Pollution and overuse threaten Florida's fragile freshwater springs

Declining flows, agricultural runoff, and sewage are pressuring the world’s largest network of freshwater springs.

Jason Gulley, a geology professor at the University of South Florida, often found himself inside caves below the surface of glaciers in Greenland or Nepal, exploring how melting ice affects rising seas.

When the pandemic shut down his travels, he shifted his attention to caves in his own backyard. Instead of rappelling a few hundred feet down vertical shafts in splintering ice, he swims deep inside underwater caverns in the porous limestone of the giant Floridan aquifer to document their failing health.

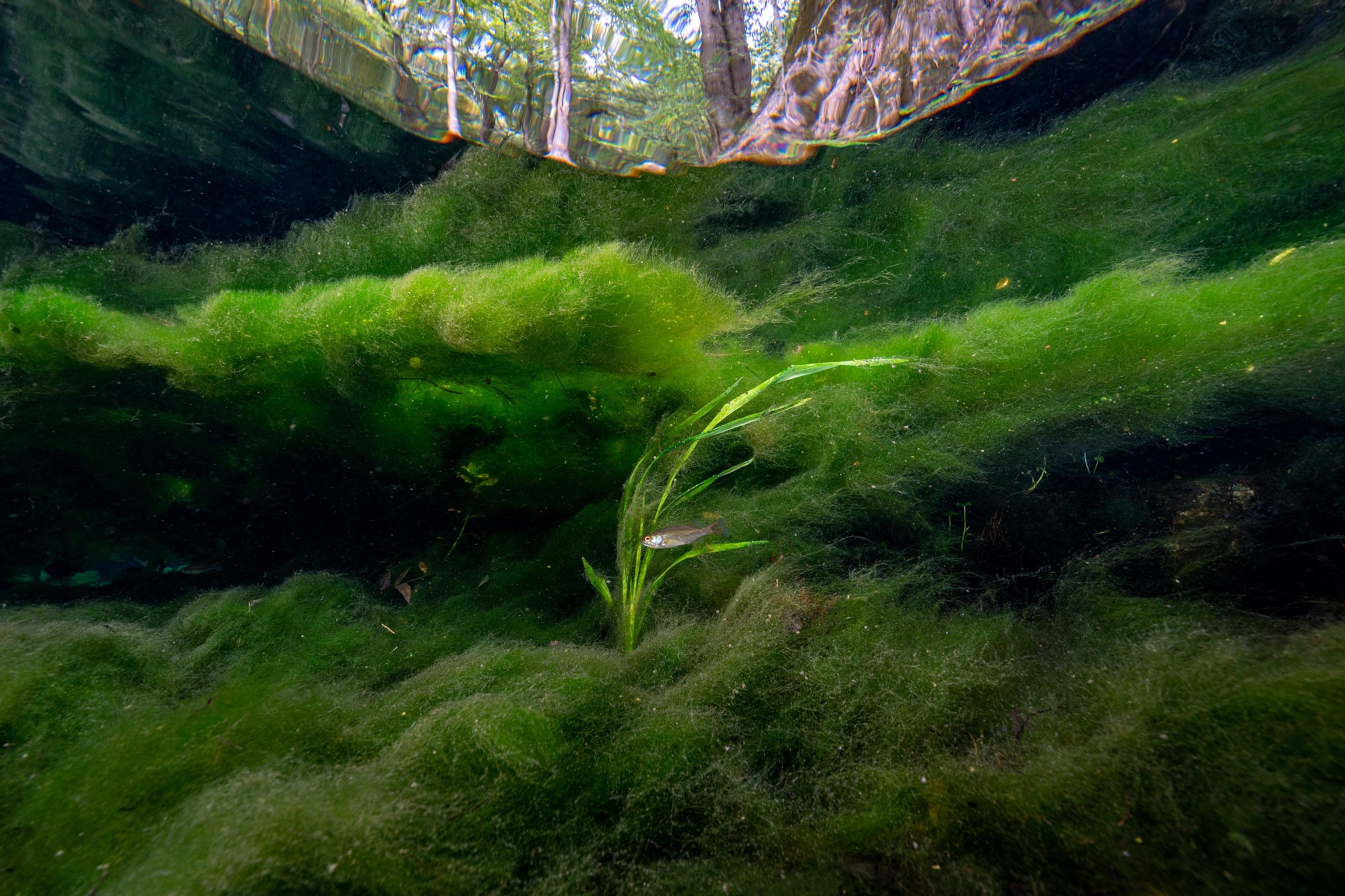

Springs are formed when outcrops of the limestone aquifer, which lies beneath the ground, rise above the surface and groundwater emerges, creating cool, clear pools and rivers brimming with aquatic plants and animals. The springs have been in trouble for decades, fouled by pollutants from agricultural runoff and sewage leakage and overdrawn to provide drinking water to 90 percent of Florida’s 22 million residents.

Gulley, who is also a National Geographic Explorer, calls their decline a “slow-motion environmental tragedy.”

Tom Frazer, a University of South Florida marine biology professor who served two years as Florida’s chief scientist, describes the situation another way. “The important thing to know about the Florida Springs is they are a direct link to the Floridan aquifer and the surface waters of our state,” he says. “I don’t think everyone realizes that the water we drink comes from that aquifer and the springs are a window into the health of our environment and an indicator of the health of our water.”

