Driving along the Columbia River near Celilo Park, the waterway appears wide and smooth, with only wind-whipped waves disturbing the surface.

But for millennia, the area was home to waterfalls where Native Americans fished for salmon and traded with tribes from as far away as British Columbia and the Great Plains. At Celilo Falls, the Yakama and other tribes used traditional methods to catch salmon until the late 1950s when the falls were inundated by The Dalles Dam.

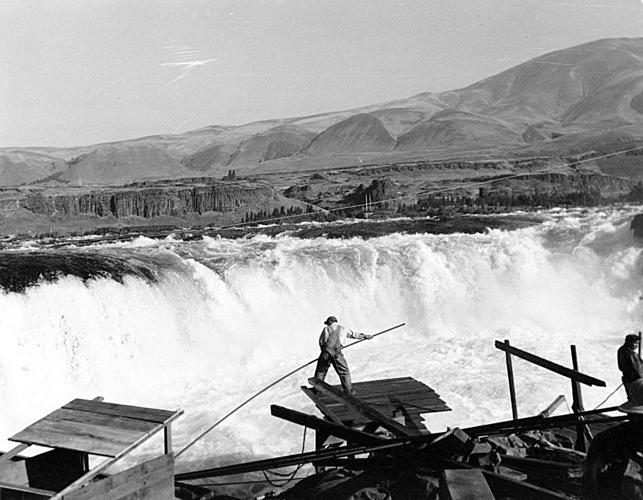

Celilo Falls was among many falls and rapids the Columbia passed through as it made its way to the Pacific. At Celilo, the water cascaded over 40-foot-tall basalt cliffs that formed a horseshoe nearly spanning the river.

Archaeological evidence shows that Native Americans were fishing for salmon there 11,000 years ago. The Upper Chinookan Wasco, who lived on the southern bank near The Dalles, and Sk’in-a-ma, who lived near what is today Wishram, lived by the falls year-round. But other tribes such as the Yakama would come there to fish for salmon, as well as trade with representatives of other tribes who came to the area.

They fished with dip nets or spears while standing on the cliffs, or from wooden scaffolds above the river, catching the salmon as they negotiated the cataracts around the falls. The nets were made by the women in the tribe, who kept the weaving technique a secret so they could regulate the men’s fishing.

The area was a thriving trading area when Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery passed through. They estimated the population around the falls at 7,400 to 10,400, with full-time and seasonal residents.

William Clark, in an April 1806 entry in his journal, noted that the area around the falls was the “great mart” of the region, with Native people trading horses, beads and buffalo robes for fish and other commodities.

It was also a spiritual place where people could give thanks for the land and honor the salmon that fed them.

When the Treaty of 1855 restricted the Yakama to their current reservation in the Lower Valley, they were granted the right to continue fishing at the falls, a right that was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905 when tribes that fished there challenged the use of fish wheels by non-native anglers.

But the falls — and the way of life — were doomed by efforts to make the Columbia more navigable, as well as convert the mighty river’s current into electricity.

Dams were built on the river that tamed the flow, but in turn inundated traditional lands. And Celilo Falls was no exception. When The Dalles Dam’s doors closed at 10 a.m. on March 10, 1957, the falls were flooded in less than five hours, forming what is today Celilo Lake.

Tearful tribal members sang traditional songs as the water rose over the cliffs, mourning the loss of a spiritual center. Others couldn’t bear to watch as the cliffs disappeared from view.

“The roar (of the falls) left us just like that,” Joe Jay Pinkham said in a 2007 interview with the Yakima Herald-Republic. Pinkham said he never fished on the Columbia after that.

An agreement between the federal government and the Warm Springs, Nez Perce, Umatilla and Yakama nations offered each enrolled member $3,700 — $32,743.21, when adjusted for inflation today — as payment for the loss of the falls. Some considered it an insult on top of the injury to their culture.

“That’s only a drop in the bucket compared to the electricity bills everyone pays,” Karen Jim Whitford said in a 2007 interview with the Herald-Republic.

The Native people who chose to stay there were relegated to a village with substandard housing, separated from the river by a highway and rail line.

Celilo Falls lives on in the Yakama’s culture. It is also commemorated on one of Toppenish’s murals and in a display in the main lobby of Legends Casino Hotel.

In 2007, the 50th anniversary of the dam’s construction, Celilo Village was renovated by the federal government, with a new longhouse and better homes, as well as improvements in the water system.

Dispelling rumors that the falls were blasted to pieces during the construction of the dam, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did a sonar map of the area in 2008, which showed that the falls were virtually intact.

Native Americans today continue to fish in the area, using gill nets.

“Celilo Falls may be gone, but it still echoes in our hearts,” Whitford said in 2007, tapping her chest. “It didn’t die here, it’s still here.”

• It Happened Here is a weekly history column by Yakima Herald-Republic reporter Donald W. Meyers.

(0) comments

Comments are now closed on this article.

Comments can only be made on article within the first 3 days of publication.