The best job Greg Steen ever had was as a DJ at KRIZ 1420AM in Seattle. It was late 1989, and the then-24-year-old had just finished a crash course in radio production at the Ron Bailie School of Broadcasting, at the time tucked into a handful of small control rooms on Denny Way.

He adopted the DJ name “Greg Miles,” interviewed with KRIZ, and, as a trial run, recorded an advertisement for The Seattle Medium, the weekly newspaper that owned KRIZ at the time. Both KRIZ and The Seattle Medium were—and remain—among the very few African American-owned media outlets in the Pacific Northwest. Steen says his boss, Frank P. Barrow, then and now a legend on the Seattle radio scene, played the tape back to the Medium’s owners and told them, “When I grow up, I wanna have a voice like this.”

Steen got the job, and was quickly moved to the prime-time slot, 7 p.m. to midnight. He loved it. He was recognized by national magazines; he recorded tracks with Sir Mix-A-Lot, who had been a few grades ahead of him at Roosevelt High School; and in 1990 he scored an in-person interview with LL Cool J—the man he calls “my idol in rap.” Steen says that when he shyly informed LL Cool J that he’d had some experience making music himself, the artist told him something he’s never forgotten: “Man, whatever you do, don’t give up.”

Today, Steen’s voice is still smooth and bell-clear, his pacing still nimble as though he’s live on air. He drops into the old cadence with ease: “It’s 7:05, 55 minutes from the hour of 8 o’ clock, 1420 KRIZ, 1560 KZIZ, it’s your man Greg Miles on a super Saturday-night edition of KRIZ Lovelines.”

Then his voice changes, dips low. He tries to articulate a crippling love affair with crack cocaine and booze and a reckless attempt to join the Marine Corps before being sent home with a dirty drug test. “I went on a hell of a binge,” he says, “and I just got a bad idea one day. I said, ‘You know, I’m tired of this radio, I’m done with this job.’ It was one of the worst mistakes of my life.”

Steen, now a stocky, bald 51-year-old with a goatee, speaks across a staticky phone line from the Clallam Bay Corrections Center, where he, like nearly 1,400 others in the state of Washington, is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. If he ever does get out, he says, he’s planning to be on the radio again.

The Greg Steen who would take the mic then would be very different from the one who walked into the KRIZ offices decades ago—or, Steen says, from the one who robbed five banks during a crime spree almost nine years ago. Since the beginning of his life sentence in 2009, he’s done therapy, trained to become a yoga teacher, and had what he describes as a “kundalini awakening.” He meditates, mentors other inmates, works as a teacher’s assistant for classes taught at Clallam Bay, and is taking two courses himself. He’s even drafted a memoir. “I think that if I just continue, and continue, and continue,” he says, “I’ll be somebody I can’t really see right now. I’ll just be a new guy.”

These are the kinds of accomplishments that might impress a parole board, the kind a prisoner might trot out in a plea for early release. Certainly that is what Steen would like to do. But it’s unlikely he’ll be able to, no matter what kind of guy he becomes.

Washington state does not, technically speaking, have parole. It is among 14 states in the union that do not offer—or severely limit—the conditional release of a prisoner before his or her full sentence is complete. Those who don’t have cause to know that—for either professional or personal reasons—often don’t know it, says Layne Pavey, founder of I Did the Time, a Spokane-based advocacy organization that focuses on prisoner re-entry and supports sentencing reform in Washington. “It’s terrible,” she says. “People don’t know,” and sometimes, “the people who do know justify it and want it to be the way it is.”

This hasn’t always been the case. Throughout most of the 20th century, Washington did have parole. Most sentences were “indeterminate,” meaning that a judge typically handed down a maximum sentence, and an offender was eligible for review and release after a certain portion of that sentence had been served. But in 1975, state lawmakers and criminal-justice experts began to question that system. Christopher T. Bayley, the King County Prosecuting Attorney at the time, advocated for “determinate” sentences that delivered specific punishment based on the seriousness of the crime. He saw a defendant’s attitude, his or her need for treatment, or the potential risk of future offenses as irrelevant. A bipartisan House committee took up the charge, and in 1981, following the Senate’s shift from a Democratic to a Republican majority, the legislature passed the Sentencing Reform Act, which established determinate sentencing as the preferred approach. It also carved a path for the elimination of the state’s parole board, which critics contended made release decisions with too much discretion and bias. By 1984, parole had been abolished.

