In the heart of the Pacific Northwest, the fate of the Lower Snake River and its dams is tied to individuals such as Miles Johnson, a salmon advocate, and Michelle Hennings, who assists wheat farmers relying on the dams for agricultural transportation.

This long-standing narrative of renewable energy's impact is transitioning from a simmer to a boiling point, with talks intensifying about breaching, or removing, four dams on the Lower Snake River. The future of low-cost hydropower, irrigation, and transportation advantages on the Lower Snake River, as well as the survival of endangered salmon, hangs in the balance.

For Johnson, who is the legal director for Columbia Riverkeeper, it's not enough to bring the Snake River salmon back from the brink of extinction, but rather see the population flourish to healthy and harvestable numbers. His dream is rooted in abundance.

He said for many people, salmon provides paychecks, meals, and a cultural connection to past traditions, but in the Columbia River and its tributaries, salmon are dying.

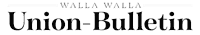

Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite dams are in Southeast Washington on the largest tributary along the Columbia River. At 465 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean, Lewiston, Idaho, is the farthest inland port on the West Coast. Lower Monumental and Ice Harbor dams are located in Walla Walla County where the Snake River is the county line.

Impact on salmon

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, sixteen stocks of fish historically spawned above Bonneville Dam. Of those, four are now extinct, seven are endangered species, and of the remaining five stocks, only one approaches its historical numbers.

In a subcommittee on Energy, Climate, & Grid Security hearing on Tuesday, Jan. 30, Jeremy Takala, chair of the Yakama Tribal Council’s Fish and Wildlife Committee, submitted witness testimony on behalf of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation.

In the testimony, Takala spoke about the importance of salmon and the health of the waters in the Columbia River Basin to the Yakama Nation.

The Yakama Nation is a sovereign Native Nation comprised of the confederated peoples of fourteen historic tribes and bands from the Columbia River Basin. In 1855, the U.S. Treaty with the Yakamas of June 9, 1855 reserved Treaty fishing rights to the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce Tribes, including a reserved right to catch 50% of the harvestable adult salmon returning to the Columbia River each year.

“Since time immemorial, the strength of the Yakama Nation and its People have come from Nch’í Wána — the Columbia River and its tributaries — and from the fish, game, roots and berries nourished by their waters,” Takala said. “Today, the majority of tribal fishermen on the Columbia River are Yakama Members. And Yakama Nation Fisheries operates one of the largest and most sophisticated fisheries management and restoration programs in the Nation. We are Salmon People; but we are also farmers, ranchers, loggers and entrepreneurs.”

"We must restore Columbia Basin fisheries to healthy and abundant levels. The economic and ecological health of our region requires it and my people's tribal treaty rights demand it. As the U.S. Supreme Court recently affirmed, treaty fishing rights include the right to actually catch fish, not just to dip our nets into empty waters without salmon."

Water flows through the Snake River’s Lower Granite Dam spillway.

The agreement

Decades of litigation and controversy surrounding renewable energy through the dams have led to an agreement between a number of parties. Columbia Riverkeeper, in collaboration with fishing, environmental, and renewable energy groups, has reached an agreement with the Biden Administration, Oregon, Washington, and the Nez Perce, Yakama, Warm Springs, and Umatilla tribes.

The agreement recognizes that the path to restoring abundant salmon populations in the Columbia River Basin — a collection of tributaries spanning 258,000 square miles — involves multiple steps and considerations.

The Lower Snake River dams are Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite.

It provides a roadmap, encompassing new funding for fish and wildlife research, tribe-sponsored clean energy projects, increased flexibility within the federal hydro system to benefit certain fish species while ensuring grid reliability, and studies on dam services. These studies explore how transportation, irrigation, and recreation services provided by the four dams could be replaced.

The agreement isn't cheap though with the U.S. government planning to invest $300 million over the next decade to help recover salmon populations in the river basin.

While the agreement does not call for the removal of the dams, some conservationists, such as Johnson, say the support and call to action is a step in that direction.

"I think the goal of continuing to maintain and keep the basin a beautiful and thriving place is shared by most people in the Northwest," Johnson said. "Even if we don't always agree on the exact path forward."

As a managing attorney, Johnson said he directs the work on the Lower Snake River Dam removal and works to address water pollution in both the Columbia and Snake rivers.

"At Columbia Riverkeeper, our mission is to protect the water quality of the Columbia and its tributaries from its headwater to the Pacific," he said. "We do this work so that everyone in the Columbia River Basin can enjoy the benefits of the place we live."

He said clean water, robust fisheries and healthy fish to eat are important aspects in supporting the economic landscape and way of life for those who use the basin. That is why Johnson has been sounding the alarm for dwindling salmon populations, particularly in the Lower Snake River Tributary.

“In 2023, 80% of endangered Snake River sockeye salmon died while migrating through eight dams on the Columbia and Lower Snake rivers,” he said. "The idea of abundance is not possible with those four dams in place."

