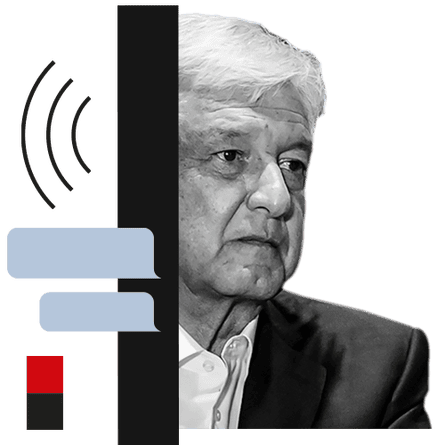

At least 50 people linked to Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador – including his wife, children, aides and doctor – were included in a leaked list of numbers selected by government clients of the Israeli spyware company NSO Group before his election.

Politicians from every party, as well as journalists, lawyers, activists, prosecutors, diplomats, teachers, judges, doctors and academics, were also among more than 15,000 individuals selected as possible targets for surveillance between 2016 and 2017, according to an investigation by a collaboration of international media outlets including the Guardian.

The extraordinary number of Mexican numbers in the leaked data – including phones belonging to priests, victims of state-sponsored crimes and the children of high-profile figures – severely undermines NSO’s claims that its hacking software is only used by its clients to fight serious crime and terrorism.

Quick GuideWhat is in the Pegasus project data?

Show

What is in the data leak?

The data leak is a list of more than 50,000 phone numbers that, since 2016, are believed to have been selected as those of people of interest by government clients of NSO Group, which sells surveillance software. The data also contains the time and date that numbers were selected, or entered on to a system. Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit journalism organisation, and Amnesty International initially had access to the list and shared access with 16 media organisations including the Guardian. More than 80 journalists have worked together over several months as part of the Pegasus project. Amnesty’s Security Lab, a technical partner on the project, did the forensic analyses.

What does the leak indicate?

The consortium believes the data indicates the potential targets NSO’s government clients identified in advance of possible surveillance. While the data is an indication of intent, the presence of a number in the data does not reveal whether there was an attempt to infect the phone with spyware such as Pegasus, the company’s signature surveillance tool, or whether any attempt succeeded. The presence in the data of a very small number of landlines and US numbers, which NSO says are “technically impossible” to access with its tools, reveals some targets were selected by NSO clients even though they could not be infected with Pegasus. However, forensic examinations of a small sample of mobile phones with numbers on the list found tight correlations between the time and date of a number in the data and the start of Pegasus activity – in some cases as little as a few seconds.

What did forensic analysis reveal?

Amnesty examined 67 smartphones where attacks were suspected. Of those, 23 were successfully infected and 14 showed signs of attempted penetration. For the remaining 30, the tests were inconclusive, in several cases because the handsets had been replaced. Fifteen of the phones were Android devices, none of which showed evidence of successful infection. However, unlike iPhones, phones that use Android do not log the kinds of information required for Amnesty’s detective work. Three Android phones showed signs of targeting, such as Pegasus-linked SMS messages.

Amnesty shared “backup copies” of four iPhones with Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto that specialises in studying Pegasus, which confirmed that they showed signs of Pegasus infection. Citizen Lab also conducted a peer review of Amnesty’s forensic methods, and found them to be sound.

Which NSO clients were selecting numbers?

While the data is organised into clusters, indicative of individual NSO clients, it does not say which NSO client was responsible for selecting any given number. NSO claims to sell its tools to 60 clients in 40 countries, but refuses to identify them. By closely examining the pattern of targeting by individual clients in the leaked data, media partners were able to identify 10 governments believed to be responsible for selecting the targets: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, India, and the United Arab Emirates. Citizen Lab has also found evidence of all 10 being clients of NSO.

What does NSO Group say?

You can read NSO Group’s full statement here. The company has always said it does not have access to the data of its customers’ targets. Through its lawyers, NSO said the consortium had made “incorrect assumptions” about which clients use the company’s technology. It said the 50,000 number was “exaggerated” and that the list could not be a list of numbers “targeted by governments using Pegasus”. The lawyers said NSO had reason to believe the list accessed by the consortium “is not a list of numbers targeted by governments using Pegasus, but instead, may be part of a larger list of numbers that might have been used by NSO Group customers for other purposes”. They said it was a list of numbers that anyone could search on an open source system. After further questions, the lawyers said the consortium was basing its findings “on misleading interpretation of leaked data from accessible and overt basic information, such as HLR Lookup services, which have no bearing on the list of the customers' targets of Pegasus or any other NSO products ... we still do not see any correlation of these lists to anything related to use of NSO Group technologies”. Following publication, they explained that they considered a "target" to be a phone that was the subject of a successful or attempted (but failed) infection by Pegasus, and reiterated that the list of 50,000 phones was too large for it to represent "targets" of Pegasus. They said that the fact that a number appeared on the list was in no way indicative of whether it had been selected for surveillance using Pegasus.

