Chinese in Southern California are sympathetic, worried for protesters back home

Zi Yuen has been taking her lunch breaks later to coincide with morning in Beijing.

She scrolls through WhatsApp and WeChat messages on her iPhone, looking for the latest news about the protests that have erupted in cities across China, where people are increasingly frustrated after nearly three years of extreme COVID-19 prevention measures.

As she ate a pork floss bun in Rowland Heights on Tuesday afternoon, Yuen credited the Chinese government with keeping the coronavirus under control. But she understands why protesters are taking to the streets.

“I don’t know how long the state and the government think these lockdowns can go on,” said Yuen, 33, a software developer from Beijing who moved to the Los Angeles area in 2017. “These are human beings, and it’s been three years. That’s too long.”

Across Southern California, Chinese immigrants are watching the protests — the most extensive in China in a generation — with a mixture of sympathy and fear.

Last week, after an apartment fire killed at least 10 people in the city of Urumqi in far western China’s Xinjiang region, some blamed the deaths on pandemic practices that have sometimes resulted in doors being sealed to keep the virus contained, while trapping people in an emergency.

Candlelight vigils for the victims in cities including Beijing and Shanghai turned into protests, with groups chanting for the end of pandemic lockdowns. Some even demanded democracy, freedom of speech or the resignation of President Xi Jinping — highly unusual in an authoritarian state where police crack down at the slightest hint of dissent.

Since the pandemic began, Chinese people in Southern California have exchanged anguished texts and phone calls with relatives quarantined in apartments for months, often with limited access to food. The periodic lockdowns — a cornerstone of China’s “zero-COVID” policy — have continued even as the U.S. and other countries, including many in Asia, resume a relatively normal lifestyle.

Chinese security forces have put on a massive show of force to deter a recurrence of the protests that erupted in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities.

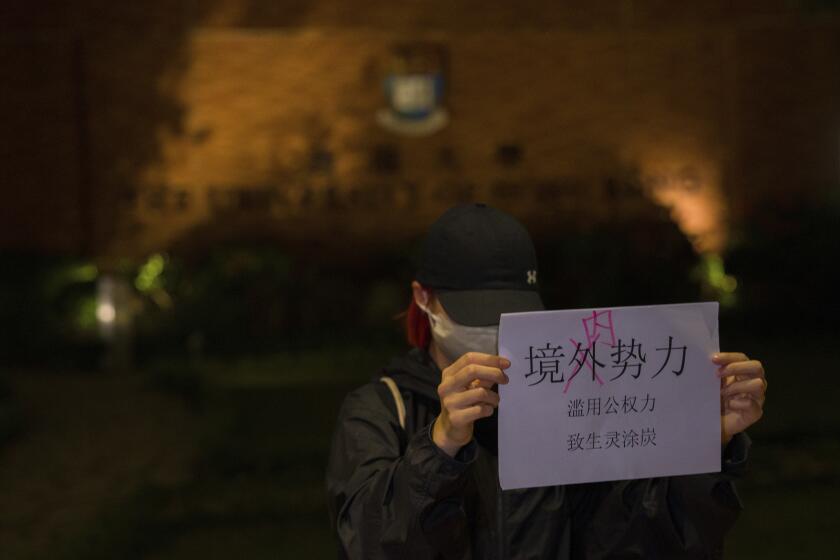

Blank sheets of white paper, adopted in Hong Kong several years ago as a statement against censorship, have become a symbol of resistance in China, with protesters holding them up en masse and the hashtag “White paper revolution” gaining popularity online.

On Wednesday in Beijing, police and paramilitary forces conducted random ID checks and searched people’s cellphones for photos, banned apps or other potential evidence that they had taken part in the demonstrations.

China’s ruling Communist Party has vowed to “resolutely crack down on infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces.”

In interviews this week, some Chinese immigrants expressed solidarity with the protesters. And as videos of police making arrests leak through China’s tightly controlled social media, they worried for the protesters’ safety. Few were optimistic that there would be lasting change.

“We don’t really know what’s going to happen,” said Jian Tian, a day trader and bitcoin miner in El Monte. “I’m worried the Chinese government will respond harshly and that could lead to beatings, arrests and more. Who knows?”

Tian was a small child in 1989 when pro-democracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square were brutally suppressed by the Chinese military.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Tian, 37, who came to the U.S. from Fujian province more than two decades ago.

Xuan Zhu is from the northwestern Chinese city of Lanzhou, where this month a father blamed his 3-year-old son’s death on COVID-19 restrictions that prevented him from rushing the boy to a hospital after a gas leak.

Zhu, a chemical engineering student, said he initially supported the Chinese government’s tough measures, thinking the virus could be contained. But the harshness of the implementation, along with the failure to import Western vaccines, has led Zhu, 24, to reconsider.

Over a bowl of his hometown’s signature beef noodles in Rowland Heights, Zhu said he could not predict what would happen to the protesters because there was no precedent for these types of demonstrations.

Shanghai native Karen Wang said she gets texts from old classmates about mass coronavirus testing and onerous requirements to provide proof of their daily activities to officials.

Wang, 26, who moved to Southern California shortly before the pandemic, expects it will be years before she can visit her family in China, because of long quarantines for travelers and fears of transmitting the virus to others. She expects China’s COVID-19 restrictions to tighten further before becoming looser.

Wang, who was shopping for groceries and enjoying taro milk tea in Garden Grove on Tuesday, said she supports the protesters.

If they don’t express their anger, she said, “who can speak” for them?

A restaurant owner in Alhambra, who is of Uyghur ethnicity, said he appreciates the support that many Chinese have shown for the Uyghurs killed in the apartment fire.

His father is one of as many as a million Uyghurs locked up in concentration camps as officials try to stamp out their Muslim religion and make them culturally Chinese. His mother is trapped in her home because of the COVID-19 lockdown in Urumqi, he said.

The restaurant owner, who would not give his full name because he feared for the safety of his family, said some in China had been unwilling to acknowledge the government’s human rights abuses against Uyghurs.

A vast system of Chinese surveillance, detention, cultural erasure and forced labor has devastated the Uighur people in Xinjiang, their homeland.

Now, he said, they are realizing that everyone, regardless of ethnicity, is “all the same thing in front of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“This is a breaking point,” he said. “They’re recognizing that the government is suppressing them as well.”

At USC on Tuesday night, hundreds attended a candlelight vigil for those suffering under China’s zero-COVID policy. Some at the vigil were draped in chains and holding blank sheets of paper.

Han Wang, a USC graduate student and native of Shanxi province who organized the vigil, said he feels “deep despair and anger” over the continual lockdowns in China. His parents have not been able to leave their home for at least 10 days, he said.

“The government is putting locks on the doors, putting shackles on the people,” said Wang, who is studying data analytics.

USC graduate student Qingyan Li said she has felt powerless watching clips of the protests and subsequent crackdowns in China. Her relatives in the southern city of Guangzhou seem either unaware of what was happening or too afraid to speak up, she said.

That led Li and a friend to the vigil at USC.

“I want the Chinese people to know that we are supporting them as well, because we’re Chinese,” said Li, 26. “I want them to know that we stand with them, and we want to send them courage, because they’re so brave.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.