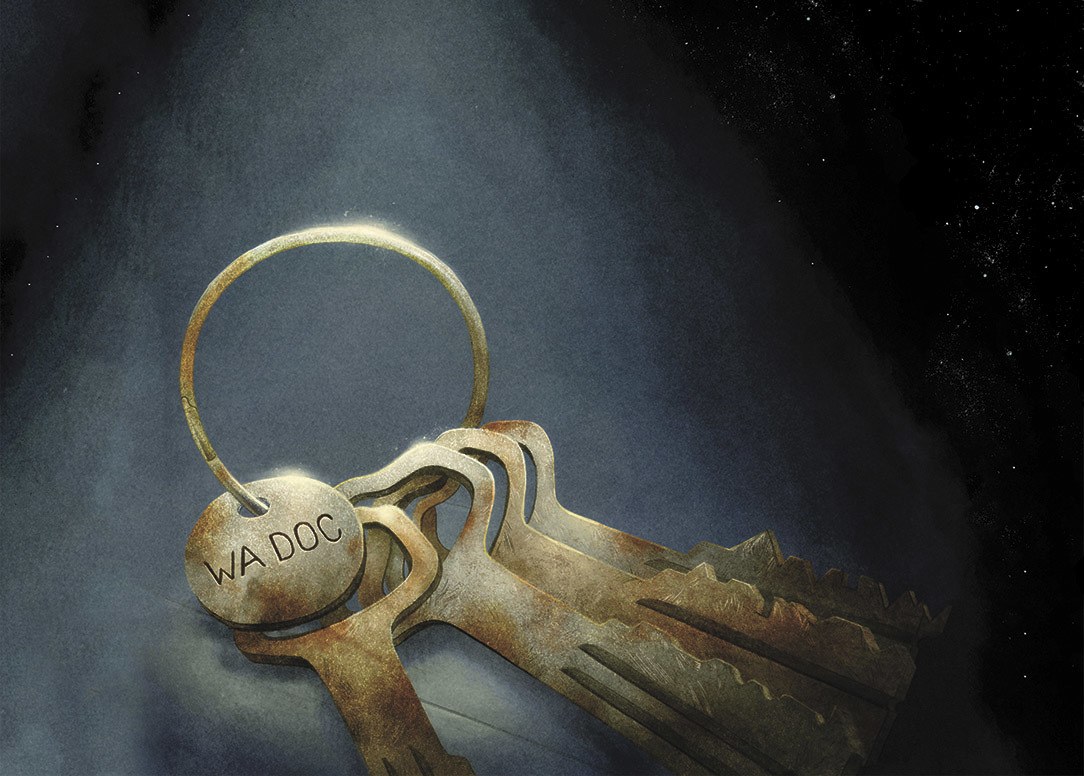

In its place now is the Indeterminate Sentences Review Board (ISRB), a panel run by the Department of Corrections that reviews three types of cases: certain sex offenses committed on or after September 1, 2001; cases involving juveniles sentenced as adults; and any crimes committed before 1984. None of these apply to Steen, or to many of the prisoners currently serving some version of a life sentence in Washington state prisons. For them, the only chance of release is through the Clemency & Pardons Board, housed in the governor’s office since 1981. It holds between two and three dozen hearings per year—about a quarter of the petitions it receives—with a fraction of those receiving clemency. Washington’s parole board held 5,000 hearings in 1980 alone.

Prior to 1984, a life sentence in Washington often meant 20 years, with up to a third of that time off for good behavior in prison. Now, “Life means life in our state,” says King County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg. It grew out of a “ ‘truth in sentencing’ mantra… . People said, ‘They got a life sentence, that’s what they have to do.’ ”

Washington’s shift away from parole was in line with a national movement to adopt “tough on crime” policies that swept from the Reagan White House to state legislatures to the streets. Over the next two decades, these policies, in Washington and elsewhere, quashed the idea of rehabilitation in favor of longer sentences, mandatory minimums, life without parole for persistent offenders, and extra time for firearms.

As a result, the number of people in state and federal prisons across the country exploded. In Washington state, the prison population has more than doubled since 1984; across the country, it has grown from about 500,000 in 1984 to 1.5 million today, with another 700,000 in local jails and detention centers—by far the highest incarceration rate in the world.

