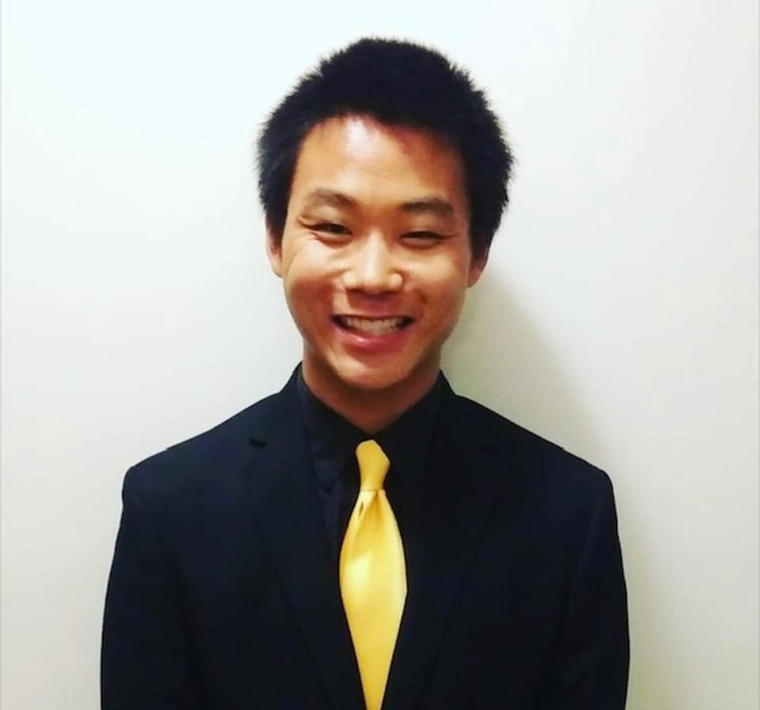

Fe and Gareth Hall miss hearing their son laugh as he relaxed on the couch, scrolling through TikTok videos.

It was a small affirmation of his presence that often punctuated the silences in their house.

“That’s what I miss. That’s what I miss so much — the noises he made,” Fe Hall said recently through tears. “I won’t hear those anymore.”

Christian Hall, 19, was killed by Pennsylvania State Police troopers on Dec. 30. As the anniversary of his death approaches, his parents are continuing to fight for an independent investigation into the shooting. They’re also reflecting on the last months before their son was killed, trying to understand what led him to the highway overpass where the fatal encounter unfolded.

There are no simple answers. This fall brought the painful release of police videos showing the final moments of Hall’s life, published by NBC News and Spotlight PA, which revealed that Hall had his hands in the air when he was shot. The State Police investigated the shooting and the Monroe County District Attorney’s Office ruled it justified this year, saying the troopers’ lives were in danger because Hall was holding a weapon, which authorities later determined was a realistic airsoft pellet gun.

Hall’s parents are suing the troopers who shot him, whose names haven’t been released, and they are calling on state leaders to open a new investigation. They also support a proposal to have independent prosecutors investigate use-of-force incidents involving the State Police, which was a recent recommendation by the State Law Enforcement Citizen Advisory Commission.

The State Police declined to comment on Hall’s case because of the pending litigation. They said in a statement: “Any loss of life is tragic. The trauma associated with a loss of life affects everyone involved.” The Monroe County District Attorney’s Office has defended its handling of Hall’s case and said an additional investigation is unnecessary.

As Hall’s parents wait for their court case to move forward, they’re holding a vigil across several cities this month to commemorate the anniversary of his death and to seek justice for him and other victims of police violence. Their thoughts are also turning to Hall’s early childhood, his difficult adolescence and the factors that led to his decline in mental health in the weeks before he died.

The Halls adopted their son from China in 2002 when he was a baby. As a child, he was diagnosed with reactive attachment disorder, which is marked by a difficulty developing healthy or secure attachments to caregivers and is more common among adopted kids. He often ran away from home and, after he accidentally started a fire in a nursing home, spent years in juvenile detention as a result. He was also diagnosed with depression.

In the fall of 2020, Hall was living at home and working at a grocery store. He had a girlfriend and was seeing a therapist who had experience working with patients who had reactive attachment disorder, his parents said. Therapy had been a consistent aspect of Hall’s life, both when he was in juvenile detention and after he was released, his parents said.

But as the pandemic wore on, he collided with difficult circumstances. Hall’s counselor left the practice in October, he went through a tumultuous breakup, and he became more withdrawn as lockdown and isolation continued, his parents said.

“He just came to me shaking and he said, ‘I need to talk to someone,’” Fe Hall said of a conversation she had with her son last December. “All I could do is say: ‘I am here. We can talk.’ But he said: ‘Mom, no. I need someone to talk to.’”

The Halls tried to find their son a counselor who had a background in working with patients with reactive attachment disorder, but that wasn’t easy in Stroudsburg, a town of 5,500. Hall’s parents widened their search to include professionals within 25 miles. But by the time they found a potential therapist and scheduled an appointment, it was for January. Hall had been without professional help for months.

The challenge of finding mental health care is a common one for Asian American adoptees, particularly those living outside urban centers, said Kimberly Langrehr, a Chicago-based psychologist and Asian American adoptee herself.