What is HLR lookup data?

The term HLR, or home location register, refers to a database that is essential to operating mobile phone networks. Such registers keep records on the networks of phone users and their general locations, along with other identifying information that is used routinely in routing calls and texts. Telecoms and surveillance experts say HLR data can sometimes be used in the early phase of a surveillance attempt, when identifying whether it is possible to connect to a phone. The consortium understands NSO clients have the capability through an interface on the Pegasus system to conduct HLR lookup inquiries. It is unclear whether Pegasus operators are required to conduct HRL lookup inquiries via its interface to use its software; an NSO source stressed its clients may have different reasons – unrelated to Pegasus – for conducting HLR lookups via an NSO system.

Contracts with NSO would be likely to have cost hundreds of millions of dollars, in a country where about half the population lives in poverty.

“Mexico’s capacity to spy on its citizens is immense. [And] it’s extremely easy for the technology and the information obtained through the spyware to fall into private hands – be it organised crime or commercial,” said Jorge Rebolledo, a Mexico City security consultant. “What we know about is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The data leak is a list of more than 50,000 phone numbers that, since 2016, are believed to have been selected as belonging to people of interest by government clients of NSO Group.

While the leak indicates phone numbers that were targeted for potential surveillance by NSO’s Pegasus clients, it is not possible to say whether phones were successfully infected with the spyware without forensic analysis of each device. But technical analysis of more than 37 phones from around the world whose numbers were included in the data found evidence they were breached using Pegasus spyware.

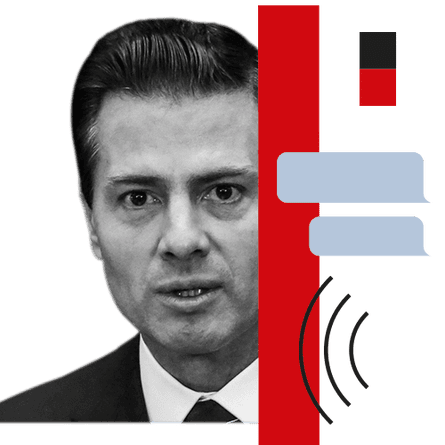

The records cover a period towards the end of one of the most scandal-ridden Mexican administrations in recent history. At the time, the then president, Enrique Peña Nieto, and his Institutional Revolutionary party (PRI) were tanking in the polls.

The findings reflect warnings from security experts that cybersurveillance is unregulated and out of control in Mexico – a country where federal and state governments have long used informants, infiltrators and listening devices to monitor and repress dissent.

Mexico was the first country in the world to buy Pegasus from NSO and became something of a laboratory for the spy technology, which at the time was in its infancy.

The defence ministry was the first to acquire the spyware in 2011 – five years after the armed forces were deployed in the “war against drugs”. When the deal was made, Mexico’s police, army and navy had already been implicated in systematic human rights abuses including torture, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

Other Mexican agencies that bought and/or operated Pegasus include the attorney general’s office and the national security intelligence service (Cisen). Several state security forces are also believed to have access to the spyware, and pervasive corruption has prompted concerns that it could end up in the wrong hands.

In 2012, Peña Nieto, a young, well-groomed politician touted as a reformer, beat López Obrador, the former mayor of Mexico City, to return the PRI to power after a 12-year hiatus.

Peña Nieto promised to take Mexico to its rightful place on the world stage. But a string of corruption scandals, human rights abuses and cover-ups soon tarnished his reputation. Meanwhile, López Obrador, known as Amlo, was already planning another run for the presidency – and his party, the National Regeneration Movement (Morena), was gaining ground in local elections.

As Amlo crisscrossed the country campaigning, however, NSO’s Mexican clients selected almost everyone in his inner circle as persons of interest – including his wife, three sons, three brothers and two former chauffeurs, according to analysis of the leaked data. Amlo rarely used his own phone, relying instead on those of his assistant and communications chief – both of which were selected. His chief of staff, Alfonso Romo, his legal counsel, Julio Scherer Ibarra, and his communications coordinator, Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, were also selected.

Even the manager of the amateur baseball team Amlo plays in was selected – as was his cardiologist, Patricio Heriberto Ortíz Fernández.