The number of people serving life sentences, in particular, has quadrupled in the past 30 years, according to a report released in January by the Washington, D.C.-based Sentencing Project—an even faster rate of growth than the overall prison population. About 160,000 people are now serving life sentences in U.S. prisons, including nearly three thousand in Washington state. A University of Washington study from 2015 estimates that nearly 1,400 of those are serving life without the possibility of parole—either because, like Steen, they were handed that sentence from a judge, or because their cases don’t fall under the purview of the ISRB and they have sentences of 39 years or more. Research shows life expectancy in prison to be lower than that of the average population, so four or more decades is also very likely to mean life, in the literal sense.

And whereas the racial disparities in the regular prison population are stark, they are even more so for those serving life sentences. African Americans make up 4.1 percent of the population in Washington, and 18.4 percent of its prison inmates—but a full 28 percent of those serving life without parole.

“It’s appalling,” says Gerald Hankerson, president of the Seattle/King County NAACP and a former lifer, who received clemency from Governor Christine Gregoire in 2009. “Everyone knows something has to change,” but lawmakers consistently “trim around the edges rather than going directly at the heart of the problem.” As one DOC staffer testified during a House Public Safety Committee meeting this January, over the past 12 years, the legislature has made approximately 370 separate changes to the Revised Codes of Washington that define felony sentencing. None have touched parole.

This conversation has surfaced and resurfaced many times in Washington state, including during the 2014 legislative session. But once again a bill has been introduced in Olympia that would give most long-term prisoners a chance at freedom. HB 1789 would create, for the first time since 1984, an avenue for release for most of Washington’s long-term inmates after 20 years of confinement. The bill, drafted by Hankerson and supported by members of the Washington Community Action Network (Washington CAN), would establish, instead of a parole board, a “community review board” consisting of community leaders, faith leaders, and behavioral health professionals as well as prosecutors and law enforcement.

Yet it is unlikely that the bill will move very far. As of press time, it has been amended to include only the section that calls for an independent review of the state’s sentencing laws and practices—something that Representative Roger Goodman (D-Kirkland), chair of the House Public Safety Committee, says “is long overdue.” As for the rest of the bill, he told his colleagues, “I don’t know if we would have the support for that.”

Dan Satterberg agrees. The district attorney has served on the state’s Sentencing Guidelines Commission and has been vocal in recent years about the need for reform, particularly for those inmates with a string of nonviolent offenses. But politically speaking, to this day, looking “soft on crime” makes lawmakers balk. “It’s a steep hill to climb,” he says.

Yes, lawmakers are often “worried about ‘soft on crime,’ ” says Hankerson, exasperated. “Whatever. Get over it. That argument is stale. That is a stale argument.”

Though their fates are, at this point, the same, every lifer in Washington state has a different story of the time before. Steen’s came to an end on June 2, 2008, shortly after he slipped into a small bank in SoDo, strode up to the teller, tapped the bulletproof glass with a .22 handgun, and said, “Give me the money.” That was a departure from his previous MO, which had been to silently hand the teller a note with the scrawl “This is a robbery—give me the money” or “This is a robbery—large cash quickly.” It was also the first time he’d ever brought a gun.

Steen says he’d gotten himself into a self-destructive kind of darkness, fueled by hard drugs and self-loathing. He holed up sleeplessly in a motel for a few weeks that May, popping in and out only to hand robbery note after robbery note to bank tellers. All those robberies were being blasted on the evening news; “I couldn’t even go into an AMPM without a little kid going, ‘Daddy, he looks familiar.’ ” And so, feeling crazed and paranoid, he bought a gun—not so much to facilitate the robbery, he insists, as to “[protect] myself against the people I thought were after me.”

At the time, according to court documents, he told detectives simply that “he was ‘hot,’ he wanted to do something different, and he wanted more money.”

Steen had spent most of the previous decade in and out of prison for bank robberies and thefts—demanding a few hundred or thousand dollars from a bank teller, stealing leather jackets from Nordstrom, pawning $250 worth of electronics and clothing that he stole from a friend. He was convicted twice of second-degree robbery—first of a clothing store in 1992, then of a string of banks in 1996. He also has one cocaine possession charge, and one charge from 2008 for violating a restraining order that a former partner had filed against him, saying he’d repeatedly punched and choked her, although by the end of that year charges had been dropped.

