black culture and Black people.”

“When we talk about how it seems like they’re an occupying force—well, there’s a reason for that, because only 1 of every 5 or 6 officers lives in the city,” Handelman told me.

Unsurprisingly, the PPB’s union doesn’t seem too upset about the current federal occupation. Recent police chiefs have made a habit of ignoring or explicitly violating the mayor’s wishes, including those that govern the policing of political demonstrations. Now, PPA’s Turner is the one going rogue. Wheeler, Multnomah County Sheriff Mike Reese, and PPB Chief Chuck Lovell declined to meet with Chad Wolf, the acting secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, when he came to town last week, but Turner was all ears. He was the only person from the PPB at a meeting with federal law enforcement officials last Thursday, the Portland Mercury reported, and only faults DHS for failing to coordinate with local police. While Portland’s elected officials try to assert the city’s right to police itself, Turner wants to work with Trump’s forces: When he met with Wolf, he told the Mercury, “The basic idea was to go and listen to see if there were any ideas in there that were helpful for us.”