Water restrictions in Northern California have prompted protests from a Hmong community, who say the ordinance has led to discrimination and a rise in racial tension in the area.

The Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously last week to hold a third hearing about the ordinances, which were passed as emergency measures in May. Officials had claimed that the legislation, which prohibits water trucks — defined as vehicles used to carry about 100 gallons of water — from driving on designated roads and fines those who transport water without permits, were in part an effort to curb illegal cannabis farming. While growing cannabis is legal in the state, the county heavily limits the number of plants permitted on a property and forbids outdoor growing altogether.

But many Hmong residents, many of whom belong to the area's large farming population, said the policies disproportionately affect their community and have led to racial profiling by local authorities.

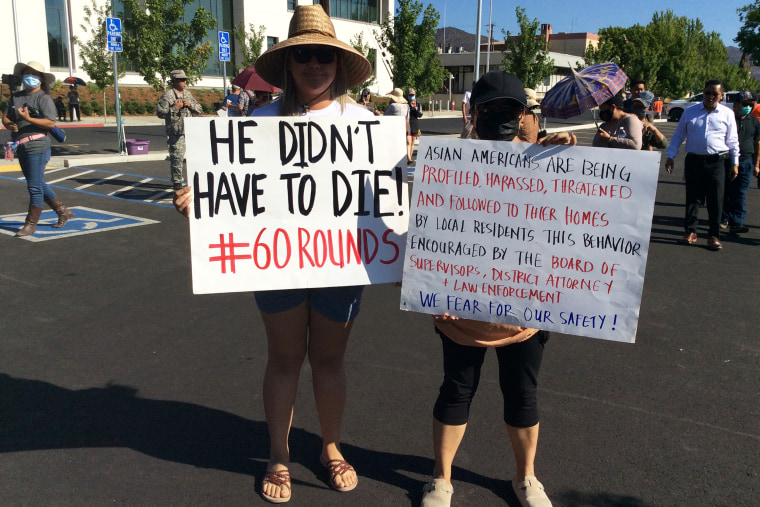

Activists say the policies have escalated tension among the Hmong community, other residents and officials in Siskiyou — pointing to an incident in June, when four officers from different agencies, including the sheriff's department, shot and killed Soobleej Kaub Hawj, a local farmer.

With the restrictions' possibly being voted into law, many activists say the legislation could deprive farmers and residents of their basic human rights.

"It's almost a visceral feeling, this tension between our communities," said Zurg Xiong, a Hmong organizer who undertook a three-week hunger strike to protest the county's handling of Hawj's death. "A lot of it was the local government and the sheriff's office actually stoking those tensions."

The sheriff's department did not reply to a request for comment.

Because of the drought in California, many families have had to go out and retrieve water for both farming and everyday uses like cooking, drinking and bathing.

Activists and organizers who have been speaking out against the ordinance for months say it has predominantly affected Hmong, as well as Chinese, farmers in the area. Many of the roads on which the board chose to ban water trucks are commonly used by the farmers or are close to their homes.

Activists also said that water permits are particularly difficult to get and that authorities have no way of differentiating illegal cannabis growers and other legitimate forms of agriculture, leading to unnecessary profiling and leaving many community members without a sufficient water supply.

Kao Ye Thao, director of policy and partnerships at Hmong Innovating Politics, a grassroots civic engagement organization based in California, said multiple Asian community members have reported having been harassed or stopped while driving.

"The ordinance itself was an emergency ordinance passed without really consulting with the community that it was actually going to be targeting. ... Now they're associating being Asian with being an illegal cannabis grower," Thao said.

The tension was palpable at the recent meeting, said Jaea Vang, a local organizer who was in attendance. As protesters hit back against the measures outside the courthouse, Vang said, a white man drove up to protesters with his water tank, splashing some of the water onto the street.

"His display to the Hmong community was that he can get water any time and anywhere but we can't," Vang said.

Communities in the area have been living under such stress for some time, with the rift reaching its height after Hawj's death. The farmer, who was 35, was shot and killed during an evacuation from the Lava Fire, which originated in the county, authorities said. The sheriff's department said Hawj, whose family was in a car behind him, pointed a semiautomatic handgun at the officers and entered an evacuation zone after he "ignored numerous directions by officers and attempted to drive around the roadblock."

Activists and community members have questioned the sheriff's account, particularly after a witness said more than 60 shots were fired at Hawj. Amid wildfires in the region, the sheriff's department has arrested more than 14 Hmong farmers, alleging that they evaded fire evacuations. But activists say the farmers were given little choice, as many were left to defend their land and crops from fire because first responders failed to protect them.

Sheriff Jeremiah LaRue previously told The Sacramento Bee that the growers were "hostile" to first responders.

"It prevented fire[fighters] from going in there, because the firefighters didn't feel very safe due to some of the comments that were made," he said. "So it's kind of a mess."

Following repeated protests and pressure from other Asian American officials, including Sacramento City Council member Mai Vang, California Attorney General Rob Bonta has agreed to look into Hawj's death and the allegations of discrimination against Asian Americans in the county. The killing is under investigation, led by the Siskiyou County District Attorney's Office, and all officers involved in the killing have been put on paid administrative leave. LaRue, who did not detail much of what happened, previously released a statement saying, Hawj's "death must be determined through a comprehensive investigation."

"Releasing information prematurely can have negative consequences that may compromise the investigation," LaRue wrote. "We continue to ask everyone to be patient with investigators and the process of determining the events surrounding Mr. Kaub's death. Information will be released as soon as possible."

LaRue told Jefferson Public Radio that race is not part of the discussion.

"It seems like it's about race. And it is not about race," he said. "It's just about conforming to the laws."

But Xiong points to Japanese American prison camps, California's history of burning Chinatowns and the California laundromat laws of the late 1800s, which restricted Chinese immigrants from operating laundromats based on immigration status.

"You have a really overt policies, like the Chinese Exclusion Act. And then you have the California laundromat laws," he said. "It didn't specifically state that they were targeting Chinese and Latino laundromats. ... When you consider the history of how our Asian American communities have been treated, this is simply just part of the system meant to exclude the outsider communities as perpetual foreigners."

The tension has created mistrust and heightened fears and anxiety across the Hmong community, particularly among the senior citizens who came to the U.S. as refugees, Xiong said. Many are still processing war trauma, and the circumstances have triggered some mental health issues.

Xiong said: "The elderly are very scared. They've been through total war. They know what it's like when an oppressor, when a supposed political government entity, comes and destroys their villages. ... This is still very fresh for them."

Little about the Hmong Americans' time in the area has been well-documented. Experts say there was a significant population spike in the county around 2015, fueled by the cannabis industry, farming, housing, property and economic opportunities. Although the terrain is considered difficult to farm, the community was able to adapt. Thao said most Hmong families in the U.S. have roots in Laos, where many were farmers before fleeing war and genocide.

"Hmong people were able to be in this community and farm and grow things out of what would be just very barren land. Because of the resilience of war and how we live, we've been able to create out of nothing," Thao said.

Now, as members of the Siskiyou County community, Thao said, the Hmong residents are simply "seeking truth and accountability."

"You think of how this is impacting the community. We have real people in a community suffering because they don't have water. They're being deprived of those basic necessities. We have a family that's mourning," she said.