Amlo had surgery in 2013 following a heart attack at the age of 60, after which his health became the subject of press speculation casting doubt over his ability to govern. “The only target was the candidate; I was a tool,” said Ortíz, who added that he never discussed Amlo’s health on the phone. “I think it’s very serious, but it was the way things were going on in the country. Unfortunately, I’m not surprised.”

Dozens of national and local Morena figures were also selected by NSO’s Mexican clients, including Claudia Sheinbaum, who later became the mayor of Mexico City. It is unclear how many phones were actually targeted or successfully infected, but private conversations – including one between Amlo’s son and a senior party official – were frequently leaked to the media.

“I always thought the old regime was spying on us for political purposes,” said Sheinbaum when informed about the targeting. “Political espionage was used as a form of persecution, [which] is illegal. Today intelligence is used to reduce violence and crime in a legal way.”

Mexican agencies sought to target politicians from every party – including the governing PRI – with Pegasus. Remarkably, the leaked data suggests that at least 45 current and former governors of Mexico’s 32 states were candidates for surveillance over the two-year period.

“Gathering intelligence is rarely about applying the law in Mexico. It’s about obtaining information that can be acted upon if and when politically beneficial,” said Erubiel Tirado, a security analyst.

Also selected was Peña Nieto’s predecessor, Felipe Calderón, as well as his wife, Margarita Zavala.

Zavala recalls receiving suspicious text messages after announcing her own run for the presidency, but no longer has access to that mobile phone for forensic analysis that would establish if she had been successfully hacked. The data shows that she and members of her campaign team were selected in 2017 by more than one NSO client.

“Under Peña, the use of Pegasus went wild,” said Guillermo Valdés Castellanos, the head of Cisen from 2006 to 2011. “Technology like Pegasus is very useful for fighting organised crime, but the total lack of checks and balances means it easily ends up in private hands and used for political and personal gains without accountability.”

By this time, the attorney general’s office and Cisen were also operating Pegasus. According to intelligence officials, the spyware’s popularity was also rising at the state level, partly thanks to a burgeoning black market.

The leaked data shows that criminal suspects and allegedly corrupt officials – including lawyers of high-profile narcos and disgraced state governors – were selected as targets. But so were victims of some of the biggest scandals that engulfed Peña Nieto’s government.

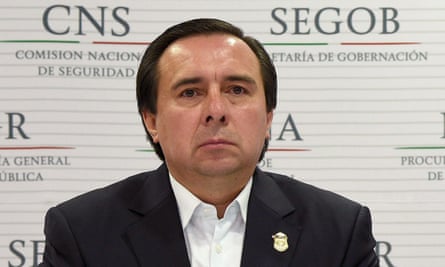

The most damaging was the horrific case of 43 disappeared students, which implicated powerful institutions and political figures including Peña’s close ally Tomás Zerón, the director of the attorney general’s criminal investigation agency (AIC) – and a signatory of Pegasus contracts.

Ayotzinapa

On 26 September 2014, 43 young men from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college in Guerrero state were abducted by police officers colluding with a local crime faction. Afterwards, the government repeatedly lied about the events of that night, including the potential involvement of the local army battalion. The remains of three students were eventually found, but the rest remain missing.

Amid growing outcry, the government was forced to accept an international investigation by a team of experts with diplomatic status, known as GIEI. Citizen Lab, a research unit at the University of Toronto, previously revealed that a phone belonging to the group was targeted by Pegasus in March 2016, after GIEI condemned government interference.

The leaked data seen by the Pegasus project shows that at least one other GIEI phone was selected as a candidate for surveillance, as were those belonging to relatives of at least three of the victims.

They include Melitón Ortega, the uncle of 19-year-old Mauricio Ortega, who became a spokesperson for the families as they campaigned for justice. “The government used this technology to intimidate, control and repress people demanding justice. It is just the latest repressive tool used by the state to violate our human rights,” he said.

As details of the state’s role in the attack and cover-up emerged, the director and lawyer of a human rights nonprofit group representing families of the victims were also selected by the armed forces and Cisen, analysis of the information suggests.

The lawyer, Vidulfo Rosales, said: “[The government] felt pressure and began a smear campaign against experts, parents and representatives of the GIEI … They tried to tap my phones and misrepresented many conversations, making them public to discredit the work we were doing.”

No one has been successfully prosecuted over the disappearance of the students.

Zerón, the head of the criminal investigation agency, was forced to resign after video emerged of him torturing suspects and GIEI accused him of tampering with evidence – but he soon landed a new job as Peña Nieto’s security adviser.

Under pressure over Ayotzinapa, Peña Nieto tried to change the narrative by pushing through what was supposed to be his flagship policy: education reforms.

