Older people will have to make sacrifices in the fight against climate change or today’s children will face a future of fighting wars for water and food, the EU’s deputy chief has warned.

Frans Timmermans, vice-president of the EU commission, said that if social policy and climate policy are not combined, to share fairly the costs and benefits of creating a low-carbon economy, the world will face a backlash from people who fear losing jobs or income, stoked by populist politicians and fossil fuel interests.

He said: “It’s not just an urgent matter – it’s a difficult matter. We have to transform our economy. There are huge benefits, but it’s a huge challenge. The biggest threat is the social one. If we don’t fix this, our children will be waging wars over water and food. There is no doubt in my mind.”

Tackling climate change will be many times cheaper than the disruption that global heating will cause, as well as bringing benefits to health, and the costs have fallen dramatically in recent years. However, the shift away from fossil fuels will mean the end of some traditional jobs such as coalmining, and the costs of change will fall unequally on different sectors of society unless politicians step in.

“Where I see a huge risk is that you get an alliance between those who don’t want change because they see their interest affected, whether it’s in fossil fuels or in traditional economic circles,” Timmermans told the Guardian in an interview. “Those interests combine with the fear of negative social consequences. Then you could get a counter-momentum where people say, ‘Hang on, not too fast, people cannot stomach this.’”

He added: “Those of us who understand we need to move fast should make the social issue the pivotal issue in all of this. I really call upon all of those in the climate movement to join me in focusing on the social issue more than they’ve done in the past. Because this could become the biggest stumbling block.”

He warned that sacrifices would be needed from the older generation to ensure that young people can live in a safe climate. Today’s older people were the beneficiaries of a previous generation’s sacrifice, and were now being called on to make changes themselves, he said.

“Sometimes I wonder whether we are aware of the transformation we’re heading to, and how profound it is. It’s an effort comparable to restructuring after a violent conflict. I used to talk to my grandparents and my parents about how they saw this, after the war. They said, ‘Well, we sacrificed a lot because we knew our children would be better off.’ And this feeling is not there yet in our society.”

Changing people’s lives today would be difficult, but the benefits would be felt by today’s children, he added. “This for politics is a huge, huge challenge. We need to recapture that feeling of a purpose – doing something not for yourself, but for others, which I think has always led to society being at its best.”

Any sacrifice would be mild for most, such as the inconvenience of having a house renovated to low-carbon standards, or switching to electric transport, and eating less meat. But for some it could involve a change of job or living patterns.

“We’re not asking people to go back to 1930s situations, we’re not asking people to live in caves and munch grass. It’s taking perhaps one or two steps back to be able to jump much further in to the future.”

Timmermans’ warnings reflect a growing concern among climate experts that politicians have failed to show people the benefits of a low-carbon society, which include cleaner air and water, more livable cities, and higher levels of health and wellbeing, as well as defusing the climate crisis. Politicians, including Donald Trump and Republicans in the US, have presented tackling climate breakdown as a cost, and many people are fearful for their jobs.

Timmermans acknowledged that some people in traditional industries would have to change, and said the main role for politicians was to make this easier. Reskilling people in industries such as fossil fuel and power generation would be key.

He pointed to Poland, which is highly dependent on coal. “They have a very high level of engineering, of education – there’s a huge potential there [in a low-carbon economy] for a country like Poland. And there simply isn’t any future in coal. The longer you protract [the change], the more painful and the more costly it will be.”

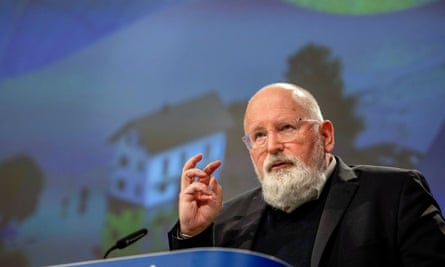

Timmermans has a pivotal role this year, within the EU and globally, as he leads the bloc’s green deal, intended to transform the European economy to a low-carbon footing, and leads the bloc’s climate efforts at Cop26, vital UN climate talks to be hosted by the UK in Glasgow this November.

On Thursday, he travelled to London for his first official visit outside Brussels since the pandemic lockdowns began, with a four-hour meeting in Downing Street with Alok Sharma, the UK’s Cop26 president and host of the talks. He is in weekly contact with John Kerry, climate envoy to US president Joe Biden, and with China’s top climate official, Xie Zhenhua.

The EU has put in law its own climate target, of cutting emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. This is one of the most stretching climate targets yet put forward, alongside those of the UK and the US, though campaigners have said the bloc could do better and have called for a 60% target.

Timmermans said no further improvement of the emissions target was possible, but said he was asking EU member states to come forward with more money for climate finance: assistance from rich to poor countries to help them cut emissions and cope with the impacts of climate breakdown.

“Our approach is ambitious; I think we’ve set the stage. I hope others will follow that example. I see what the UK is doing – that’s even slightly more ambitious than what we’re doing. But then all the others still have a lot of catching up to do. I think the onus here is not on the EU, nor on the UK.”