He spent the money on drugs, but also cars and clothes and gifts for friends. He’d get a good job—including an early one doing wire transfers at a bank, no less—but then would be pulled out of it by a sudden whim, a sudden paycheck. He had two daughters with two different mothers by age 21, and the pressure of having to support them, along with the clutch of addiction and its piercing shame, unraveled him bit by bit. “This crazy habit that I had, I felt like I couldn’t get any help for, because it was just year after year after year since 1986 that this thing would just wait until I had come up to a certain point, then it would just jump out of my skin and just tear it all down,” he says.

So maybe it was the drugs that day on June 2; maybe it wasn’t. Steen told detectives at the time that he was not under the influence of any drugs or alcohol.

He does remember details, which don’t differ much from those in King County Superior Court documents. After leaving the bank in SoDo, he tore off in a silver Mitsubishi Eclipse, the police hot on his heels. It was his fifth bank robbery in a little over two weeks. In a panic, Steen squealed from I-5 to I-90 East, then off the freeway into a residential neighborhood on Mercer Island. He was swiftly cornered on a dead-end street, caught between a blaring police car and Lake Washington; he ignored the officers with guns drawn and rammed his car straight into the police car. They fired. One bullet hit Steen in the hand as he clutched the steering wheel, ultimately costing him his right index finger.

“I didn’t even know that they were shooting until I was shot,” he recalls. “Easily, one of those bullets could’ve went through my head. I don’t really know how to describe it. I read police reports on that. And even the detectives, they were wanting to know, ‘Did you want to die?’ It wasn’t even the thought of that. It was almost like I wasn’t even driving. Someone else was.”

There’s a pause. “Sometimes it feels like I left a lot there that day on Mercer Island.”

After two hours of deliberation, in July 2009 a jury found Steen guilty as charged of five counts of first-degree robbery, plus 60 months for carrying a firearm.

The average length of stay in prison in Washington state for a first-degree robbery, without prior convictions, is three years. But under the Persistent Offender Accountability Act, or “three strikes” law—passed as a citizens’ initiative in 1993—Steen would serve a much longer sentence. Taking into account the two different convictions for second-degree robbery, each count of first-degree robbery from the 2008 spree put him away for life.

Greg Steen, therefore, is now serving five life sentences plus 60 months.

“There wasn’t a sense of panic” or anger when he got the sentence, though, he says. He’d been living with two strikes for years. He knew, in a sense, that this could be coming. Instead, in that moment, “everything is starting to make sense to me.” First off, “There is nothing I can do about where I’m going. I can play crazy, I can kick and scream all I want. These people don’t give a damn.” Instead, “How strong do I stand up in that court room? Take responsibility for my actions? Admit that I was wrong for what I did?… It was me. I did that. It was my fault. I was wrong for doing that. Let me see what I can do with my life now.”

He does not believe, however, that he should be locked up for the entirety of it.

In 2014, after serving five years of his sentence, Steen became active in the criminal-justice reform efforts of the Black Prisoner’s Caucus, an education, advocacy, and support group begun at Monroe Correctional Complex in 1972. When the caucus began drafting legislation over the past year, calling for the creation of a community review board for those serving life without parole, he offered feedback. He had become a part of a longstanding effort, helping build on a concept that has existed for some time; Hankerson says that the community review board was part of a bill that he drafted back in 2000, while in prison.

When the BPC and Washington CAN and other groups came together to work on the bill that would become HB 1789, the review board was a central tenet. But the groups did not see eye-to-eye on every matter: Disagreements arose over organizing strategy, and in particular the idea that some crimes are too egregious to qualify.

In sentencing reform, a line is often drawn between “violent” and “nonviolent” offenders. It’s easier for lawmakers, violent-crime victims, and the public to sympathize with someone like Steen who did not take a life. That’s why those with aggravated first-degree murder and sex-offense convictions would not be eligible under HB 1789—and that in turn is why the bill does not have the support of the Black Prisoners’ Caucus as a body, because among the group’s priorities for legislation like this is that it include every crime, every charge.

“The number-one thing that happens when you get down to Olympia,” says Senait Brown—an antiracist organizer who has worked extensively with the BPC and founder of Black Out Washington, a group formed in part to advocate for sentencing reform—“is they wanna separate quote-unquote ‘violent’ criminals. And there’s so many different circumstances that can lead to those labels. And there’s so much divisiveness that that causes—even in prison. So our non-negotiable is that we do not agree that we should separate out or exclude anything. There is no such thing as incremental steps on this.”