“They are living in a world that really knows little about adoption, is heavily misinformed about race and unfortunately also has a stunted understanding of mental health,” she said.

Hall’s parents hope his story brings awareness to gaps in culturally competent mental health resources for Asian American adoptees, as well as the importance of mental health training for law enforcement officers.

In 2015, just 3 percent of the psychologists in the U.S. were Asian, while the overwhelming majority were white, according to the American Psychological Association. There’s also a disparity between urban and rural areas, with metropolitan counties averaging about four times as many psychologists per 100,000 people as rural counties.

The Halls say such resources are key to getting people the help they need before they’re in crisis. And they wonder what could have gone differently if their son had such support.

Lack of understanding on mental health issues

On the afternoon Hall was killed, he called 911 from a highway overpass to report a “suicider.”

State Police troopers approached him and tried to persuade him to get down from the edge of the overpass. They spoke to him for about 90 minutes, urging him to put down the pellet gun he was carrying.

In the final 22 seconds before the shooting, Hall moved toward troopers with the gun in his hand at his side. After a trooper fired initial shots, which missed him, Hall raised his hands above his head, the gun in one hand. He had his hands above his head for 14 seconds, police videos show, before troopers fired the final shots that ended his life.

“He was the reason why we woke up and did the things that we did, and now he’s gone, and he was just taken,” Fe Hall said. “Like his life did not matter at all.”

Despite his 911 call, Hall’s parents don’t believe their son was suicidal. They believe he was distressed from a combination of a painful breakup, his depression and his reactive attachment disorder, as well as his being between counselors.

“It was not helpful to have a disruption — to have a disruption in his relationship with his girlfriend, a disruption with his counselor, the isolation. It was just so many things,” Fe Hall said.

In many cases, reactive attachment disorder, the symptoms of which include withdrawal, fear and irritability, is traced to a lack of care and touch babies get in their earliest days, Langrehr said. That’s why it can be found in some adoptees, particularly those who were raised in large orphanages who may not have gotten enough attention, she said. Some children with the disorder may have difficulty making eye contact and retract in response to being held, among other sensory issues, she said.

The Halls said their son began to show signs of the disorder in elementary school, when he had “explosive” outbursts and difficulty engaging in conversations. He also started running away from home.

The Halls said it’s unclear how their son felt about his adoption, but the family was open about the subject. Fe Hall said he had asked about his birth mother a few times, apologetically, fearful that he’d hurt her. Once, when he was about 10 years old, Hall was having a rough day on a trip to the Philippines when he raised the subject.

“Out of the blue he said, ‘I just want my mother,’” Fe Hall recalled. “I’ve never seen him say it that way again.”

Another difficult subject the family broached was race. Fe Hall is of Filipino descent and Gareth Hall is Black and Latino; their son was one of the few Asian Americans growing up in Stroudsburg, where Asian Americans make up just 2.5 percent of the population. Hall’s parents said they observed several instances of racism directed toward their son, including from peers.

Some adoptees struggle silently

Becky Belcore, a Korean adoptee who is an advisory board member of the Adoptees for Justice project, which advocates for international adoptees to receive U.S. citizenship, said adoptees’ feelings of grief may go undetected while still shaping their lives.

“Our very first experience as human beings is abandonment,” Belcore said. “That’s something that you carry with you.”

Many adoptees, particularly those with white family members, might also struggle — often alone or silently — with issues like feeling rejected by two cultures, racism and racial isolation, experts say.

The general adoptee population has higher rates of substance abuse, and they may act out in other ways, Langrehr said.

Belcore said adoption agencies or the government should assign caseworkers to help adoptees’ parents find the support they may need at different stages of their children’s lives.

Calling for mental health support alongside police

The Halls are working with the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance, a Pennsylvania-based nonprofit organization, to push for greater access to mental health care for Asian Americans, including those who are adopted.

The group wants the state to allocate more funding for mental health services, including money to train more counselors who have the language skills and cultural competence to treat the state’s diverse Asian American population. Mohan Seshadri, a co-executive director of the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance, said the need for such resources is increasing in rural parts of the state, not just in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

“There are those historic gaps when it comes to our communities but also just, quite frankly, historic disinvestment and lack of funding, lack of access, lack of resources … in a lot of these areas, specifically local municipalities,” Seshadri said.

The Halls also want mental health professionals to respond to 911 calls alongside law enforcement officers. Other cities, including Oakland, California; Denver; and San Francisco, have launched pilot projects with similar strategies, deploying teams that include mental health professionals to respond to some mental health crises rather than law enforcement officers. In New York City, which launched a pilot program in June, mental health teams had greater success persuading people to accept mental health care than police officers did alone, according to city data.

“Mental health workers should be there,” Gareth Hall said, adding that police “should work hand in hand with these mental health professionals to help de-escalate and let the mental health professionals take the lead on these kinds of calls.”

Mental health and crisis intervention training is a priority for the State Police, a spokesperson said. Training and continuing education, which are ongoing, include de-escalation strategies and partnering with local agencies, Cpl. Brent Miller, the director of the State Police communications office, said in a statement.

Fe Hall said she imagines her son on the bridge by himself, faced with several squad cars and uniformed troopers, guns drawn. Anyone, she believes, would react with confusion or fear.

“Police? They’re not caregivers,” she said.