Increased pollution and reduced flow

More than 1,000 of these springs are spread across central and northern Florida, in the densest concentration of freshwater springs in the world. The best known are 33 "first magnitude springs," each of which produces almost 65 million gallons of freshwater daily.

Today, many of the previously clear blue waters have turned murky, and daily gushers have slowed to a trickle, thanks to over-pumping of the aquifer. Some springs have dried up completely. Sea level rise, which raises the level of the water table, increases the risk of saltwater intrusion into fresh groundwater and can eventually cause springs to stagnate.

In addition, nutrients in fertilizers have upended the springs’ natural balance, allowing algae to take over. The white sand floors of many springs are now covered over with algae blooms that grow in thick green mats and suffocate the eel grass—the primary food source for manatees that overwinter in the warm-water springs and the foundation of a healthy spring ecosystem.

One of Florida’s most popular tourist attractions

The springs have existed for millennia and were used as a water source by Indigenous people. Ponce de León gets the credit—whether deserved or not—for “discovering” them in 1513 on his failed quest to find the Fountain of Youth. By the late 1800s, the springs were so well known they had become a tourist attraction, marketed to northerners for their healing properties. Eventually, Hollywood came calling, drawn by the crystal clear water, so perfect for filming television shows like Sea Hunt and movies like the 1954 horror hit Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Today, hundreds of thousands of tourists visit the springs, where the average water temperature is 72 degrees Fahrenheit. The long-running mermaid shows at Weeki Wachee Springs, which date to 1947, became so beloved by crowds that even after the state of Florida acquired the springs and turned the area into a state park, the mermaid shows have continued, making Florida the only state in the nation with mermaids on the state payroll.

State efforts to protect the springs are ineffective

The state of Florida has taken steps to protect the springs. In 2016, the legislature chose 30 “outstanding” springs for additional protection and restoration. It created a series of basin management plans to improve water quality in the springs by reducing nitrogen pollution from agricultural runoff and sewage leakage. In summer 2020, Governor Ron DeSantis signed Florida’s Clean Waterways Act, which is aimed at correcting some of the worst water pollution in the state, including in the springs.

Yet algae still blooms and the pressure to pump more water from spring basins remains. Florida relies more heavily on groundwater during its many extended droughts, and its population continues to expand—the Sunshine State gains about 845 residents a day, adding the equivalent of a new city roughly the size of Orlando every year.

Mark Rains, Florida’s current chief scientist and director of the University of South Florida’s Water Institute, in Tampa, insists state officials are not operating “business as usual.”

“We’re not asleep at the wheel,” he says. “We are very much aware of the threats our springs face and what we need to be doing in order to restore them. But it’s complicated and in many cases, a long road back to full restoration for some of our springs. It’s a road we’ve decided we want to travel, but it’s going to be a road we have to travel for some time.”

He points to multiple projects under way to solve the problem, ranging from cleanups of waterways to construction of a desalinization plant south of Tampa that has been operating for a decade as an alternative source of freshwater.

Activists argue that the state’s efforts are too little, too late and are calling for more consequential action. Oscar Corral, an Emmy Award–winning filmmaker and former Miami Herald reporter, produced a two-part documentary about the springs that aired on PBS in April. He says the springs can be protected by designating the ones in northern Florida as a national park—a compelling idea, but one that seems unlikely to gain traction in Washington because of a number of hard-to-solve complications.

Creative alternative solutions

Chuck O’Neal, an activist in the global rights-of-nature movement, has come up with another big idea that needs no help from politicians, only voters. O’Neal and other environmental leaders are gathering signatures to place five constitutional amendments on the 2022 ballot to protect Florida’s water and wildlife. Four amendments would establish protections for wetlands, coasts, rivers, and springs; the most substantive of those would recognize legally enforceable rights of all waterways in Florida to “exist, flow, be free from pollution and maintain a healthy ecosystem.”

A fifth amendment would ban game farms, or “captive wildlife hunting facilities,” where deer, rams, and water buffalo can be killed. O’Neal has until February to collect the necessary 900,000 signatures required to qualify for the ballot, but says the group wants to have them by the end of November.

The amendments are patterned on a rights-of-nature amendment to Orange County’s charter that was approved by 89 percent of voters in the 2020 election.

“The Clean Waterways Act is a tinkering with a failed regulatory system,” O’Neal says. “We have witnessed in Florida the ongoing degradation of our waters with the false promise that regulations will in some ways make it better, but they don’t.”

Meanwhile, Gulley, the geologist, continues to record the condition of the springs. He took up photography in the 1990s, and shot photos to illustrate glacier research for scientists lacking access to the glaciers themselves. Now he hopes the power of photography will draw renewed attention to the plight of the Florida Springs.

His next excursion will involve using a thermal camera to record manatees that spend each winter in the balmy waters of Crystal River, on the Gulf Coast, protected from the colder waters in the Gulf of Mexico, where they cannot survive. Seagrasses have been successfully replanted there, attracting a year-round population of females and calves to the river.

On the Atlantic Coast, the collapse of the seagrass beds in the Indian River Lagoon triggered widespread starvation, adding to the list of dangers that threaten the beloved mammals. As of September 3, 937 manatees in Florida had died from multiple causes, a new annual record.

“I’m also photographing possible solutions,” Gulley says. “A successful seagrass restoration project in the Crystal River shows that this problem is solvable, if environmental protection legislation is coupled with restoration funding.”

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, has funded Explorer Jason Gulley’s work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park