Gerald Hankerson is sympathetic. He says he knows that while targeting nonviolent offenders is “politically safe,” he believes that the people at the lowest risk to reoffend are often the “violent” offenders politicians fear. In general, research shows that paroled lifers do indeed have a minuscule recidivism rate; one study of parolees in California who’d been convicted of murder and sentenced to life found that less than one percent committed other crimes once paroled. And recidivism rates in general drop precipitously when the person released is over 50, regardless of the crime he or she was originally convicted of. (To that end, another bill proposed this legislative session would provide a path for release through the existing ISRB for older offenders. That bill, too, hasn’t moved much.)

Still, Hankerson is clear in his belief that the only chance a bill like HB 1789 has is if high-level violent offenses are left out. The bill has little chance as is, but the inclusion of aggravated first-degree murder would have been “the poisonous pill,” he says, that would have erased the sympathies of lawmakers on the fence.

The political status quo is easy to maintain; again, “nobody wants to be labeled particularly ‘soft on crime,’ ” says Jon Zulauf, president of the Seattle Clemency Project, a nonprofit he founded in January 2016 to help lifers find pro bono lawyers to assist them with their clemency petitions. “All you have to do is focus people’s attention on the crime and how badly [the inmate] hurt people … and a good percentage of the public would say, ‘Are we kidding? Why in the world are we gonna release that guy?’ ”

Dan Clements, for example, lost his 21-year-old son to a brutal murder in 2006; as he testified at HB 1789’s hearing earlier this month, his son “bled out in a flower bed” while his high-school friends stood by, helpless. “This bill is a frontal assault on victims’ rights,” Clements said.

Lew Cox, executive director of Violent Crime Victim Services, a Tacoma-based group he formed after suffering through the aftermath of his daughter’s murder, agrees. “What about us victims? We get a life sentence,” he says. Families of the incarcerated visit their sons and brothers and spouses in prison; “I have to go visit my daughter at her grave.”

Cox has spent time both advocating for victims’ families and doing prison ministry at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, and he believes that “the length of time in prison does not calculate to rehabilitation.” Inmates are in a controlled environment, he says. “Murderers and psychopaths are compliant in prison. Recidivism is calculated when they’re released.” Added Clements, during his testimony: “Model prisoners do not necessarily make model citizens.”

Yet others—on both sides of prison walls—maintain that lifers are the inmates they admire. Hankerson, Steen, and Zulauf say these are people who’ve spent decades maturing, coming to terms with themselves, thinking about how they got to where they are and how to help others avoid going down that same path. “If you have a lifer who’s trying to improve himself,” says Steen, “that’s the dude you need to watch. That’s the one who’s gonna be somebody someday.”

Regardless of their crimes, lifers who have been in for decades “are very different people than the 20-year-old who got into trouble,” says Zulauf.

According to Ginny Parham, a Tacoma resident and volunteer with Washington CAN, her son, Willie, is one of those people. He was handed a 96-year sentence when he was 18 for a gang-related drive-by shooting resulting in a death. He’s now 38, a lifer at Clallam Bay. “There’s no motive for hope and rehabilitation” in the current system, says Parham. Inmates are “just stacked, packed, warehoused.” But Willie teaches math and history classes, is getting an associate’s degree, and mentors at-risk youth; “He looks for every opportunity to better himself,” she says. She acknowledges his responsibility for others’ suffering, testifying at the HB 1789 hearing that “I had to sit in that courtroom; it was the horriblest thing I ever had to go through to witness that victim’s family.” Still, she maintains Willie has changed dramatically in the past two decades. If inmates are “achieving and achieving and achieving,” she argues, “then give them a chance to sit in front of a parole board and plead their case.”

Joy Nash, also with Washington CAN, says her son, James, has “matured so much” since he entered prison in 1996 on a first-degree murder charge, also for a drive-by shooting. He was 20 at the time, and has more than 20 years left to go on his sentence. It’s been more than two decades, but she chokes up when she speaks about him—especially about the experience of visiting him in prison, then having to leave him there. She was nearly barred from his visitation list toward the beginning, she says, because she was crying too much, making too much of a scene. “I couldn’t handle it emotionally. I need my son home,” she says, her voice strained and thick with tears. “My children need their sibling home. His daughter needs him home. His nieces and nephews need him home. The community needs him home, because he’s made ardent strides to change. I’m so proud of the man he’s become.”