Teachers

Soon after taking office, Peña Nieto unveiled an ambitious programme to improve school standards and crack down on corruption in the teachers’ union.

Reforms were desperately needed: Mexico was ranked last in education among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, but teachers widely opposed the proposals.

The Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE), a branch of the main union, was at the forefront of organising strikes across the country. Unlike the powerful leaders of the main union, the CNTE had a reputation for probity, yet the Mexican government selected dozens of its organisers with Pegasus between 2016 and 2017.

Q&AWhat is the Pegasus project?

Show

The Pegasus project is a collaborative journalistic investigation into the NSO Group and its clients. The company sells surveillance technology to governments worldwide. Its flagship product is Pegasus, spying software – or spyware – that targets iPhones and Android devices. Once a phone is infected, a Pegasus operator can secretly extract chats, photos, emails and location data, or activate microphones and cameras without a user knowing.

Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit journalism organisation, and Amnesty International had access to a leak of more than 50,000 phone numbers selected as targets by clients of NSO since 2016. Access to the data was then shared with the Guardian and 16 other news organisations, including the Washington Post, Le Monde, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung. More than 80 journalists have worked collaboratively over several months on the investigation, which was coordinated by Forbidden Stories.

It is unclear how many of their phones were eventually targeted or successfully hacked, but Rubén Núñez and Francisco Villalobos, union leaders from the state of Chiapas, were arrested shortly after being selected as targets in June 2016. Teachers and students set up roadblocks across several states, demanding their release.

In response, the government deployed hundreds of armed police to remove unarmed protesters, which left eight people dead and more than 100 injured, including 35 children.

Scores more union activists were selected until mid-2017, some of whom were also later arrested. Analysis suggests it was Cisen, part of the interior ministry, which sought to target the union activists. Núñez and Villalobos were freed, and then targeted again a few months later.

“At the time, the interior ministry said that they could locate us whenever they wanted … many of my colleagues changed their numbers. We were scared for our families,” said Villalobos.

Peña Nieto’s interior minister, Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, told the Pegasus project that during his term of office the interior ministry “never, never authorised or had knowledge or information that Cisen owned or acquired the Pegasus hacking kit, and never authorised anything to do with hacking”.

Peña Nieto is believed to be living in Spain. The Guardian attempted to contact him through the PRI, his former cabinet ministers and staff, his former lawyer, the Mexican embassy in Madrid, his adult children and his girlfriend, but received no response. In 2017, he said Pegasus was being used only to fight organised crime and keep society safe, and denied journalists or activists were targeted.

Amlo declined to comment, but has previously said his government did not use Pegasus.

NSO Group said in a series of statements that it rejected “false claims” about the company and its clients, and said it did not have visibility over its clients use of Pegasus spyware. It said it sold the software only to vetted government clients, and that its technology had helped to prevent terrorism and serious crime.

Following the launch of the Pegasus project, Shalev Hulio, the founder and chief executive of NSO, said he continued to dispute that the leaked data “has any relevance to NSO”, but added he was “very concerned” about the reports and promised to investigate them all. “We understand that in some circumstances our customers might misuse the system,” he said.

A spyware boom

NSO’s technology is not alone in Mexico. The country’s 15-year war on drugs has coincided with a surveillance boom in which as many as two dozen companies are believed to have sold spyware to federal and state agencies.

“No one knows how many sets of espionage equipment there are in the country, or who operates them,” said a former senior security official.

NSO secured its position at the forefront of the market thanks to support from Zerón in the attorney general’s office.

After Peña Nieto left power, Zerón was charged with offences including embezzling of $50m in state funds, forced disappearance and torture linked to the Ayotzinapa investigation. Last year, he fled to Israel – despite the country’s strict Covid travel ban at the time – and claimed asylum. Mexico does not have an extradition treaty with Israel, but officials say Interpol has issued an arrest warrant. Zerón denies wrongdoing and claims the charges against him are political motivated.

Billions of dollars have been spent on weaponry and surveillance equipment, supposedly to combat the drug cartels.

But the supply and demand for illegal drugs continues, and so does the violence and misery. Since the war on drugs began in 2006, more than 300,000 Mexicans have died and more than 80,000 are missing. The morgues and cemeteries are filled with tens of thousands of unidentified bodies. Almost 100 people are being murdered every day.

Mathieu Tourliere and Juan Omar Fierro (Proceso); Mary Beth Sheridan (Washington Post); Paloma Dupont de Dinechin (Forbidden Stories); Lilia Saúl (OCCRP); Sebastián Barragán and Carmen Aristegui (Aristegui Noticias) contributed to this story.