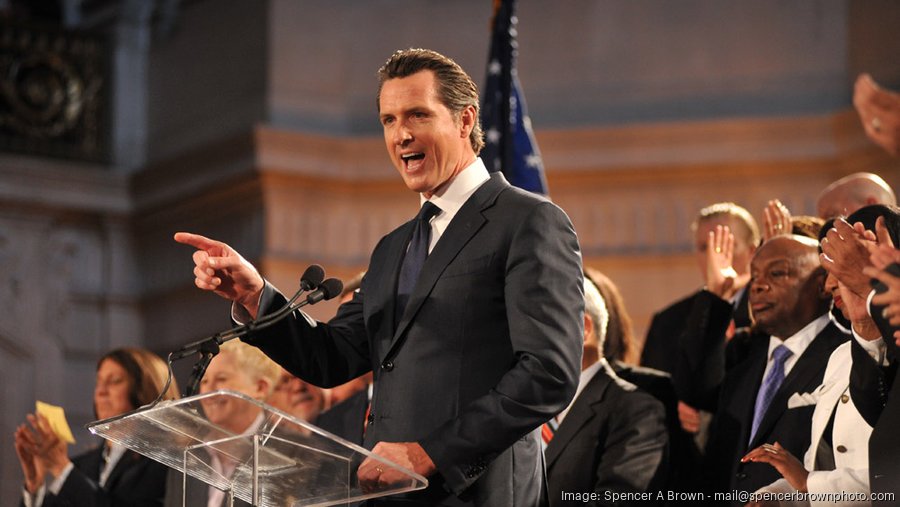

Few Californians took Gavin Newsom particularly seriously when he said during his 2018 run for governor that the state should plan to add 3.5 million homes over the next seven years. After all, California has never in its history reached that pace of construction for a single year — let alone done it seven years on the trot.

It turns out he might have meant it.

Firing a shot across the bows of California’s cities, counties and regions last week, his administration shocked Southern Californians by telling them they will be required to make plans for 1.3 million new homes in their midst over roughly the next decade. That was triple the number that local officials who control the Southern California Association of Governments had said they would support.

Of course, what the governor does to follow up and enforce his edict will entirely determine its success or failure. But the significance of calling out local officials representing nearly half the population of the state for insufficient attention to housing shouldn’t be underestimated.

The Bay Area is on a different timetable than state's south for receiving its state-assigned housing targets. So the parlous task facing the Association of Bay Area Governments — turning the state's eventual number into individual quotas for our 101 cities and nine counties — has yet to begin.

But a few things seem clear from what just happened in Southern California.

First, every city, county and neighborhood in our region is going to be required to do more — a lot more. Like almost everything associated with housing policy, the process for setting quotas is a complicated exercise. But comparing populations, very rough math suggests state officials may be looking for nearly 500,000 new housing units in our region. That’s quite a difference from the 187,000 homes the Bay Area was assigned for 2015-23 — a target it is in the process of undershooting by a large margin.

Second, the delaying, denying and downsizing of housing proposals that has become almost epidemic in the Bay Area needs to be confronted with all the force the state can muster. Nobody gets to opt out of collective action.

Third, the blowback and noncompliance that can be expected from certain cities illustrates there’s still a pressing need for state legislation that can clear the way for new housing in our urban and suburban cores.

Our housing crisis took decades to build to its current proportions. Addressing it will probably take just as long. But embracing the scale of the challenge is a good place to start.