Because of the statistics, Columbia Riverkeeper sent a legal notice of intent to file a new Endangered Species Act case against the Army Corps of Engineers to require action to keep the Lower Snake River cool enough for salmon. Along with the notice of intent, the organization included thousands of comments from the public on the matter.

Johnson said there are several reasons the four dams are preventing the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations. Besides the toll of going over and through the dams, he said warming waters from slower flow is to blame.

"The dams and reservoirs have really changed all aspects of how salmon and steelhead used to migrate," he said. "These rivers used to be fast flowing, cold and turbid. Now, the water is slowed down, it's warmer and it's clearer, allowing for predators to easily pick out juvenile fish. It also takes so much longer for these fish to migrate through this stretch of river."

Because the dams are federally owned by the Army Corps of Engineers, breaching them would take an act of Congress, which is no small feat.

Impact on utilities

Paul Ocker, Walla Walla District's Chief of Operations for the Army Corps of Engineers, said the construction of the Lower Granite Lock and Dam was the final piece of the puzzle in creating a navigable Snake River. Before the channel was established, travel on the Snake and Columbia rivers depended on seasonal flows, which were dangerous and unpredictable.

Besides making the river safe for transporting goods, the dams are also a producer of hydroelectric power.

"In any given year, like in 2021 for example, we made enough power from the four Snake River Dams to power one-third of the state of Washington's homes," Ocker said. "Some people say that's not a lot of power coming out of those dams, but it actually is quite a bit."

An adult spring chinook at the Lower Granite Dam on the Lower Snake River in 2019.

Ocker said even 20 years before, it was estimated that the dams were generating enough power for up to two-thirds of Washington's homes.

Heather Stebbings, interim executive director of Northwest RiverPartners, said removal of the dams could have a significant impact on utility bills. The main mission of Northwest RiverPartners is to promote hydropower as the primary driver of a clean energy future. It is a member-driven organization that serves not-for-profit, community-owned electric utilities in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Nevada and Wyoming.

"From the RiverPartners perspective, the loss of dams means the loss of that baseload to provide electricity to the region in a renewable manner," Stebbings said. "The dams provide low-cost, green-energy and if we remove the dams, we will ultimately increase cost for communities across the Northwest. A lot of those communities are underserved populations."

She said in the research that Northwest RiverPartners has conducted, people could see a 5% to 50% increase in utility bills.

"There are real impacts to these conversations," she said. "We believe this issue really needs to be looked at in a holistic manner that balances the environment, recognizes the historic and cultural value of the salmon and also takes into consideration that whole communities would feel the impacts of the removal of the dams."

One of the main impacts of dams is that they block rivers, interrupting fish migrations. Lower Granite is the first dam that juvenile salmon pass on their way to the ocean and the last dam for returning adults.

Ocker said the Army Corps of Engineers has a number of methods to help salmon populations pass the dams. The Corps uses a fleet of special barges to move juvenile salmon and steelhead at Lower Granite, Little Goose and Lower Monumental dams. The fish are carried downriver to be released below Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River. From 2013 to 2022, the organization reported that about 6.4 million juvenile fish were transported each year.

In addition to many changes in operations, structures have been added to the dams to improve fish passage.

"Typically, we have high survival of fish that we do transport," he said. "It's not a natural passage route, therefore a lot of people are not very happy with that as a methodology. Other juvenile fish passage routes at the dams now provide much higher survival than we had 20 years ago."

Fish ladders for adult fish returning from the Pacific Ocean to spawn were installed at the dams when they were first constructed. Improvements have also been made to the ladders as time has passed. Ocker said this is a successful passage route. Additionally, both Lower Granite and Little Goose dams have fish ladder cooling systems to help keep water temperatures in the ladders below 68 degrees.

If the dams are removed, Ocker said one major concern would not be water, but rather what has built up behind the dams in the 60 years they have been in place.

"The biggest challenge that we might see is that if we were to remove a dam, the amount of sediment that has accumulated behind, for example, Lower Granite Dam, is thought to be quite significant," he said. "It would be difficult for all species of fish if all of that sediment were to come down at the same time, essentially suffocating them."

Employees of the Corps of Engineers would take a hit as more than 300 personnel are employed across the four dams. Ocker said if the dams come out, those jobs would disappear.

"Other things to consider are all of the contractors who are hired to clean, construct improvements and assist in maintenance at the dams. A lot of our employees and contractors live in small towns like Washtucna, Dayton and Starbuck," he said. "Those jobs would be lost for those communities."

Impact on wheat exports

Nat Webb grew up farming in Heppner, Oregon, a town nestled between fields of wheat and other crops. His family homesteaded in the region in the mid 1800s, raising sheep and cattle. He attended Oregon State University, studying business. From there he worked for Shell Oil for a few years and decided he wanted a change. In 1973, Webb returned to the Walla Walla area to farm with his father.