Zulauf says he has met many, many lifers through his work, and says “Many of these guys are bright, they’re self-educated, mature, thoughtful people… . My feeling is that it’s a waste of these people’s lives, number one. Number two, society isn’t getting much out of this. Number three, it’s expensive.” Washington state spends roughly $46,000 per inmate per year—and more for aging offenders, as health-care costs increase.

“I understand that there are some crimes that are so extreme that maybe somebody should have no chance of getting out,” says Jennifer Smith, co-executive director of the Seattle Clemency Project, who, like Zulauf, has spoken with many lifers who she believes are thoughtful and transformed. “But I don’t believe that it’s humane. I think it’s on the level of a human-rights issue to incarcerate people for the rest of their life.”

Tom McBride, executive secretary of the Washington Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, says that while a big part of long sentences is “just deserts”—pure punishment for a horrific thing someone has done, which has nothing to do with public safety or the risk of recidivism—he and many prosecutors “see the value in rehabilitation and second chances” and that “a means to be released for someone who has turned things around… should exist.” His argument: It already does. The Clemency & Pardons Board functions well, he says. Especially in the past five or six years, a growing number of people have been fairly evaluated and released that way, he says, adding that it would be a better idea to consider expanding that board rather than duplicating its efforts.

Among many reformers, however, clemency is often pegged as too limited and too political; a governor could ruin his or her career by releasing an offender who commits another crime. And even the Board itself, staffed by volunteers, is legally instructed to recommend a pardon only in “extraordinary circumstances.” Another, more independent and comprehensive review board is necessary, they argue, to give lifers something to live for. And that board should not be run by the Department of Corrections or staffed only by legal and law-enforcement experts, Hankerson says. It should be a “community” review board because “who best capable to determine who comes back to the community, than the community itself?”

“My two older brothers were in gangs,” says a black man named Marcus, speaking in a video that community members made as part of the effort to pass HB 1789. “The easiest thing for me to do was to follow in their footsteps. The hardest thing for me to do was to do something different with my life. At 13 years old, I found myself selling drugs; by 14, I was heavily involved in gang activity … I spent all of my adolescent years in jails, group homes, and institutions.” By 19 he had received a life sentence for a gang-related shooting.

Senait Brown and other organizers believe that creating a holistic, forward-thinking community review board could recognize that “there’s systemic trauma that happens to people,” particularly people of color. “It’s not just a broken individual we’re reviewing.”

The numbers are sobering. One ACLU analysis of U.S. Sentencing Commission and state Departments of Corrections data, for instance, found that African Americans make up 65.4 percent of prisoners serving life-without-parole sentences for nonviolent offenses. Many people spend years and years behind bars for drug possession alone; in 2014, nearly half of all people sentenced for drug possession were black or Hispanic. While crack was devastating low-income communities of color in the 1980s and ’90s, criminal-justice systems across the country responded by leveraging far harsher mandatory minimums for crack than for powdered cocaine. And no matter the crime, incarceration has been impacting black communities in particular for decades. One in nine black children in the U.S. has an incarcerated parent.

“If you can’t take a racial lens on your analysis of institutional policies, then you are in denial,” Layne Pavey says. “Until we do that, we’re not actually going to have solutions for what is actually causing what we call ‘crime.’ ”

Joy Nash mentions, almost in passing, that the work she’s doing right now to pass HB 1789 is not only for her son. “I have a grandson that’s in. I have a nephew that’s in. My ex-brother-in-law died in the same prison that my son is in.” And she wonders what could have happened had James not been convicted. “The rate he was going… he’d been shot twice before he was sent down. In a way, maybe this was the best thing that could have happened to him… it’s like a catch-22. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

This is “a bigger story than just one person,” argues Brown. While the short-term goal for the Black Prisoners’ Caucus and all its allies, she says, is to pass legislation that would “get folks free, the long-term goal is to get us free.”

In the meantime, prisoners like Greg Steen must live with the knowledge that they may never get out. HB 1789 has been reduced to a conversation, and after a final hearing on Wednesday, that conversation may get bumped to next year, and the year after that. There’s always the possibility of clemency, but barring that, for thousands of people a life in the custody of the Department of Corrections stretches out in a long, pale-beige line, ringed by spools of razor wire.

Steen nevertheless refuses to lie down and give up. “If you want to change, you can change. No matter what,” he says. “I was never really wont to be consumed, like, ‘It’s over, forget about it, it’s over,’ ” even—and especially—when he was sentenced to life without parole. “It’s not over. And I feel like standing up right now, and so that’s what I’m gonna do.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com