A proposed sprawling petrochemical complex in southern Louisiana will be built on land holding historic cemetery sites that experts believe were likely slave burial grounds, according to documents released Wednesday.

The $9.4bn plastics complex, named the Sunshine Project, is being proposed by Taiwanese petrochemical company Formosa Plastics and would consist of 14 separate plants across 2,300 acres of land in Saint James parish. If approved, it would be allowed to roughly double the amount of toxic emissions in the parish annually.

The project is opposed by a group of community activists in the majority African American parish, who argue the emissions would prove an intolerable health risk. The revelations on the site’s historic significance has further angered residents, many of whom trace their ancestry back to enslavement in the region.

The discovery of slave burial grounds on industrial land in the heavily polluted region between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, known colloquially as “Cancer Alley”, has happened in the past. But the revelations are likely to intensify the fight in one of the most contentious new developments in the region.

Sharon Lavigne, a resident opposed to the development, said the discovery of the cemeteries was “gut-wrenching” and made the proposed site “hallowed ground”.

“I have buried so many family members and friends who have died from cancer. Our community cannot handle another chemical plant,” Lavigne said.

Formosa is currently navigating the approval process with state authorities and as part of this quietly commissioned archaeological research on the land earmarked for development.

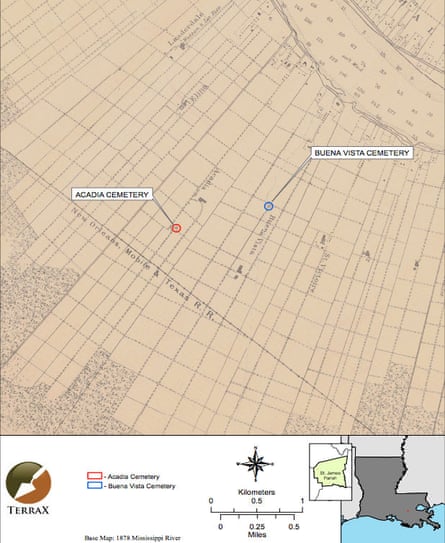

Although initial cultural surveys conducted by the company in 2018 had indicated there were not historically significant sites on the land Formosa plans to build on, the company were later alerted to maps from the late 19th century – submitted to the state’s division of archaeology by an independent researcher – that indicated two cemeteries tied to old plantations on the land.

According to hundreds of pages of emails, reports and surveys released under freedom of information laws to lawyers working for community activists and reviewed by the Guardian before publication, Formosa has found one of these sites, the Buena Vista cemetery, is still intact.

Any evidence of the other, listed as the Arcadia cemetery, could not be located by excavators working for a contractor, who believe that either any human remains or other physical signs of grave sites have been destroyed by construction carried out by previous land users or that the cemetery may never have existed.

A detailed report, filed to authorities in June 2019, suggests “it is possible that slaves who once lived on the property [Buena Vista] might be buried at this location”. Excavation found “human remains and evidence of grave shafts” at the site. An official at Louisiana’s office of cultural development, who was not authorised to talk publicly about the finding, told the Guardian that the positioning of the Buena Vista burial site, away from the former plantation home, indicated its use as a slave burial ground.

It was still unclear how many bodies were held in the graveyard, about an acre in size. Historical records of the lives and deaths of the millions of people enslaved in the United States are scant and often non-existent.

The Buena Vista site sits in a so-called project “buffer zone”, meaning no construction is planned there, despite Formosa owning the land.

Janile Parks, director of community and government relations for the Formosa project, said the company has now “fenced in the identified area to protect it”. She added that Formosa had “conducted archival research and has not been able to connect the plot to anyone or any particular event”.

She said: “As the project progresses, Formosa will follow all applicable state and federal laws in regards to the burial ground and public notification.”

Internal emails suggest that the Arcadia site posed more of an issue to the Formosa project as the old maps indicated it sat directly underneath an area proposed for construction.

Lawyers working for Formosa acknowledged in August 2018 that if human remains were recovered at this site the company “could choose to protect the area from any further construction disturbance with a fence and plaque” but noted that this “would mean that portions of the planned utilities plant may have to be relocated” a move that would be “a very difficult option”. The emails indicate that Formosa favored removing remains and relocating them to another cemetery. Contractors later recovered no remains from the site.

It is expected that Formosa will continue its construction plans with this site, a state official said.

Residents in St James expressed frustration that Formosa did not notify community members about the discovery of the sites, particularly before the parish council approved permits in December 2018.

“They [Formosa] would have first learned that these sites could have been located in late July 2018,” said Pam Spees, a senior attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights, a non-profit legal advocacy group representing Rise St James, a local advocacy group . “But there has been no communication to Rise St James or other community groups about it.”

Formosa said it had “conducted all field work in coordination with the appropriate agencies” including the State Historic Preservation Office. It described the review as a “lengthy and regulated process”.

Lavigne, the founder and president of Rise St James, argued that the cemetery revelations should thwart the Formosa project entirely.

“I feel like God is answering my prayers,” said Lavigne. “This will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.”

She said the group plans to use the new information on potential slave burial sites to ask the parish council to reconsider permits already approved for the Formosa project.

Still, it’s unlikely the grave sites will seriously impact Formosa’s progress, state officials said.

Greg Langley, press secretary for the Louisiana department of environmental quality (LDEQ), a state permitting agency, said he couldn’t comment specifically on outstanding permits for Formosa. But he said: “Normally this type of situation would not affect the permits.”

Formosa is awaiting a decision from LDEQ on its proposed air permit before it can begin construction.

Spees, meanwhile, highlighted the need for a more thorough investigation of historical assets on the land as industrial development continues to grow in Cancer Alley.

“They are putting these industries on land where we know there are people buried,” she said. “How many have already been destroyed along this stretch? What do we need to do to really acknowledge and preserve and protect these types of burial sites?”