Wheat pours into a 90,000-bushel barge moored on the Snake River alongside Tri-Cities Grain in Pasco.

Webb said in his 50 years of farming, he served as president of the Walla Walla Association of Wheat Growers, National Legislative Chair for Washington Association of Wheat Growers, member and chair of the Washington Grain Commission and board member of U.S. Wheat Associates.

“I have some background in the wheat business beyond just raising it and delivering it to the local co-op," he said. “I was interested in wheat farming and all the aspects of the market. I was able to meet a lot of people, and I learned a lot. There is so much more to farming than raising your wheat and then delivering it to the local elevator.”

He said the Columbia River basin and all its tributaries are a cornerstone of the regional agricultural economy.

“It’s concerning to think about what kind of impact this could have on the entire Pacific Northwest,” Webb said. “Some of the wheat that is produced in the upper Midwest is also barged on the Lower Snake River, too.”

The tributary also barges upwards of $21 million in goods on the Columbia-Snake River System that runs to Portland and Vancouver. Webb recalled a moment when he was serving on the U.S. Wheat Board when there was a proposal to shut down one of the dams near John Day for an extended period.

“The board had members from just about every state, and I remember that most of them were not very concerned about the extended shutdown, until they realized just how much wheat moved on that river,” he said. “All of a sudden, it was more important than they thought.”

The removal of the four dams on the Lower Snake River could have severe repercussions on the transportation of agricultural goods in the region, according to Chris Peha, CEO of Northwest Grain Growers, or NWGG.

Most of the grain from Walla Walla and Columbia counties, currently transported via barge on the Snake River to the Columbia River District export elevators, would face significant challenges.

"A very high percentage of the grain we handle would have to find a new mode of transportation to the Columbia River District export elevators where our grain is shipped to be loaded on an export vessel," Peha said.

He said trucking and rail options, the likely alternatives, come with many impacts.

"Trucks and rail options have much higher transportation costs, detrimental environmental impacts, and are much less safe than moving barges," Peha said.

According to the National Waterways Foundation, barges are the most fuel-efficient modes of transportation. Rail cars are 30% less efficient, and trucks are 78% less efficient.

Addressing the potential harm, Peha highlighted the need for infrastructure improvements to accommodate higher volumes of trucks and rail cars. He said because the existing road and rail systems were built more than 100 years ago, they would require substantial upgrades to handle the increased transportation demands.

Regarding market competitiveness, Peha said barge rates on the Snake River are significantly lower than truck and rail rates.

Ice Harbor Dam was built from 1956 to 1962 and began producing power in 1976. The dam was dedicated by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson on May 9, 1962.

Ice Harbor Lock and Dam is upstream of the Tri-Cities on the Lower Snake River.

"Our growers and our communities would all suffer the higher costs of transportation," he said. “Barging is the most economical, safest, and fastest way to reach our end users. It is not only going to affect the way we ship grain, but it will also have to change the way our customers do business.”

Rates for barging wheat on the Snake River are roughly $.45 to $.50 per bushel while single car rail rates out of Walla Walla and Columbia counties are about $1 per bushel. Truck rates to the same destination are even higher at $1.10 to $1.20 per bushel.

Peha stressed the need for increased investment in infrastructure to support alternative transportation routes and storage facilities if the dams are breached. He said most of NWGG company investments have been made at the river terminals the organization owns.

“Those elevators would become obsolete if the dams were removed,” Peha said. “We would need to invest tens of millions of dollars in our country elevators located on rail lines to build additional capacity and improve load out speeds and increase rail sidings.”

Michelle Hennings, executive director of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers, echoed Peha's concerns and said removing the dams would affect more than just the region. Washington Association of Wheat Growers is a nonprofit, grass-roots membership organization that represents wheat farmers across the state. The organization has about 1,800 members.

She said the organization's mission is to represent and protect the interests of wheat farmers and that mission is directly related to the concerns about removing the lower Snake River dams.

“Barging for wheat farmers is vital for the product that is transported,” Hennings said. “Approximately, we export 90% of our wheat overseas. We feed the world.”

Some of the top countries that Washington wheat is exported to are the Philippines, Japan and South Korea.

“This issue would not just be regional, but also national because we have other states that send their wheat through our system,” she said. “Sixty percent of all U.S. wheat exports move through the Columbia and Snake River systems and 10% of that wheat passes through the four locks and dams on the lower Snake River.”

Hennings said any disruptions to exports could potentially hurt existing relationships with trade partners.

“Breaching the dams could significantly hurt our ability to consistently supply a cost-competitive, high-value food product compared to our competitors,” she said.

Hennings said there are farmers across the state who support conservation efforts to restore salmon populations, but they think there are alternatives to removing the four dams.

"People, salmon and dams can coexist," she said. "We have the research and technology that can get us where we need to be."

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Posting comments is now limited to subscribers only. Become one today or log in using the link below. For additional information on commenting click here.

Log in

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.